CHAPTER 6. Terrestrial Fauna of the NBNERR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

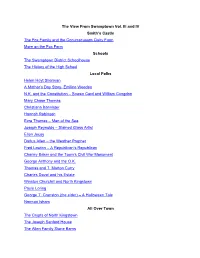

The View from Swamptown Vol

The View From Swamptown Vol. III and IV Smith’s Castle The Fox Family and the Cocumscussoc Dairy Farm More on the Fox Farm Schools The Swamptown District Schoolhouse The History of the High School Local Folks Helen Hoyt Sherman A Mother’s Day Story- Emiline Weeden N.K. and the Constitution – Bowen Card and William Congdon Mary Chase Thomas Christiana Bannister Hannah Robinson Ezra Thomas – Man of the Sea Joseph Reynolds – Stained Glass Artist Ellen Jecoy Darius Allen – the Weather Prophet Fred Lawton – A Republican’s Republican Charley Baker and the Town’s Civil War Monument George Anthony and the O.K. Thomas and T. Morton Curry Charles Davol and his Estate Winston Churchill and North Kingstown Paule Loring George T. Cranston (the elder) – A Halloween Tale Norman Isham All Over Town The Crypts of North Kingstown The Joseph Sanford House The Allen Family Stone Barns The Boston Post Cane Blacksmithing and Bootscrapers N.K. and the 1918 Spanish Influenza The Peach Pit and WWI Out of Town The Pettasquamscutt Rock Opinion Pieces Christmas 1964 – a child’s perspective Halloween – a child’s perspective The Origin of Some Well-known Phrases Reflections on Negro Cloth, N.K. and Slavery The 2002 Five Most Endangered Sites The 2003 Five Most Endangered Sites A Preservation Project Update A Kid Loves His Dog – Dog’s in Local History Return to main Table of Contents Return to North Kingstown Free Library The View From Swamptown by G. Timothy Cranston The Fox Family and The Cocumscussoc Dairy Farm I expect that when most of us think about Smith's Castle, the vision that comes to mind is one of colonial folks living in a fine blockhouse, or maybe a scene which includes soldiers mustering into formation, ready to march off into the Great Swamp and ultimately into the history books. -

Lepidoptera of North America 5

Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera by Valerio Albu, 1411 E. Sweetbriar Drive Fresno, CA 93720 and Eric Metzler, 1241 Kildale Square North Columbus, OH 43229 April 30, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration: Blueberry Sphinx (Paonias astylus (Drury)], an eastern endemic. Photo by Valeriu Albu. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Abstract A list of 1531 species ofLepidoptera is presented, collected over 15 years (1988 to 2002), in eleven southern West Virginia counties. A variety of collecting methods was used, including netting, light attracting, light trapping and pheromone trapping. The specimens were identified by the currently available pictorial sources and determination keys. Many were also sent to specialists for confirmation or identification. The majority of the data was from Kanawha County, reflecting the area of more intensive sampling effort by the senior author. This imbalance of data between Kanawha County and other counties should even out with further sampling of the area. Key Words: Appalachian Mountains, -

Rare Native Animals of RI

RARE NATIVE ANIMALS OF RHODE ISLAND Revised: March, 2006 ABOUT THIS LIST The list is divided by vertebrates and invertebrates and is arranged taxonomically according to the recognized authority cited before each group. Appropriate synonomy is included where names have changed since publication of the cited authority. The Natural Heritage Program's Rare Native Plants of Rhode Island includes an estimate of the number of "extant populations" for each listed plant species, a figure which has been helpful in assessing the health of each species. Because animals are mobile, some exhibiting annual long-distance migrations, it is not possible to derive a population index that can be applied to all animal groups. The status assigned to each species (see definitions below) provides some indication of its range, relative abundance, and vulnerability to decline. More specific and pertinent data is available from the Natural Heritage Program, the Rhode Island Endangered Species Program, and the Rhode Island Natural History Survey. STATUS. The status of each species is designated by letter codes as defined: (FE) Federally Endangered (7 species currently listed) (FT) Federally Threatened (2 species currently listed) (SE) State Endangered Native species in imminent danger of extirpation from Rhode Island. These taxa may meet one or more of the following criteria: 1. Formerly considered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for Federal listing as endangered or threatened. 2. Known from an estimated 1-2 total populations in the state. 3. Apparently globally rare or threatened; estimated at 100 or fewer populations range-wide. Animals listed as State Endangered are protected under the provisions of the Rhode Island State Endangered Species Act, Title 20 of the General Laws of the State of Rhode Island. -

A Fisherman-Scientist Collaboration to Re-Assess Lobster Nurseries in Narragansett Bay After Two Decades of Environmental Change

A Fisherman‐Scientist Collaboration to Project objectives: (1) Repeat a comprehensive diver‐based visual and suction sampling survey of Re‐assess Lobster Nurseries in lobster nurseries in Narragansett Bay and Rhode Island’s outer coast that had Narragansett Bay After Two Decades of been conducted by the same method in 1990 during a time of historically hig h lbtlobster abdbundance. Environmental Change (2) Deploy passive cobble‐filled post‐larval collectors at the same sites, thereby enabling side‐by‐side comparisons of the two methods. Richard Wahle (UMaine School of Marine Sciences), (3) Expand the survey using both methods to locations selected by the fishing Lanny Dellinger (RI Lobstermen’s Association) , industry. Undertake a hydrographic survey of mid‐summer conditions at the Scott Olszewski (RI Division of Fish and Wildlife) surface and bottom within lobster nursery habitat. 1990 2011 2012 2011 2012 Figure 1. Lobster densities (n/m2) and size composition from diver‐based visual quadrat surveys in 1990, 2011, 2012. 6 6 1990 Figure 3. Lobster densities (n/m2) and 2011 Collectors 2012 Collectors 20 2011 20 2012 4 4 20 size composition from passive collectors Frequency 2 Frequency 2 quency 10 10 10 (above) deployed in 2011 and 2012. Red ee N = 182 N = 60 Fr N =25 symbols denote young‐of‐year, and blue 0 0 0 0 0 1‐year‐old lobsters. 0 102030405060708090100 0 102030405060708090100 0 102030405060708090100 0 102030405060708090100 0 102030405060708090100 Carapace Length (mm) Carapace Length (mm) Carapace length (mm) Dissolved Salinity (psu) Te mpe r atur e (oC) pH Oxygen (mg L‐1) 1990 2011 2012 28 29 30 31 32 10 15 20 25 30 468107.6 7.8 8 8.2 Popasquash Surface Surface Mt. -

Prudence Island Narragansett Bay Research Reserve

Last Updated 1/20/07 Prudence Island Narragansett Bay Research Reserve Background Prudence Island is located in the geographic center of Narragansett Bay. The island is approximately 7 miles long and 1 mile across at its widest point. Located at the south end of the island is the Narragansett Bay Research Reserve’s Lab & Learning Center. The Center contains educational exhibits, a public meeting area, library, and research labs for staff and visiting scientists. The Reserve manages approximately 60% of Prudence; the largest components are at the north and south ends of Prudence Island. The vegetation on Prudence reflects the extensive farming that took place in the area until the early 1900s. After the fields were abandoned, woody plants gradually replaced the herbaceous species. The uplands are now covered with a dense shrub growth of bayberry, blueberry, arrowwood, and shadbush interspersed with red cedar, red maple, black cherry, pitch pine and oak. Green briar and Asiatic bittersweet cover much of the island as well. Prudence Island also supports one of the most dense white-tailed deer herds in New England . Raccoons, squirrels, Eastern red fox, Eastern cottontail rabbits, mink, and white-footed mice are plentiful. The large, salt marshes at the north end of Prudence are used as feeding areas by a number of large wading birds such as great and little blue herons, snowy and great egrets, black-crowned night herons, green-backed herons and glossy ibis. Between September and May, Prudence Island is also used as a haul-out site for harbor seals. History of Prudence Island Before colonial times, Prudence and the surrounding islands were under the control of the Narragansett Native Americans. -

Patience Island Narragansett Bay Research Reserve

Last Updated 1/20/07 Patience Island Narragansett Bay Research Reserve Background This 207-acre island lies to the west of northern Prudence Island. At their closest, the two islands are only 900 feet apart. The Patience Island is dominated by tall shrubs interspersed with red cedar and black cherry. Common shrubs include bayberry, highbush blueberry, and shadbush. Much of the island is also covered by brier, Asiatic bittersweet and poison ivy. A deciduous forest is gradually replacing the shrub habitat in some parts of the island. The small salt marsh on the southeastern shore provides habitat for seablite, a plant species common in other areas of the country, but rare in Rhode Island. The upland area of Patience Island supports a variety of wildlife including white-tailed deer, red fox, and Eastern cottontail rabbits. Coastal areas are used extensively by migrant and wintering waterfowl species such as horned grebes, greater scaup, black ducks and scoters. Quahogs are abundant in the sandy sediment. There is no ferry service available to this island. Visitors are welcome but you must provide your own transportation. Be aware that there is a high population of ticks, the trails may be overgrown, and camping is not permitted. History of Patience Island Historically, the Patience Island Farm covered an area of approximately 200 acres, nearly the entire island, and was a working farm as early as the mid-seventeenth century. The farm buildings were burned by the British during the Revolutionary War. After the war, the buildings were rebuilt and the farm remained in operation until the early twentieth century. -

The History and Future of Narragansett Bay

The History and Future of Narragansett Bay Capers Jones Universal Publishers Boca Raton, Florida USA • 2006 The History and Future of Narragansett Bay Copyright © 2006 Capers Jones All rights reserved. Universal Publishers Boca Raton , Florida USA • 2006 ISBN: 1-58112-911-4 Universal-Publishers.com Table of Contents Preface ...............................................................................................................................ix Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................... xiii Introduction..................................................................................................................... 15 Chapter 1 Geological Origins of Narragansett Bay.................................................................... 17 Defining Narragansett Bay ........................................................................................ 22 The Islands of Narragansett Bay............................................................................... 23 Earthquakes & Sea Level Changes of Narragansett Bay....................................... 24 Hurricanes & Nor’easters beside Narragansett Bay .............................................. 25 Meteorology of Hurricanes........................................................................................ 26 Meteorology of Nor’easters ....................................................................................... 27 Summary of Bay History........................................................................................... -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

City of Newport Comprehensive Harbor Management Plan

Updated 1/13/10 hk Version 4.4 City of Newport Comprehensive Harbor Management Plan The Newport Waterfront Commission Prepared by the Harbor Management Plan Committee (A subcommittee of the Newport Waterfront Commission) Version 1 “November 2001” -Is the original HMP as presented by the HMP Committee Version 2 “January 2003” -Is the original HMP after review by the Newport . Waterfront Commission with the inclusion of their Appendix K - Additions/Subtractions/Corrections and first CRMC Recommended Additions/Subtractions/Corrections (inclusion of App. K not 100% complete) -This copy adopted by the Newport City Council -This copy received first “Consistency” review by CRMC Version 3.0 “April 2005” -This copy is being reworked for clerical errors, discrepancies, and responses to CRMC‟s review 3.1 -Proofreading – done through page 100 (NG) - Inclusion of NWC Appendix K – completely done (NG) -Inclusion of CRMC comments at Appendix K- only “Boardwalks” not done (NG) 3.2 -Work in progress per CRMC‟s “Consistency . Determination Checklist” : From 10/03/05 meeting with K. Cute : From 12/13/05 meeting with K. Cute 3.3 -Updated Approx. J. – Hurricane Preparedness as recommend by K. Cute (HK Feb 06) 1/27/07 3.4 - Made changes from 3.3 : -Comments and suggestions from Kevin Cute -Corrects a few format errors -This version is eliminates correction notations -1 Dec 07 Hank Kniskern 3.5 -2 March 08 revisions made by Hank Kniskern and suggested Kevin Cute of CRMC. Full concurrence. -Only appendix charts and DEM water quality need update. Added Natural -

CHAPTER 4. Ecological Geography of the NBNERR

CHAPTER 4. Ecological Geography of the NBNERR CHAPTER 4. Ecological Geography of the NBNERR Kenneth B. Raposa 23 An Ecological Profile of the Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve Figure 4.1. Geographic setting of the NBNERR, including the extent of the 4,818 km2 (1,853-square-mile) Narragan- sett Bay watershed. GIS data sources courtesy of RIGIS (www.edc.uri.edu/rigis/) and Massachusetts GIS (www.mass. gov/mgis/massgis.htm). 24 CHAPTER 4. Ecological Geography of the NBNERR Ecological Geography of the NBNERR Geographic Setting Program in 2001. Annual weather patterns on Pru- dence Island are similar to those on the mainland, Prudence Island is located roughly in at least when considering air temperature, wind the center of Narragansett Bay, R.I., bounded by speed, and barometric pressure (Figure 4.3). 41o34.71’N and 41o40.02’N, and 71o18.16’W and Using recent data collected from the 71o21.24’W. Metropolitan Providence lies 14.4 NBNERR weather station, some annual patterns kilometers (km) (9 miles) to the north and the city are clear. For example, air temperature, relative of Newport lies 6.4 km (4 miles) to the south of humidity, and the amount of photosynthetically Prudence (Fig 4.1). Because of its central location, active radiation (PAR) all clearly peak during the Prudence Island is affected by numerous water summer months (Fig. 4.3). The total amount of masses in Narragansett Bay including nutrient-rich precipitation is generally highest during spring and freshwaters fl owing downstream from the Provi- fall, but this pattern is not as strong as the former dence and Taunton rivers and oceanic tidal water parameters based on these limited data. -

Ecological Profile Ch. 3 Land Use History

CHAPTER 3. Human and Land-Use History of the NBNERR CHAPTER 3. Human and Land-Use Joseph J. Bains and Robin L.J. Weber 15 An Ecological Profile of the Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve Figure 3.1. The Prudence Inn (built in 1894) contained more than 20 guestrooms. Postcard reproduction. 16 CHAPTER 3. Human and Land-Use History of the NBNERR Human and Land-Use History of the NBNERR Overview ary War. During the time that forests were being cleared, drainage of coastal and inland wetlands Prudence Island has had a long history of also occurred, which together with the deforesta- predominantly seasonal use, with a human popula- tion activities would have altered the hydrology of tion that has fl uctuated considerably due to changes the region (Niering, 1998). Changes in hydrology in the political climate. The location of Prudence would, in turn, infl uence future vegetation composi- Island near the center of Narragansett Bay, although tion. Although reforestation has occurred throughout considered isolated and relatively inaccessible by much of the region, the current forests are dissimilar today’s standards, made the island a highly desirable to the forests that existed prior to European settle- central location during periods when water travel ment, refl ected most notably in the reduction or loss was prevalent. of previously dominant or common species. In addi- The land-use practices on Prudence Island tion to forest compositional trends that can be linked are generally consistent with land-use practices to past land use, structurally the forests are most throughout New England from prehistoric periods often young and even aged (Foster, 1992). -

CHECKLIST of WISCONSIN MOTHS (Superfamilies Mimallonoidea, Drepanoidea, Lasiocampoidea, Bombycoidea, Geometroidea, and Noctuoidea)

WISCONSIN ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY SPECIAL PUBLICATION No. 6 JUNE 2018 CHECKLIST OF WISCONSIN MOTHS (Superfamilies Mimallonoidea, Drepanoidea, Lasiocampoidea, Bombycoidea, Geometroidea, and Noctuoidea) Leslie A. Ferge,1 George J. Balogh2 and Kyle E. Johnson3 ABSTRACT A total of 1284 species representing the thirteen families comprising the present checklist have been documented in Wisconsin, including 293 species of Geometridae, 252 species of Erebidae and 584 species of Noctuidae. Distributions are summarized using the six major natural divisions of Wisconsin; adult flight periods and statuses within the state are also reported. Examples of Wisconsin’s diverse native habitat types in each of the natural divisions have been systematically inventoried, and species associated with specialized habitats such as peatland, prairie, barrens and dunes are listed. INTRODUCTION This list is an updated version of the Wisconsin moth checklist by Ferge & Balogh (2000). A considerable amount of new information from has been accumulated in the 18 years since that initial publication. Over sixty species have been added, bringing the total to 1284 in the thirteen families comprising this checklist. These families are estimated to comprise approximately one-half of the state’s total moth fauna. Historical records of Wisconsin moths are relatively meager. Checklists including Wisconsin moths were compiled by Hoy (1883), Rauterberg (1900), Fernekes (1906) and Muttkowski (1907). Hoy's list was restricted to Racine County, the others to Milwaukee County. Records from these publications are of historical interest, but unfortunately few verifiable voucher specimens exist. Unverifiable identifications and minimal label data associated with older museum specimens limit the usefulness of this information. Covell (1970) compiled records of 222 Geometridae species, based on his examination of specimens representing at least 30 counties.