Teaching Guide: Area of Study 2 – Pop Music Introduction This Resource Is a Teaching Guide for Area of Study 2 (Pop Music) for Our A-Level Music Specification (7272)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daft Punk, La Toile Et Le Disco: Revival Culturel a L'heure Du Numerique

Daft Punk, la Toile et le disco: Revival culturel a l’heure du numerique Philippe Poirrier To cite this version: Philippe Poirrier. Daft Punk, la Toile et le disco: Revival culturel a l’heure du numerique. French Cultural Studies, SAGE Publications, 2015, 26 (3), pp.368-381. 10.1177/0957155815587245. halshs- 01232799 HAL Id: halshs-01232799 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01232799 Submitted on 24 Nov 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. © Philippe Poirrier, « Daft Punk, la Toile et le disco. Revival culturel à l’heure du numérique », French Cultural Studies, août 2015, n° 26-3, p. 368-381. Daft Punk, la Toile et le disco Revival culturel à l’heure du numérique PHILIPPE POIRRIER Université de Bourgogne 26 janvier 2014, Los Angeles, 56e cérémonie des Grammy Awards : le duo français de musique électronique Daft Punk remporte cinq récompenses, dont celle de meilleur album de l’année pour Random Access Memories, et celle de meilleur enregistrement pour leur single Get Lucky ; leur prestation live, la première depuis la sortie de l’album, avec le concours de Stevie Wonder, transforme le Staples Center, le temps du titre Get Lucky, en discothèque. -

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

The Fingerprints of the “5” Royales Nearly 65 Years After Forming in Winston-Salem, the “5” Royales’ Impact on Popular Music Is Evident Today

The Fingerprints of the “5” Royales Nearly 65 years after forming in Winston-Salem, the “5” Royales’ impact on popular music is evident today. Start tracing the influences of some of today’s biggest acts, then trace the influence of those acts and, in many cases, the trail winds back to the “5” Royales. — Lisa O’Donnell CLARENCE PAUL SONGS VOCALS LOWMAN “PETE” PAULING An original member of the Royal Sons, the group that became the The Royales made a seamless transition from gospel to R&B, recording The Royales explored new terrain in the 1950s, merging the raw emotion of In the mid-1950s, Pauling took over the band’s guitar duties, adding a new, “5” Royales, Clarence Paul was the younger brother of Lowman Pauling. songs that included elements of doo-wop and pop. The band’s songs, gospel with the smooth R&B harmonies that were popular then. That new explosive dimension to the Royales’ sound. With his guitar slung down to He became an executive in the early days of Motown, serving as a mentor most of which were written by Lowman Pauling, have been recorded by a sound was embraced most prominently within the black community. Some his knees, Pauling electrified crowds with his showmanship and a crackling and friend to some of the top acts in music history. diverse array of artists. Here’s the path a few of their songs took: of those early listeners grew up to put their spin on the Royales’ sound. guitar style that hinted at the instrument’s role in the coming decades. -

Music Week August 31 1985

MUSIC WEEK AUGUST 31 1985 \ \- MEWS Big Country win News in brief... accounts action THE LIQUIDATOR handling the Gilbert heads new- SCOTS BAND Big Country took affairs of Mountain Records bad their former financial adviser to no prior knowledge that Sahara the High Court last week for Records was to press and distri- allegedly failing to hand over bute the Nazareth albums which royalty statements, tour accounts are now the subject of a copyr- and other documents belonging ight dispute (MW July 27), and look A&R at Arista to the group. only became aware of this after Lodnon-based accountant the event, according to lawyers ARISTA HAS completed distributed through Arista and date UK university and college Keith Moore, who was sacked by acting for the liquidators. the re-structuring of its will go out as the Arista/Rockin' tour. the group in March, gave an HILVERSUM: In the round of ex- Horse label. Gilbert has taken Acting Arista managing direc- undertaking to Mr Justice Scott ecutive moves following the RCA/ A&R department by bring- with him the acts Latin Quarter tor Brian Yates commented; "I to deliver the material not later Ariola merger, Martin Kleinjan ing in former CBS market- and Blue Zone, and members of am delighted to have both Jeff than last Thursday (22). Big has been appointed managing ing director Jeff Gilbert as the Rockin' Horse staff — Sas and the Rockin' Horse label on Country have promised to pay director of RCA/Ariola Benelux. A&R director along with Cooke, Helen Lee and Neil Gib- board. -

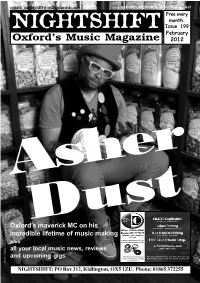

Issue 199.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 199 February Oxford’s Music Magazine 2012 Asher Oxford’sDust maverick MC on his incredible lifetime of music making plus all your local music news, reviews and upcoming gigs. photo: Zahra Tehrani NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net TRUCK FESTIVAL is set to return this summer after founders Robin and Joe Bennett handed the event over to new management. Truck, which had been the centrepiece of Oxford’s live music calendar since 1998, surviving both floods and foot and mouth crises, succumbed to financial woes last year, going into administration in September. However, the event has been taken over by the organisers of Y-Not Festival in Derbyshire, which won Best Grassroots Festival 2011 at the UK Festival Awards. The new organisers hope to take Truck back to its roots as a local community festival. In a statement on the Truck website, Joe and Robin announced, ““We have always felt a great responsibility for the integrity and sustainability of Truck Festival, which grew so quickly and with such enthusiasm from very humble beginnings in 1998. Via Truck’s unique catering arrangements with the Rotary Club, tens of thousands of pounds have been raised for charities and good causes every year, including last year, and many great bands have taken their first steps to international prominence. BONNIE ‘PRINCE’ BILLY makes visits Oxford in May when he “However, after a notoriously difficult summer of trading for Truck teams up with alt.folk band Trembling Bells. -

NARRATIVE EXPERIENCES of SCHOOL COUNSELLORS USING CONVERSATION PEACE, a PEER MEDIATION PROGRAM BASED in RESTORATIVE JUSTICE. By

NARRATIVE EXPERIENCES OF SCHOOL COUNSELLORS USING CONVERSATION PEACE, A PEER MEDIATION PROGRAM BASED IN RESTORATIVE JUSTICE. by HEATHER M. MAIN B.Ed., University of British Columbia, 1982 Dipl.E.C.E., University of British Columbia, 1987 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Counselling Psychology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2008 © Heather M. Main, 2008 11 Abstract This study narratively explores the experiences of five public school counsellors and one high school teacher using Conversation Peace, a restorative action peer mediation program published jointly in 2001 by Fraser Region Community Justice Initiatives Association (CJI), Langley, British Columbia, Canada, and School District #35, Langley, British Columbia, Canada. This categorical-content analysis (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber, 1998) resulted in data describing 20 common themes, 12 with similar responses, and 8 with varying responses amongst participants. Two of the similar findings were the crucial importance of(a) confidentiality within the mediation process, and (b) the school counsellor’s role within the overall and day-to-day implementation of this peer mediation program. Two of the varying findings were (a) the time involvement of the school counsellor within the peer mediation program, and (b) the differences in the number of trained peer mediators and peer mediations within schools. 111 .Table of Contents Abstract ii Table of Contents iii List -

Marvin Gaye As Vocal Composer 63 Andrew Flory

Sounding Out Pop Analytical Essays in Popular Music Edited by Mark Spicer and John Covach The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2010 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2013 2012 2011 2010 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sounding out pop : analytical essays in popular music / edited by Mark Spicer and John Covach. p. cm. — (Tracking pop) Includes index. ISBN 978-0-472-11505-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-472-03400-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Popular music—History and criticism. 2. Popular music— Analysis, appreciation. I. Spicer, Mark Stuart. II. Covach, John Rudolph. ML3470.S635 2010 781.64—dc22 2009050341 Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xi 1 Leiber and Stoller, the Coasters, and the “Dramatic AABA” Form 1 john covach 2 “Only the Lonely” Roy Orbison’s Sweet West Texas Style 18 albin zak 3 Ego and Alter Ego Artistic Interaction between Bob Dylan and Roger McGuinn 42 james grier 4 Marvin Gaye as Vocal Composer 63 andrew flory 5 A Study of Maximally Smooth Voice Leading in the Mid-1970s Music of Genesis 99 kevin holm-hudson 6 “Reggatta de Blanc” Analyzing -

Electrical Hazards and Protecting Persons

Electrical hazards and protecting persons 06 POWER GUIDE 2009 / BOOK 06 ELECTRICAL HAZARDS AND PROTECTING PERSONS The increasing quality of equipment, changes to standards and regulations, and the expertise of specialists have all made electricity the safest type of energy. However, it is still essential to take account of the risks in all projects. Of course, INTRO expertise, common sense, organisation and behaviour will always be the mainstays of safety, but the areas of knowledge required have become so specific and so numerous that the assistance of specialists is often needed. Total protection is never possible and the best safety involves finding reasonable and well thought-out compromises in which priority is given to safeguarding people. The safety of people in relation to the risks identified must be a priority consideration at every step of any project. During the design phase: By complying with installation calculation rules based on the applicable regulations and on each project’s particular features. During the installation phase: By choosing reputable and safe materials and ensuring work is performed correctly. During the operating phase: by defining precise instructions for handling and emergency work, drafting a maintenance plan, and training staff in the tasks they may have to perform (qualifications and authorisations). Risks to people Risk of electric shock � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 02 1� Physiological aspect � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

The BG News March 03, 2021

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 3-3-2021 The BG News March 03, 2021 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation State University, Bowling Green, "The BG News March 03, 2021" (2021). BG News (Student Newspaper). 9156. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/9156 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. bg Raisin’ news An independent student press serving the campus and surrounding community, the Wage ESTABLISHED 1920 Bowling Green State University Wednesday, March 3, 2021 Volume 100, Issue 23 Minimum wage effects on student employees | Page 11 Tree No Leaves Support Volleyball: releases women-owned strong start new album businesses in BG to season Page 5 Page 8 Page 9 PHOTO BY JOSH APPEL VIA UNSPLASH BG-0303-01.indd 1 3/2/21 7:36 PM BG NEWS March 3, 2021 | PAGE 2 Great Selection Close to Campus Great Prices BGSU ON HIGH ALERT JOHN NEWLOVE DHS National Terrorism Announcement REAL ESTATE, INC. Steve Iwanek | Reporter Michigan, and Nation of Islam in Toledo Ohio (not to be mistaken with Masjid of Al- “We are not immune to On Jan. 27 the Department of Homeland Islam Mosque in Toledo). Security announced a domestic terrorism “We are a public institution and people violent behavior in this alert projected to last for weeks. -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

Frühaufsteher 158 Titel, 11,6 Std., 1,02 GB

Seite 1 von 7 -FrühAufsteher 158 Titel, 11,6 Std., 1,02 GB Name Dauer Album Künstler 1 Africa 3:36 Best Of Jukebox Hits - Comp 2005 (CD3-VBR) Laurens Rose 2 Agadou 3:22 Oldies Saragossa Band 3 All american girls 3:57 The Very Best Of - Sister Sledge 1973-93 (RS) Sister Sledge 4 All right now 5:34 Best Of Rock - Comp 2005 (CD1-VBR) Free 5 And the beat goes on 3:26 1000 Original Hits 1980 - Comp 2001 (CD-VBR) The Whispers 6 Another brick in the wall 3:11 Music Of The Millenium II - Comp 2001 (CD1-VBR) Pink Floyd 7 Automatic 4:48 Best Of - The Pointer Sisters - Comp 1995 (CD-VBR) The Pointer Sisters 8 Bad girls 4:55 Bad Girls - Donna Summer - 1979 (RS) Summer Donna 9 Best of my love 3:40 Dutch Collection Earth, Wind & Fire 10 Big bamboo (Ay ay ay) 3:55 Best of Saragossa Band Saragossa Band 11 Billie Jean 4:54 History 1 - Michael Jackson - Comp 1995 (CD-VBR) Jackson Michael 12 Black & white 3:41 Single A Patto 13 Blame it on the boogie 3:35 Good Times - Best Of 70s - Comp 2001 (CD2-VBR) Jackson Five 14 Boogie on reggae woman 4:56 Fulfillingness' First Finale - Stevie Wonder - 1974 (RS) Wonder Stevie 15 Born to be alive 3:09 Afro-Dite Väljer Sina Discofav Hernandez Patrick 16 Break my stride 3:00 80's Dance Party Wilder Matthew 17 Carwash 3:19 Here Come The Girls - Sampler (RS) Royce Rose 18 Celebration 4:59 Mega Party Tracks 06 CD1 - 2001 Kool & The Gang 19 Could it be magic 5:18 A Love Trilogy - Donna Summer - 1976 (RS) Summer Donna 20 Cuba 3:49 Hot & Sunny - Comp 2001 (CD) Gibson Brothers 21 D.I.S.C.O. -

The Fan Data Goldmine Sam Hunt’S Second Studio Full-Length, and First in Over Five Years, Southside Sales (Up 21%) in the Tracking Week

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 24, 2021 Page 1 of 30 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE The Fan Data Goldmine Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debuts at No. 1 on Billboard’s lionBY audienceTATIANA impressions, CIRISANO up 16%). Top Country• Spotify’s Albums Music chart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earnedLeaders 46,000 onequivalent the album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingStreaming to Nielsen Giant’s Music/MRC JessieData. Reyez loves to text, especially with fans.and Ustotal- Countryand Airplay Community No. 1 as “Catch” allows (Big you Machine to do that, Label especially Group) ascends Southside‘Audio-First’ marks Future: Hunt’s seconding No.a phone 1 on the number assigned through the celebrity when you’re2-1, not increasing touring,” 13% says to 36.6Reyez million co-manager, impressions. chart andExclusive fourth top 10. It followstext-messaging freshman LP startup Community and shared on her Mauricio Ruiz.Young’s “Using first every of six digital chart outletentries, that “Sleep you canWith- Montevallo, which arrived at thesocial summit media in No accounts,- the singer-songwriter makes to make sureout you’re You,” stillreached engaging No.