Levelling up Innovation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coronavirus Bill 23 March 2020 Volume 674 the Chairman of Ways

25/03/2020 Coronavirus Bill - Hansard Cookies: We use cookies to give you the best possible experience on our site. By continuing to use OK the site you agree to our use of cookies. Find out more Coronavirus Bill Share 23 March 2020 Volume 674 Proceedings resumed (Order, this day). Considered in Committee (Order, this day). [Dame Eleanor Laing in the Chair] The Chairman of Ways and Means (Dame Eleanor Laing) I have a few things to explain before we begin Committee stage. For understandable reasons, a large number of manuscript amendments have been tabled by the Government today, and in fact a large number of other manuscript amendments have, unusually, been allowed today as well. Members therefore need to make sure that they are working from the right version of the notice paper and that they have the latest version of the grouping and selection list, although I should explain that there is one group. Government amendments 79 to 82 on extradition are on a separate supplementary notice paper, and a revised grouping and selection list will be issued shortly. The late appearance of these amendments is due not to Government action but to a mistake on the part of the Public Bill Ofce, but, lest anybody complain, I will defend the Public Bill Ofce, because they have done a marvellous job today. I have seen it over the last few days, and the people who work here have worked miracles to get us to this stage in such good order. The Business of the House motion, which the House agreed before Second Reading, allows the Chair discretion at the end of the time allowed for Committee—in this case, that falls at exactly 10 pm—to call non-Government amendments and new clauses to be moved formally https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2020-03-23/debates/1BF3C655-EAD2-45DF-BAE2-30052908F7E6/CoronavirusBill 1/122 25/03/2020 Coronavirus Bill - Hansard at that stage for separate decision. -

Committee of the Whole House Proceedings

1 House of Commons Thursday 11 February 2021 COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE HOUSE PROCEEDINGS MINISTERIAL AND OTHER MATERNITY ALLOWANCES BILL GLOSSARY This document shows the fate of each clause, schedule, amendment and new clause. The following terms are used: Added: New Clause agreed without a vote and added to the Bill. Agreed to: agreed without a vote. Agreed to on division: agreed following a vote. Negatived: rejected without a vote. Negatived on division: rejected following a vote. Not called: debated in a group of amendments, but not put to a decision. Not moved: not debated or put to a decision. Question proposed: debate underway but not concluded. Withdrawn after debate: moved and debated but then withdrawn, so not put to a decision. Not selected: not chosen for debate by the Chair. Kirsten Oswald Negatived 3 Clause 1,page1, line 5, leave out “may” and insert “must” 2 Committee of the whole House Proceedings: 11 February 2021 Ministerial and Other Maternity Allowances Bill, continued Jackie Doyle-Price Sir John Hayes Ben Bradley Tonia Antoniazzi Rosie Duffield Cherilyn Mackrory Andrew Rosindell Fiona Bruce Stephen Metcalfe Bob Blackman Not called 15 Clause 1,page1, line 5, leave out “a person as” Jackie Doyle-Price Sir John Hayes Ben Bradley Tonia Antoniazzi Rosie Duffield Cherilyn Mackrory Andrew Rosindell Fiona Bruce Stephen Metcalfe Bob Blackman Not called 16 Clause 1,page1, line 14, leave out “person” and insert “minister” Sir John Hayes Miriam Cates Lee Anderson Alexander Stafford Ben Bradley Tom Hunt Sir Edward Leigh Karl McCartney -

Open PDF 290KB

Public Accounts Committee Oral evidence: Towns Fund, HC 651 Monday 21 September 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 21 September 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Meg Hillier (Chair); Kemi Badenoch; Olivia Blake; Sir Geoffrey Clifton-Brown; Peter Grant; Mr Richard Holden; Craig Mackinlay; Shabana Mahmood; Mr Gagan Mohindra; James Wild. Gareth Davies, Comptroller and Auditor General, National Audit Office, Lee Summerfield, Director, NAO, and David Fairbrother, Treasury Officer of Accounts, HM Treasury, were in attendance. Questions 1-111 Witnesses I: Jeremy Pocklington, Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, Emran Mian, Director General, MHCLG, and Stephen Jones, Co-Director, Cities and Local Growth Unit, MHCLG. Written evidence from witnesses: Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General Review of the Town Deals selection process (HC 576) Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Jeremy Pocklington, Emran Mian and Stephen Jones. Q1 Chair: Welcome to the Public Accounts Committee on Monday 21 September 2020. We are here today to look at the towns fund. Our thanks go to the National Audit Office, which has done a factual report on money that was allocated to towns, as defined by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. The money has not been allocated yet, but towns were identified to bid for a pot of funding to improve their area. I will introduce that more formally in a moment. We have a special opportunity today to welcome a member of our Committee who rarely attends because she is the Exchequer Secretary. Kemi Badenoch is a member of the Committee and also a Treasury Minister. -

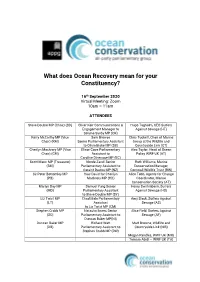

What Does Ocean Recovery Mean for Your Constituency?

What does Ocean Recovery mean for your Constituency? 16th September 2020 Virtual Meeting: Zoom 10am – 11am ATTENDEES Steve Double MP (Chair) (SD) Oliver Kerr Communications & Hugo Tagholm, CEO Surfers Engagement Manager to Against Sewage (HT) Selaine Saxby MP (OK) Kerry McCarthy MP (Vice Sam Browse Chris Tuckett, Chair of Marine Chair) (KM) Senior Parliamentary Assistant Group at the Wildlife and to Olivia Blake MP (SB) Countryside Link (CT) Cherilyn Mackrory MP (Vice Elinor Cope Parliamentary Alec Taylor, Head of Ocean Chair) (CM) Assistant to Policy WWF UK (AT) Caroline Dinenage MP (EC) Scott Mann MP (Treasurer) Nicole Zandi Senior Ruth Williams, Marine (SM) Parliamentary Assistant to Conservation Manager, Geraint Davies MP (NZ) Cornwall Wildlife Trust (RW) Sir Peter Bottomley MP Huw David for Cherilyn Alice Tebb, Agents for Change (PB) Mackrory MP (HD) Coordinator, Marine Conservation Society (AT) Martyn Day MP Samuel Yung Senior Henry Swithinbank, Surfers (MD) Parliamentary Assistant Against Sewage (HS) to Steve Double MP (SY) Liz Twist MP Chad Male Parliamentary Amy Slack, Surfers Against (LT) Assistant Sewage (AS) to Liz Twist MP (CM) Stephen Crabb MP Natasha Ikners Senior Alice Field, Surfers Against (SC) Parliamentary Assistant to Sewage (AF) Duncan Baker MP(NI) Duncan Baker MP Richard Watt Matt Browne, Wildlife and (DB) Parliamentary Assistant to Countryside Link (MB) Stephen Crabb MP (RW) Megan Randles, WWF UK (MR) Tamara Abidi – WWF UK (TA) MINUTES Welcome and Opening Remarks Steve Double MP, Chair of the APPG welcomed the attendees to the first ever digital Ocean Conservation APPG and set out the role of the group as the voice of the ocean in parliament. -

A Guide to the Government for BIA Members

A guide to the Government for BIA members Correct as of 26 June 2020 This is a briefing for BIA members on the Government led by Boris Johnson and key ministerial appointments for our sector after the December 2019 General Election and February 2020 Cabinet reshuffle. Following the Conservative Party’s compelling victory, the Government now holds a majority of 80 seats in the House of Commons. The life sciences sector is high on the Government’s agenda and Boris Johnson has pledged to make the UK “the leading global hub for life sciences after Brexit”. With its strong majority, the Government has the power to enact the policies supportive of the sector in the Conservatives 2019 Manifesto. All in all, this indicates a positive outlook for life sciences during this Government’s tenure. Contents: Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector .......................................................................................... 2 Ministers and policy maker profiles................................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector* *Please note that this guide only covers ministers and responsibilities relevant to the life sciences and will be updated as further roles and responsibilities are announced. Department Position Holder Relevant responsibility Holder in -

Uk Government and Special Advisers

UK GOVERNMENT AND SPECIAL ADVISERS April 2019 Housing Special Advisers Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under INTERNATIONAL 10 DOWNING Toby Lloyd Samuel Coates Secretary of State Secretary of State Secretary of State Secretary of State Deputy Chief Whip STREET DEVELOPMENT Foreign Affairs/Global Salma Shah Rt Hon Tobias Ellwood MP Kwasi Kwarteng MP Jackie Doyle-Price MP Jake Berry MP Christopher Pincher MP Prime Minister Britain James Hedgeland Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Secretary of State Chief Whip (Lords) Rt Hon Theresa May MP Ed de Minckwitz Olivia Robey Secretary of State INTERNATIONAL Parliamentary Under Secretary of State and Minister for Women Stuart Andrew MP TRADE Secretary of State Heather Wheeler MP and Equalities Rt Hon Lord Taylor Chief of Staff Government Relations Minister of State Baroness Blackwood Rt Hon Penny of Holbeach CBE for Immigration Secretary of State and Parliamentary Under Mordaunt MP Gavin Barwell Special Adviser JUSTICE Deputy Chief Whip (Lords) (Attends Cabinet) President of the Board Secretary of State Deputy Chief of Staff Olivia Oates WORK AND Earl of Courtown Rt Hon Caroline Nokes MP of Trade Rishi Sunak MP Special Advisers Legislative Affairs Secretary of State PENSIONS JoJo Penn Rt Hon Dr Liam Fox MP Parliamentary Under Laura Round Joe Moor and Lord Chancellor SCOTLAND OFFICE Communications Special Adviser Rt Hon David Gauke MP Secretary of State Secretary of State Lynn Davidson Business Liason Special Advisers Rt Hon Amber Rudd MP Lord Bourne of -

General Election 2019: Mps in Wales

Etholiad Cyffredinol 2019: Aelodau Seneddol yng Nghymru General Election 2019: MPs in Wales 1 Plaid Cymru (4) 5 6 Hywel Williams 2 Arfon 7 Liz Saville Roberts 2 10 Dwyfor Meirionnydd 3 4 Ben Lake 8 12 Ceredigion Jonathan Edwards 14 Dwyrain Caerfyrddin a Dinefwr / Carmarthen East and Dinefwr 9 10 Ceidwadwyr / Conservatives (14) Virginia Crosbie Fay Jones 1 Ynys Môn 13 Brycheiniog a Sir Faesyfed / Brecon and Radnorshire Robin Millar 3 Aberconwy Stephen Crabb 15 11 Preseli Sir Benfro / Preseli Pembrokeshire David Jones 4 Gorllewin Clwyd / Clwyd West Simon Hart 16 Gorllewin Caerfyrddin a De Sir Benfro / James Davies Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire 5 Dyffryn Clwyd / Vale of Clwyd David Davies Rob Roberts 25 6 Mynwy / Monmouth Delyn Jamie Wallis Sarah Atherton 33 8 Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr / Bridgend Wrecsam / Wrexham Alun Cairns 34 Simon Baynes Bro Morgannwg / Vale of Glamorgan 9 12 De Clwyd / Clwyd South 13 Craig Williams 11 Sir Drefaldwyn / Montgomeryshire 14 15 16 25 24 17 23 21 22 26 18 20 30 27 19 32 28 31 29 39 40 36 33 Llafur / Labour (22) 35 37 Mark Tami 38 7 34 Alyn & Deeside / Alun a Glannau Dyfrdwy Nia Griffith Gerald Jones 17 23 Llanelli Merthyr Tudful a Rhymni / Merthyr Tydfil & Rhymney Tonia Antoniazzi Nick Smith Chris Bryant 18 24 30 Gwyr / Gower Blaenau Gwent Rhondda Geraint Davies Nick Thomas-Symonds Chris Elmore Jo Stevens 19 26 31 37 Gorllewin Abertawe / Swansea West Tor-faen / Torfaen Ogwr / Ogmore Canol Caerdydd / Cardiff Central Carolyn Harris Chris Evans Stephen Kinnock Stephen Doughty 20 27 32 38 Dwyrain Abertawe / -

View Future Day Orals PDF File 0.11 MB

Published: Friday 4 December 2020 Questions for oral answer on a future day (Future Day Orals) Questions for oral answer on a future day as of Friday 4 December 2020. The order of these questions may be varied in the published call lists. [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Monday 7 December Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Defence Allan Dorans (Ayr, Carrick and Cumnock): What plans he has for future military and security co-operation with EU (a) institutions and (b) member states. (909779) Jessica Morden (Newport East): What steps he is taking to increase the take-up of UK-produced steel in defence procurement. (909780) Sir David Amess (Southend West): What steps he is taking to ensure that his Department’s spending supports (a) high-skilled jobs and (b) the wider UK economy. (909781) Fleur Anderson (Putney): What support his Department has provided to veterans during the covid-19 outbreak. (909782) Holly Mumby-Croft (Scunthorpe): What recent preparations his Department has made to support (a) the NHS and (b) other public bodies in their response to the covid-19 outbreak. (909783) David Simmonds (Ruislip, Northwood and Pinner): What recent preparations his Department has made to support (a) the NHS and (b) other public bodies in their response to the covid-19 outbreak. (909784) Christine Jardine (Edinburgh West): What recent assessment he has made of the effectiveness of his Department's official development assistance spending. (909785) Andrew Jones (Harrogate and Knaresborough): What recent assessment he has made of the potential merits of including armed forces veterans in the UK’s response to the covid-19 outbreak. -

MIDLANDS MATTERS ISSUE 3 Midlandsengine.Org

MIDLANDS MATTERS ISSUE 3 midlandsengine.org Welcome to an earlier than planned third to adjust, try to keep fit and healthy and establish edition of our partnership newsletter, a new work-life balance. Midlands Matters. And with so many simply extraordinary We are living through unprecedented times - responses from partner organisations right and Covid-19 is a challenge to us all, on both across Midlands Engine, on work to combat the individual and organisational levels. I would like virus in a medical and clinical setting - I wanted to take this opportunity to personally send you to share with you the remarkable work of those my very best wishes, and hope that you, your teams involved here too. From donating supplies colleagues and your families are well and remain of personal protective equipment, to producing so in coming weeks. hand sanitiser on an industrial scale, helping DNA sequencing of the virus and providing But there are positives we can find in this testing kits, the Midlands has truly delivered situation - and the early issue of this newsletter when called upon - and will continue to do so. is here to recognise the phenomenal work that is going on in our partnership on a day- I hope this positive news bring a small reprieve by-day basis to help with the fight against to the heavy workloads we are all carrying Covid-19. Partners across the region have been right now, and serves as an uplifting reminder contributing to the cause in all manner of ways that there is great work going on to defeat the and I wanted to share just some of these stories virus. -

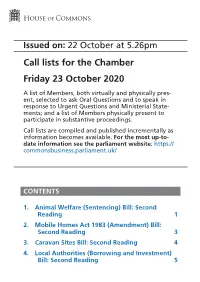

(Amendment) Bill: Second Reading 3 3

Issued on: 22 October at 5.26pm Call lists for the Chamber Friday 23 October 2020 A list of Members, both virtually and physically pres- ent, selected to ask Oral Questions and to speak in response to Urgent Questions and Ministerial State- ments; and a list of Members physically present to participate in substantive proceedings. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to- date information see the parliament website: https:// commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. Animal Welfare (Sentencing) Bill: Second Reading 1 2. Mobile Homes Act 1983 (Amendment) Bill: Second Reading 3 3. Caravan Sites Bill: Second Reading 4 4. Local Authorities (Borrowing and Investment) Bill: Second Reading 5 2 Call lists for the Chamber Friday 23 October 2020 ANIMAL WELFARE (SENTENCING) BILL: SECOND READING Debate on the Second Reading of the Animal Welfare (Sentencing) Bill is expected to start at 9.35am and may not continue after 2.30pm. It is expected to conclude at about 1.45pm. Order Member Debate Party 1 Chris Loder (West Animal Welfare (Sentenc- Con Dorset) ing) Bill: Second Reading 2 Kerry McCarthy (Bristol Animal Welfare (Sentenc- Lab East) ing) Bill: Second Reading 3 Neil Parish (Tiverton and Animal Welfare (Sentenc- Con Honiton) ing) Bill: Second Reading 4 Sir Christopher Chope Animal Welfare (Sentenc- Con (Christchurch) ing) Bill: Second Reading 5 Mark Jenkinson (Work- Animal Welfare (Sentenc- Con ington) ing) Bill: Second Reading 6 Sir David Amess (Sou- Animal Welfare (Sentenc- Con thend -

Daily Report Thursday, 14 January 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 14 January 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 14 January 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:29 P.M., 14 January 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 7 Police and Crime BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Commissioners: Elections 15 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 7 Schools: Procurement 16 Additional Restrictions Grant 7 Veterans: Suicide 16 Business: Coronavirus 7 DEFENCE 17 Business: Grants 8 Armed Forces: Health Conditions of Employment: Services 17 Re-employment 9 Defence: Expenditure 17 Industrial Health and Safety: HMS Montrose: Repairs and Coronavirus 9 Maintenance 18 Motor Neurone Disease: HMS Queen Elizabeth: Research 10 Repairs and Maintenance 18 Podiatry: Coronavirus 11 DIGITAL, CULTURE, MEDIA AND Public Houses: Coronavirus 11 SPORT 19 Wind Power 12 British Telecom: Disclosure of Information 19 CABINET OFFICE 13 Broadband: Elmet and Civil Servants: Business Rothwell 20 Interests 13 Broadband: Greater London 20 Coronavirus: Disease Control 13 Chatterley Whitfield Colliery 21 Coronavirus: Lung Diseases 13 Data Protection 22 Debts 14 Educational Broadcasting: Fisheries: UK Relations with Coronavirus 23 EU 14 Events Industry and Iron and Steel: Procurement 14 Performing Arts: Greater National Security Council: London 23 Coronavirus 15 Football: Dementia 24 Football: Gambling 24 Organic Food: UK Trade with Freedom of Expression -

RAIL NEEDS ASSESSMENT for the MIDLANDS and the NORTH Final Report

RAIL NEEDS ASSESSMENT FOR THE MIDLANDS AND THE NORTH Final report December 2020 National Infrastructure Commission | Rail Needs Assessment for the Midlands and the North - Final report Contents The Commission 3 Foreword 5 Infographic 7 In brief 8 Executive summary 9 1.Background 21 2. Rail and economic outcomes in the Midlands and the North 24 3. A core pipeline and an adaptive approach 35 4. Developing packages of rail investments 39 5. Comparison of packages 51 6. Long term commitments and shorter term wins 64 Annex A. The package focussing on upgrades 72 Annex B. The package prioritising regional links 78 Annex C. The package prioritising long distance links 86 Acknowledgements 94 Endnotes 97 2 National Infrastructure Commission | Rail Needs Assessment for the Midlands and the North - Final report The Commission The Commission’s remit The Commission provides the government with impartial, expert advice on major long term infrastructure challenges. Its remit covers all sectors of economic infrastructure: energy, transport, water and wastewater (drainage and sewerage), waste, flood risk management and digital communications. While the Commission considers the potential interactions between its infrastructure recommendations and housing supply, housing itself is not in its remit. Also, out of the scope of the Commission are social infrastructure, such as schools, hospitals or prisons, agriculture, and land use. The Commission’s objectives are to support sustainable economic growth across all regions of the UK, improve competitiveness,