Oral History Interview with I.M. Pei, February 22, 1993

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Table of Contents

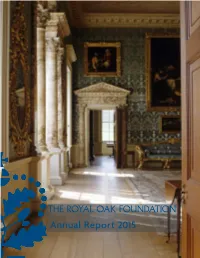

THE ROYAL OAK FOUNDATION Annual Report 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Table of Contents Letter from the Chairman and the Executive Director 2 EXPERIENCE & LEARN Membership 3 Heritage Circle UK Study Day 4 Programs and Lectures 5 Scholarships 6 SUPPORT Grants to National Trust Properties 7-8 Financial Summary 9-10 2015 National Trust Appeal 11 2015 National Trust Appeal Donors 12-13 Royal Oak Foundation Annual Donors 14-16 Legacy Circle 17 Timeless Design Gala Benefit 18 Members 19-20 BOARD OF DIRECTORS & STAFF 22 Our Mission The Royal Oak Foundation inspires Americans to learn about, experience and support places of great historic and natural significance in the United Kingdom in partnership with the National Trust of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. royal-oak.org ANNUAL REPORT 2015 2 THE ROYAL OAK FOUNDATION Americans in Alliance with the National Trust of England, Wales and Northern Ireland September 2016 Dear Royal Oak Community: On behalf of the Royal Oak Board of Directors and staff, we express our continued gratitude to you, our loyal community of members, donors and friends, who help sustain the Foundation’s mission to support the National Trust of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Together, we preserve British history and landscapes and encourage experiences that teach and inspire. It is with pleasure that we present to you the 2015 Annual Report and share highlights from a very full and busy year. We marked our 42nd year as an American affiliate of the National Trust in 2015. Having embarked on a number of changes – from new office space and staff to new programmatic initiatives, we have stayed true to our mission to inspire Americans to learn about, experience, and support places of great historic and natural significance in the UK. -

826 Schermerhorn

826 schermerhorn COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY MIRIAM AND IRA D. WALLACH FINE ARTS CENTER FALL 2020 Dear students, colleagues, and friends, Had I written this text in February, it would have been guided by the same celebratory spirit as those in the past. There has indeed been much to be grateful for in the department. During the 2019–20 academic year, we received extraordinary gifts that allowed the endowment of no fewer than four new professorships. One, from an anonymous donor, honors the legacy of Howard McP. Davis, a famously great teacher of Renaissance art. Messages sent to me from his former students testify to the profound impact he had on them, and I am thrilled that we can commemorate a predecessor in my own field in this way. A second gift, from the Renate, Hans and Maria Hofmann Trust, supports teaching and scholarship in the field of modern American or European art. Our distinguished colleague Kellie Jones has been appointed the inaugural chairholder. A third, donated by the Sherman Fairchild Foundation and named in honor of the foundation’s former president, Walter Burke, will likewise go to a scholar of early modern European art. A search is underway for the first chairholder. Finally, a gift this spring allowed us to complete fundraising for the new Mary Griggs Burke Professorship in East Asian Buddhist Art History. A search for that position will take place next year. Beyond these four new chairs, the department also has two new chairholders: Holger Klein has completed his first year as Lisa and Bernard Selz Professor of Medieval Art History, and Noam Elcott is the inaugural Sobel– Dunn Chair, a title that will henceforth be held by the chair of Art Humanities. -

America's National Gallery Of

The First Fifty Years bb_RoomsAtTop_10-1_FINAL.indd_RoomsAtTop_10-1_FINAL.indd 1 006/10/166/10/16 116:546:54 2 ANDREW W. MELLON: FOUNDER AND BENEFACTOR c_1_Mellon_7-19_BLUEPRINTS_2107.indd 2 06/10/16 16:55 Andrew W. Mellon: Founder and Benefactor PRINCE OF Andrew W. Mellon’s life spanned the abolition of slavery and PITTSBURGH invention of television, the building of the fi rst bridge across the Mississippi and construction of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and Walt Disney’s Snow White, the Dred Scott decision and the New Deal. Mellon was born the year the Paris Exposition exalted Delacroix and died the year Picasso painted Guernica. The man was as faceted as his era: an industrialist, a fi nancial genius, and a philanthropist of gar- gantuan generosity. Born into prosperous circumstances, he launched several of America’s most profi table corporations. A venture capitalist before the term entered the lexicon, he became one of the country’s richest men. Yet his name was barely known outside his hometown of Pittsburgh until he became secretary of the treasury at an age when many men retire. A man of myriad accomplishments, he is remem- bered best for one: Mellon founded an art museum by making what was thought at the time to be the single largest gift by any individual to any nation. Few philan- thropic acts of such generosity have been performed with his combination of vision, patriotism, and modesty. Fewer still bear anything but their donor’s name. But Mellon stipulated that his museum be called the National Gallery of Art. -

Reference Library Faqs

Y A L E C E N T E R F O R B R I T I S H AR T YCBA Reference Library FAQs YCBA Reference Library FAQs 1. What materials are in the YCBA Reference Library? The YCBA Reference Library contains nearly 40,000 titles and over 120 current periodicals devoted to British art, artists, and culture from the sixteenth century to the present day. The collections include essential reference works on British artists, but also contain resources on British architecture, print and book culture, performing arts, costume, town and county histories, and travel books. We also maintain a Photograph Archive, a collection of art conservation and technical analysis materials, as well as videos and DVDs of the Center’s past lectures and programs. There are three public computers available for use, as well as a copier, scanner, printer, microfilm reader, and DVD players. – 2. Can I use the YCBA Reference Library? Yes, the Reference Library is open to researchers of all types: students, scholars, and the general public without an appointment. For more information on specific policies and procedures for using the Reference Library, please see our Policies and Procedures document on our Reference Library and Archives page. – 3. How do I use the YCBA Reference Library? The Reference Library is free and open for use. No appointment is required. Visitors can simply enter the Library on the second floor and sign in to our Guest Book. – 4. Can I check out books from the YCBA Ref Lib? No. The Reference Library is a non-circulating library; however, we do have a scanner and copier located within the library for use. -

Press Release

Press Contacts Cara Egan PRESS Seattle Art Museum P.R. [email protected] 206.748.9285 RELEASE Wendy Malloy Seattle Art Museum P.R. [email protected] JULY 2015 206.654.3151 INTIMATE IMPRESSIONISM FROM THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART OPENS AT THE SEATTLE ART MUSEUM OCT 1, 2015 October 1, 2015–January 10, 2016 SEATTLE, WA – Seattle Art Museum (SAM) presents Intimate Impressionism from the National Gallery of Art, featuring the captivating work of 19th-century painters such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh. The exhibition includes 71 paintings from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and features a selection of intimately scaled Impressionist and Post-Impressionist still lifes, portraits and landscapes, whose charm and fluency invite close scrutiny. “This important exhibition is comprised of extraordinary paintings, among the jewels of one of the finest collections of French Impressionism in the world,” says Kimerly Rorschach, Seattle Art Museum’s Illsley Ball Nordstrom Director and CEO. “We are pleased to host these national treasures and provide our audience with the opportunity to enjoy works by Impressionist masters that are rarely seen in Seattle.” Seattle is the last opportunity to view this exhibition following an international tour that included Ara Pacis Museum of the Capitoline Museums, Rome; Fine Arts Museums in San Francisco; McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, and Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum, Tokyo. The significance of this exhibition is grounded in the high quality of each example and in the works’ variety of subject matter. The paintings’ dimensions reflect their intended function: display in domestic interiors. -

Signatories of Letter to CSU Chancellor Charles Reed

Signatories of Letter to CSU Chancellor Charles Reed February 6, 2012 Prescott Watson Santa Cruz CA Tammi Benjamin Santa Cruz CA Guy Herschmann Santa Cruz CA Clare Capsuto Santa Cruz CA Adrianne Gibilisco Chapel Hill NC JAMES HEBERT ST LOUIS MO Helene Fine West Hills CA Ben Goldman Hartford CT Chad Miller Mountain Virw CA Alan Feinstein Napa CA Sheree Roth Palo Alto CA Susan Tucker Thousand Oaks CA Ingreid Hansen New York NY Shlomo Frieman Los Angeles CA Jay Saadian Los Angeles CA Stanley Levine Calabasas CA Barnoy Irvine CA Ilan Benjamin Santa Cruz CA Linda Rothfield San Francisco CA Hannah Scholl Los Angeles CA Fred Weinberger Englewood NJ Marsha Roseman Van Nuys CA Andrea Grant Oakland CA Steve Bennet Palo Alto CA Louise Miller La Jolla CA Ken Cosmer MD Agoura Hills CA daniel greenblatt ashland OR Jenny Kupperstein Orange CA Dr. Steven Bein Los Angeles CA Daniel Spitzer, Ph.D. Berkeley CA Jacqueline Elkins Hidden Hills CA Ruth Goldstine El Granada CA Elaine Hogan Cupertino CA Bruce Kesler Encinitas CA jerome n. lederer santa monica CA Wynne and Mark Trinca East Amherst NY Anya Kagan San Jose CA Natalie Wallach Montville NJ William Frank Berkeley CA Marlene G. Smith Roseville CA Signatories of Letter to CSU Chancellor Charles Reed February 6, 2012 Harriet Wolpoff San Diego CA Orit Sherman Oaks CA Yitzchok Pinkesz Brooklyn NY Jack F. Berkowitz Goshen NY Barry F. Chaitin Newport Beach CA ALAN NISHBALL IRVINE CA Bee Epstein-Shepherd Carmel CA Charles Geshekter Chico CA Mitch Danzig Encinitas CA Itzhak Bars Arcadia CA Avromi Apt Palo Alto CA Rachel Humphrey El Cerrito CA Andrew Viterbi Rancho Santa Fe CA Daniel Cohen Sacramento CA Rachel Neuwirth Los Angeles CA Nora Straight Surfside CA John Belsher San Luis Obispo CA Gordon Rosen Montebello NY BARBARA ANN NORTON WHEATON IL Karen Richter Culver City CA Alvin D. -

Henry A. Millon

A LIFE OF LEARNING Henry A. Millon Charles Homer Haskins Lecture for 2002 American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 54 ISSN 1041-536X © 2002 by Henry A. Millon A LIFE OF LEARNING Henry A. Millon Charles Homer Haskins Lecture for 2002 American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 54 The Charles Homer Haskins Lecture Charles Homer Haskins (1870-1937), for whom the ACLS lecture series is named, was the first Chairman of the American Council of Learned Societies, from 1920 to 1926. He began his teaching career at the Johns Hopkins University, where he received the B.A. degree in 1887, and the Ph.D. in 1890. He later taught at the University of Wisconsin and at Harvard, where he was Henry Charles Lea Professor of Medieval History at the time of his retirement in 1931, and Dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences from 1908 to 1924. He served as president of the American Historical Association in 1922, and was a founder and the second president of the Medieval Academy of America in 1926. A great American teacher, Charles Homer Haskins also did much to establish the reputation of American scholarship abroad. His distinction was recognized in honorary degrees from Strasbourg, Padua, Manchester, Paris, Louvain, Caen, Harvard, Wisconsin, and Allegheny College, where in 1883 he had begun his higher education at the age of thirteen. Previous Haskins Lecturers 1983 Maynard Mack 1984 Mary Rosamond Haas 1985 Lawrence Stone 1986 Milton V. Anastos 1987 Carl E. Schorske 1988 John Hope Franklin 1989 Judith N. -

AAR Magazine

AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME MAGAZINE SPRING 2017 Welcome to the Spring 2017 issue of AAR Magazine. This issue of AAR Magazine offers a summation of a very productive year. We feature the scholars and artists in our creative community at the culmination of their research and look at how the Fellows’ Project Fund has expanded their possibilities for collaborat- ing and presenting their work in intriguing ways. We update this year’s exploration of American Classics with reports on a February conference and previews of events still to come, including an exhibition fea- turing new work by artist Charles Ray. You will also find a close look at AAR’s involvement in archaeology and details of a new Italian Fellowship sponsored by Fondazione Sviluppo e Crescita CRT. And, of course, we introduce the Rome Prize win- ners and Italian Fellows for 2017–2018! Vi diamo il benvenuto al numero “Primavera 2017” dell’AAR Magazine. Questo numero dell’AAR Magazine riassume il lavoro prodotto in un anno eccezionale. Vi presentiamo gli studiosi e gli artisti della nostra comunità creativa al culmine della loro ricerca e siamo lieti di mostrare quanto il Fellows’ Project Fund abbia ampliato le loro possibilità di collaborare e presentare le proprie opere in modo affascinante. Aggiorniamo la pan- oramica fatta quest’anno sugli American Classics con il resoconto del convegno tenutosi a febbraio e con le anticipazioni sui prossimi eventi, tra i quali una mostra con una nuova opera dell’artista Charles Ray. Daremo uno sguardo da vicino all’impegno dell’AAR nel campo dell’archeologia e alla nuova Borsa di studio per Italiani finanziata da Fondazione Sviluppo e Crescita CRT. -

WINTER 2008 Quarterly

1932c3.qxd:Layout 1 4/8/08 9:28 AM Page 1 PublicPublicHealthUNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH GRADUATEHealth SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH WINTER 2008 Quarterly 2007 Year in Review: 60 Things Everyone Should Know About GSPH 1932c3.qxd:Layout 1 4/8/08 9:28 AM Page 2 Winter 2008 In this issue... Dean’s Message . .1 Students: Student Events . .6 Legacy Laureate Alumni . .8 Luncheon Faculty Research . .10 7 Faculty Honors . .12 Books by Faculty . .14 Centers News . .16 Development . .18 Faculty Research: Recent Events . .22 National Children’s Study 10 Books by Faculty: Unequal 14 Opportunity Centers News: 16 Center for Minority Health PublicHealth University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health Co-Editors Design For inquiries, feedback, Linda Fletcher Vance Wright Adams or comments, please contact: Gina McDonell Gina McDonell Printing 412-648-1294 Circulation Manager Hoechstetter [email protected] Jill Ruempler PublicHealth Quarterly is published four times per year for the alumni and friends of the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health. PublicHealth Quarterly is printed on recycled paper using vegetable-based inks. 1932c3.qxd:Layout 1 4/8/08 9:28 AM Page 1 Dean’s Message A Message from the Dean Donald S. Burke, MD This issue of PublicHealth Quarterly looks back at the year that was in 2007 at the Graduate School of Public Health. Because 2008 marks the 60th anniversary of the founding of GSPH, we bring you 60 gems from this past year — metaphorical candles on the school’s birthday cake, if you will. Join with me in offering hearty congratulations to everyone involved with these achievements, realizing that they represent only a glimpse of what we can accomplish. -

Middleburg 109

HOSTED BY THE FAUQUIER AND LOUDOUN GARDEN CLUB Middleburg 109 THE REGULAR TOUR TICKET INCLUDES ADMISSION TO THE FOLLOWING 3 LOCATIONS: White Hall, 6551 Main Street, tural styles. Composed of six separate inter- The Plains connected structures, the home is elevated six inches off exterior grade, creating a Nestled in the charming village of The unique symbiotic integration of exterior Plains, this stately and picturesque Greek and interior space. Seven walkable garden Revival house, until it was purchased and areas, in addition to plantings and landscap- renovated by the current owners in 2018, ing, surround the residence. The entrance had been in the same family since it was to the gardens is through a folly into an in- built in 1903. Originally a wood frame timate garden foyer, off of which are the house, the structure was covered in stucco north and south garden chambers, each in the early 20th century then overlaid with an arched entrance. A distant westward with brick by mid-century. Portions from view reveals a Palladian-style entry pavilion each stage are still exposed. White Hall facing a reflecting pool surrounded by Photo courtesy of Missy Janes and Elysian Fields embraces neoclassical elements of design, including a graceful front portico, tower- woody and herbaceous plantings and two ing columns and a grand foyer stretching allées of pear trees. From the path border- the length of the house. It also boasts 12- ing the reflecting pool, there are distant foot ceilings, original floors, plaster and westerly views through the glass connectors wood molding, original plaster walls and on either side of the entry pavilion. -

BSI3003 Fall07 9/24/07 12:41 PM Page A

BSI3003_Fall07 9/24/07 12:41 PM Page a A Publication of Building Stone Institute Fall 2007 VVolumeolume 30, Number 3 THE ART OF STONE CARVING Carved Creations An Eye for Detail Granite Opens a World of Possibilities BSI FullPage Template 6/14/07 11:32 AM Page 1 BSI FullPage Template 9/7/07 2:47 PM Page 1 BSI3003_Fall07 9/20/07 1:18 PM Page 2 Fall 2007 Volume 30 • Number 3 Contents 8 Photo courtesy of Harold C. Vogel Features Departments 8 A Cut Above: The Art 6 Introduction of Stone Carving Historical Feature Carvers and sculptors who find the “inner being” of natural stone 72 Modern Icon on work their magic to add beauty and definition to homes, parks and structures. Author Mark Haverstock highlights some of the best and the Mall brightest artisans in the United States. Read about their passions and The East Building of the see photographs of some of their finest works. National Gallery of Art, now almost 30 years old, features public and private spaces that are celebrated 22 Carved Creations internationally as both con- Monuments, fountains and sculptures are just some of the creations that struction marvel and sculpture. arise from natural stone. Here, see prime examples of art that adds a touch of class – and sometimes whimsy – to the great outdoors. 76 Industry News On the Cover: 30 Frequently Asked Questions: 80 Advertising Index Stone: Blanco Limon. St. Regis Hotel and Resort, Stone Sculpting and Carving Monarch Beach, Calif. Sit down with an expert stone carver who shares his perspectives on some of the questions we’re most often asked here at Photo courtesy of Building Stone Magazine. -

Red Bank Area J Row

Weather Dutribottoa Today .__ nutsy after morning THEDAILY ckxtdlnesi toddy. On &e cool •Me today and tonight High In 26,925 mid or upper 60s and low In up- per 4ts. Fair and milder tomor- Red Bank Area J row. High around 70. Friday's Copyright—The Red Bank Register, Inc. M66. outlook, cloudy and mild. DIAL 7414)010 MONMOUTH COUNTY'S HOME NEWSPAPER FOR 88 YEARS biucd dally. Uondir tfcroufh Frldiy. Second Clua Pottagt WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 12, 1966 VOL. 89, NO. 75 Pi.ll IX Red Bank and it Additional MiMul Offices. 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE Drug Problem Needs Many Attacks, Psychiatrist Says By JACQUELINE ALBAN cussion sponsored by Joseph had alerted communities to drug drug rehabilitation program has tients to remain at Skillman long going medical and psychiatric Panelist P. Paul Campi, Mon- nevertheless declared: "I've been LONG BRANCH — "We've Finkel Lodge of Bnai Brith. abusers in their areas for fu- to be a severe one, with patients enough to receive therapy, con- treatment. As a result of attacks, mouth County Undersheriff, last reading about a Narcotics Com- reached the stage in drug ad- The psychiatrist was asked why ture surveillance; had helped save forced to remain for a longer pe- tending that SO per cent of so- the state Department of Institu- night called on this county to mission being formed to study diction where it's imperative to federal drug treatment centers in or prolong lives, and kept ad- riod of time than just a few days called rehabilitation time is spent tions and Agencies is consider- "get moving On this program so the narcotics problem here.