Spiritual Practice in a Social Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kriya Yoga of Mahavatar Babaji

Kriya Yoga of Mahavatar Babaji Kriya Yoga Kriya Yoga, the highest form of pranayam (life force control), is a set of techniques by which complete realization may be achieved. In order to prepare for the practice of Kriya Yoga, the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are to be studied, the Eight Fold Path learned and adheared to; the Bhagavad Gita is to be read, studied and meditated upon; and a Disciple-Guru relationship entered into freely with the Guru who will initiate the disciple into the actual Kriya Yoga techniques. These techniques themselves, given by the Guru, are to be done as per the Mahavatar Babaji gurus instructions for the individual. There re-introduced this ancient technique in are also sources for Kriya that are guru-less. 1861 and gave permission for it's See the Other Resources/Non Lineage at the dissemination to his disciple Lahiri bottom of organizations Mahasay For more information on Kriya Yoga please use these links and the ones among the list of Kriya Yoga Masters. Online Books A Personal Experience More Lineage Organizations Non Lineage Resources Message Boards/Groups India The information shown below is a list of "Kriya Yoga Gurus". Simply stated, those that have been given permission by their Guru to initiate others into Kriya Yoga. Kriya Yoga instruction is to be given directly from the Guru to the Disciple. When the disciple attains realization the Guru may give that disciple permission to initiate and instruct others in Kriya Yoga thus continuing the line of Kriya Yoga Gurus. Kriya Yoga Gurus generally provide interpretations of the Yoga Sutras and Gitas as part of the instructions for their students. -

Sri Ramakrishna Math

Sri Ramakrishna Math 31, Ramakrishna Math Road, Mylapore, Chennai - 600 004, India & : 91-44-2462 1110 / 9498304690 email: [email protected] / website: www.chennaimath.org Catalogue of some of our publications… Buy books online at istore.chennaimath.org & ebooks at www.vedantaebooks.org Some of Our Publications... Sri Ramakrishna the Great Master Swami Saradananda / Tr. Jagadananda This book is the most comprehensive, authentic and critical estimate of the life, sadhana, and teachings of Sri Ramakrishna. It is an English translation of Sri Sri Ramakrishna Lila-prasanga written in Bengali by Swami Saradananda, a direct disciple of Sri Ramakrishna and who is deemed an authority both as a philosopher and as a biographer. His biographical narrative of Sri Ramakrishna Volume 1 is based on his firsthand observations, assiduous collection of material from Pages 788 | Price ` 200 different authentic sources, and patient sifting of evidence. Known for his vast Volume 2 erudition, spirit of rational enquiry and far-reaching spiritual achievements, Pages 688 | Price ` 225 he has interspersed the narrative with lucid interpretations of various religious cults, mysticism, philosophy, and intricate problems connected with the theory and practice of religion. Translated faithfully into English by Swami Jagadananda, who was a disciple of the Holy Mother, this book may be ranked as one of the best specimens in hagiographic literature. The book also contains a chronology of important events in the life of Sri Ramakrishna, his horoscope, and a short but beautiful article by Swami Nirvedananda on the book and its author. This firsthand, authentic book is a must- read for everyone who wishes to know about and contemplate on the life of Sri Ramakrishna. -

Annual Report 2003-2004

ANNUAL REPORT 2003-2004 ■inaiiiNUEPA DC D12685 UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi-110 002 (India) UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION LIST OF THE COMMISSION MEMBERS DURING 2003-2004 Chairman Dr. Arun Nigavekar ■;ir -Chariman Prof. V.N. Rajasekharan Pillai /».. bers 1. Shri S.K. Tripathi 2. Shri Dinesh Chander Gupta 3. Dr. S.K. Joshi 4. Prof. Sureshwar Sharma ++ 5. Prof. B.H. Briz Kishore ++ 6. Prof. Vasant Gadre 7. Prof. Ashok Kumar Gupta 8. Dr. G. Mohan Gopai * 9. Dr. G. Karunakaran Pillai 10. Prof. Arana Goel 11. Dr. P.N. Tandon$ Secretary Prof. Ved Prakash # w.e.f. 30.04.2003 ++ Second Term w.e.f. 16.06.2003 * upto 11.06.2003 $ w.e.f. 12.06.2003 CONTENTS Highlights of the University Grants Commission 1 1. Introduction 1.1 Role and Organization of UGC 13 1.2 About Tenth Plan 14 1.3 Special Cells Functioning in the UGC 15 a) Malpractices Cell 15 b) Legal Cell 16 c) Vigilance Cell 17 d) Pay Scale Cell 17 e) Sexual Harassment Complaint Committee of UGC 17 f) Internal Audit Cell 17 g) Desk: Parliament Matters 18 1.4 Publications 19 1.5 The Budget and Finances of UGC 19 1.6 Computerisation of UGC 20 1.7 Highlights of the Year 21 2. Higher Education System: Statistical Growth of Institutions, Enrolment, Faculty and Research 2.1 Institutions 36 2.2 Students Enrolment 38 2.3 Faculty Strength 38 2.4 Research Degrees 39 2.5 Growth in Enrolment of Women in Higher Education 39 2.6 Distribution of Women Enrolment by State, Stage and Faculty 39 2.7 Women Colleges 41 3. -

Sri Ramakrishna & His Disciples in Orissa

Preface Pilgrimage places like Varanasi, Prayag, Haridwar and Vrindavan have always got prominent place in any pilgrimage of the devotees and its importance is well known. Many mythological stories are associated to these places. Though Orissa had many temples, historical places and natural scenic beauty spot, but it did not get so much prominence. This may be due to the lack of connectivity. Buddhism and Jainism flourished there followed by Shaivaism and Vainavism. After reading the lives of Sri Chaitanya, Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother and direct disciples we come to know the importance and spiritual significance of these places. Holy Mother and many disciples of Sri Ramakrishna had great time in Orissa. Many are blessed here by the vision of Lord Jagannath or the Master. The lives of these great souls had shown us a way to visit these places with spiritual consciousness and devotion. Unless we read the life of Sri Chaitanya we will not understand the life of Sri Ramakrishna properly. Similarly unless we study the chapter in the lives of these great souls in Orissa we will not be able to understand and appreciate the significance of these places. If we go on pilgrimage to Orissa with same spirit and devotion as shown by these great souls, we are sure to be benefited spiritually. This collection will put the light on the Orissa chapter in the lives of these great souls and will inspire the devotees to read more about their lives in details. This will also help the devotees to go to pilgrimage in Orissa and strengthen their devotion. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

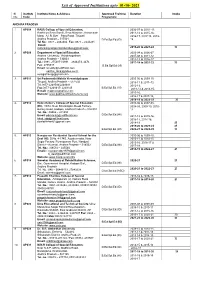

List of Approved Institutions Upto 11-08

List of Approved Institutions upto 01-10- 2021 Sl. Institute Institute Name & Address Approved Training Duration Intake No. Code Programme ANDHRA PRADESH 1. AP004 RASS College of Special Education, 2006-07 to 2010 -11, Rashtriya Seva Samiti, Seva Nilayram, Annamaiah 2011-12 to 2015-16, Marg, A.I.R. Bye – Pass Road, Tirupati, 2016-17, 2017-18, 2018- Andhra Pradesh – 517501 D.Ed.Spl.Ed.(ID) 19, Tel No.: 0877 – 2242404 Fax: 0877 – 2244281 Email: [email protected]; 2019-20 to 2023-24 30 2. AP008 Department of Special Education, 2003-04 to 2006-07 Andhra University, Vishakhapatnam 2007-08 to 2011-12 Andhra Pradesh – 530003 2012-13 to 2016-17 Tel.: 0891- 2754871 0891 – 2844473, 4474 2017-18 to 2021-22 30 Fax: 2755547 B.Ed.Spl.Ed.(VI) Email: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] 3. AP011 Sri Padmavathi Mahila Visvavidyalayam , 2005-06 to 2009-10 Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh – 517 502 2010-11 & 2011–12 Tel:0877-2249594/2248481 2012-13, Fax:0877-2248417/ 2249145 B.Ed.Spl.Ed.(HI) 2013-14 & 2014-15, E-mail: [email protected] 2015-16, Website: www.padmavathiwomenuniv.org 2016-17 & 2017-18, 2018-19 to 2022-23 30 4. AP012 Helen Keller’s College of Special Education 2005-06 to 2007-08, (HI), 10/72, Near Shivalingam Beedi Factory, 2008-09, 2009-10, 2010- Bellary Road, Kadapa, Andhra Pradesh – 516 001 11 Tel. No.: 08562 – 241593 D.Ed.Spl.Ed.(HI) Email: [email protected] 2011-12 to 2015-16, [email protected]; 2016-17, 2017-18, [email protected] 2018-19 25 2019-20 to 2023-24 25 B.Ed.Spl.Ed.(HI) 2020-21 to 2024-25 30 5. -

Karmic Philosophy and the Model of Disability in Ancient India OPEN ACCESS Neha Kumari Research Scholar, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India

S International Journal of Arts, Science and Humanities Karmic Philosophy and the Model of Disability in Ancient India OPEN ACCESS Neha Kumari Research Scholar, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India Volume: 7 Abstract Disability has been the inescapable part of human society from ancient times. With the thrust of Issue: 1 disability right movements and development in eld of disability studies, the mythical past of dis- ability is worthy to study. Classic Indian Scriptures mention differently able character in prominent positions. There is a faulty opinion about Indian mythology is that they associate disability chie y Month: July with evil characters. Hunch backed Manthara from Ramayana and limping legged Shakuni from Mahabharata are negatively stereotyped characters. This paper tries to analyze that these charac- ters were guided by their motives of revenge, loyalty and acted more as dramatic devices to bring Year: 2019 crucial changes in plot. The deities of lord Jagannath in Puri is worshipped , without limbs, neck and eye lids which ISSN: 2321-788X strengthens the notion that disability is an occasional but all binding phenomena in human civiliza- tion. The social model of disability brings forward the idea that the only disability is a bad attitude for the disabled as well as the society. In spite of his abilities Dhritrashtra did face discrimination Received: 31.05.2019 because of his blindness. The presence of characters like sage Ashtavakra and Vamanavtar of Lord Vishnu indicate that by efforts, bodily limitations can be transcended. Accepted: 25.06.2019 Keywords: Karma, Medical model, Social model, Ability, Gender, Charity, Rights. -

Why Should I Take Admission in NIOS Vocational Education Courses?

PROSPECTUS 2013 With Application Form for Admission Vocational Education Courses National Institute of Open Schooling (An autonomous organisation under MHRD, Govt. of India) A-24-25, Institutional Area, Sector-62, NOIDA (U.P.) - 201309 Website: www.nios.ac.in “The Largest Open Schooling System in the World” i Why should I take admission in Facts and Figures NIOS Vocational Education Courses? about NIOS l The largest Open Schooling system in the world: more than 1. Freedom to Learn 2.45 million learners have taken admission since 1990. With the motto to ‘reach out and reach all’, the NIOS follows the principle of freedom to learn. What to learn, when to learn, l More than 25,000 learners take how to learn and when to appear for the examination is decided admission every year in Vocational Education Courses by you. There is no restriction of time, place and pace of and more than 3,50,000 are learning. enrolled in all the courses and programmes. 2. Flexibility l 1,44,799 learners have been The NIOS provides flexibilities such as: certified in different Vocational Education Courses since May l Round the year Admission: You can take admission online or through Accredited 1993. Vocational Institute round the year. Admission in Vocational Courses can also be done through On-line mode. l NIOS reaches out to its clients through a network of more l Choice of courses: Choose courses of your choice from the given list keeping than 1725 Vocational Education the eligibility criteria in mind. centres spread all over the l Examination when you want: Public Examinations are held twice in a year. -

PROGRAMS 2019 Sivanandayogaranch.Org | 845.436.6492

2019 PROGRAMS 2019 sivanandayogaranch.org | 845.436.6492 sivanandayogaranch.org | 845.436.6492 WELCOME TO THE YOGA RANCH Om Namo Narayanaya, Blessed Self, Whether you are considering your first Yoga Vacation, or a residential Yoga Teacher Training Course, or you are a Yoga teacher preparing for a more advanced training, or an old friend of the Ashram returning to nourish your personal practice with a seasonal Yoga Retreat, we welcome you. And we especially welcome you who are relatively new to Yoga and Ashram life. We would like to prepare you for a new kind of unforgettable vacation. What is your “bottom line” for a vacation? A vacation is both a renewal and a reward for many hours of hard work that have opened the space in life where you can get away, rest and renew, and reconnect to what is really meaningful. Yoga, by definition, is that reconnection and renewal. Yoga— physically, emotionally, philosophically, integrally, mystically, and spiritually— offers pathways to that reconnection. It can be hard work, but it is work that strengthens, invigorates, and nourishes the body, mind, and soul. Come join us to rediscover your inner sacred space with twice daily Yoga asana classes and meditation satsangs. Explore the sacred nature that feeds our bodies, minds, and souls with quiet forest walks, or dig into the Ashram gardens that provide us with fruits, vegetables, and flowers. The bottom line of Yoga living is delving into the sacred. This is the goal of an Ashram vacation. Dive deep within and reconnect to the sacred. Find sacred silence. -

List of Marathi Books S.N

LIST OF MARATHI BOOKS S.N. ITEM CODE ITEM NAME ITEM PRICE AUTHOR 1) M05210 AADHUNIK BHARAT Y9 M:10 ₹ 10.00 SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AADHUNIK MANAVALA UPANISHADANCHA SANDESH 2) M9512 ₹ 12.00 SWAMI SHIVATATTWANANDA Y4 M:12 3) M11150 ACHARYA SHANKARA Y15 M:50 ₹ 50.00 SWAMI APURVANANDA 4) M20635 ADARSH SHIKSHAN M:35 ₹ 35.00 SWAMI VIVEKANANDA 5) M13520 ADBHUTANANDANCHI ADBHUT KAHANI Y7 M:20 ₹ 20.00 NAGPUR 6) M09225 ADHUNIK BHARAT ANI R.K.-S.V. Y19 M:25 ₹ 25.00 SWAMI SHIVTATTWANANDA 7) M14130 ADHYATMA-MARGA-DIPIKA Y9 M:30 ₹ 30.00 SWAMI TURIYANANDA 8) M17425 ADHYATMIK SADHANA Y12 M:25 ₹ 25.00 SWAMI ASHOKANANDA 9) M18030 ADHYATMIK SAMVAD: SW. VIDNYNANANDA Y3 M:30 ₹ 30.00 SWAMI APURVANANDA 10) M7115 AGHORMANI VA GAURI MA Y4 M:15 ₹ 15.00 SWAMI SHIVTTWANANDA 11) M16840 AGNIMANTRA (MARATHI) Y35 M:40 ₹ 40.00 SWAMI VIVEKANANDA 12) M12625 AKHANDANANDACHNYA SAHAVASAT Y13 M:25 ₹ 25.00 SWAMI NIRAMAYANANDA 13) M09320 AMCHI MUKHYA SAMASYA ANI SRK AND SV M:20 ₹ 20.00 SWAMI SHIVATATWANANDA 14) M159150 AMHI PAHILELE S.V. M:150 ₹ 150.00 K V S BENODEKAR 15) M2085 AMRIT SANDESH M:5 ₹ 5.00 NGP 16) M246250 AMRITASYA PUTRA M:250 ₹ 250.00 SWAMI VIVEKANANDA 17) M13060 AMRUTAVANI (MARATHI) Y26 M:60 ₹ 60.00 NAGPUR 18) M10780 ANANDADHAMA KADE Y4 M:80 ₹ 80.00 SW APURVANANDA 19) M25215 APALA BHARAT APALI SANSKRUTI M:15 ₹ 15.00 SWAMI VIVEKANANDA 20) M22410 ATMABODH Y20 M:10 ₹ 10.00 SWAMI VIPAPPANANANDA 21) M04725 ATMASAKSHATKAR:SADHANA VA SIDDHI Y38 M:25 ₹ 25.00 SWAMI VIVEKANANDA 22) M16615 ATMA-TATTWA Y11 M:15 ₹ 15.00 SW VIVEKANANDA 23) M24960 ATMONNATICHE SOPAN M:60 ₹ 60.00 SWAMI -

Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: from Swami Vivekananda to the Present

Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: From Swami Vivekananda to the Present Appendix I: Ramakrishna-Vedanta Swamis in Southern California and Affiliated Centers (1899-2017) Appendix II: Ramakrishna-Vedanta Swamis (1893-2017) Appendix III: Presently Existing Ramakrishna-Vedanta Centers in North America (2017) Appendix IV: Ramakrishna-Vedanta Swamis from India in North America (1893-2017) Bibliography Alphabetized by Abbreviation Endnotes Appendix 12/13/2020 Page 1 Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: From Swami Vivekananda to the Present Appendix I: Ramakrishna Vedanta Swamis Southern California and Affiliated Centers (1899-2017)1 Southern California Vivekananda (1899-1900) to India Turiyananda (1900-02) to India Abhedananda (1901, 1905, 1913?, 1914-18, 1920-21) to India—possibly more years Trigunatitananda (1903-04, 1911) Sachchidananda II (1905-12) to India Prakashananda (1906, 1924)—possibly more years Bodhananda (1912, 1925-27) Paramananda (1915-23) Prabhavananda (1924, 1928) _______________ La Crescenta Paramananda (1923-40) Akhilananda (1926) to Boston _______________ Prabhavananda (Dec. 1929-July 1976) Ghanananda (Jan-Sept. 1948, Temporary) to London, England (Names of Assistant Swamis are indented) Aseshananda (Oct. 1949-Feb. 1955) to Portland, OR Vandanananda (July 1955-Sept. 1969) to India Ritajananda (Aug. 1959-Nov. 1961) to Gretz, France Sastrananda (Summer 1964-May 1967) to India Budhananda (Fall 1965-Summer 1966, Temporary) to India Asaktananda (Feb. 1967-July 1975) to India Chetanananda (June 1971-Feb. 1978) to St. Louis, MO Swahananda (Dec. 1976-2012) Aparananda (Dec. 1978-85) to Berkeley, CA Sarvadevananda (May 1993-2012) Sarvadevananda (Oct. 2012-) Sarvapriyananda (Dec. 2015-Dec. 2016) to New York (Westside) Resident Ministers of Affiliated Centers: Ridgely, NY Vivekananda (1895-96, 1899) Abhedananda (1899) Turiyananda (1899) _______________ (Horizontal line means a new organization) Atmarupananda (1997-2004) Pr. -

Gauri Maa.Indd 61 10/19/2011 4:55:42 PM Modern Prototype Her

Spirit profi le With her fiery, independent spirit, bottomless courage and managerial prowess, Gauri Ma, who founded India’s first ashram for women, the Sri Saradeshwari Ashram, is a role model for the modern woman seeker, rhapsodises Nandini Sarkar Gauri Ma The mystic manager woman was drowning in the Mother Kali,” and threw herself into the river – this Ganga and a crowd of men was despite the fact that she did not know how to swim! watching from the banks, rais- Realising that Gauri Ma could not swim out far ing a commotion but not going enough to save the drowning woman, a few people forward to help her. A sanyasi- from the crowd finally jumped in and saved her. Ani who had come to the spot scornfully Gauri Ma has long been a hero for me, ever since I addressed the men, “There is a person read about her in Swami Nikhilananda’s, They Lived drowning, yet all of you men are standing With God. Sri Ramakrishna said of her, “Gauri is that here and watching the show.” Without a gopi who has received the grace of the Lord through moment's hesitation, she shouted, “Jai many births. She is a gopi from Brindavan.” LIFE POSITIVE NOVEMBER 2011 61 gauri maa.indd 61 10/19/2011 4:55:42 PM Modern prototype her. Balaram came up to her and asked if Though born in backward nineteenth century India, she would like to visit Dakshineshwar. As she epitomised the modern empowered woman, they entered Sri Ramakrishna's room, he seeking to balance the spiritual with the temporal.