International Studies of the Modern Image, Vol.7 (2004), Pp.31-82

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optical Machines, Pr

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA UMI800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS Copyrighted materials in this document have not been filmed at the request of the author. They are available for consultation at the author’s university library. -

Elements of Screenology: Toward an Archaeology of the Screen 2006

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Erkki Huhtamo Elements of screenology: Toward an Archaeology of the Screen 2006 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1958 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Huhtamo, Erkki: Elements of screenology: Toward an Archaeology of the Screen. In: Navigationen - Zeitschrift für Medien- und Kulturwissenschaften, Jg. 6 (2006), Nr. 2, S. 31–64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1958. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

INSTRUCTION MANUAL Type C / N Design and Specifications Are Subject to Change Without Prior Notice

DIGITAL TTL MACRO FLASH Nissin Japan Ltd., Tokyo http://www.nissin-japan.com Nissin Marketing Ltd., Hong Kong INSTRUCTION MANUAL http://www.nissindigital.com Type C / N Design and Specifications are subject to change without prior notice. MF0611 REV. 1.1 Thank you for purchasing a Nissin product SIMPLE OPERATION When attaching MF18 to the camera, the basic flash exposure operation is fully Before using this flash unit, please read this instruction manual and refer controlled by the camera. It is the same idea as when you use the built-in your camera owner’s manual carefully to get a better understanding of camera flash, but it is placed on the hotshoe of the camera instead of using the proper operation to enjoy flash photography. built-in flash. Nissin Macro Flash MF18 is a flash system for taking close-up photos of small ADVANCED FUNCTIONS subjects using a flash to eliminate shadows, allowing you to enjoy photography. MF18 provides advanced flash functions including 1st curtain synchronization, This instruction manual is intended mainly for Canon or Nikon digital SLR, with Rear curtain synchronization and High speed shutter synchronization are the latest TTL flash control system, and features Nissin’s original rotating color supported. display, easily guiding its operations. It works automatically with Canon ETTL / ETTL II or Nikon i-TTL auto-flash systems. The provided adapter rings make it available for use with different lens. Please note that MF18 is not usable with other branded cameras for TTL Compatible cameras operation. Please refer Nissin’s compatibility chart shown in its home page for details. -

Advanced User Guide

Advanced User Guide E CT2-D068-A © CANON INC. 2020 Contents Introduction. 4 Instruction Manual. 5 About This Guide. 6 Safety Instructions. 8 Nomenclature. 10 Getting Started and Basic Operations. 26 Charging the Battery. 27 Insert the Battery. 31 Attaching and Detaching the Speedlite to and from the Camera. 33 Turning on the Power. 35 Fully Automatic Flash Photography. 40 E-TTL II / E-TTL Autoflash by Shooting Mode. 42 Checking the Battery Information. 47 Advanced Flash Photography. 49 Flash Exposure Compensation. 50 FEB. 52 FE Lock. 54 High-Speed Sync. 56 Second-Curtain Sync. 58 Bounce. 60 Set the Flash Coverage. 67 Manual Flash. 71 Stroboscopic Flash. 78 Flash External Metering. 82 Continuous Shooting Priority Mode. 87 About the Modeling Lamp. 88 Modeling Flash. 89 Color Filter. 90 Clearing Speedlite Settings. 92 Flash Function Settings with Camera Controls. 94 Flash Control from the Camera's Menu Screen. 95 Radio Transmission Wireless Flash Shooting. 102 Radio Transmission Wireless Flash Shooting. 103 Radio Transmission Wireless Settings. 110 Automatic Flash Photography with 1 Flash Receiver. 124 Automatic Flash Photography with Receivers divided into 2 Groups. 133 Automatic Flash Photography with Receivers divided into 3 Groups. 136 Wireless Multiple Flash Shooting with a set Flash Ratio. 141 Shooting in a Different Flash Mode for Each Group. 145 Test Flash / Modeling Flash from a Receiver Unit. 150 Remote Release from a Receiver Unit. 152 Linked Shooting with Radio Transmission. 154 Optical Transmission Wireless Flash Shooting. 159 Optical Transmission Wireless Flash Shooting. 160 Optical Transmission Wireless Settings. 164 Automatic Flash Photography with 1 Flash Receiver. -

Colour Relationships Using Traditional, Analogue and Digital Technology

Colour Relationships Using Traditional, Analogue and Digital Technology Peter Burke Skills Victoria (TAFE)/Italy (Veneto) ISS Institute Fellowship Fellowship funded by Skills Victoria, Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development, Victorian Government ISS Institute Inc MAY 2011 © ISS Institute T 03 9347 4583 Level 1 F 03 9348 1474 189 Faraday Street [email protected] Carlton Vic E AUSTRALIA 3053 W www.issinstitute.org.au Published by International Specialised Skills Institute, Melbourne Extract published on www.issinstitute.org.au © Copyright ISS Institute May 2011 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Whilst this report has been accepted by ISS Institute, ISS Institute cannot provide expert peer review of the report, and except as may be required by law no responsibility can be accepted by ISS Institute for the content of the report or any links therein, or omissions, typographical, print or photographic errors, or inaccuracies that may occur after publication or otherwise. ISS Institute do not accept responsibility for the consequences of any action taken or omitted to be taken by any person as a consequence of anything contained in, or omitted from, this report. Executive Summary This Fellowship study explored the use of analogue and digital technologies to create colour surfaces and sound experiences. The research focused on art and design activities that combine traditional analogue techniques (such as drawing or painting) with print and electronic media (from simple LED lighting to large-scale video projections on buildings). The Fellow’s rich and varied self-directed research was centred in Venice, Italy, with visits to France, Sweden, Scotland and the Netherlands to attend large public events such as the Biennale de Venezia and the Edinburgh Festival, and more intimate moments where one-on-one interviews were conducted with renown artists in their studios. -

Minolta Electronic Auto-Exposure 35Mm Single Lens Reflex Cameras and CLE

Minolta Electronic Auto-Exposure 35mm Single Lens Reflex Cameras and CLE Minolta's X-series 35mm single lens user the creative choice of aperture and circuitry requires a shutter speed faster reflex cameras combine state-of-the-art shutter-priority automation, plus metered than 1/1000 second. These cameras allow photographic technology with Minolta's tra manual operation at the turn of a lever. The full manual control for employing sophisti ditional fine handling and human engineer photographer can select shutter-priority cated photo techniques. The silent elec ing to achieve precision instruments that operation to freeze action or control the tronic self-timer features a large red LED are totally responsive to creative photogra amount of blur for creative effect. Aperture signal which pulsates with increasing fre phy. Through-the-Iens metering coupled priority operation is not only useful for quency during its ten-second operating with advanced, electronically governed depth-of-field control , auto~exposure with cycle to indicate the approaching exposure. focal-plane shutters provide highly accu bellows, extension tubes and mirror lenses, The Motor Drive 1, designed exclusively rate automatic exposure control. All X but for the control of shutter speed as well . for the XG-M, provides single-frame and series cameras are compatible with the Full metered-manual exposure control continuous-run film advance up to 3.5 vast array of lenses and accessories that allows for special techniques. frames per second. Plus, auto winders and comprise the Minolta single lens reflex A vibration-free electromagnetic shutter "dedicated" automatic electronic flash units system. release triggers the quiet electronic shutter. -

Nineteenth-Century Major Lives and Letters

Reading Popular Culture in Victorian Print 9780230615212ts01.indd i 9/2/2009 5:45:29 AM Nineteenth-Century Major Lives and Letters Series Editor: Marilyn Gaull The nineteenth century invented major figures: gifted, productive, and influential writers and artists in English, European, and American public life who captured and expressed what Hazlitt called “The Spirit of the Age.” Their achievements summarize, reflect, and shape the cultural traditions they inherited and influence the quality of life that followed. Before radio, film, and journalism deflected the energies of authors and audiences alike, literary forms such as popular verse, song lyrics, biographies, memoirs, letters, novels, reviews, essays, children’s books, and drama generated a golden age of letters incompara- ble in Western history. Nineteenth-Century Major Lives and Letters presents a series of original biographical, critical, and scholarly stud- ies of major figures evoking their energies, achievements, and their impact on the char- acter of this age. Projects to be included range from works on Blake to Hardy, Erasmus Darwin to Charles Darwin, Wordsworth to Yeats, Coleridge and J. S. Mill, Joanna Baillie, Jane Austen, Sir Walter Scott, Byron, Shelley, Keats to Dickens, Tennyson, George Eliot, Browning, Hopkins, Lewis Carroll, Rudyard Kipling, and their contemporaries. The series editor is Marilyn Gaull, PhD from Indiana University. She has served on the faculty at Temple University, New York University, and is now Research Professor at the Editorial Institute at Boston University. She brings to the series decades of experience as editor of books on nineteenth century literature and culture. She is the founder and editor of The Wordsworth Circle, author of English Romanticism: The Human Context, publishes edi- tions, essays, and reviews in numerous journals and lectures internationally on British Romanticism, folklore, and narrative theory. -

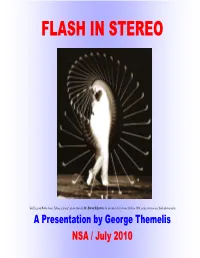

Flash in Stereo

FLASH IN STEREO “Golf Legend Bobby Jones Taking a Swing", photo taken by Dr. Harold Edgerton , the inventor of electronic flash in 1938, using stroboscopic flash photography. A Presentation by George Themelis NSA / July 2010 Outline • Why Flash? • Flash Advantages in Stereo • Short History of Flash Photography • Flash Bulbs vs. Electronic Flash • Flash Synchronization • Flash Exposure • Issues when using flash • Special Flash Techniques • Flash in Slide Bar (Single camera) Stereo • Flash with Vintage Stereo Cameras • Flash with compact digital stereo cameras • Flash with twin cameras Why Flash? When the existing light is dim, there is a need for artificial light in order to get good expo- sures . Example: In a well-lit interior space a typical exposure using 100 ISO is f8 at 1 second. Compare this to a “sunny day” f16 1/100, 2+7 = 9 f-stops less light. Hand hold- ing the camera or taking pictures of people at these long exposures is impossible. Hence flash is a necessity for taking pictures indoors. Without extra light, the photographer has three options: 1) Open up the aperture (f-stop), 2) Increase the time of the exposure . 3) Increase sensitivity (ISO) . These methods have disadvantages & limitations: • Opening up the lens aperture reduces the depth of field (can be a problem in stereo) in- creases lens aberrations, plus there is a limit (lens maximum aperture) • Theoretically, there is no limit in increasing exposure time, but in practice 1) film recip- rocity, 2) digital noise, 3) blurry pictures without solid support, 4) subject movement. • Increased sensitivity leads to film grain or digital noise. -

Le Théâtre Lambe-Lambe Son Histoire Et Sa Poésie Du Petit

Université Charles de Gaulle – Lille 3 UFR Humanités – Département Arts Année universitaire 2016-2017 Le Théâtre Lambe-Lambe Son histoire et sa poésie du petit Master 1 Arts Parcours théories et pratiques du théâtre contemporain Sous la direction de Mme. Véronique PERRUCHON Soutenu par Pedro Luiz COBRA SILVA Juin 2017 REMERCIEMENTS Je tiens à remercier ici celles et ceux qui ont contribué à la réalisation de ce mémoire : Tout d'abord Madame Véronique Perruchon, directrice de ce mémoire, pour le suivi et les conseils apportés. Des remerciements spéciaux à Ismine Lima et Denise Di Santos, créatrices du Théâtre Lambe- Lambe, qui ont partagé leurs histoires et leurs connaissances avec toute humilité et amour. Un grand merci à l’équipe de production du 4º FESTILAMBE – Festival de Teatro Lambe-Lambe de Valparaíso et aux lambe-lambeiros et lambe-lambeiras qui ont participé à cet événement au Chili avec moi. Votre passion, vos remarques et vos développements apportés à l’art du Théâtre Lambe-Lambe m’ont beaucoup aidé à écrire ce mémoire. Merci à mes nouveaux amis et amies de Lille pour leur aide et leur sourire lors de mon adaptation en France. Merci à ma famille qui me manque beaucoup pour leurs conseils et leur soutien tout au long de mon année universitaire à l’étranger. Enfin, merci à ma compagne Larissa qui prend ma main dans les voyages de la vie. Merci pour son amour, sa joie et patience. TABLE DE MATIÈRES INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................................................1 -

Pro-B3 1200 Airs User´S Guide

Pro-B3 1200 AirS User´s Guide Pro-B3 1200 AirS 2 www.profoto.com Pro-B3 1200 AirS Thank you for choosing Profoto Thanks for showing us your confidence by investing in a Pro- B3 generator. For more than four decades we have sought the perfect light. What pushes us is our conviction that we can offer even yet better tools for the most demanding photographers. 3 Before our products are shipped we have them pass an extensive and strict testing program. We check that each individual product comply with specified performance, quality and safety. For this reason our flash equipment is widely used in rental studios and rental houses worldwide, from Paris, London, Milan, New York, Tokyo to Cape Town. Some photographers can tell just from seeing a picture, if Profoto equipment has been used. Professional photographers around the world have come to value Profoto’s expertise in lighting and light-shaping. Our extensive range of Light Shaping Tools offers photographers unlimited possibilities for creating and adjusting their own light. Every single reflector and accessory creates its special light and the unique Profoto focusing system offers you the possibility to create your own light with only a few different reflectors. Enjoy your Profoto product! www.profoto.com Safety instructions SAfeTy PrecAUTionS! Do not operate the equipment before studying the instruction manual and the accompanying safety. Make Pro-B3 1200 AirS sure that Profoto Safety Instructions is always accompanied the equipment! Profoto products are intended for professional use! Generator, lamp heads and accessories are only intended for indoor photographic use. -

Graphic Materials: Rules for Describing Original Items and Historical Collections

GRAPHIC MATERIALS Rules for Describing Original Items and Historical Collections compiled by Elisabeth W. Betz Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 1982 WordPerfect version 6/7/8 (July 2000; with MARC21 tagging added March 2002) With cumulated updates: 1982-1996 and List of areas to update for second edition: 1997-2000 Cover illustration: "Sculptor. Der Formschneider." Woodcut by Jost Amman in Hartmann Schopper's Panoplia, omnium illiberalium mechanicarum aut sedentariarum artium genera continens, printed at Frankfurt am Main by S. Feyerabent, 1568. Rosenwald Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division. (Neg. no. LC-USZ62-44613) TABLE OF CONTENTS Graphic Materials (1996-1997 Updates)...................p. i Issues to consider for second edition (1997-2000).......p. iii Preface.................................................p. 1 Introduction............................................p. 3 0. General Rules........................................p. 8 0A. Scope.............................................p. 8 0B. Sources of information............................p. 9 0C. Punctuation.......................................p. 10 0D. Levels of description.............................p. 12 0E. Language and script of the description............p. 13 0F. Inaccuracies......................................p. 14 0G. Accents and other diacritical marks (including capitalization)..................................p. 14 0H. Abbreviations, initials, etc......................p. 14 0J. Interpolations....................................p. 15 1. -

TESSERACT -- Antique Scientific Instruments

TESSERACT Early Scientific Instruments Special Issue: OPTICAL PLEASURES Catalogue One Hundred Seven Summer, 2018 $10 CATALOGUE ONE HUNDRED SEVEN Copyright 2018 David Coffeen CONDITIONS OF SALE All items in this catalogue are available at the time of printing. We do not charge for shipping and insurance to anywhere in the contiguous 48 states. New York residents must pay applicable sales taxes. For buyers outside the 48 states, we will provide packing and delivery to the post office or shipper but you must pay the actual shipping charges. Items may be reserved by telephone, and will be held for a reasonable time pending receipt of payment. All items are offered with a 10-day money-back guarantee for any reason, but you pay return postage and insurance. We will do everything possible to expedite your shipment, and can work within the framework of institutional requirements. The prices in this catalogue are net and are in effect through December, 2018. Payments by check, bank transfer, or credit card (Visa, Mastercard, American Express) are all welcome. — David Coffeen, Ph.D. — Yola Coffeen, Ph.D. Members: Scientific Instrument Society American Association for the History of Medicine Historical Medical Equipment Society Antiquarian Horological Society International Society of Antique Scale Collectors Surveyors Historical Society Early American Industries Association The Oughtred Society American Astronomical Society International Coronelli Society American Association of Museums Co-Published : RITTENHOUSE: The Journal of the American Scientific Instrument Enterprise (http://www.etesseract.com/RHjournal/) We are always interested in buying single items or collections. In addition to buying and selling early instruments, we can perform formal appraisals of your single instruments or whole collections, whether to determine fair market value for donation, for insurance, for loss, etc.