Frames of Reference: "Table" and "Tableau" in Picasso's Collages and Constructions Author(S): Christine Poggi Source: Art Journal, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technology in the Fashion Industry: Designing with Digital Media

Lindenwood University Digital Commons@Lindenwood University Theses Theses & Dissertations Fall 8-2014 Technology in the Fashion Industry: Designing with Digital Media Adima Cope Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/theses Part of the Fashion Design Commons TECHNOLOGY IN THE FASHION INDUSTRY: DESIGNING WITH DIGITAL MEDIA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Art and Design Department in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts at Lindenwood University By Adima Cope Saint Charles, Missouri August 2014 Cope 2 Abstract Title of Thesis: Technology in the Fashion Industry: Designing with Digital Media Adima Cope, Master of Fine Art, 2014 Thesis Directed by: Chajuana V. Trawick, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Art and Design, Fashion Program Manager The fashion industry has advanced new technologies in the twenty-first century that has made producing apparel more cost effective with faster time-to-market capabilities and greatly reduced steps in the manufacturing process. The reasons for these improvements can be linked to new apparel computer-aided-design (CAD) technologies that have come about in the market as computers have advanced and grown in processing power and reduction in size since the 1980s. Computers are revolutionizing many industries and the way business is conducted in today’s modern workplace. The fashion industry has yet to convert all processes to digital means but advancements have been growing in popularity over the years and are certain to increase as the technologies available become better and more reliable. This raises the need for research to take place to survey the market and determine what types of software are available and the capabilities of the technologies. -

A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2014 The ubiC st's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Geoffrey David, "The ubC ist's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 584. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/584 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTRE: A STYISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912. by Geoffrey David Schwartz A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2014 ABSTRACT THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTE: A STYLISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912 by Geoffrey David Schwartz The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Kenneth Bendiner This thesis examines the stylistic and contextual significance of five Cubist cityscape pictures by Juan Gris from 1911 to 1912. These drawn and painted cityscapes depict specific views near Gris’ Bateau-Lavoir residence in Place Ravignan. Place Ravignan was a small square located off of rue Ravignan that became a central gathering space for local artists and laborers living in neighboring tenements. -

Montmartre the Tour: La Place Des Abbesses (The Abbesses Square), the Small Streets, La Place Du Tertre (The Tertre Square), Le Sacré-Coeur (The Sacred Heart)

MONTMARTRE THE TOUR: LA PLACE DES ABBESSES (THE ABBESSES SQUARE), THE SMALL STREETS, LA PLACE DU TERTRE (THE TERTRE SQUARE), LE SACRÉ-COEUR (THE SACRED HEART) LE SACRÉ-COEUR THE SMALL STREETS LA PLACE DU TERTRE LES ABBESSES Lenght: Means of locomotion: on foot - 3H00 walking, Access for persons with reduced - half a day: walking + visit of the mobility : no Sacré-Coeur, Total distance: 4km - the entire day: walking + visit of Starting point: Place des Abbesses the Sacré-Coeur, the Montmartre (metro line 12, Abbesses station, museum and the Dali area. or the Montmartrobus Abbesses station) Public: All restaurant, « Le Relais de la Butte » (The Mound Inn), once called « Chez Azon » (At Azon’s). At the beginning of the 20th century, Father Azon gladly welcomed and fed all the penniless artists from the bateau- lavoir who paid him with works of art... which did not prevent him from Take rue des Abbesses going bankrupt ! (Abbesses Street) on your right and keep going forward for about 50 Climb the steps of this Emile metres. Goudeau small square (ex Ravignan Square). It is the same quietness At the Abbesses passage entrance, impression that we found in the on your right, graffities, drawings, Place des Abbesses, with benches, stencils and other inlays are trees, the big Wallace fountain, and animating the walls. some funny graffities. Pay close attention, you will have the opportunity to see many others On your left, with your back turned throughout the walk. to the steps, stands a recently cleaned building with white blinds Carry on and take rue Ravignan and green doors is the famous (Ravignan Street) on your right. -

Pablo Picasso, Published by Christian Zervos, Which Places the Painter of the Demoiselles Davignon in the Context of His Own Work

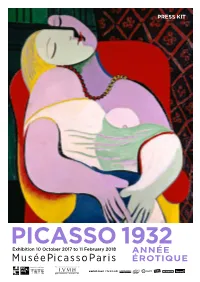

PRESS KIT PICASSO 1932 Exhibition 10 October 2017 to 11 February 2018 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE En partenariat avec Exposition réalisée grâce au soutien de 2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE From 10 October to the 11 February 2018 at Musée national Picasso-Paris The first exhibition dedicated to the work of an artist from January 1 to December 31, the exhibition Picasso 1932 will present essential masterpieces in Picassos career as Le Rêve (oil on canvas, private collection) and numerous archival documents that place the creations of this year in their context. This event, organized in partnership with the Tate Modern in London, invites the visitor to follow the production of a particularly rich year in a rigorously chronological journey. It will question the famous formula of the artist, according to which the work that is done is a way of keeping his journal? which implies the idea of a coincidence between life and creation. Among the milestones of this exceptional year are the series of bathers and the colorful portraits and compositions around the figure of Marie-Thérèse Walter, posing the question of his works relationship to surrealism. In parallel with these sensual and erotic works, the artist returns to the theme of the Crucifixion while Brassaï realizes in December a photographic reportage in his workshop of Boisgeloup. 1932 also saw the museification of Picassos work through the organization of retrospectives at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris and at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, which exhibited the Spanish painter to the public and critics for the first time since 1911. The year also marked the publication of the first volume of the Catalog raisonné of the work of Pablo Picasso, published by Christian Zervos, which places the painter of the Demoiselles dAvignon in the context of his own work. -

3"T *T CONVERSATIONS with the MASTER: PICASSO's DIALOGUES

3"t *t #8t CONVERSATIONS WITH THE MASTER: PICASSO'S DIALOGUES WITH VELAZQUEZ THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Joan C. McKinzey, B.F.A., M.F.A. Denton, Texas August 1997 N VM*B McKinzey, Joan C., Conversations with the master: Picasso's dialogues with Velazquez. Master of Arts (Art History), August 1997,177 pp., 112 illustrations, 63 titles. This thesis investigates the significance of Pablo Picasso's lifelong appropriation of formal elements from paintings by Diego Velazquez. Selected paintings and drawings by Picasso are examined and shown to refer to works by the seventeenth-century Spanish master. Throughout his career Picasso was influenced by Velazquez, as is demonstrated by analysis of works from the Blue and Rose periods, portraits of his children, wives and mistresses, and the musketeers of his last years. Picasso's masterwork of High Analytical Cubism, Man with a Pipe (Fort Worth, Texas, Kimbell Art Museum), is shown to contain references to Velazquez's masterpiece Las Meninas (Madrid, Prado). 3"t *t #8t CONVERSATIONS WITH THE MASTER: PICASSO'S DIALOGUES WITH VELAZQUEZ THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Joan C. McKinzey, B.F.A., M.F.A. Denton, Texas August 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to acknowledge Kurt Bakken for his artist's eye and for his kind permission to develop his original insight into a thesis. -

Artist Spotlight

ARTIST SPOTLIGHT Édouard Manet DAN SCOTT The Bridge BetweenÉdouard Realism Manet and Impressionism Édouard Manet (1832-1883) was a French painter who bridged the gap between Real- ism and Impressionism. In this ebook, I take a closer look at his life and art. Édouard Manet, Boating, 1874 2 Key Fact Here are some of the key facts and ideas about the life and art of Manet: • Unlike many of his contemporaries, he was fortunate enough to be born into a wealthy family in Paris on 23 January 1832. His father was a high-ranking judge and his mother had strong political connections, being the daughter of a diplomat and goddaughter of Charles Bernadotte, a Swedish crown prince. • His father expected him to follow in his footsteps down a career in law. However, with encouragement from his uncle, he was more interested in a career as a paint- er. His uncle would take him to the Louvre on numerous occasions to be inspired by the master paintings. • Before committing himself to the arts, he tried to join the Navy but failed his entry examination twice. Only then did his father give his reluctant acceptance for him to become an artist. • He trained under a skilled teacher and painter named Thomas Couture from 1850 to 1856. Below is one of Couture’s paintings, which is similar to the early work of Manet. I always find it interesting to see how much a teacher’s work can influence the work of their students. That is why you need to be selective with who you learn from. -

Shoeing the Roping Horse I

The Roping Horse ShoeingBy Michael Chance, CJF ?.*: &\ - Chronic shoe pulling is most often I&*: 7caused by bad management, such as - turning them out in hazardous envi- ronments, such as deep mud, fenc- ing on the ground and so on. This is not your fault, unless you don't point it out and show customers their roles and responsibilities. The management of the equine athlete is a team effort. Lameness is a common cause of gait and dub his hind foot if he were faults. Veterinarians play a key role weak in his stop. These are all and can make life less stressful, factors You must learn through provided you're fortunate enough to communication with riderltrainer have a good relationship with the and or using your observation skills. good doctors in your area. ~t~~amazing YOUshould have a good understanding how a chronic shoe puller is of the horse's job description. miraculously cured by a simple hock lubrication. Calf horses, like here are as many ways to shoe The average age the rope reiners are notoriously hard on their roping horses as there are You see at the top end of the game is hocks. It comes with the job, n horses. Each one is unique, 15-18years old. Many of these horses T reach the peak of their career with with its Own strengths and weak- existing maladies and management Over the years of practice and study, nesses. A sound horse with good soundness is the key factor of I've developed a picture in my mind conformation, in a desirable envi- these horses. -

O Ex, O -4-» 0)

o ex, o -4-» 0) CO H CO I—zI o p—I CO CO w P4 Terrace at Sainte-Adresse, by Claude Monet (1840-1926), Trench. About 1867. Oil on canvas, 38%, x S'Vs inches. Purchased with special contributions and purchase funds given or bequeathed by friends of the Museum, (>~.2ji Windows Open to Nature MARGARETTA M. SALINGER Associate Curator of European Paintings "Sainte-Adresse," wrote Monet in the early sixties, alluding to the physical aspect of the little seacoast town north of Le Havre and not to his frustrated life there among his exasperated relatives, "Sainte-Adresse - it's heavenly and every day I turn up things that are constantly more lovely. It's enough to drive one mad, I so much want to do it all!" This joyous appreciation, this impatient eagerness, from the most objective and consciously directed of the impressionist painters is echoed twenty-five years later in the bursting enthusiasm of one of Vincent van Gogh's letters written from Aries: "Nature here is so extraordinarily beautiful... I cannot paint it as lovely as it is." What other movement in the whole history of art is so marked by cheerfulness or reflects so much pure delight in life and nature as impressionism? The subject matter alone in dicates the happy things that attracted the young artists: pretty women, children, and pets; places of amusement - theaters, circuses, outdoor dance halls, regattas and sailing parties, restaurants and cafes; and most of all, nature herself, beaches and rivers, flowers and gardens. The question automatically arises why, confronted with so many agree able images, public and critics alike were outraged by what they saw, most of the latter nettled to the point of searing hostility. -

Pablo Picasso, One of the Most He Was Gradually Assimilated Into Their Dynamic and Influential Artists of Our Stimulating Intellectual Community

A Guide for Teachers National Gallery of Art,Washington PICASSO The Early Ye a r s 1892–1906 Teachers’ Guide This teachers’ guide investigates three National G a l l e ry of A rt paintings included in the exhibition P i c a s s o :The Early Ye a rs, 1 8 9 2 – 1 9 0 6.This guide is written for teachers of middle and high school stu- d e n t s . It includes background info r m a t i o n , d i s c u s s i o n questions and suggested activities.A dditional info r m a- tion is available on the National Gallery ’s web site at h t t p : / / w w w. n g a . gov. Prepared by the Department of Teacher & School Programs and produced by the D e p a rtment of Education Publ i c a t i o n s , Education Division, National Gallery of A rt . ©1997 Board of Tru s t e e s , National Gallery of A rt ,Wa s h i n g t o n . Images in this guide are ©1997 Estate of Pa blo Picasso / A rtists Rights Society (ARS), New Yo rk PICASSO:The EarlyYears, 1892–1906 Pablo Picasso, one of the most he was gradually assimilated into their dynamic and influential artists of our stimulating intellectual community. century, achieved success in drawing, Although Picasso benefited greatly printmaking, sculpture, and ceramics from the artistic atmosphere in Paris as well as in painting. He experiment- and his circle of friends, he was often ed with a number of different artistic lonely, unhappy, and terribly poor. -

The Artists of Les Xx: Seeking and Responding to the Lure of Spain

THE ARTISTS OF LES XX: SEEKING AND RESPONDING TO THE LURE OF SPAIN by CAROLINE CONZATTI (Under the Direction of Alisa Luxenberg) ABSTRACT The artists’ group Les XX existed in Brussels from 1883-1893. An interest in Spain pervaded their member artists, other artists invited to the their salons, and the authors associated with the group. This interest manifested itself in a variety of ways, including references to Spanish art and culture in artists’ personal letters or writings, in written works such as books on Spanish art or travel and journal articles, and lastly in visual works with overtly Spanish subjects or subjects that exhibited the influence of Spanish art. Many of these examples incorporate stereotypes of Spaniards that had existed for hundreds of years. The work of Goya was particularly interesting to some members of Les XX, as he was a printmaker and an artist who created work containing social commentary. INDEX WORDS: Les XX, Dario de Regoyos, Henry de Groux, James Ensor, Black Legend, Francisco Lucientes y Goya THE ARTISTS OF LES XX: SEEKING AND RESPONDING TO THE LURE OF SPAIN by CAROLINE CONZATTI Bachelor of Arts, Manhattanville College, 1999 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2005 © 2005 CAROLINE CONZATTI All Rights Reserved THE ARTISTS OF LES XX: SEEKING AND RESONDING TO THE LURE OF SPAIN by CAROLINE CONZATTI Major Professor: Alisa Luxenberg Committee: Evan Firestone Janice Simon Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2005 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thanks the entire art history department at the University of Georgia for their help and support while I was pursuing my master’s degree, specifically my advisor, Dr. -

Rope Circles and Giant Trees: Making History Come Alive Robert Millward

Social Studies and the Young Learner 19 (3), pp. 15–19 ©2007 National Council for the Social Studies Rope Circles and Giant Trees: Making History Come Alive Robert Millward Every year, I dine in an imaginary hollow cottonwood tree with primary lead plates at various locations on the and intermediate students. This is how I begin a series of lessons on the French and Allegheny and Ohio River thus claim- Indian War era. Students in fourth grade through middle school can get a real feel ing the territory for France. Griffing’s for what the colonial frontier was like when I incorporate physical activity, paintings, painting helps to make the expedition artifacts, diaries and discussions into the lessons. come alive. It was this expedition that provoked great concerns among the Big Trees and 15 feet in circumference and white colonists of Virginia and Pennsylvania, I begin the first lesson by dividing the pines were often 10 feet in circumfer- since they too claimed ownership of class into four small groups. One group ence. the Ohio Valley. It was these compet- is given a 45-foot length rope and told At this point I show the students ing claims that led to The French and to make a rope circle on the floor and “We Dined in a Hollow Cottonwood Indian War. then to sit inside the circle. A second Tree,” a painting by Robert Griffing, group constructs a circle with an 18-foot which depicts people meeting inside the Items of Trade length of rope. The third group forms a hollow trunk of a giant cottonwood!1 I then introduce the students to the lives circle with a 15-foot section of rope. -

Rustic Rope © Melissa Grakowsky Shippee

Difficulty: ««¶¶¶ Advanced Beginner www.mgsdesigns.net Rustic Rope © Melissa Grakowsky Shippee This necklace features 13mm antique cut beads (also called English cuts) from Perry Bookstein plus unusual Japanese 8/0 cut beads and 11/0 seed beads. If you can’t find these unusual materials, you can substitute the more common 10mm antique cut beads, 11/0 seed beads, and 15/0 seed beads. Page 2 What You’ll Need... Symbol/Supply Name # Weight Toho 8/0 cut beads, matte bronze 8/0 1269 32g Toho 11/0 seed bead, bronze 11/0 288 2g Czech antique cuts, (aka English antique cut 10 cuts), aqua gold luster Notions Size 12 to 13 beading needles, beading thread (8lb Fireline recommended) Tools Scissors, beading mat. Techniques Tubular herringbone stitch, peyote stitch. About the diagrams... Beads already added when you start a step are shown new in the diagram in color with a normal outline. Beads you need to add in the current step are shown with a red outline. Thread paths going through beads are dashed, and thread coming out of beads is solid. Old thread paths old are not shown. The arrow represents the needle. The dot indicates the start of the thread path. Page 3 Glossary stitch through - v. To go through; put the needle through; needle through. stitch - n. A bead or set of beads picked up and added to beadwork and the beads stitched through; one set of a repeat. pick up - v. To put on your needle, ie. “pick up three 11As”. step up - v. To go through without adding beads, usually referring to the first bead(s) in the row being completed, in order to get the thread in place to start the next row.