Open PDF 367KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP Chancellor of the Exchequer HM Treasury 1 Horse Guards Road London SW1A 2HQ

Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP Chancellor of the Exchequer HM Treasury 1 Horse Guards Road London SW1A 2HQ Dear Chancellor, Budget Measures to Support Hospitality and Tourism We are writing today as members and supporters of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Hospitality and Tourism ahead of the Budget on 3rd March. As you will of course be aware, hospitality and tourism are vital to the UK’s economy along with the livelihoods and wellbeing of millions of people across the UK. The pandemic has amplified this, with its impacts illustrating the pan-UK nature of these sectors, the economic benefits they generate, and the wider social and wellbeing benefits that they provide. The role that these sectors play in terms of boosting local, civic pride in all our constituencies, and the strong sense of community that they foster, should not be underestimated. It is well-established that people relate to their local town centres, high streets and community hubs, of which the hospitality and tourism sectors are an essential part. The latest figures from 2020 highlight the significant impact that the virus has had on these industries. In 2020, the hospitality sector has seen a sales drop of 53.8%, equating to a loss in revenue of £72 billion. This decline has impacted the UK’s national economy by taking off around 2 percentage points from total GDP. For hospitality, this downturn is already estimated to be over 10 times worse than the impact of the financial crisis. It is estimated that employment in the sector has dropped by over 1 million jobs. -

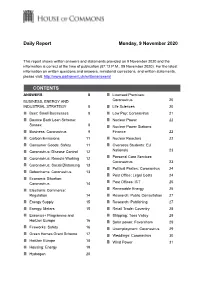

Daily Report Monday, 9 November 2020 CONTENTS

Daily Report Monday, 9 November 2020 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 9 November 2020 and the information is correct at the time of publication (07:12 P.M., 09 November 2020). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 8 Licensed Premises: BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Coronavirus 20 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 8 Life Sciences 20 Beer: Small Businesses 8 Low Pay: Coronavirus 21 Bounce Back Loan Scheme: Nuclear Power 22 Sussex 8 Nuclear Power Stations: Business: Coronavirus 9 Finance 22 Carbon Emissions 11 Nuclear Reactors 22 Consumer Goods: Safety 11 Overseas Students: EU Coronavirus: Disease Control 12 Nationals 23 Coronavirus: Remote Working 12 Personal Care Services: Coronavirus 23 Coronavirus: Social Distancing 13 Political Parties: Coronavirus 24 Debenhams: Coronavirus 13 Post Office: Legal Costs 24 Economic Situation: Coronavirus 14 Post Offices: ICT 25 Electronic Commerce: Renewable Energy 25 Regulation 14 Research: Public Consultation 27 Energy Supply 15 Research: Publishing 27 Energy: Meters 15 Retail Trade: Coventry 28 Erasmus+ Programme and Shipping: Tees Valley 28 Horizon Europe 16 Solar power: Faversham 29 Fireworks: Safety 16 Unemployment: Coronavirus 29 Green Homes Grant Scheme 17 Weddings: Coronavirus 30 Horizon Europe 18 Wind Power 31 Housing: Energy 19 Hydrogen 20 CABINET OFFICE 31 Musicians: Coronavirus 44 Ballot Papers: Visual Skateboarding: Coronavirus 44 Impairment 31 -

Daily Report Thursday, 29 April 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 29 April 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 29 April 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (04:42 P.M., 29 April 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 11 Energy Intensive Industries: ATTORNEY GENERAL 11 Biofuels 18 Crown Prosecution Service: Environment Protection: Job Training 11 Creation 19 Sentencing: Appeals 11 EU Grants and Loans: Iron and Steel 19 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 12 Facebook: Advertising 20 Aviation and Shipping: Carbon Foreign Investment in UK: Budgets 12 National Security 20 Bereavement Leave 12 Help to Grow Scheme 20 Business Premises: Horizon Europe: Quantum Coronavirus 12 Technology and Space 21 Carbon Emissions 13 Horticulture: Job Creation 21 Clean Technology Fund 13 Housing: Natural Gas 21 Companies: West Midlands 13 Local Government Finance: Job Creation 22 Coronavirus: Vaccination 13 Members: Correspondence 22 Deep Sea Mining: Reviews 14 Modern Working Practices Economic Situation: Holiday Review 22 Leave 14 Overseas Aid: China 23 Electric Vehicles: Batteries 15 Park Homes: Energy Supply 23 Electricity: Billing 15 Ports: Scotland 24 Employment Agencies 16 Post Offices: ICT 24 Employment Agencies: Pay 16 Remote Working: Coronavirus 24 Employment Agency Standards Inspectorate and Renewable Energy: Finance 24 National Minimum Wage Research: Africa 25 Enforcement Unit 17 Summertime -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

Community Sponsorship Explained

Community Sponsorship Explained: Community Sponsorship (CS) was introduced in 2016 by the then Prime Minister David Cameron and is a Home Office-backed scheme which allows friends and neighbours to resettle refugees in their community. CS is part of the VPRS programme – also known as the Syrian scheme – which was launched in 2015 where the Conservative Government committed to welcome 20,000 refugees by 2020. When resettlement flights were halted, 19,768 refugees had been resettled across the UK by Local Authorities and Community Sponsorship Groups. When flights resume, and 232 refugees have arrived, we will see the launch of a new resettlement programme – UKRS, where local authorities will resettle 5,000 refugees in one year and every refugee resettled through CS will be in addition to, not part of government pledges. UKRS HAS GOVERNMENT SUPPORT UP TO MARCH 2021, THE SCHEME HAS NOT BEEN GIVEN APPROVAL BEYOND THIS DATE SO FAR. Numbers: To date, 449 refugees have been welcomed by 91 Community Sponsorship Groups across the UK. 20% of these refugees have arrived in the South West of England. Currently, 150 Groups are working through applications to be ready to welcome refugees when resettlement flights begin again. WE NEED FLIGHTS TO RESUME URGENTLY TO BE ABLE TO OFFER A SAFE AND LEGAL PATHWAY FOR THE RESETTLEMENT OF REFUGEES. At the time of writing, the South West has the second most number of Community Sponsorship Groups in the whole of the UK. https://resetuk.org/blogs/community-sponsorship-uk-august-2020 Community Impact: Community Sponsorship isn’t about one person or one organisation, it’s about individuals and communities coming together to use their skills and experience to welcome people just like them. -

House of Commons Official Report

Wednesday Volume 691 17 March 2021 No. 192 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 17 March 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 303 17 MARCH 2021 304 Simon Hart: The best way of avoiding that outcome House of Commons is for the Welsh Government to get behind the scheme and support a project that is endorsed by local authorities and port authorities in Wales, and to encourage jobs Wednesday 17 March 2021 and livelihoods in that way. Every single day that they leave it—on the basis of the “not invented here” The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock syndrome—will cost jobs and livelihoods. My message to the hon. Gentleman is get hold of the Welsh Government and encourage them to come to the party. PRAYERS The Union [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Virtual participation in proceedings commenced (Orders, Anne McLaughlin (Glasgow North East) (SNP): What 4 June and 30 December 2020). recent assessment his Department has made of the [NB: [V] denotes a Member participating virtually.] strength of the Union between Wales and the rest of the UK. [913410] Oral Answers to Questions Andrew Bowie (West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine) (Con): What steps his Department is taking to strengthen the Union. [913417] WALES The Secretary of State for Wales (Simon Hart): As the vaccine roll-out has shown, our four nations are The Secretary of State was asked— safer, stronger and more prosperous together, and I Liverpool City Region Freeport look forward to the people of Wales giving a resounding endorsement of the Union at the Senedd elections in Mr David Jones (Clwyd West) (Con): What discussions May. -

Mps Back News Media During Coronavirus Outbreak

MPs Back News Media During Coronavirus Outbreak The Maidenhead Advertiser is a highly respected It is really important that people are able to access local newspaper and so it is right that the local news to gain an understanding of what is going Government has offered support through a number on in their area. The country’s news media - broadcast, print and of schemes which have been welcomed by Baylis online - are fulfilling a vital role ensuring people Media Ltd. receive accurate and timely health advice from Newspapers are absolutely vital when it comes to reporting on some of the key messages that we all the NHS and Public Health England during the However, an extension of the business rates holiday need to take on board so we can tackle this virus. pandemic, so everyone understands how to local publishers would help to ease the I hope some clarity and guidance can be issued to important it is to follow the advice to stay at considerable pressure they are currently facing and make sure it is understood that newspaper deliveries home in order to protect the NHS and save lives. enable local newspapers to continue to produce can – and should – still take place. trusted news and information at this time. … Home deliveries are an important part of this battle to As a vital part of the local community, we must make keep people self-isolating. sure The Maidenhead Advertiser can remain open for business. Rt Hon Oliver Dowden CBE MP – Rt Hon Gavin Williamson CBE Rt Hon Theresa May MP – Hertsmere and Secretary of State for MP – South Staffordshire and Maidenhead, Conservative Party Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, Secretary of State for Education, Conservative Party Conservative Party MPs Back News Media During Coronavirus Outbreak We need to do everything we can do in order to make sure we have a viable local newspaper when we come through the other side of this crisis. -

London Manchester Number of Employees by Parliamentary

Constituency MP Employees Constituency MP Employees Aberavon Stephen Kinnock 8 Jacobs UK Ltd 1 TWI Ltd 8 KAEFER Limited 18 Aberconwy Robin Millar 4 KDC Contractors Ltd 7 Dounreay Matom Limited 4 Kier Infrastructure and Overseas Ltd Thurso, Caithness 50 Aberdeen North Kirsty Blackman 6 Matom Limited gov.uk/government/organisations/dounreay 9 Bury North Salford SNC-Lavalin/Atkins 1 Mott MacDonald Ltd 2 SLC: Dounreay Site Restoration Ltd Manchester & Eccles Thornton Tomasetti 5 URENCO 485 PBO: Cavendish Dounreay Partnership Ltd Worsley & Aberdeen South Stephen Flynn 2 URENCO Nuclear Stewardship 84 (Cavendish Nuclear, Jacobs, Amentum) Eccles South AECOM 2 Coatbridge, Chryston & Bellshill Steven Bonnar 71 Lifetime: 1955–1994 Airdrie & Shotts Neil Gray 70 Jacobs UK Ltd 43 Operation: Development of prototype fast Balfour Beatty Kilpatrick 22 Scottish Enterprise 1 breeder reactors Bolton West BRC Reinforcement Ltd 41 SNC-Lavalin/Atkins 27 People: More than 600 ENGIE UK 3 Copeland Trudy Harrison 13,314 Caithness, Sutherland & Easter Ross Wigan Morgan Sindall Infrastructure 4 AECOM 11 Aldershot Leo Docherty 62 ARUP 46 Fluor Corporation 12 Assystem UK Ltd 27 Mirion Technologies (IST) Limited 49 Balfour Beatty Kilpatrick 151 NuScale Power 1 Bechtel 2 Manchester Aldridge-Brownhills Wendy Norton 19 Bureau Veritas UK Ltd 71 The UK Civil Nuclear Industry Central Stainless Metalcraft (Chatteris) Ltd 19 Capita Group 382 Altrincham & Sale West Sir Graham Brady 92 Capula Ltd 10 Mott MacDonald Ltd 92 Cavendish Nuclear Ltd 207 Denton Alyn & Deeside Rt Hon -

Local Electricity Bill

Local Electricity Bill A B I L L TO Enable electricity generators to become local electricity suppliers; and for connected purposes. 1 Purpose The purpose of this Act is to encourage and enable the local supply of electricity. 2 Local electricity suppliers (1) An electricity generator may be a local electricity supplier. (2) In this section “electricity generator” has the same meaning as in section 6 of the Electricity Act 1989. (3) A local supplier must – (a) hold a local electricity supply licence, and (b) adhere to the conditions of that local electricity supply licence. 3 Amendment of the Electricity Act 1989 (1) The Electricity Act 1989 is amended as follows. (2) In section 6 (licences authorising supply, etc.), after subsection (1)(d), insert – “(da) a licence authorising a person to supply electricity to premises within a designated local area (“a local electricity supply licence”); (3) After section 6 insert – “6ZA Local electricity supply licences (1) Subject to it exercising its other functions under this Act the Gas and Electricity Markets Authority (“the Authority”) may grant a local electricity supply licence to a person who meets local electricity supply licence conditions. (2) The Authority must set local electricity supply licence conditions. (3) The Authority must specify the designated local area for each local electricity supply licence. (4) Before making any specification under subsection (3) the Authority must consult – (a) any relevant local authority; (b) any existing local electricity suppliers; (c) any persons who have, to the knowledge of the Authority, expressed an interest in becoming local electricity suppliers; (d) any other person who, in its opinion, has an interest in that matter. -

Open PDF 284KB

Transport Committee Oral evidence: HS2: progress update, HC 487 Wednesday 14 July 2021, Birmingham Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 14 July 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Huw Merriman (Chair); Mr Ben Bradshaw; Ruth Cadbury; Simon Jupp; Robert Largan; Karl McCartney. Public Accounts Committee Members Present: Shaun Bailey and Sir Geoffrey Clifton-Brown. Questions 1 - 73 Witnesses I: Andy Street CBE, Mayor, West Midlands Combined Authority; and Mark Thurston, Chief Executive Officer, High Speed Two. Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Andy Street CBE and Mark Thurston. Q1 Chair: This is the Transport Select Committee’s six-month evidence session on the progress of HS2. We have two witnesses before us. Please introduce yourselves for the record. Perhaps we will start with the Mayor. Andy Street: I am Andy Street, the West Midlands Mayor. Mark Thurston: I am Mark Thurston, the Chief Executive of HS2 Limited. Q2 Chair: Andy and Mark, thank you very much for being with us. I should state, if it is not absolutely obvious, that we are not in Parliament but are in formal proceedings. We are delighted to be in Birmingham. When the Select Committee was formed after the new Parliament in 2019, we pledged that we would go out on the road, we would look at HS2 every six months and we would look at the line of the route. We have been unable to do that thus far but we are now free to do so and it is brilliant to be here in Birmingham. We are looking forward to going to see the Curzon Street site this afternoon and we have met with some of the business leads before you in an informal session. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 691 15 March 2021 No. 190 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 15 March 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. BORIS JOHNSON, MP, DECEMBER 2019) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY,MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE AND MINISTER FOR THE UNION— The Rt Hon. Boris Johnson, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Rishi Sunak, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN,COMMONWEALTH AND DEVELOPMENT AFFAIRS AND FIRST SECRETARY OF STATE— The Rt Hon. Dominic Raab, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Priti Patel, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. Michael Gove, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. Robert Buckland, QC, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Ben Wallace, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP COP26 PRESIDENT—The Rt Hon. Alok Sharma, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Kwasi Kwarteng, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE, AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Elizabeth Truss, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Dr Thérèse Coffey, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. -

UK Parliamentary Select Committees 2020 a Cicero/AMO Analysis Cicero/AMO / March 2020

/ UK Parliamentary Select Committees 2020 A Cicero/AMO Analysis Cicero/AMO / March 2020 / Cicero/AMO / 1 / / Contents Foreword 3 Treasury Select Committee 4 Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee 6 Committee on the Future Relationship with the European Union 8 International Trade Committee 10 Home Affairs Committee 12 Transport Committee 14 Environmental Audit Committee 16 About Cicero/AMO 19 Foreword After December’s General Election, the House of Commons Select Committees have now been reconstituted. Cicero/AMO is pleased to share with you our analysis of the key Select Committees, including a look at their Chairs, members, the ‘ones to watch’ and their likely priorities. Select Committees – made up of backbench MPs – are charged with scrutinising Government departments and specific policy areas. They have become an increasingly important part of the parliamentary infrastructure, and never more so than in the last Parliament, where the lack of Government majority and party splits over Brexit allowed Select Committees to provide an authoritative form of Government scrutiny. However, this new Parliament looks very different. The large majority afforded to Boris Johnson in the election and the resulting Labour leadership contest give rise to a number of questions over Select Committee influence. Will the Government take Select Committee recommendations seriously as they form policy, or – without the need to keep every backbencher on side - will they feel at liberty to disregard the input of Committees? Will the Labour Party regroup when a new Leader is in place and provide a more effective Opposition or will a long period of navel-gazing leave space for Select Committees to fill this void? While Select Committees’ ability to effectively keep Government in check remains unclear, they will still be able to influence the media narrative around their chosen areas of inquiry.