Letterhead Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lots of Glass, Not Enough Cash

BROOKLYN’S REAL NEWSPAPERS Including The Bensonhurst Paper Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2006 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 12 pages •Vol. 29, No. 1 BWN • Saturday, January 7, 2006 • FREE THE NEW BROOKLYN PUBLIC LIBRARY LOTS OF GLASS, NOT ENOUGH CASH / Julie Rosenberg The Brooklyn Papers The Brooklyn Babies of the New Year are here! Enrique Norten / TEN Arquitectos A rendering of the proposed Brooklyn Public Library Visual and Performing Arts branch (right) at Flatbush and Lafayette avenues in Fort Greene, next to the proposed Frank Gehry-designed Theatre for a New Audience (center). The two buildings would stand next to the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Neo-Itlaianate structure (left). By Ariella Cohen To jumpstart the latest fundraising in serious doubt. poration, while another $3 million “It is very seductive and appeal- The Brooklyn Papers campaign, on Tuesday, the library “In a perfect world, we are talking was given by the City Council and ing, but you have to ask some hard had Norten show off tweaks in his about building in the next four or directly from the Bloomberg admin- questions about how a project like The building is clear, but who well-received design to the library’s five years,” said Cooper. “But we stration. Another $2 million came this will be subsidized and sus- will pay for it remains murky. board of trustees. have to find funding first.” from Albany. tained,” said Marilyn Gelber, execu- Brooklyn Public Library admitted The project’s glistening architec- Raising money for projects in Down- Part of Norten’s presentation was tive director of Independence Com- last week that it is struggling to raise tural benchmarks remain, but now town Brooklyn — even ones attached simply to remind the library board of munity Bank Foundation. -

106Th Congpicdir New York

NEW YORK Sen. Daniel P. Moynihan Sen. Charles E. Schumer of Oneonta of Brooklyn Democrat—Jan. 3, 1977 Democrat—Jan. 6, 1999 Michael Forbes Rick A. Lazio of Quogue (1st District) of Brightwaters (2d District) Republican—3d term Republican—4th term 90 NEW YORK Peter T. King Carolyn McCarthy of Seaford (3d District) of Mineola (4th District) Republican—4th term Democrat—2d term Gary L. Ackerman Gregory Meeks of Queens (5th District) of Far Rockaway (6th District) Democrat—9th term Democrat—1st term 91 NEW YORK Joseph Crowley Jerrold Nadler of Queens (7th District) of New York City (8th District) Democrat—1st term Democrat—5th term Anthony Weiner Edolphus Towns of Brooklyn (9th District) of Brooklyn (10th District) Democrat—1st term Democrat—9th term 92 NEW YORK Major R. Owens Nydia M. Velázquez of Brooklyn (11th District) of Brooklyn (12th District) Democrat—9th term Democrat—4th term Vito Fossella Carolyn B. Maloney of Staten Island (13th District) of New York City (14th District) Republican—1st term Democrat—4th term 93 NEW YORK Charles B. Rangel José E. Serrano of New York City (15th District) of Bronx (16th District) Democrat—15th term Democrat—6th term Eliot L. Engel Nita M. Lowey of Bronx (17th District) of Harrison (18th District) Democrat—6th term Democrat—6th term 94 NEW YORK Sue Kelly Benjamin A. Gilman of Katonah (19th District) of Middletown (20th District) Republican—3d term Republican—14th term Michael R. McNulty John Sweeney of Green Island (21st District) of Schaghticoke (22d District) Democrat—6th term Republican—1st term 95 NEW YORK Sherwood L. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions Of

E2104 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks October 10, 2007 they are doing in Missouri. Congratulations on RECOGNIZING HON. JOHN THOMAS doctors believed he had recovered, Sebastian an outstanding achievement. ELFVIN went to the gym for his regular workout, during which he suffered sudden cardiac arrest and f HON. BRIAN HIGGINS nearly died. Thanks to a quick acting response OF NEW YORK team that shocked his heart back to its normal HONORING MAURICE KENNETH IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES rhythm, Sebastian was literally brought back to SHAW OF MIDDLETOWN, NJ life. Wednesday, October 10, 2007 Sebastian is one of the few lucky ones to Mr. HIGGINS. Madam Speaker, I rise today live through a deadly sudden cardiac arrest HON. VITO FOSSELLA to pay recognition to the Honorable John event. We in Washington have made great OF NEW YORK Thomas Elfvin, who is retiring after 60 years of strides fighting some of our Nation’s deadliest IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES service as a judge in the U.S. District Court for killers. Our next step should be to commit to Western New York. Judge Elfvin has dem- more research into the diagnosis, prevention, Wednesday, October 10, 2007 onstrated exemplary dedication throughout his and treatment of sudden cardiac arrest, includ- Mr. FOSSELLA. Madam Speaker, I rise career, serving diligently until the age of 90. ing increased awareness efforts to improve today to honor the life and achievements of I would like briefly to touch on the many public knowledge of at-risk populations. We Maurice Kenneth Shaw of Middletown, NJ, areas of service that Judge Elfvin gave to our also must take steps to improve access to who died Sunday afternoon in Riverview Hos- county. -

Report on HELLENIC ISSUES

Report on HELLENIC ISSUES Congressional Caucus on Hellenic Issues History and Accomplishments A Progress Report from the Office of Rep. Carolyn B. Maloney Table of Contents I. Statement of Purpose II. Bills Introduced in the 112th Congress III. Bills Introduced in the 111th Congress IV. Bills Introduced in the 110th Congress V. Bills Introduced in the 109th Congress VI. Bills Introduced in the 108th Congress VII. Bills Introduced in the 107th Congress VIII. Bills Introduced in the 106th Congress IX. Bills Introduced in the 105th Congress X. Bills Introduced in the 104th Congress XI. Accomplishments - Bills Enacted XII. Passed House and/or Senate XIII. Letters XIV. Statements XV. Other Hellenic Caucus Activities th XVI. Members - 112 Congress I. STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Established in 1996, the Congressional Caucus on Hellenic Issues works to foster and improve relations between the United States and Greece. The Caucus brings a renewed congressional focus on key diplomatic, military, and human rights issues in a critical part of the world. The members of the Caucus introduce legislation, arrange briefings on current events, and disseminate information to interested parties. The topics on which the Caucus focuses include U.S. aid to Greece and Cyprus, the conflict in Cyprus, U.S. relations with the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, the status of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, and developments in the Aegean. In the 112th Congress, the Caucus has more than 135 members. II. BILLS INTRODUCED IN THE 112th CONGRESS H. Res. 650 Expressing the sense of the House of Representatives that the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia should work within the framework of the United Nations process with Greece to achieve longstanding United States and United Nations policy goals of finding a mutually acceptable name, for all uses, for the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. -

Extensions of Remarks E2104 HON. VITO FOSSELLA HON. BRIAN

E2104 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks October 10, 2007 they are doing in Missouri. Congratulations on RECOGNIZING HON. JOHN THOMAS doctors believed he had recovered, Sebastian an outstanding achievement. ELFVIN went to the gym for his regular workout, during which he suffered sudden cardiac arrest and f HON. BRIAN HIGGINS nearly died. Thanks to a quick acting response OF NEW YORK team that shocked his heart back to its normal HONORING MAURICE KENNETH IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES rhythm, Sebastian was literally brought back to SHAW OF MIDDLETOWN, NJ life. Wednesday, October 10, 2007 Sebastian is one of the few lucky ones to Mr. HIGGINS. Madam Speaker, I rise today live through a deadly sudden cardiac arrest HON. VITO FOSSELLA to pay recognition to the Honorable John event. We in Washington have made great OF NEW YORK Thomas Elfvin, who is retiring after 60 years of strides fighting some of our Nation’s deadliest IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES service as a judge in the U.S. District Court for killers. Our next step should be to commit to Western New York. Judge Elfvin has dem- more research into the diagnosis, prevention, Wednesday, October 10, 2007 onstrated exemplary dedication throughout his and treatment of sudden cardiac arrest, includ- Mr. FOSSELLA. Madam Speaker, I rise career, serving diligently until the age of 90. ing increased awareness efforts to improve today to honor the life and achievements of I would like briefly to touch on the many public knowledge of at-risk populations. We Maurice Kenneth Shaw of Middletown, NJ, areas of service that Judge Elfvin gave to our also must take steps to improve access to who died Sunday afternoon in Riverview Hos- county. -

5932 Hon. Michael E. Capuano Hon. Vito Fossella

5932 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS, Vol. 153, Pt. 4 March 8, 2007 American causes, many of the immigrants are his father.’ My husband couldn’t speak, fort Women, of which I am a proud co-spon- hesitated, said Bing Cardenas Branigin, 50, a but I could tell that he understood, because sor. Given recent events, the necessity and former regional chairman of the Filipino there were tears in his eyes.’’ imperative to pass H. Res. 121 by the full American federation. Now Romulo worries that her son may ‘‘There was this sense that you shouldn’t never gain entry to the United States, be- House of Representatives is now more impor- make trouble, that you shouldn’t contradict cause if a sponsor dies while the visa applica- tant than ever. It is my hope that this non- the government,’’ she said. ‘‘You should just tion is pending, there is a chance that the binding resolution will signal to our friend and pay your taxes and send your kids to school application will be annulled. ally, the Government of Japan, that working to and keep quiet.’’ But she said she is still praying that Con- officially resolve its longstanding historical That began to change in the mid-1970s gress will pass the legislation for the sake of issues will not only restore honor and dignity when anger spread over the repressive poli- those veterans who remain alive. to the Comfort Women survivors, but bring out cies of the Filipino president, Ferdinand ‘‘If that happens, I know my husband will greater trust and cooperation among our other Marcos. -

New Jersey: Jon Corzine (D) (Open Seat)

EMBARGOED UNTIL OCTOBER 5, 2000 Contact: Travis Plunkett (202) 387-6121 CONSUMER FEDERATION OF AMERICA PAC ENDORSES CONGRESSIONAL CHALLENGERS WASHINGTON, D.C. -- Consumer Federation of America PAC today announced its political action committee’s endorsement of non-incumbent candidates for the 2000 House and Senate races. The candidates--4 in the Senate and 19 in the House of Representatives--were chosen from open seat races and challengers to those incumbents with poor consumer voting records. “After reviewing positions of these candidates, CFA PAC is confident that they will defend the consumer interest if elected,” said Travis Plunkett, CFA’s Legislative Director. Endorsements of challengers and candidates in open races are based on an evaluation of responses to a candidate questionnaire. For challengers, CFA PAC also considers the consumer voting record of the incumbent they are challenging. CFA evaluates the challenger’s voting record if the challenger has served in the U.S. House of Representatives or the U.S. Senate. “Consumer issues have taken center stage in Washington. In poll after poll, Americans rank consumer issues among their top concerns. These candidates have expressed strong pro-consumer views on issues such as personal privacy, product and food safety, managed care patient protections, and predatory lending. We support their candidacy,” he concluded. (See attached list of key consumer issues to date during the 106th Congress.) * * * 2000 CHALLENGERS AND OPEN RACES Senate New Jersey: Jon Corzine (D) (Open Seat) Pennsylvania: -

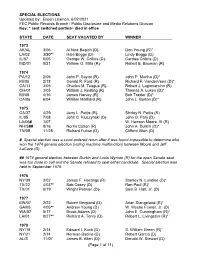

Special Election Dates

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

108Th Congressional Pictorial Directory

NEW YORK Sen. Charles E. Schumer Sen. Hillary Rodham of Brooklyn Clinton Democrat—Jan. 6, 1999 of Chappaqua Democrat—Jan. 3, 2001 Timothy H. Bishop Steve Israel of Southampton (1st District) of Huntington (2d District) Democrat—1st term Democrat—2d term 93 NEW YORK Peter T. King Carolyn McCarthy of Seaford (3d District) of Mineola (4th District) Republican—6th term Democrat—4th term Gary L. Ackerman Gregory W. Meeks of Jamaica Estates (5th District) of Queens (6th District) Democrat—11th term Democrat—4th term 94 NEW YORK Joseph Crowley Jerrold Nadler of Queens/Bronx (7th District) of New York (8th District) Democrat—3d term Democrat—7th term Anthony D. Weiner Edolphus Towns of Brooklyn (9th District) of Brooklyn (10th District) Democrat—3d term Democrat—11th term 95 NEW YORK Major R. Owens Nydia M. Velázquez of Brooklyn (11th District) of Brooklyn (12th District) Democrat—11th term Democrat—6th term Vito Fossella Carolyn B. Maloney of Staten Island (13th District) of New York (14th District) Republican—4th term Democrat—6th term 96 NEW YORK Charles B. Rangel José E. Serrano of New York (15th District) of Bronx (16th District) Democrat—17th term Democrat—8th term Eliot L. Engel Nita M. Lowey of Bronx (17th District) of Harrison (18th District) Democrat—8th term Democrat—8th term 97 NEW YORK Sue W. Kelly John E. Sweeney of Katonah (19th District) of Clifton Park (20th District) Republican—5th term Republican—3d term Michael R. McNulty Maurice D. Hinchey of Green Island (21st District) of Saugerties (22d District) Democrat—8th term Democrat—6th term 98 NEW YORK John M. -

Union Calendar No. 478 105Th Congress, 2D Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 105–837

1 Union Calendar No. 478 105th Congress, 2d Session ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± House Report 105±837 SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES A REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON BANKING AND FINANCIAL SERVICES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION DECEMBER 31, 1998.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 69±006 WASHINGTON : 1999 COMMITTEE ON BANKING AND FINANCIAL SERVICES One Hundred Fifth Congress JAMES A. LEACH, Iowa, Chairman BILL MCCOLLUM, Florida HENRY B. GONZALEZ, Texas MARGE ROUKEMA, New Jersey JOHN J. LAFALCE, New York DOUG BEREUTER, Nebraska BRUCE F. VENTO, Minnesota RICHARD H. BAKER, Louisiana CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York RICK LAZIO, New York BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts SPENCER BACHUS, Alabama PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania MICHAEL CASTLE, Delaware JOSEPH P. KENNEDY II, Massachusetts PETER T. KING, New York FLOYD H. FLAKE, New York 10 TOM CAMPBELL, California MAXINE WATERS, California EDWARD R. ROYCE, California CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois JACK METCALF, Washington LUCILLE ROYBAL-ALLARD, California ROBERT W. NEY, Ohio THOMAS M. BARRETT, Wisconsin ROBERT L. EHRLICH, Maryland NYDIA M. VELAÂ ZQUEZ, New York BOB BARR, Georgia MELVIN WATT, North Carolina JON D. FOX, Pennsylvania MAURICE HINCHEY, New York FRANK LOBIONDO, New Jersey 1 GARY ACKERMAN, New York J.C. WATTS, JR., Oklahoma 2 KEN BENTSEN, Texas SUE KELLY, New York JESSE JACKSON, JR., Illinois RON PAUL, Texas CYNTHIA MCKINNEY, Georgia 6 DAVE WELDON, Florida CAROLYN CHEEKS KILPATRICK, Michigan JIM RYUN, Kansas JAMES H. MALONEY, Connecticut MERRILL COOK, Utah DARLENE HOOLEY, Oregon VINCE SNOWBARGER, Kansas JULIA M. -

Union Calendar No. 472 105Th Congress, 2D Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 105–831

Union Calendar No. 472 105th Congress, 2d Session ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± House Report 105±831 (105±89) SUMMARY OF LEGISLATIVE AND OVERSIGHT ACTIVITIES ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Convened JANUARY 7, 1997 Adjourned NOVEMBER 13, 1997 SECOND SESSION Convened JANUARY 27, 1998 Adjourned OCTOBER 21, 1998 COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES December 17, 1998.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE ★69±006 WASHINGTON : 1998 COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE BUD SHUSTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman DON YOUNG, Alaska JAMES L. OBERSTAR, Minnesota THOMAS E. PETRI, Wisconsin NICK J. RAHALL, II, West Virginia SHERWOOD L. BOEHLERT, New York ROBERT A. BORSKI, Pennsylvania HERBERT H. BATEMAN, Virginia WILLIAM O. LIPINSKI, Illinois HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina ROBERT E. WISE, JR., West Virginia JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee JAMES A. TRAFICANT, JR., Ohio SUSAN MOLINARI, New York4 PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon THOMAS W. EWING, Illinois BOB CLEMENT, Tennessee WAYNE T. GILCHREST, Maryland JERRY F. COSTELLO, Illinois JAY KIM, California GLENN POSHARD, Illinois STEPHEN HORN, California ROBERT E. (BUD) CRAMER, JR., Alabama7 BOB FRANKS, New Jersey ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JOHN L. MICA, Florida Columbia JACK QUINN, New York JERROLD NADLER, New York TILLIE K. FOWLER, Florida PAT DANNER, Missouri VERNON J. EHLERS, Michigan ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey SPENCER BACHUS, Alabama JAMES E. CLYBURN, South Carolina STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio CORRINE BROWN, Florida SUE W. KELLY, New York JAMES A. BARCIA, Michigan RAY LAHOOD, Illinois BOB FILNER, California RICHARD H. BAKER, Louisiana EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON, Texas FRANK RIGGS, California FRANK MASCARA, Pennsylvania CHARLES F. -

110Th Congress Congressional Pictorial

NEW YORK Sen. Charles E. Schumer Sen. Hillary Rodham of Brooklyn Clinton Democrat—Jan. 6, 1999 of Chappaqua Democrat—Jan. 3, 2001 Rep. Timothy H. Bishop Rep. Steve Israel of Southampton (1st District) of Huntington (2d District) Democrat—3 terms Democrat—4 terms 93 Senate LeadershipCDV1.indd 93 6/4/07 8:47:45 AM NEW YORK Rep. Peter T. King Rep. Carolyn McCarthy of Seaford (3d District) of Mineola (4th District) Republican—8 terms Democrat—6 terms Rep. Gary L. Ackerman Rep. Gregory W. Meeks of Jamaica Estates of Queens (6th District) (5th District) Democrat—6 terms Democrat—13 terms 94 Senate LeadershipCDV1.indd 94 6/4/07 8:47:46 AM NEW YORK Rep. Joseph Crowley Rep. Jerrold Nadler of Queens/Bronx (7th District) of New York (8th District) Democrat—5 terms Democrat—9 terms Rep. Anthony D. Weiner Rep. Edolphus Towns of Brooklyn (9th District) of Brooklyn (10th District) Democrat—5 terms Democrat—13 terms 95 Senate LeadershipCDV1.indd 95 6/4/07 8:47:46 AM NEW YORK Rep. Yvette D. Clarke Rep. Nydia M. Velázquez of Brooklyn (11th District) of Brooklyn (12th District) Democrat—1 term Democrat—8 terms Rep. Vito Fossella Rep. Carolyn B. Maloney of Staten Island (13th District) of New York (14th District) Republican—6 terms Democrat—8 terms 96 Senate LeadershipCDV1.indd 96 6/4/07 8:47:47 AM NEW YORK Rep. Charles B. Rangel Rep. José E. Serrano of New York (15th District) of Bronx (16th District) Democrat—19 terms Democrat—10 terms Rep. Eliot L. Engel Rep. Nita M.