Transfer of Japanese Culture Patterns on the Example of a Comic Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

Birthdays Susan Cole

Volume 29 Number 4 Issue 346 September 2016 A WORD FROM THE EDITOR Kimber Groman (graphic artist) and others August was Worldcon in Kansas City. MidAmericon 2 $25 for 3 days pre con, $30 at the door had a lot going on. There were two Hugo Ceremonies. There spacecoastcomiccon.com were a lot of exhibits and of course 5,000 items on the program. I did a lot of work pre-con and got to see aKansas City at the Animate! Florida same time. The con was great and I need to start working on my September 16-19 report. Port St Lucie Civic Center This month I may checkout some local events. I may try 9221 SE Civiv Center Place to squeeze in a review. Port St Lucie FL As always I am willing to take submissions. Guests: Tony Oliver (Rick Hunter, Robotech) See you next month. Julie Dolan (Star Wars: Rebels) Erica Mendez (Ryoka Matoi, Kill La Kill) Events and many more $55 for 3 days pre con Comic Book Connection animateflorida.com/ September 3-4 Holiday Inn Treasure Comic Con 2300 SR 16 September 16-19 ST Augustine, FL 32084 Greater Fort Lauderdale Convention Center $5 at the door 1950 Eisenhower Blvd, thecomicbookconnection.com Fort Lauderdale, FL 33316 Guests: Space Coast Comic Con Billy West (Phil Fry, Futurama) September 9-11 Kristin Bauer (Maleficient, Once Upon a Space Coast Convention Center Time) 301 Tucker Ln Beverly Elliot(Granny, Once Upon a Time) Cocoa, FL 32926 and many more Guests: Terance Baker (comic artist) $35 for 3 days pre con, $40 at the door Jake Estrada (comic artist) www.treasurecoastcomiccon.com Fusion Con II September 17 Birthdays New Port Richey Recreation & Aquatic Center 6630 Van Buren St Susan Cole - Sept. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

16-18 October 2019 Shanghai New International Expo Center Message from CTJPA President

Visitor Guide E6 16-18 October 2019 Shanghai New International Expo Center Message from CTJPA President Dear participants, On behalf of China Toy & Juvenile Products Association (CTJPA), the organizer of China Toy Expo (CTE), China Kids Expo (CKE), China Preschool Expo (CPE) and China Licensing Expo (CLE), I would like to extend our warmest welcome to all of you and express our sincere thanks for all your support. Launched in 2002, the grand event has been the preferred platform for leading brands from around the world to present their newest products and innovations, connect with customers and acquire new sales leads. In 2019, the show will feature 2,508 global exhibitors, 4,859 worldwide brands, 100,000 professional visitors from 134 countries and regions, showcasing the latest products and most creative designs in 230,000 m² exhibition space. It is not only a platform to boost trade between thousands of Chinese suppliers and international buyers, but also an efficient gateway for international brands to tap into the Chinese market and benefit from the huge market potential. CTJPA has designed the fair as a stage to show how upgraded made-in-China will influence the global market and present worldwide innovative designs and advanced technologies in products. Moreover, above 1800 most influential domestic and international IPs will converge at this grand event to empower the licensing industry. IP owners are offered opportunities to meet with consumer goods manufacturers, agents and licensees from multi-industries to promote brands and expand licensing business in China and even Asia. Whether you are looking to spot trends, build partnerships, or secure brand rights for your products, we have the answer. -

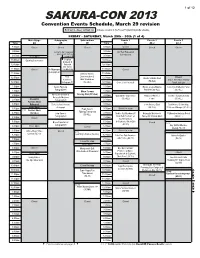

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

Archiving Movements: Short Essays on Materials of Anime and Visual Media V.1

Contents Exhibiting Anime: Archive, Public Display, and the Re-narration of Media History Gan Sheuo Hui ………… 2 Utilizing the Intermediate Materials of Anime: Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise Ishida Minori ………… 17 The Film through the Archive and the Archive through the Film: History, Technology and Progress in Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise Dario Lolli ………… 25 Interview with Yamaga Hiroyuki, Director of Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise What Do Archived Materials Tell Us about Anime? Kim Joon Yang ………… 31 Exhibiting Manga: Impulses to Gain from the Archiving/Unearthing Anime Project Jaqueline Berndt ………… 36 Analyzing “Regional Communities” with “Visual Media” and “Materials” Harada Ken’ichi ………… 41 About the Archive Center for Anime Studies in Niigata University ………… 45 Exhibiting Anime: Archive, Public Display, and the Re-narration of Media History Gan Sheuo Hui presumably, the majority are in various storage Background of the Project places after their production cycles. It is not The exhibition “A World is Born: The uncommon that they are forgotten, displaced or Emerging Arts and Designs in 1980s Japanese eventually discarded due to the expenses incurred Animation” (19-31 March 2018) hosted at DECK, for storage. In many ways, these materials an independent art space in Singapore, is encompass an often forgotten yet significant part of an ongoing research collaboration research resource essential for understanding between the researchers from Puttnam School key aspects of Japanese animation production of Film and Animation in Singapore and the cultures and practices. Archive Center for Anime Studies in Niigata “A World is Born” was an exhibition focusing University (ACASiN). -

Manga Japanese Gay-Themed by Mark Mclelland YAOI in Italian Translation

Manga Japanese gay-themed by Mark McLelland YAOI in Italian translation. Photograph by Giovanni dal Orto. Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. The image appears Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. under the Creative Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Commons Attribution Share-Alike License. In Japan, manga--or comic books--have, for more than four decades, been an important medium of cultural expression; more than one billion are sold every year, including titles dedicated to food, travel, sports, business, education, and, of course, sex. Men's manga are notorious in the west for their rorikon ("Lolita Complex") stories featuring sexualized and at times violent representations of girls; but women's manga, too, feature a wide range of sexual situations. A genre of erotic manga known as "ladies comics," created by women artists such as Milk Morizono, sometimes feature male and female homosexuality, pedophilia, scatology and B&D/S&M. However, the most widespread representations of homosexuality occur in a genre of women's comics known as "boy love" (shonen'ai) featuring romantic stories about "beautiful boys" (bishonen). One pioneer of this style in the early 1970s was Moto Hagio, whose November Gymnasium (1971) and Thomas' Heart (1974) featured tragic love triangles set in private schools at the beginning of the last century. Other famous titles also include cross-dressed heroines, such as Riyoko Ikeda's The Rose of Versailles (1972). Set at the time of the French Revolution, the story features both homoerotic and heterosexual encounters and was later staged as a popular musical by the all-female Takarazuka revue. The early tales were long and beautifully crafted, and the sex--although hinted at--was rather demurely pictured. -

Graphic Novels: Enticing Teenagers Into the Library

School of Media, Culture and Creative Arts Department of Information Studies Graphic Novels: Enticing Teenagers into the Library Clare Snowball This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University of Technology March 2011 Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgement has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: _____________________________ Date: _________________________________ Page i Abstract This thesis investigates the inclusion of graphic novels in library collections and whether the format encourages teenagers to use libraries and read in their free time. Graphic novels are bound paperback or hardcover works in comic-book form and cover the full range of fiction genres, manga (Japanese comics), and also nonfiction. Teenagers are believed to read less in their free time than their younger counterparts. The importance of recreational reading necessitates methods to encourage teenagers to enjoy reading and undertake the pastime. Graphic novels have been discussed as a popular format among teenagers. As with reading, library use among teenagers declines as they age from childhood. The combination of graphic novel collections in school and public libraries may be a solution to both these dilemmas. Teenagers’ views were explored through focus groups to determine their attitudes toward reading, libraries and their use of libraries; their opinions on reading for school, including reading for English classes and gathering information for school assignments; and their liking for different reading materials, including graphic novels. -

S19-Seven-Seas.Pdf

19S Macm Seven Seas Nurse Hitomi's Monster Infirmary Vol. 9 by Shake-O The monster nurse will see you now! Welcome to the nurse's office! School Nurse Hitomi is more than happy to help you with any health concerns you might have. Whether you're dealing with growing pains or shrinking spurts, body parts that won't stay attached, or a pesky invisibility problem, Nurse Hitomi can provide a fresh look at the problem with her giant, all-seeing eye. So come on in! The nurse is ready to see you! Author Bio Shake-O is a Japanese artist best known as the creator of Nurse Hitomi's Monster Infirmary Seven Seas On Sale: Jun 18/19 5 x 7.12 • 180 pages 9781642750980 • $15.99 • pb Comics & Graphic Novels / Manga / Fantasy • Ages 16 years and up Series: Nurse Hitomi's Monster Infirmary Notes Promotion • Page 1/ 19S Macm Seven Seas Servamp Vol. 12 by Strike Tanaka T he unique vampire action-drama continues! When a stray black cat named Kuro crosses Mahiru Shirota's path, the high school freshman's life will never be the same again. Kuro is, in fact, no ordinary feline, but a servamp: a servant vampire. While Mahiru's personal philosophy is one of nonintervention, he soon becomes embroiled in an ancient, altogether surreal conflict between vampires and humans. Author Bio Strike Tanaka is best known as the creator of Servamp and has contributed to the Kagerou Daze comic anthology. Seven Seas On Sale: May 28/19 5 x 7.12 • 180 pages 9781626927278 • $15.99 • pb Comics & Graphic Novels / Manga / Fantasy • Ages 13 years and up Series: Servamp Notes Promotion • Page 2/ 19S Macm Seven Seas Satan's Secretary Vol. -

Sailor Mars Meet Maroku

sailor mars meet maroku By GIRNESS Submitted: August 11, 2005 Updated: August 11, 2005 sailor mars and maroku meet during a battle then fall in love they start to go futher and futher into their relationship boy will sango be mad when she comes back =:) hope you like it Provided by Fanart Central. http://www.fanart-central.net/stories/user/GIRNESS/18890/sailor-mars-meet-maroku Chapter 1 - sango leaves 2 Chapter 2 - sango leaves 15 1 - sango leaves Fanart Central A.whitelink { COLOR: #0000ff}A.whitelink:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.whitelink:visited { COLOR: #0000ff}A.BoxTitleLink { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:hover { COLOR: #465584; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:visited { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.normal { COLOR: blue}A.normal:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.normal:visited { COLOR: #000020}A { COLOR: #0000dd}A:hover { COLOR: #cc0000}A:visited { COLOR: #000020}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper { COLOR: #ff0000}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:hover { COLOR: #ffaaaa}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:visited { COLOR: #cc0000}.BoxTitleColor { COLOR: #000000} picture name Description Keywords All Anime/Manga (0)Books (258)Cartoons (428)Comics (555)Fantasy (474)Furries (0)Games (64)Misc (176)Movies (435)Original (0)Paintings (197)Real People (752)Tutorials (0)TV (169) Add Story Title: Description: Keywords: Category: Anime/Manga +.hack // Legend of Twilight's Bracelet +Aura +Balmung +Crossovers +Hotaru +Komiyan III +Mireille +Original .hack Characters +Reina +Reki +Shugo +.hack // Sign +Mimiru -

Graphic Novels Plan

Automatically Yours™ from Baker & Taylor Automatically Yours™ Graphic Novels Plan utomatically YoursTM from Baker & Taylor is a Specialized Collection Program that delivers the latest publications from popular authors right to Ayour door, automatically. Automatically Yours offers a variety of plans to meet your library’s needs including: Popular Adult Fiction Authors, B&T Kids, Spokenword Audio, Popular Book Clubs and Graphic Novels. Our Graphic Novels Plan delivers the latest publications to your library, automatically. Choose the novels that are right for your library and we’ll do the rest. No more placing separate orders, no worrying about title availability - they’ll arrive on time at your library. A new feature of the Automatically Yours program is updated lists of forthcoming titles available on our website, www.btol.com. Click on the Public Tab, then choose Automatic Shipments and Automatically Yours to view the current lists. Sign-up today! Simply fill out the enclosed listing by indicating the number of copies you require, complete the Account Information Form and return them both to Baker & Taylor. It’s that simple! Questions? Call us at 800.775.1200 x2315 or visit www.btol.com Automatically Yours™ from Baker & Taylor Sign up by Vendor/Character, Author or Illustrator. Fill in the quantity you need for each selection, fill out the Account Information Form and we’ll do the rest. It’s that simple! * Vendor/Character Listing: AIT-Planet Lar: ____ Hellboy - Adult Fantagraphics: ____ ALL Titles - Teen ____ Lone Wolf and Cub - Adult ____ ALL Hardcover Titles - Adult ____ O My Goddess - All Ages ____ ALL Paperback Titles - Adult Alternative Comics: ____ Predator - Teen ____ ALL Titles - Adult G.T.