Mass-Marketing Fraud: a Threat Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity Theft Literature Review

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Identity Theft Literature Review Author(s): Graeme R. Newman, Megan M. McNally Document No.: 210459 Date Received: July 2005 Award Number: 2005-TO-008 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. IDENTITY THEFT LITERATURE REVIEW Prepared for presentation and discussion at the National Institute of Justice Focus Group Meeting to develop a research agenda to identify the most effective avenues of research that will impact on prevention, harm reduction and enforcement January 27-28, 2005 Graeme R. Newman School of Criminal Justice, University at Albany Megan M. McNally School of Criminal Justice, Rutgers University, Newark This project was supported by Contract #2005-TO-008 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Toolkit for March Fraud Prevention Month 2018 Middle Agers

Toolkit for March Fraud Prevention Month 2018 Middle Agers FRAUD: Recognize. Reject. Report. Table of Contents Introduction ‐‐‐ 3 RCMP Videos ‐‐‐ 4 OPP Fraud Prevention Videos ‐‐‐ 4 Competition Bureau Fraud Prevention Videos ‐‐‐ 4 CAFC Logo ‐‐‐ 4 Calendar of Events ‐ Facebook and Twitter ‐‐‐ 5 Statistics ‐‐‐ 6 Theme 3: Scams Targeting Middle Agers ‐‐‐ 7 Service ‐‐‐ 7 Extortion ‐‐‐ 7 Personal Information ‐‐‐ 8 Loan ‐‐‐ 8 Investment ‐‐‐ 9 Text Message ‐‐‐ 10 2 Introduction In preparation for March Fraud Prevention Month, the Canadian Anti‐Fraud Centre (CAFC) has compiled a toolkit specifically designed for middle aged Canadians to further raise awareness and help prevent victimization. We encourage all partnering organizations to use the CAFC logo, contact points and resource materials in this toolkit on their website, in print and on their social media platforms. The CAFC will actively be posting on Facebook and Twitter daily (#FPM2018, #MPF2018) and participating in the fraud chats: Use the following hashtag – #fraudchat – to join. The CAFC is Canada’s central repository for data, intelligence and resource material as it relates to mass marketing fraud and identity fraud. Victims who report to the CAFC are also encouraged to report directly to their local police. The CAFC does not conduct investigations but provides valuable assistance to law enforcement agencies all over the world by identifying connections among seemingly unrelated cases. Your information may provide the piece that completes the puzzle. The CAFC is a support agency to law enforcement. Middle Aged consumers can report directly to the CAFC by calling toll free 1‐888‐495‐8501 or online through the CAFC Online Fraud Reporting System (FRS). -

Young Adults 2021-02-15

2021 Fraud Prevention Toolkit – Young Adults 2021-02-15 YOUNG ADULTS 2021 Fraud Prevention Toolkit Table of Contents Introduction --- 3 RCMP Videos --- 4 OPP Videos --- 4 Competition Bureau of Canada Videos --- 4 CAFC Fraud Prevention Video Playlists --- 4 CAFC Logo --- 4 Calendar of Events --- 5 About the CAFC --- 7 Statistics --- 7 Reporting Fraud --- 8 Most Common Frauds Targeting Young Adults --- 8 • Identity Theft & Fraud --- 9 • Extortion --- 10 • Investments --- 11 • Job --- 12 • Merchandise --- 13 Young Adults 2 Introduction As fraud rates continue to increase in Canada, the world is going through a global pandemic. The COVID-19 has created an environment that is ripe for fraud and online criminal activity. The COVID-19 has resulted in never-before-seen numbers of people turning to the internet for their groceries, everyday shopping, banking and companionship. Coupled with the profound social, psychological and emotional impacts of COVID-19 on people, one could argue that the pool of potential victims has increased dramatically. March is Fraud Prevention Month. This year’s efforts will focus on the Digital Economy of Scams and Frauds. The Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (CAFC) has compiled a toolkit specifically designed for young adult Canadians (born 1987-2005) to further raise public awareness and prevent victimization. We encourage all our partner to use the resources in this toolkit on their website, in print and on their social media platforms. Throughout the year, the CAFC will be using the #kNOwfraud and #ShowmetheFRAUD descriptors to link fraud prevention messaging. We will also continue to use the slogan “Fraud: Recognize, Reject, Report”. During Fraud Prevention Month, the CAFC will post daily on its Facebook and Twitter platforms (#FPM2021). -

Effect of Pyramid Schemes to the Economy of the Country - Case of Tanzania

International Journal of Humanities and Management Sciences (IJHMS) Volume 5, Issue 1 (2017) ISSN 2320–4044 (Online) Effect of pyramid schemes to the Economy of the Country - Case of Tanzania Theobald Francis Kipilimba come up with appropriate laws and mechanisms that will stop Abstract— Pyramid scheme, in their various forms, are not a those unscrupulous people praying on unsuspecting new thing in the world, however, they have reared their ugly individuals. Help supervisory institutions formulate menacing heads‘ in the Tanzanians society only recently. Before the appropriate policies that will require all investment plans to Development entrepreneurship Community Initiative (DECI) debacle be documented, filed and thoroughly scrutinized and come up other schemes such as Women Empowering, woman had already with the ways to recover assets of the culprits and use them to racked havoc in the society.This study intended to evaluate the extent compensate the victims of get rich quick schemes. to which Tanzanians knew about the pyramid schemes operating in the world, their participation in these schemes and their general feelings towards the scammers, our judicial system and the course II. BASIC VIEW OF PYRAMID SCHEME action they are likely to take in the event they are scammed. Results Pyramid scheme is a fraudulent moneymaking scheme in show that most Tanzanians are very naïve when it comes to pyramid which people are recruited to make payments to others above schemes, with very scant knowledge about these schemes. Many do them in a hierocracy while expecting to receive payments not know if they have participated in these schemes but in those instances that they had, they suffered huge financial losses. -

The Economics of Cryptocurrency Pump and Dump Schemes

The Economics of Cryptocurrency Pump and Dump Schemes JT Hamrick, Farhang Rouhi, Arghya Mukherjee, Amir Feder, Neil Gandal, Tyler Moore, and Marie Vasek∗ Abstract The surge of interest in cryptocurrencies has been accompanied by a pro- liferation of fraud. This paper examines pump and dump schemes. The recent explosion of nearly 2,000 cryptocurrencies in an unregulated environment has expanded the scope for abuse. We quantify the scope of cryptocurrency pump and dump on Discord and Telegram, two popular group-messaging platforms. We joined all relevant Telegram and Discord groups/channels and identified nearly 5,000 different pumps. Our findings provide the first measure of the scope of pumps and suggest that this phenomenon is widespread and prices often rise significantly. We also examine which factors affect the pump's \suc- cess." 1 Introduction As mainstream finance invests in cryptocurrency assets and as some countries take steps toward legalizing bitcoin as a payment system, it is important to understand how susceptible cryptocurrency markets are to manipulation. This is especially true since cryptocurrency assets are no longer a niche market. The market capitaliza- tion of all cryptocurrencies exceeded $800 Billion at the end of 2017. Even after the huge fall in valuations, the market capitalization of these assets is currently around $140 Billion. This valuation is greater than the fifth largest U.S. commer- cial bank/commercial bank holding company in 2018, Morgan Stanley, which has a market capitalization of approximately $100 Billion.1 In this paper, we examine a particular type of price manipulation: the \pump and dump" scheme. These schemes inflate the price of an asset temporarily so a ∗Hamrick: University of Tulsa, [email protected]. -

North East Multi-Regional Training Instructors Library

North East Multi-Regional Training Instructors Library 355 Smoke Tree Business Park j North Aurora, IL 60542-1723 (630) 896-8860, x 108 j Fax (630) 896-4422 j WWW.NEMRT.COM j [email protected] The North East Multi-Regional Training Instructors Library In-Service Training Tape collection are available for loan to sworn law enforcement agencies in Illinois. Out-of-state law enforcement agencies may contact the Instructors Library about the possibility of arranging a loan. How to Borrow North East Multi-Regional Training In-Service Training Tapes How to Borrow Tapes: Call, write, or Fax NEMRT's librarian (that's Sarah Cole). Calling is probably the most effective way to contact her, because you can get immediate feedback on what tapes are available. In order to insure that borrowers are authorized through their law enforcement agency to borrow videos, please submit the initial lending request on agency letterhead (not a fax cover sheet or internal memo form). Also provide the name of the department’s training officer. If a requested tape is in the library at the time of the request, it will be sent to the borrower’s agency immediately. If the tape is not in, the borrower's name will be put on the tape's waiting list, and it will be sent as soon as possible. The due date--the date by which the tape must be back at NEMRT--is indicated on the loan receipt included with each loan. Since a lot of the tapes have long waiting lists, prompt return is appreciated not only by the Instructors' Library, but the other departments using the video collection. -

National Trading Standards – Scams Team Review

EUROPE National Trading Standards – Scams Team Review Jeremy Lonsdale, Daniel Schweppenstedde, Lucy Strang, Martin Stepanek, Kate Stewart For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1510 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif., and Cambridge, UK R® is a registered trademark. © Copyright 2016 National Trading Standards RAND Europe is an independent, not-for-profit policy research organisation that aims to improve policy and decisionmaking in the public interest through research and analysis. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the sponsor. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org www.rand.org/randeurope Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................... 3 Preface .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 7 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

The Underground Economy.Pdf

THE THE The seeds of cybercrime grow in the anonymized depths of the dark web – underground websites where the criminally minded meet to traffic in illegal products and services, develop contacts for jobs and commerce, and even socialize with friends. To better understand how cybercriminals operate today and what they might do in the future, Trustwave SpiderLabs researchers maintain a presence in some of the more prominent recesses of the online criminal underground. There, the team takes advantage of the very anonymity that makes the dark web unique, which allows them to discretely observe the habits of cyber swindlers. Some of the information the team has gathered revolves around the dark web’s intricate code of honor, reputation systems, job market, and techniques used by cybercriminals to hide their tracks from law enforcement. We’ve previously highlighted these findings in an extensive three-part series featured on the Trustwave SpiderLabs blog. But we’ve decided to consolidate and package this information in an informative e-book that gleans the most important information from that series, illustrating how the online criminal underground works. Knowledge is power in cybersecurity, and this serves as a weapon in the fight against cybercrime. THE Where Criminals Congregate Much like your everyday social individual, cyber swindlers convene on online forums and discussion platforms tailored to their interests. Most of the criminal activity conducted occurs on the dark web, a network of anonymized websites that uses services such as Tor to disguise the locations of servers and mask the identities of site operators and visitors. The most popular destination is the now-defunct Silk Road, which operated from 2011 until the arrest of its founder, Ross Ulbricht, in 2013. -

Naïve Or Desperate? Investors Continue to Be Swindled by Investment Schemes. Jonathan Hafen

Naïve or Desperate? Investors continue to be swindled by investment schemes. Jonathan Hafen Though the economy appears to be rebounding, many investors are still feeling the sting of having lost hefty percentages of their savings. Lower interest rates and returns on traditionally low risk investments put investors in a vulnerable position where they may feel the need to "catch up" to where they were a few years ago. Investors, particularly if they are elderly, trying to find better than prevailing returns may let their guard down to seemingly legitimate swindlers offering high return, "low-risk" investments. Fraudulent investment schemes come in all shapes and sizes, but generally have two common elements-they seem too good to be true and they are too good to be true. Eighty years ago, Charles Ponzi created his namesake scheme and investors are still falling for virtually identical scams today. Ponzi schemes promise either fixed rates of return above the prevailing market or exorbitant returns ranging from 45% to 100% and more. Early investors receive monthly, quarterly or annual interest from the cash generated from a widening pool of investors. Of course, they are receiving nothing more than a small portion of their own money back. The illusion of profit keeps the duped investors satisfied and delays the realization they have been tricked. Early investors usually play a part in keeping the scheme alive by telling friends or family of their good fortune. They essentially become references for new investors, which makes them unwitting accomplices. These scams always collapse under their own weight because new investments eventually slow and cannot sustain the rate of return promised as the number of investors grows. -

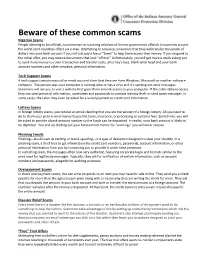

Beware of These Common Scams

Beware of these common scams Nigerian Scams People claiming to be officials, businessmen or surviving relatives of former government officials in countries around the world send countless offers via e-mail, attempting to convince consumers that they will transfer thousands of dollars into your bank account if you will just pay a fee or "taxes" to help them access their money. If you respond to the initial offer, you may receive documents that look "official." Unfortunately, you will get more e-mails asking you to send more money to cover transaction and transfer costs, attorney's fees, blank letterhead and your bank account numbers and other sensitive, personal information. Tech Support Scams A tech support person may call or email you and claim that they are from Windows, Microsoft or another software company. The person says your computer is running slow or has a virus and it’s sending out error messages. Scammers will ask you to visit a website that gives them remote access to your computer. If the caller obtains access they can steal personal information, usernames and passwords to commit identity theft or send spam messages. In some cases, the caller may even be asked for a wired payment or credit card information. Lottery Scams In foreign lottery scams, you receive an email claiming that you are the winner of a foreign lottery. All you need to do to claim your prize is send money to pay the taxes, insurance, or processing or customs fees. Sometimes, you will be asked to provide a bank account number so the funds can be deposited. -

Shadowcrew Organization Called 'One-Stop Online Marketplace for Identity Theft'

October 28, 2004 Department Of Justice CRM (202) 514-2007 TDD (202) 514-1888 WWW.USDOJ.GOV Nineteen Individuals Indicted in Internet 'Carding' Conspiracy Shadowcrew Organization Called 'One-Stop Online Marketplace for Identity Theft' WASHINGTON, D.C. - Attorney General John Ashcroft, Assistant Attorney General Christopher A. Wray of the Criminal Division, U.S. Attorney Christopher Christie of the District of New Jersey and United States Secret Service Director W. Ralph Basham today announced the indictment of 19 individuals who are alleged to have founded, moderated and operated "www.shadowcrew.com" -- one of the largest illegal online centers for trafficking in stolen identity information and documents, as well as stolen credit and debit card numbers. The 62-count indictment, returned by a federal grand jury in Newark, New Jersey today, alleges that the 19 individuals from across the United States and in several foreign countries conspired with others to operate "Shadowcrew," a website with approximately 4,000 members that was dedicated to facilitating malicious computer hacking and the dissemination of stolen credit card, debit card and bank account numbers and counterfeit identification documents, such as drivers' licenses, passports and Social Security cards. The indictment alleges a conspiracy to commit activity often referred to as "carding" -- the use of account numbers and counterfeit identity documents to complete identity theft and defraud banks and retailers. The indictment is a result of a year-long investigation undertaken by the United States Secret Service, working in cooperation with the U.S. Attorney's Office for the District of New Jersey, the Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section of the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice, and other U.S. -

Cadenza Document

Statewide Convictions by Offense (Summary) FORGERY/FRAUD 1/1/1999 to 12/31/2012 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 OFOF 1 1 FELC 5 7 3 11 16 10 8 18 12 15 9 8 21 27 FELD 846 926 1,229 1,279 1,155 1,104 1,184 1,171 1,008 762 716 537 646 799 AGMS 383 404 534 559 574 603 699 643 655 699 606 680 643 642 SRMS 16 15 7 15 16 12 4 20 9 20 21 16 40 58 SMMS 41 36 46 58 42 58 36 39 53 37 47 60 70 68 UNKN 87 46 27 19 12 2 Totals 1,379 1,434 1,846 1,941 1,815 1,788 1,931 1,891 1,737 1,533 1,401 1,301 1,420 1,594 FORGERY/FRAUD 1/1/1999 to 12/31/2012 1999 Convicting Chg Convicting Description Class Convictions 234.13(1)(C) FOOD STAMP FRAUD-FALSE STATEMENTS (AGMS) AGMS 1 234.13(1)(D) FOOD STAMP FRAUD-FALSE STATEMENTS (SRMS) SRMS 1 234.13(3)(E) FOOD STAMP FRAUD-UNLAWFUL COUPON USE (SMMS) SMMS 1 714.10 FRAUDULENT PRACTICE 2ND DEGREE - 1978 (FELD) FELD 82 714.11 DNU - FRAUDULENT PRACTICE IN THE THIRD DEGREE - AGMS 66 714.11(1) FRAUDULENT PRACTICE THIRD DEGREE--$500-UNDER $1000 (AGMS) AGMS 16 714.11(3) FRAUDULENT PRACTICE 3RD DEGREE-AMOUNT UNDETERMINABLE (AGMS) AGMS 6 714.12 FRAUDULENT PRACTICE 4TH DEGREE - 1978 (SRMS) SRMS 11 714.13 FRAUDULENT PRACTICE 5TH DEGREE - 1978 (SMMS) SMMS 28 714.1(3)-B DNU - THEFT BY DECEPTION (FELD) FELD 3 714.1(3)-C DNU - THEFT BY DECEPTION (AGMS) AGMS 2 714.1(3)-D DNU-THEFT BY DECEPTION (SMMS) SMMS 12 714.1(3)-E DNU-THEFT BY DECEPTION (SRMS) SRMS 3 714.9 FRAUDULENT PRACTICE 1ST DEGREE - 1978 (FELC) FELC 4 715.6 FALSE USE OF FIN.