Getting to Know Rodgers and Hammerstein: Education And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0

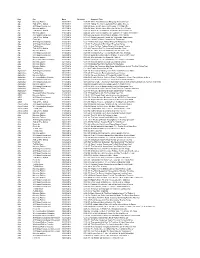

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0:04:09 When Should Seniors Hang Up The Car Keys? Age Talk Of The Nation 10/15/2012 0:30:20 Taking The Car Keys Away From Older Drivers Age All Things Considered 10/16/2012 0:05:29 Home Health Aides: In Demand, Yet Paid Little Age Morning Edition 10/17/2012 0:04:04 Home Health Aides Often As Old As Their Clients Age Talk Of The Nation 10/25/2012 0:30:21 'Elders' Seek Solutions To World's Worst Problems Age Morning Edition 11/01/2012 0:04:44 Older Voters Could Decide Outcome In Volatile Wisconsin Age All Things Considered 11/01/2012 0:03:24 Low-Income New Yorkers Struggle After Sandy Age Talk Of The Nation 11/01/2012 0:16:43 Sandy Especially Tough On Vulnerable Populations Age Fresh Air 11/05/2012 0:06:34 Caring For Mom, Dreaming Of 'Elsewhere' Age All Things Considered 11/06/2012 0:02:48 New York City's Elderly Worry As Temperatures Dip Age All Things Considered 11/09/2012 0:03:00 The Benefit Of Birthdays? Freebies Galore Age Tell Me More 11/12/2012 0:14:28 How To Start Talking Details With Aging Parents Age Talk Of The Nation 11/28/2012 0:30:18 Preparing For The Looming Dementia Crisis Age Morning Edition 11/29/2012 0:04:15 The Hidden Costs Of Raising The Medicare Age Age All Things Considered 11/30/2012 0:03:59 Immigrants Key To Looming Health Aide Shortage Age All Things Considered 12/04/2012 0:03:52 Social Security's COLA: At Stake In 'Fiscal Cliff' Talks? Age Morning Edition 12/06/2012 0:03:49 Why It's Easier To Scam The Elderly Age Weekend Edition Saturday 12/08/2012 -

Clark Spring Semester 2020 Homeschoole MT

Clark Spring Semester 2020 Homeschoole MT JENNA: In the early 1940s, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein III’s ‘Oklahoma!,’ adapted from a play written by Claremore playwright Lynn Riggs, opened on Broadway. It was the first musical they wrote together.. KYLE: Each had already found success on Broadway: Rodgers, having written a series of popular musicals with lyricist Lorenz Hart, and Hammerstein, having written the monumental classic, ‘Show Boat.’ But together with ‘Oklahoma!', they would change musical theatre forever. “Oh! What a Beautiful Mornin’” There's a bright golden haze on the meadow There's a bright golden haze on the meadow The corn is as high as an elephant's eye And it looks like it's climbing clear up to the sky Oh, what a beautiful mornin' Oh, what a beautiful day I've got a beautiful feeling Everything's going my way All the cattle are standing like statues All the cattle are standing like statues They don't turn their heads as they see me ride by But a little brown maverick is winking her eye Oh, what a beautiful mornin' I've got a beautiful feeling Everything's going my way All the sounds of the earth are like music All the sounds of the earth are like music The breeze is so busy, it don't miss a tree And an old weeping willow is laughing at me Oh, what a beautiful mornin' Oh, what a beautiful day I've got a beautiful feeling Everything's going my way Oh, what a beautiful day ALEXA I: With its character-driven songs and innovative use of dance, ‘Oklahoma’ elevated how musicals were written. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Classical Voice Grade 3

Classical Voice Grade 3 Length of examination: 20 minutes Examination Fee: Please consult our website for the schedule of fees: www.conservatorycanada.ca Corequisite: There is no written examination corequisite for the completion of Grade 3. Note: The Grade 3 examination is designed for younger singers. It is recommended that mature beginners enter the examination program at the Grade 4 level. REQUIREMENTS & MARKING Requirements Total Marks List A 15 Repertoire List B 15 4 pieces of contrasting styles List B or C 15 Own Choice Piece 12 Technique Listed exercises 15 Sight Reading Rhythm (3) Singing (7) 10 Aural Tests Clap Back (3) Triads (2) Scales (2) Chord Tones (3) 10 Background Information 8 Total Possible Marks 100 *One bonus mark will be awarded for including a repertoire piece by a Canadian composer CONSERVATORY CANADA ™ GRADE 3 AUGUST 2018 1 REPERTOIRE ● Candidates must be prepared to sing four pieces varying in key, tempo, mood, and subject, with at least three different composers being represented to receive full marks: ● One List A piece ● One List B piece ● One List B o r List C piece ● One Own Choice piece: ● This piece may be chosen from the repertoire list (Classical or Contemporary Idioms) or may be a free choice (not chosen from the repertoire list). ● Free choice pieces do not require approval. ● Must be at or above the Grade 3 level (can be more than one level above). ● This piece must be suitable for the candidate’s voice and age. ● Vocal duets are acceptable, provided the candidate’s part is equivalent in difficulty to Grade 3, and a second vocalist covers the second part. -

Ferenc Molnar

L I L I O M A LEGEND IN SEVEN SCENES BY FERENC MOLNAR EDITED AND ADAPTED BY MARK JACKSON FROM AN ENGLISH TEXT BY BENJAMIN F. GLAZER v2.5 This adaptation of Liliom Copyright © 2014 Mark Jackson All rights strictly reserved. For all inquiries regarding production, publication, or any other public or private use of this play in part or in whole, please contact: Mark Jackson email: [email protected] www.markjackson-theatermaker.com CAST OF CHARACTERS (4w;4m) Marie / Stenographer Julie / Louise Mrs Muskat Liliom Policeman / The Guard Mrs Hollunder / The Magistrate Ficsur / A Poorly Dressed Man Wolf Beifeld / Linzman / Carpenter / A Richly Dressed Man SCENES (done minimally and expressively) FIRST SCENE — A lonely place in the park. SECOND SCENE — Mrs. Hollunder’s photographic studio. THIRD SCENE — Same as scene two. FOURTH SCENE — A railroad embankment outside the city. FIFTH SCENE — Same as scene two SIXTH SCENE — A courtroom in the beyond. SEVENTH SCENE — Julie’s garden, sixteen years later. A NOTE (on time & place) The current draft retains Molnar’s original 1909 Budapest setting. With minimal adjustments the play could easily be reset in early twentieth century America. Though I wonder whether certain of the social attitudes—toward soldiers, for example— would transfer neatly, certainly an American setting could embody Molnar’s complex critique of gender, class, and racial tensions. That said, retaining Molnar’s original setting perhaps now adds to his intention to fashion an expressionist theatrical legend, while still allowing for the strikingly contemporary themes that prompted me to write this adaptation—among them how Liliom struggles and fails to change in the face of economic and social flux; that women run the businesses, Heaven included; and Julie’s independent, confidently anti-conventional point of view. -

The Sleeping Beauty Untouchable Swan Lake In

THE ROYAL BALLET Director KEVIN O’HARE CBE Founder DAME NINETTE DE VALOIS OM CH DBE Founder Choreographer SIR FREDERICK ASHTON OM CH CBE Founder Music Director CONSTANT LAMBERT Prima Ballerina Assoluta DAME MARGOT FONTEYN DBE THE ROYAL BALLET: BACK ON STAGE Conductor JONATHAN LO ELITE SYNCOPATIONS Piano Conductor ROBERT CLARK ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE Concert Master VASKO VASSILEV Introduced by ANITA RANI FRIDAY 9 OCTOBER 2020 This performance is dedicated to the late Ian Taylor, former Chair of the Board of Trustees, in grateful recognition of his exceptional service and philanthropy. Generous philanthropic support from AUD JEBSEN THE SLEEPING BEAUTY OVERTURE Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE UNTOUCHABLE EXCERPT Choreography HOFESH SHECHTER Music HOFESH SHECHTER and NELL CATCHPOLE Dancers LUCA ACRI, MICA BRADBURY, ANNETTE BUVOLI, HARRY CHURCHES, ASHLEY DEAN, LEO DIXON, TÉO DUBREUIL, BENJAMIN ELLA, ISABELLA GASPARINI, HANNAH GRENNELL, JAMES HAY, JOSHUA JUNKER, PAUL KAY, ISABEL LUBACH, KRISTEN MCNALLY, AIDEN O’BRIEN, ROMANY PAJDAK, CALVIN RICHARDSON, FRANCISCO SERRANO and DAVID YUDES SWAN LAKE ACT II PAS DE DEUX Choreography LEV IVANOV Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY Costume designer JOHN MACFARLANE ODETTE AKANE TAKADA PRINCE SIEGFRIED FEDERICO BONELLI IN OUR WISHES Choreography CATHY MARSTON Music SERGEY RACHMANINOFF Costume designer ROKSANDA Dancers FUMI KANEKO and REECE CLARKE Solo piano KATE SHIPWAY JEWELS ‘DIAMONDS’ PAS DE DEUX Choreography GEORGE BALANCHINE Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY -

What's the Use of Wondering If He's Good Or Bad?: Carousel and The

What’s the Use of Wondering if He’s Good or Bad?: Carousel and the Presentation of Domestic Violence in Musicals. Patricia ÁLVAREZ CALDAS Universidad de Santiago de Compostela [email protected] Recibido: 15.09.2012 Aceptado: 30.09.2012 ABSTRACT The analysis of the 1956 film Carousel (Dir. Henry King), which was based on the 1945 play by Rodgers and Hammerstein, provides a suitable example of a musical with explicit allusions to male physical aggression over two women: the wife and the daughter. The issue of domestic violence appears, thus, in a film genre in which serious topics such as these are rarely present. The film provide an opportunity to study how the expectations and the conventions brought up by this genre are capable of shaping and transforming the presentation of Domestic Violence. Because the audience had to sympathise with the protagonists, the plot was arranged to fulfil the conventional pattern of a romantic story inducing audiences forget about the dark themes that are being portrayed on screen. Key words: Domestic violence, film, musical, cultural studies. ¿De qué sirve preocuparse por si es bueno o malo?: Carrusel y la presentación de la violencia doméstica en los musicales. RESUMEN La película Carrusel (dirigida por Henry King en 1956 y basada en la obra de Rodgers y Hammerstein de 1945), nos ofrece un gran ejemplo de un musical que realiza alusiones explícitas a las agresiones que ejerce el protagonista masculino sobre su esposa y su hija. El tema de la violencia doméstica aparece así en un género fílmico en el que este tipo de tratamientos rara vez están presentes. -

Finding, Reclaiming, and Reinventing Identity Through DNA: the DNA Trail

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 23 (2012) Finding, Reclaiming, and Reinventing Identity through DNA: The DNA Trail Yuko KURAHASHI* The DNA Trail: A Genealogy of Short Plays about Ancestry, Identity, and Utter Confusion (2011) is a collection of seven fifteen-to-twenty minute plays by veteran Asian American playwrights whose plays have been staged nationally and internationally since the 1980s. The plays include Philip Kan Gotanda’s “Child Is Father to Man,” Velina Hasu Houston’s “Mother Road,” David Henry Hwang’s “A Very DNA Reunion,” Elizabeth Wong’s “Finding Your Inner Zulu,” Shishir Kurup’s “Bolt from the Blue,” Lina Patel’s “That Could Be You,” and Jamil Khoury’s “WASP: White Arab Slovak Pole.” Conceived by Jamil Khoury and commissioned and developed by Silk Road Theatre Project in Chicago in association with the Goodman Theatre, a full production of the seven plays was mounted at Silk Road Theatre Project in March and April 2010.1 On January 22, 2011, Visions and Voices: The USC Arts and Humanities Initiative presented a staged reading at the Uni- versity of Southern California, Los Angeles, using revised scripts. The staged reading was directed by Goodman Theatre associate producer Steve Scott, who had also directed the original production.2 San Francisco–based playwright Gotanda has written plays that reflect his yearning to learn the stories of his Japanese American parents, and their friends and relatives. His plays include A Song for a Nisei Fisherman (1980), The Wash (1985), Ballad of Yachiyo (1996), and Sisters *Associate Professor, Kent State University 285 286 YUKO KURAHASHI Matsumoto (1997). -

2013 Winners — Broadway.Com Audience Choice Awards

HOME / 2013 WINNERS / ABOUT / BUZZ / VIDEO / PAST WINNERS And the Winners Are... Winners are marked below in bold. FAVORITE NEW MUSICAL A Christmas Story: The Musical (Book by Joseph Robinette; Music and Lyrics by Benj Pasek and Justin Paul) Bring It On: The Musical (Book by Jeff Whitty; Music by Tom Kitt and Lin-Manuel Miranda; Lyrics by Amanda Green and Lin-Manuel Miranda) Kinky Boots (Book by Harvey Fierstein; Music and Lyrics by Cyndi Lauper) Matilda (Book by Dennis Kelly; Music and Lyrics by Tim Minchin) Motown: The Musical (Book by Berry Gordy Jr.) FAVORITE NEW PLAY *Breakfast at Tiffany’s byby RichardRichard GreenbergGreenberg Lucky Guy by Nora Ephron The Nance by Douglas Carter Beane The Performers by David West Read Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike by Christopher Durang FAVORITE MUSICAL REVIVAL *Annie Jekyll & Hyde The Mystery of Edwin Drood Pippin Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Cinderella FAVORITE PLAY REVIVAL Cat on a Hot Tin Roof Harvey The Heiress *Macbeth Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? FAVORITE LONG-RUNNING SHOW The Book of Mormon The Lion King Newsies The Phantom of the Opera *Wicked FAVORITE TOUR Anything Goes The Book of Mormon Les Miserables The Lion King *Wicked FAVORITE ACTOR IN A MUSICAL Bertie Carvel, Matilda Will Chase, The Mystery of Edwin Drood Santino Fontana, Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Cinderella *Billy Porter,, Kinky Boots Anthony Warlow, Annie FAVORITE ACTRESS IN A MUSICAL Annaleigh Ashford, Kinky Boots Stephanie J. Block, The Mystery of Edwin Drood Victoria Clark, Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Cinderella Patina Miller, Pippin *Laura Osnes,, Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Cinderella FAVORITE ACTOR IN A PLAY Norbert Leo Butz, Dead Accounts *Alan Cumming, Macbeth Tom Hanks, Lucky Guy Nathan Lane, The Nance Jim Parsons, Harvey FAVORITE ACTRESS IN A PLAY Jessica Chastain, The Heiress Scarlett Johansson, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof Patti LuPone, The Anarchist *Bette Midler, I’llI’ll EatEat YouYou Last:Last: AA ChatChat withwith SueSue MengersMengers Sigourney Weaver, Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike FAVORITE DIVA PERFORMANCE *Stephanie J. -

Mactheatre Theatre Departme

Think You Need A BFA? ................................................................................................................... 3 Is a BFA Degree Part of the Recipe for Musical Theater Success? ................................................. 7 A Little Quiz ................................................................................................................................... 12 Broadway's Big 10: Top Colleges Currently Represented on Currently Running Shows .............. 14 Monthly College Planning Guide For Visual & Performing Arts Students. ................................... 18 Theatre and Musical Theatre College Audition Timeline in a Nutshell ........................................ 48 Gain An Edge Over The Summer ................................................................................................... 50 6 Keys To Choosing The Perfect College For The Arts. ................................................................. 53 The National Association for College Admission Counseling Performing and Visual Arts Fairs in Houston & Dallas. ......................................................................................................................... 55 Unifieds ......................................................................................................................................... 58 TX Thespian Festival College Auditions......................................................................................... 68 Theatre College-Bound Resource Index. ..................................................................................... -

View Was Provided by the National Endowment for the Arts

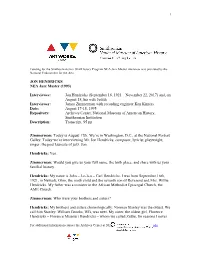

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. JON HENDRICKS NEA Jazz Master (1993) Interviewee: Jon Hendricks (September 16, 1921 – November 22, 2017) and, on August 18, his wife Judith Interviewer: James Zimmerman with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: August 17-18, 1995 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 95 pp. Zimmerman: Today is August 17th. We’re in Washington, D.C., at the National Portrait Galley. Today we’re interviewing Mr. Jon Hendricks, composer, lyricist, playwright, singer: the poet laureate of jazz. Jon. Hendricks: Yes. Zimmerman: Would you give us your full name, the birth place, and share with us your familial history. Hendricks: My name is John – J-o-h-n – Carl Hendricks. I was born September 16th, 1921, in Newark, Ohio, the ninth child and the seventh son of Reverend and Mrs. Willie Hendricks. My father was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the AME Church. Zimmerman: Who were your brothers and sisters? Hendricks: My brothers and sisters chronologically: Norman Stanley was the oldest. We call him Stanley. William Brooks, WB, was next. My sister, the oldest girl, Florence Hendricks – Florence Missouri Hendricks – whom we called Zuttie, for reasons I never For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 really found out – was next. Then Charles Lancel Hendricks, who is surviving, came next. Stuart Devon Hendricks was next. Then my second sister, Vivian Christina Hendricks, was next. -

The Sam Eskin Collection, 1939-1969, AFC 1999/004

The Sam Eskin Collection, 1939 – 1969 AFC 1999/004 Prepared by Sondra Smolek, Patricia K. Baughman, T. Chris Aplin, Judy Ng, and Mari Isaacs August 2004 Library of Congress American Folklife Center Washington, D. C. Table of Contents Collection Summary Collection Concordance by Format Administrative Information Provenance Processing History Location of Materials Access Restrictions Related Collections Preferred Citation The Collector Key Subjects Subjects Corporate Subjects Music Genres Media Formats Recording Locations Field Recording Performers Correspondents Collectors Scope and Content Note Collection Inventory and Description SERIES I: MANUSCRIPT MATERIAL SERIES II: SOUND RECORDINGS SERIES III: GRAPHIC IMAGES SERIES IV: ELECTRONIC MEDIA Appendices Appendix A: Complete listing of recording locations Appendix B: Complete listing of performers Appendix C: Concordance listing original field recordings, corresponding AFS reference copies, and identification numbers Appendix D: Complete listing of commercial recordings transferred to the Motion Picture, Broadcast, and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress 1 Collection Summary Call Number: AFC 1999/004 Creator: Eskin, Sam, 1898-1974 Title: The Sam Eskin Collection, 1938-1969 Contents: 469 containers; 56.5 linear feet; 16,568 items (15,795 manuscripts, 715 sound recordings, and 57 graphic materials) Repository: Archive of Folk Culture, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: This collection consists of materials gathered and arranged by Sam Eskin, an ethnomusicologist who recorded and transcribed folk music he encountered on his travels across the United States and abroad. From 1938 to 1952, the majority of Eskin’s manuscripts and field recordings document his growing interest in the American folk music revival. From 1953 to 1969, the scope of his audio collection expands to include musical and cultural traditions from Latin America, the British Isles, the Middle East, the Caribbean, and East Asia.