Johannes Brahms (1897-1833)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOHANNES BRAHMS: CLASSICAL INCLINATIONS in a ROMANTIC AGE a Series of Fourteen Recitals with Pianist Ian Hobson and Colleagues

JOHANNES BRAHMS: CLASSICAL INCLINATIONS IN A ROMANTIC AGE A series of fourteen recitals with pianist Ian Hobson and colleagues 1. Tuesday, September 10, 2013, 7:30 p.m., Benzaquen Hall Brahms: Scherzo in E flat minor, Op. 4 Ian Hobson, piano Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann, Op. 23 for piano four hands Ian Hobson, piano, Claude Hobson, piano ----------- Brahms : Piano Sonata No. 1 in C major, Op. 1 Ian Hobson, piano 2. Thursday, September 12, 2013, 7:30 p.m., Benzaquen Hall Brahms: Piano Sonata No. 2 in F sharp minor, Op. 2 Ian Hobson, piano Hungarian Dances, Book 1: Nos. 1 – 5 arranged for solo piano Ian Hobson, piano ----------- Brahms: Hungarian Dances, Book 2: Nos. 6 – 10 arranged for solo piano Ian Hobson, piano Hungarian Dances, Book 3-4: Nos. 11 – 21 for piano four hands Ian Hobson, piano, Edward Rath, piano 3. Tuesday, September 24, 2013, 7:30 p.m.,Benzaquen Hall J.S.Bach/Brahms: Chaconne in D minor arranged for piano left hand Ian Hobson, piano Brahms: Zigeunerlieder, Op. 103, arranged by Theodor Kirchner for piano four hands Ian Hobson, piano, Samir Golescu, piano ---------- Brahms : Theme and Variations in D minor arranged for piano from the B flat sextet for strings, Op. 18 Ian Hobson, piano J.S.Bach/Brahms: Presto in G minor arranged for piano (two versions) Ian Hobson, piano Brahms: Six Baroque Movements Ian Hobson, piano Brahms: Three Little Pieces Ian Hobson, piano Brahms: Five Arrangements Ian Hobson, piano 4. Thursday, September 26, 2013, 7 :30 p.m., Cary Hall Brahms: Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann, Op. -

Download Program Notes

Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 Johannes Brahms ohannes Brahms was 29 years old in 1862, seated at the other piano. Ironically, critics Jwhen he embarked on this seminal mas- now complained that the work lacked the terpiece of the chamber-music repertoire, sort of warmth that string instruments would though the work would not reach its final have provided — the opposite of Joachim’s form as his Piano Quintet until two years objection. Unlike the original string-quintet later. He was no beginner in chamber music version, which Brahms burned, the piano when he began this project. He had already duet was published — and is still performed written dozens of ensemble works before and appreciated — as his Op. 34bis. he dared to publish one, his B-major Piano By this time, however, Brahms must have Trio (Op. 8) of 1853–54. Among those early, grown convinced of the musical merits of his unpublished chamber pieces were 20-odd material and, with some coaxing from his string quartets, all of which he consigned friend Clara Schumann, he gave the piece to destruction prior to finally publishing his one more try, incorporating the most idiom- three mature works in that classic genre in atic aspects of both versions. The resulting the 1870s. In truth, he did get some use out Piano Quintet, the composer’s only essay of those early quartets — to paper the walls in that genre (and no wonder, after all that and ceilings of his apartment. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 42,1922

PARSONS THEATRE . ,. HARTFORD Monday Evening, November 27, at 8.15 .-# BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHCSTRS INC. FORTY-SECOND SEASON J922-J923 wW PRSGRsnnc 1 vg LOCAL MANAGEMENT, SEDGWICK & CASEY Steinway & Sons STEINERT JEWETT WOODBURY «. PIANOS w Duo-Art REPRODUCING PIANOS AND PIANOLA PIANOS VICTROLAS VICTOR RECORDS M, STEINERT & SONS 183 CHURCH STREET NEW HAVEN PARSONS THEATRE HARTFORD FORTY-SECOND SEASON 1922-1923 INC. PIERRE MONTEUX, Conductor MONDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 27, at 8.15 WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1922, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. FREDERICK P. CABOT President GALEN L. STONE Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE Treasurer ALFRED L. AIKEN ARTHUR LYMAN FREDERICK P. CABOT HENRY B. SAWYER ERNEST B. DANE GALEN L. STONE M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE BENTLEY W. WARREN JOHN ELLERTON LODGE E. SOHIER WELCH W. H. BRENNAN, Manager G. E. JUDD, Assistant Manager *UHE INSTRUMENT OF THE IMMORTALS QOMETIMES people who want a Steinway think it economi- cal to buy a cheaper piano in the beginning and wait for a Steinway. Usually this is because they do not realize with what ease Franz Liszt at his Steinway and convenience a Steinway can be bought. This is evidenced by the great number of people who come to exchange some other piano in partial payment for a Steinway, and say: "If I had only known about your terms I would have had a Steinway long ago!" You may purchase a new Steinway piano with a cash deposit of 10%, and the bal- ance will be extended over a period of two years. -

The Role of Clarinet in Op. 114 a Minor Trio Composed by Johannes Brahms for Clarinet, Cello and Piano

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.7, No. 3, pp.80-90, March 2019 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) THE ROLE OF CLARINET IN OP. 114 A MINOR TRIO COMPOSED BY JOHANNES BRAHMS FOR CLARINET, CELLO AND PIANO *İlkay Ak Lecturer, Music Department, Anadolu University, Eskişehir, Turkey ABSTRACT: Sonatas and chamber music works written for clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld by Johannes Brahms, who was one of the most important composers of the second half of Romantic period, in the last years of his life are among the irreplaceable works of clarinet training repertoire. These works which enable the musical improvement for the player are also significant to transfer the stylistic properties of the time. Op. 114 A Minor Trio composed for Clarinet, Cello and Piano by Brahms is among the most important works of chamber music training repertoire and often appears in concerts. The work consists of four parts. The first part is Allegro, the second part is Adagio, the third one is Andantino grazioso and the fourth one is Allegro. In this study, the life and musical identity of Brahms are going to be discussed first and then solo and chamber music works with clarinet are going to be mentioned. Next, the parts which can create technical and musical difficulties for the clarinet performance in Op. 114 A Minor Trio of the composer are determined and the things to decrease these are going to be suggested. KEYWORDS: Romantic Period, Brahms, Mühlfeld, Clarinet, Trio INTRODUCTION: JOHANNES BRAHMS Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) German Johannes Brahms as one of the prominent composers of the second half of 19th century was born on 7 May 1833 as a son of a double bass player. -

The Virtuoso Johann Strauss

The Virtuoso Johann Strauss Thomas Labé, Piano CD CONTENTS 1. Carnaval de Vienne/Moriz Rosenthal 2. Wahlstimmen/Karl Tausig 3. Symphonic Metamorphosis of Wein, Weib und Gesang (Wine, Woman and Song)/Leopold Godowsky 4. Man lebt nur einmal (One Lives but Once)/Karl Tausig 5. Symphonic Metamorphosis of Die Fledermaus/Leopold Godowsky 6. Valse-Caprice in A Major (Op. Posth.)/Karl Tausig 7. Nachtfalter (The Moth)/Karl Tausig 8. Arabesques on By the Beautiful Blue Danube/Adolf Schulz-Evler LINER NOTES At the end of Johann Strauss’ 1875 operetta Die Fledermaus, all of the characters drink a toast to the real culprit of the story—“Champagner hat's verschuldet”—a fitting conclusion to the most renowned and potent evocation of the carefree life of post-revolution imperial Vienna. Strauss' sparkling score (never mind that the libretto is an amalgam of German and French sources), infused with that most famous of Viennese dances, the waltz, lent eloquent expression to the transitory atmosphere of confidence and prosperity induced by the Hapsburg monarchs. “The Emporer Franz Joseph I,” it would later be said, "only reigned until the death of Johann Strauss." And what could have provided more perfect source material than the music of Strauss, for the pastiche creations of the illustrious composer-pianists who roamed the world in the latter 19th and early 20th centuries, forever seeking vehicles with which to exploit the possibilities of their instrument and display their pianistic prowess? This disc presents a succession of such indulgent enterprises, all fashioned from Strauss’ music, for four notable composer-pianists: Moriz Rosenthal, Karl Tausig, Leopold Godowsky, and Adolf Schulz-Evler. -

Chopin: the Man and His Music 1 Chopin: the Man and His Music

Chopin: The Man and His Music 1 Chopin: The Man and His Music Project Gutenberg's Chopin: The Man and His Music, by James Huneker Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Chopin: The Man and His Music Author: James Huneker Release Date: Jan, 2004 [EBook #4939] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on April 1, 2002] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CHOPIN: THE MAN AND HIS MUSIC *** This ebook was produced by John Mamoun <[email protected]> with help from Charles Franks and the Online Distributed Proofreaders website. CHOPIN: THE MAN AND HIS MUSIC TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I.--THE MAN. I. POLAND:--YOUTHFUL IDEALS II. -

Guide to Repertoire

Guide to Repertoire The chamber music repertoire is both wonderful and almost endless. Some have better grips on it than others, but all who are responsible for what the public hears need to know the landscape of the art form in an overall way, with at least a basic awareness of its details. At the end of the day, it is the music itself that is the substance of the work of both the performer and presenter. Knowing the basics of the repertoire will empower anyone who presents concerts. Here is a run-down of the meat-and-potatoes of the chamber literature, organized by instrumentation, with some historical context. Chamber music ensembles can be most simple divided into five groups: those with piano, those with strings, wind ensembles, mixed ensembles (winds plus strings and sometimes piano), and piano ensembles. Note: The listings below barely scratch the surface of repertoire available for all types of ensembles. The Major Ensembles with Piano The Duo Sonata (piano with one violin, viola, cello or wind instrument) Duo repertoire is generally categorized as either a true duo sonata (solo instrument and piano are equal partners) or as a soloist and accompanist ensemble. For our purposes here we are only discussing the former. Duo sonatas have existed since the Baroque era, and Johann Sebastian Bach has many examples, all with “continuo” accompaniment that comprises full partnership. His violin sonatas, especially, are treasures, and can be performed equally effectively with harpsichord, fortepiano or modern piano. Haydn continued to develop the genre; Mozart wrote an enormous number of violin sonatas (mostly for himself to play as he was a professional-level violinist as well). -

Naxos Catalog (May

CONTENTS Foreword by Klaus Heymann . 3 Alphabetical List of Works by Composer . 5 Collections . 95 Alphorn 96 Easy Listening 113 Operetta 125 American Classics 96 Flute 116 Orchestral 125 American Jewish Music 96 Funeral Music 117 Organ 128 Ballet 96 Glass Harmonica 117 Piano 129 Baroque 97 Guitar 117 Russian 131 Bassoon 98 Gypsy 119 Samplers 131 Best Of series 98 Harp 119 Saxophone 132 British Music 101 Harpsichord 120 Timpani 132 Cello 101 Horn 120 Trombone 132 Chamber Music 102 Light Classics 120 Tuba 133 Chill With 102 Lute 121 Trumpet 133 Christmas 103 Music for Meditation 121 Viennese 133 Cinema Classics 105 Oboe 121 Violin 133 Clarinet 109 Ondes Martenot 122 Vocal and Choral 134 Early Music 109 Operatic 122 Wedding Music 137 Wind 137 Naxos Historical . 138 Naxos Nostalgia . 152 Naxos Jazz Legends . 154 Naxos Musicals . 156 Naxos Blues Legends . 156 Naxos Folk Legends . 156 Naxos Gospel Legends . 156 Naxos Jazz . 157 Naxos World . 158 Naxos Educational . 158 Naxos Super Audio CD . 159 Naxos DVD Audio . 160 Naxos DVD . 160 List of Naxos Distributors . 161 Naxos Website: www.naxos.com Symbols used in this catalogue # New release not listed in 2005 Catalogue $ Recording scheduled to be released before 31 March, 2006 † Please note that not all titles are available in all territories. Check with your local distributor for availability. 2 Also available on Mini-Disc (MD)(7.XXXXXX) Reviews and Ratings Over the years, Naxos recordings have received outstanding critical acclaim in virtually every specialized and general-interest publication around the world. In this catalogue we are only listing ratings which summarize a more detailed review in a single number or a single rating. -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito. -

Schumann Piano Quartet Brahms Piano Quintet

BIS-2258 From left: Yevgeny Sudbin, Hrachya Avanesyan Alexander Chaushian, Diemut Poppen, Boris Brovtsyn SCHUMANN Hrachya Avanesyan PIANO QUARTET in E flat major, Op. 47 Boris Brovtsyn Diemut Poppen BRAHMS PIANO QUINTET Alexander Chaushian in F minor, Op. 34 Yevgeny Sudbin SCHUMANN, Robert (1810–56) Quartet for piano, violin, viola and cello 25'27 Op.47 (1842) 1 I. Sostenuto assai — Allegro ma non troppo 8'36 2 II. Scherzo. Molto vivace 3'16 3 III. Andante cantabile 5'59 4 IV. Finale. Vivace 7'29 BRAHMS, Johannes (1833–97) Quintet for piano, 2 violins, viola and cello 38'21 Op.34 (1864) 5 I. Allegro non troppo 13'45 6 II. Andante, un poco Adagio 7'31 7 III. Scherzo. Allegro – Trio 6'45 8 IV. Finale. Poco sostenuto—Allegro non troppo – Presto non troppo 10'01 TT: 64'32 Yevgeny Sudbin piano Hrachya Avanesyan violin (Schumann) / violin II (Brahms) Boris Brovtsyn violin I (Brahms) Diemut Poppen viola Alexander Chaushian cello 2 obert Schumann tackled the piano quartet genre on several occa sions – in 1828–29 he composed a piano quintet in C minor (which has survived R only in fragmentary form) for the Leipzig ‘quartet entertainments’ that he had founded, and in 1831–32 he wrote a few bars of a piano quartet in B major – but it was only the Piano Quartet in E flat major, Op. 47, from the ‘chamber music year’ of 1842, that was included in his official catalogue of works. Schumann com- posed it in October and November 1842, immediately after finishing his Piano Quin tet in the same key, Op. -

Brahms Clarinet Sonata Op 120 No 1

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Clarinet Sonata in F minor Op 120 No 1 (1894) Allegro appassionato Andante, un poco Adagio Allegretto grazioso Vivace By March 1891 Brahms' creative impetus appeared to have faded away. He had composed nothing for more than a year; he had completed his will. But then, when Brahms was visiting Meiningen, the conductor of the court orchestra drew his attention to the playing of their erstwhile violinist, now director of the court theatre and principal clarinettist Richard Mühlfeld (1856-1907), who performed privately for Brahms. As the clarinettist Anton Stadler had previously inspired Mozart, so now Mühlfeld inspired Brahms. There rapidly followed four wonderful chamber pieces: a Trio Op 114 and a Quintet Op 115 for clarinet and strings, and two clarinet and piano Sonatas Op 120 (also loved by viola players). In the hundred years since Mozart wrote his clarinet quintet, the instrument had evolved into something akin to the modern “Boehm” clarinet. Its larger number of keys, and consequently simpler fingering, made rapid chromatic playing easier than was possible on the much simpler clarinets used, albeit to great effect, by Stadler. Brahms is said to have particularly enjoyed the sound of clarinet with piano and in the two Op 120 sonatas he produces a wonderful richness of sound from the combination of the two instruments. Although the first movement is marked appassionata, and Brahms' earlier use of F minor had been turbulent (as in the Piano Quintet Op 34), the mood here is more lyrical and wistful, occasionally ‘smouldering rather than explosive' (Ivor Keys ). -

Liner Notes by Patrick Castillo and Andrew Goldstein

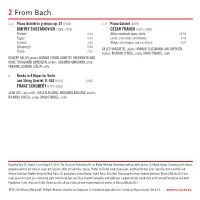

2 From Bach 1–5 Piano Quintet in g minor, op. 57 (1940) 7–9 Piano Quintet (1879) DMITRY SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975) CÉSAR FRANCK (1822–1890) Prelude 4:34 Molto moderato quasi lento 14:50 Fugue 9:33 Lento, con molto sentimento 9:49 Scherzo 3:25 Allegro non troppo, ma con fuoco 8:57 Intermezzo 5:50 GILLES VONSATTEL, piano; ARNAUD SUSSMANN, IAN SWENSEN, Finale 7:22 violins; RICHARD O’NEILL, viola; DAVID FINCKEL, cello GILBERT KALISH, piano; DANISH STRING QUARTET: FREDERIK ØLAND, RUNE TONSGAARD SØRENSEN, violins; ASBJØRN NØRGAARD, viola; FREDRIK SCHØYEN SJÖLIN, cello 6 Rondo in A Major for Violin and String Quartet, D. 438 (1816) 14:01 FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797–1828) SEAN LEE, solo violin; JORJA FLEEZANIS, BENJAMIN BEILMAN, violins; RICHARD O’NEILL, viola; DAVID FINCKEL, cello Recorded July 21, August 3, and August 9, 2013, The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton. Recording producer and engineer: Da-Hong Seetoo. Steinway grand pianos provided courtesy of ProPiano. Cover art: Imprint, 2006, by Sebastian Spreng. Photos by Tristan Cook, Diana Lake, and Brian Benton. Liner notes by Patrick Castillo and Andrew Goldstein. Booklet design by Nick Stone. CD production: Jerome Bunke, Digital Force, New York. Production Assistant: Andrew Goldstein. Music@Menlo 2013 was made possible in part by a leadership grant from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation with additional support from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and Koret Foundation Funds. American Public Media was the official radio and new-media broadcast partner of Music@Menlo 2013. © 2013 Music@Menlo LIVE. All Rights Reserved. Unauthorized Duplication Is a Violation of Applicable Laws.