Photoluminescence by Interstellar Dust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Constellations

Winter Constellations *Orion *Canis Major *Monoceros *Canis Minor *Gemini *Auriga *Taurus *Eradinus *Lepus *Monoceros *Cancer *Lynx *Ursa Major *Ursa Minor *Draco *Camelopardalis *Cassiopeia *Cepheus *Andromeda *Perseus *Lacerta *Pegasus *Triangulum *Aries *Pisces *Cetus *Leo (rising) *Hydra (rising) *Canes Venatici (rising) Orion--Myth: Orion, the great hunter. In one myth, Orion boasted he would kill all the wild animals on the earth. But, the earth goddess Gaia, who was the protector of all animals, produced a gigantic scorpion, whose body was so heavily encased that Orion was unable to pierce through the armour, and was himself stung to death. His companion Artemis was greatly saddened and arranged for Orion to be immortalised among the stars. Scorpius, the scorpion, was placed on the opposite side of the sky so that Orion would never be hurt by it again. To this day, Orion is never seen in the sky at the same time as Scorpius. DSO’s ● ***M42 “Orion Nebula” (Neb) with Trapezium A stellar nursery where new stars are being born, perhaps a thousand stars. These are immense clouds of interstellar gas and dust collapse inward to form stars, mainly of ionized hydrogen which gives off the red glow so dominant, and also ionized greenish oxygen gas. The youngest stars may be less than 300,000 years old, even as young as 10,000 years old (compared to the Sun, 4.6 billion years old). 1300 ly. 1 ● *M43--(Neb) “De Marin’s Nebula” The star-forming “comma-shaped” region connected to the Orion Nebula. ● *M78--(Neb) Hard to see. A star-forming region connected to the Orion Nebula. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Kuchner, M. & Seager, S., Extrasolar Carbon Planets, Arxiv:Astro-Ph

Extrasolar Carbon Planets Marc J. Kuchner1 Princeton University Department of Astrophysical Sciences Peyton Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544 S. Seager Carnegie Institution of Washington, 5241 Broad Branch Rd. NW, Washington DC 20015 [email protected] ABSTRACT We suggest that some extrasolar planets . 60 ML will form substantially from silicon carbide and other carbon compounds. Pulsar planets and low-mass white dwarf planets are especially good candidate members of this new class of planets, but these objects could also conceivably form around stars like the Sun. This planet-formation pathway requires only a factor of two local enhancement of the protoplanetary disk’s C/O ratio above solar, a condition that pileups of carbonaceous grains may create in ordinary protoplanetary disks. Hot, Neptune- mass carbon planets should show a significant paucity of water vapor in their spectra compared to hot planets with solar abundances. Cooler, less massive carbon planets may show hydrocarbon-rich spectra and tar-covered surfaces. The high sublimation temperatures of diamond, SiC, and other carbon compounds could protect these planets from carbon depletion at high temperatures. arXiv:astro-ph/0504214v2 2 May 2005 Subject headings: astrobiology — planets and satellites, individual (Mercury, Jupiter) — planetary systems: formation — pulsars, individual (PSR 1257+12) — white dwarfs 1. INTRODUCTION The recent discoveries of Neptune-mass extrasolar planets by the radial velocity method (Santos et al. 2004; McArthur et al. 2004; Butler et al. 2004) and the rapid development 1Hubble Fellow –2– of new technologies to study the compositions of low-mass extrasolar planets (see, e.g., the review by Kuchner & Spergel 2003) have compelled several authors to consider planets with chemistries unlike those found in the solar system (Stevenson 2004) such as water planets (Kuchner 2003; Leger et al. -

1 Towards a Molecular Inventory of Protostellar

TOWARDS A MOLECULAR INVENTORY OF PROTOSTELLAR DISCS Glenn J White (1), Mark A. Thompson (1), C.V. Malcolm Fridlund (2), Monica Huldtgren White (3) (1) University of Kent, UK, [email protected] (2) ESTEC, NL, (3) Stockholm Observatory, Sweden Abstract solid, atomic and ionised material in the pre- planetary environment. The chemical environment in circumstellar discs is a unique diagnostic of the thermal, physical and Details of the survey chemical environment. In this paper we examine the structure of star formation regions giving rise to low We are carrying out a survey of nearby star mass stars, and the chemical environment inside formation regions to them, and the circumstellar discs around the developing stars. • Search in the optical/IR region for triggered/induced solar-type star formation. Introduction We measure the boundary conditions, such as external pressure of ionised gas that Life develops from a sequence of organic chemical triggering the star formation using radio processes that develop sufficient complexity to lead observations, and from molecular line to mutating and self-replicating sentient organisms. tracers, estimate the internal pressure in the Cellular structures, formed following selective molecular gas. evolution along the Tree of Life, emerged from the • Characterise the properties of the central reactions amongst these simple organic compounds, protostellar core and protostellar discs at which were derived from cosmically abundant submm, mid and near-IR wavelengths, by elements and molecules that are abundant in space. measuring the spectral energy distributions Much of this early chemical inventory was delivered and the atomic and molecular inventory of a to the surfaces of planets, including the Earth, during sample of circumstellar discs the early phase of massive cometary bombardment of • Measure the chemical inventory of gas- the earth - e.g. -

Observing Dust Grain Growth and Sedimentation in Circumstellar Discs Interpretations and Predictions of Their Observable Quantities in a Multi-Wavelength Approach

Observing dust grain growth and sedimentation in circumstellar discs Interpretations and predictions of their observable quantities in a multi-wavelength approach Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Fakult¨at der Christian-Albrechts Universit¨atzu Kiel vorgelegt von J¨urgenSauter Kiel, 2011 Referent : Prof. Dr. S. Wolf Koreferent: Prof. Dr. C. Dullemond Tag der m¨undlichen Pr¨ufung: 7. Juli 2011 Zum Druck genehmigt: 7. Juli 2011 gez. Prof. Dr. L. Kipp, Dekan To my growing family Abstract In the present thesis, the observational effects of dust grain growth and sedimentation in circumstellar discs are investigated. The growth of dust grains from some nanometres in diameter as found in the inter- stellar medium towards planetesimal bodies some meters in diameter is an important step in the formation of planets. However, this process is currently not entirely un- derstood. Especially, in the literature several `barriers' are discussed that apparently prohibit an effective growth of dust grains. Hence, it is of particular interest to compare theories and observational data in this respect. State-of-the-art radiative transfer techniques allow one to derive observable quantities from theoretical models that allow this comparison. In this thesis, generic tracers of dust grain growth in spatially high resolution multi-wavelength images are identified for the first time. Further, a possibility to detect a dust trapping mechanism for dust grains by local pressure maxima using the new interferometer, ALMA, is established. By fitting parametric models to new observations of the disc in the Bok globule CB 26, unexpected features of the system are revealed, such as a large inner void and the possibility to interpret the data without the need for grain growth. -

Nova Report 2006-2007

NOVA REPORTNOVA 2006 - 2007 NOVA REPORT 2006-2007 Illustration on the front cover The cover image shows a composite image of the supernova remnant Cassiopeia A (Cas A). This object is the brightest radio source in the sky, and has been created by a supernova explosion about 330 year ago. The star itself had a mass of around 20 times the mass of the sun, but by the time it exploded it must have lost most of the outer layers. The red and green colors in the image are obtained from a million second observation of Cas A with the Chandra X-ray Observatory. The blue image is obtained with the Very Large Array at a wavelength of 21.7 cm. The emission is caused by very high energy electrons swirling around in a magnetic field. The red image is based on the ratio of line emission of Si XIII over Mg XI, which brings out the bi-polar, jet-like, structure. The green image is the Si XIII line emission itself, showing that most X-ray emission comes from a shell of stellar debris. Faintly visible in green in the center is a point-like source, which is presumably the neutron star, created just prior to the supernova explosion. Image credits: Creation/compilation: Jacco Vink. The data were obtained from: NASA Chandra X-ray observatory and Very Large Array (downloaded from Astronomy Digital Image Library http://adil.ncsa.uiuc. edu). Related scientific publications: Hwang, Vink, et al., 2004, Astrophys. J. 615, L117; Helder and Vink, 2008, Astrophys. J. in press. -

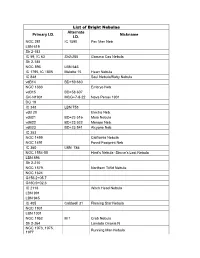

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

Meeting Program

A A S MEETING PROGRAM 211TH MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY WITH THE HIGH ENERGY ASTROPHYSICS DIVISION (HEAD) AND THE HISTORICAL ASTRONOMY DIVISION (HAD) 7-11 JANUARY 2008 AUSTIN, TX All scientific session will be held at the: Austin Convention Center COUNCIL .......................... 2 500 East Cesar Chavez St. Austin, TX 78701 EXHIBITS ........................... 4 FURTHER IN GRATITUDE INFORMATION ............... 6 AAS Paper Sorters SCHEDULE ....................... 7 Rachel Akeson, David Bartlett, Elizabeth Barton, SUNDAY ........................17 Joan Centrella, Jun Cui, Susana Deustua, Tapasi Ghosh, Jennifer Grier, Joe Hahn, Hugh Harris, MONDAY .......................21 Chryssa Kouveliotou, John Martin, Kevin Marvel, Kristen Menou, Brian Patten, Robert Quimby, Chris Springob, Joe Tenn, Dirk Terrell, Dave TUESDAY .......................25 Thompson, Liese van Zee, and Amy Winebarger WEDNESDAY ................77 We would like to thank the THURSDAY ................. 143 following sponsors: FRIDAY ......................... 203 Elsevier Northrop Grumman SATURDAY .................. 241 Lockheed Martin The TABASGO Foundation AUTHOR INDEX ........ 242 AAS COUNCIL J. Craig Wheeler Univ. of Texas President (6/2006-6/2008) John P. Huchra Harvard-Smithsonian, President-Elect CfA (6/2007-6/2008) Paul Vanden Bout NRAO Vice-President (6/2005-6/2008) Robert W. O’Connell Univ. of Virginia Vice-President (6/2006-6/2009) Lee W. Hartman Univ. of Michigan Vice-President (6/2007-6/2010) John Graham CIW Secretary (6/2004-6/2010) OFFICERS Hervey (Peter) STScI Treasurer Stockman (6/2005-6/2008) Timothy F. Slater Univ. of Arizona Education Officer (6/2006-6/2009) Mike A’Hearn Univ. of Maryland Pub. Board Chair (6/2005-6/2008) Kevin Marvel AAS Executive Officer (6/2006-Present) Gary J. Ferland Univ. of Kentucky (6/2007-6/2008) Suzanne Hawley Univ. -

The Dispersal of Planet-Forming Discs: Theory Confronts Observations Rsos.Royalsocietypublishing.Org Barbara Ercolano1,2, Ilaria Pascucci3,4

The Dispersal of Planet-forming discs: Theory confronts Observations rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org Barbara Ercolano1;2, Ilaria Pascucci3;4 1Universitäts-Sternwarte München, Scheinerstr. 1, Research 81679 München, Germany 2Excellence Cluster Origin and Structure of the Article submitted to journal Universe, Boltzmannstr.2, 85748 Garching bei München, Germany 3Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, The University of Subject Areas: Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA Astrophysics 4Earths in Other Solar Systems Team, NASA Nexus Keywords: for Exoplanet System Science Protoplanetary Disks, Planet Formation Discs of gas and dust around Myr-old stars are a by-product of the star formation process and provide the raw material to form planets. Hence, their Author for correspondence: evolution and dispersal directly impact what type ercolanousm.lmu.de of planets can form and affect the final architecture of planetary systems. Here, we review empirical constraints on disc evolution and dispersal with special emphasis on transition discs, a subset of discs that appear to be caught in the act of clearing out planet-forming material. Along with observations, we summarize theoretical models that build our physical understanding of how discs evolve and disperse and discuss their significance in the context of the formation and evolution of planetary systems. By confronting theoretical predictions with observations, we also identify the most promising areas for future progress. ............ arXiv:1704.00214v2 [astro-ph.EP] 4 Apr 2017 c 2014 The Authors. Published by the Royal Society under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Pennsylvania Science Olympiad Southeast Regional Tournament 2013 Astronomy C Division Exam March 4, 2013

PENNSYLVANIA SCIENCE OLYMPIAD SOUTHEAST REGIONAL TOURNAMENT 2013 ASTRONOMY C DIVISION EXAM MARCH 4, 2013 SCHOOL:________________________________________ TEAM NUMBER:_________________ INSTRUCTIONS: 1. Turn in all exam materials at the end of this event. Missing exam materials will result in immediate disqualification of the team in question. There is an exam packet as well as a blank answer sheet. 2. You may separate the exam pages. You may write in the exam. 3. Only the answers provided on the answer page will be considered. Do not write outside the designated spaces for each answer. 4. Include school name and school code number at the bottom of the answer sheet. Indicate the names of the participants legibly at the bottom of the answer sheet. Be prepared to display your wristband to the supervisor when asked. 5. Each question is worth one point. Tiebreaker questions are indicated with a (T#) in which the number indicates the order of consultation in the event of a tie. Tiebreaker questions count toward the overall raw score, and are only used as tiebreakers when there is a tie. In such cases, (T1) will be examined first, then (T2), and so on until the tie is broken. There are 12 tiebreakers. 6. When the time is up, the time is up. Continuing to write after the time is up risks immediate disqualification. 7. In the BONUS box on the answer sheet, name the gentleman depicted on the cover for a bonus point. 8. As per the 2013 Division C Rules Manual, each team is permitted to bring “either two laptop computers OR two 3-ring binders of any size, or one binder and one laptop” and programmable calculators. -

![[CII] 158M Emission from L1630 in Orion B](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8802/cii-158m-emission-from-l1630-in-orion-b-1588802.webp)

[CII] 158M Emission from L1630 in Orion B

[CII] 158 µm emission from L1630 in Orion B Cornelia Pabst Leiden Observatory November 29, 2017 in collaboration with: J. R. Goicoechea, D. Teyssier, O. Bern´e,B. B. Ochsendorf, M. G. Wolfire, R. D. Higgins, D. Riquelme, C. Risacher, J. Pety, F. LePetit, E. Roueff, E. Bron, A. G. G. M. Tielens Cornelia Pabst, Leiden Observatory SOFIA tele-talk, November 29, 2017 Introduction PhD student under supervision of Xander Tielens Leiden Observatory, Netherlands Cornelia Pabst, Leiden Observatory SOFIA tele-talk, November 29, 2017 1 / 30 [CII] 158 µm emission [CII] fine-structure line one of the brightest far-infrared cooling lines of the ISM, 1% of total FIR continuum ∼ [CII] line can be observed in distant galaxies correlation of SFR and [CII] intensity: [1] for 46 nearby galaxies, [2] on Galactic scale origin of [CII] emission: dense PDRs, cold HI gas, ionized gas, CO-dark gas on Galactic scale cf. GOT C+ [2] need to spatially resolve the ISM Orion molecular cloud as template region velocity-resolved mapping allows to form a 3D picture [1] Herrera-Camus et al. (2015) ApJ 800:1, [2] Pineda et al. (2014) A&A 570:A121 Cornelia Pabst, Leiden Observatory SOFIA tele-talk, November 29, 2017 2 / 30 The optical window Image Credit: NASA/ESA/Hubble Heritage Team; M. Robberto/Hubble Space Telescope Orion Treasury Project Team Cornelia Pabst, Leiden Observatory SOFIA tele-talk, November 29, 2017 3 / 30 The infrared window Left: visible light. Right: infrared light (IRAS). Image Credit: Akira Fujii/NASA/IRAS Cornelia Pabst, Leiden Observatory SOFIA tele-talk, November 29, 2017 4 / 30 L1630 in the Orion B molecular cloud - visible Alnilam Flame Nebula (NGC 2024) Alnitak NGC 2023 σ Ori Horsehead Nebula IC 434 Image Credit: ESO, Digitized Sky Survey 2 Cornelia Pabst, Leiden Observatory SOFIA tele-talk, November 29, 2017 5 / 30 L1630 in the Orion B molecular cloud - infrared Flame Nebula (NGC 2024) NGC 2023 σ Ori Horsehead Nebula IC 434 Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech (WISE) blue: 3.4 µm, cyan: 4.6 µm, green: 12 µm, red: 22 µm. -

Timescales of the Solar Protoplanetary Disk 233

Russell et al.: Timescales of the Solar Protoplanetary Disk 233 Timescales of the Solar Protoplanetary Disk Sara S. Russell The Natural History Museum Lee Hartmann Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Jeff Cuzzi NASA Ames Research Center Alexander N. Krot Hawai‘i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology Matthieu Gounelle CSNSM–Université Paris XI Stu Weidenschilling Planetary Science Institute We summarize geochemical, astronomical, and theoretical constraints on the lifetime of the protoplanetary disk. Absolute Pb-Pb-isotopic dating of CAIs in CV chondrites (4567.2 ± 0.7 m.y.) and chondrules in CV (4566.7 ± 1 m.y.), CR (4564.7 ± 0.6 m.y.), and CB (4562.7 ± 0.5 m.y.) chondrites, and relative Al-Mg chronology of CAIs and chondrules in primitive chon- drites, suggest that high-temperature nebular processes, such as CAI and chondrule formation, lasted for about 3–5 m.y. Astronomical observations of the disks of low-mass, pre-main-se- quence stars suggest that disk lifetimes are about 3–5 m.y.; there are only few young stellar objects that survive with strong dust emission and gas accretion to ages of 10 m.y. These con- straints are generally consistent with dynamical modeling of solid particles in the protoplanetary disk, if rapid accretion of solids into bodies large enough to resist orbital decay and turbulent diffusion are taken into account. 1. INTRODUCTION chondritic meteorites — chondrules, refractory inclusions [Ca,Al-rich inclusions (CAIs) and amoeboid olivine ag- Both geochemical and astronomical techniques can be gregates (AOAs)], Fe,Ni-metal grains, and fine-grained ma- applied to constrain the age of the solar system and the trices — are largely crystalline, and were formed from chronology of early solar system processes (e.g., Podosek thermal processing of these grains and from condensation and Cassen, 1994).