Zababdeh: a Palestinian Water History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’S First Decades

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’s First Decades Rotem Erez June 7th, 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Stefan Kipfer A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Student Signature: _____________________ Supervisor Signature:_____________________ Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................9 Chapter 1: A Comparative Study of the Early Years of Colonial Casablanca and Tel-Aviv ..................... 19 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 19 Historical Background ............................................................................................................................ -

History of Israel

History of Israel FALL-Tuesday and Thursday, 9:30–10:45, CBA 4.340 Course Description Israel is a country of contrasts. Merely 263 miles long, one can drive from its northernmost point to the southernmost one in six hours, passing by a wide variety of landscapes and climates; from the snowy capes of Mount Hermon to the arid badlands of the Negev Desert. Along the way, she might come across a plethora of ethnic and religious groups – Jews originating in dozens of diasporas all over the world, Palestinians, Druze, Bedouins, Bahá'ís, Samaritans, Circassians, Armenians, Gypsies, Filipinos, Sudanese, Eritreans, and more – and hear innumerable languages and dialects. From the haredi stronghold of Bene-Beraq to the hedonistic nightclubs and sunny beaches of Eilat; from a relative Jewish-Arab coexistence in Haifa to the powder keg that is East Jerusalem; from the “Start-up Nation” in Ra’anana and Herzliya to the poverty-stricken “development towns” and unrecognized Bedouin settlements of the Negev; from the messianic fervor of Jewish settlers in the West Bank to the plight of African refugees and disadvantaged Jews in South Tel Aviv – all within an area slightly smaller than the State of Vermont. This is an introductory survey of Israel’s political, diplomatic, social, economic, ethnic, and cultural history, as well as an overview of Israeli society nowadays. We will start with a brief examination of the birth of the Zionist movement in nineteenth-century Europe, the growth of the Jewish settlement in Palestine, and the establishment of a modern Jewish State. Next, we will review a number of key moments and processes in Israeli history and discuss such crucial and often controversial topics as the Israeli-Arab and Israeli-Palestinian conflicts; ethnic and social stratification in Israel; civil-military relations and the role that the armed forces and other security agencies have played in everyday life in the country; Israel’s relations with the world and the Jewish diaspora; and more. -

OH-00143; Aaron C. Kane and Sarah Taylor Kane

Transcript of OH-00143 Aaron C. Kane and Sarah Taylor Kane Interviewed by John Wearmouth on February 19, 1988 Accession #: 2006.034; OH-00143 Transcribed by Shannon Neal on 10/15/2020 Southern Maryland Studies Center College of Southern Maryland Phone: (301) 934-7626 8730 Mitchell Road, P.O. Box 910 E-mail: [email protected] La Plata, MD 20646 Website: csmd.edu/smsc The Stories of Southern Maryland Oral History Transcription Project has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH): Stories of Southern Maryland. https://www.neh.gov/ Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this transcription, do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Format Interview available as MP3 file or WAV: ssoh00143 (1:34:59) Content Disclaimer The Southern Maryland Studies Center offers public access to transcripts of oral histories and other archival materials that provide historical evidence and are products of their particular times. These may contain offensive language, negative stereotypes or graphic descriptions of past events that do not represent the opinions of the College of Southern Maryland or the Southern Maryland Studies Center. Typographic Note • [Inaudible] is used when a word cannot be understood. • Brackets are used when the transcriber is not sure about a word or part of a word, to add a note indicating a non-verbal sound and to add clarifying information. • Em Dash — is used to indicate an interruption or false start. • Ellipses … is used to indicate a natural extended pause in speech Subjects African American teachers Depressions Education Education, Higher Middle school principals School integration Segregation in education Tags Depression, 1929 Music teacher Aaron C. -

A History of Money in Palestine: from the 1900S to the Present

A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mitter, Sreemati. 2014. A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12269876 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present A dissertation presented by Sreemati Mitter to The History Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2014 © 2013 – Sreemati Mitter All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Roger Owen Sreemati Mitter A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present Abstract How does the condition of statelessness, which is usually thought of as a political problem, affect the economic and monetary lives of ordinary people? This dissertation addresses this question by examining the economic behavior of a stateless people, the Palestinians, over a hundred year period, from the last decades of Ottoman rule in the early 1900s to the present. Through this historical narrative, it investigates what happened to the financial and economic assets of ordinary Palestinians when they were either rendered stateless overnight (as happened in 1948) or when they suffered a gradual loss of sovereignty and control over their economic lives (as happened between the early 1900s to the 1930s, or again between 1967 and the present). -

Aaron Hush Key Points: (Summarized from the People--Hush, Aaron File) Born in Somerville in the 1840S Married to Sarah C

Aaron Hush Key Points: (Summarized from the People--Hush, Aaron file) ● Born in Somerville in the 1840s ● Married to Sarah Catherine Roberts, with whom he had 8 children (as of 1898) ● Mustered into military service in 1864 ○ Company H 32nd Regiment U.S.C.T. Volunteer Infantry under Captain Saml. M. Smith and Col. George W. Baird ○ Participated in the Battle of Honey Hill (November 30, 1864) ■ Third battle of Sherman’s March to the Sea / the Savannah Campaign ○ Honorably discharged by reason of close of war in 1865 ● Grave rediscovered by South Brunswick resident and WW2 vet, Al Kady ● Owned property in the Sand Hills area according to granddaughter Rediscovered by South Brunswick resident and veteran Al Kady at the turn of the millennium, Aaron Hush’s grave has been recognized as an important part of the town’s history. Hush was born in Somerville sometime in the mid-1840s. He was an African American soldier who served in the 32nd Regiment of the U.S. Colored Troops throughout 1864 and 1865 in the Civil War. Hush was mustered into military service in 1864 and volunteered to serve three years. He was discharged honorably in 1865 because the war had ended. Hush was involved in the Battle of Honey Hill, also known as the third battle of Sherman’s March to the Sea, or the Savannah Campaign, which helped to disrupt the economy of the Confederacy when troops destroyed infrastructure and industry throughout the region. Additionally, in his personal life, Hush was married to Sarah Catherine Roberts, with whom he had eight children. -

Nationalism, Deprivation and Regionalism Among Arabs in Israel Author(S): Oren Yiftachel Source: Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol

The Political Geography of Ethnic Protest: Nationalism, Deprivation and Regionalism among Arabs in Israel Author(s): Oren Yiftachel Source: Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 22, No. 1 (1997), pp. 91-110 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/623053 Accessed: 19/04/2010 02:59 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Water Justice: Water As a Human Right in Israel

NO.15 ~ MARCH 2005 ~ ENGLISH VERSION Israel Water Justice: Water as a Human Right in Israel By Tamar Keinan, Friends of the Earth Middle East, Israel Editor: Gidon Bromberg, Friends of the Earth Middle East Series’ coordinator: Simone Klawitter, policy advisor Translated from Hebrew by: Ilana Goldberg Global Issue Papers, No. 15 Water Justice: Water as a Human Right in Israel: Published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, office Tel Aviv 24, Nahalat Binyamin 65162 Tel Aviv, Israel Phone: 00972-3-5167734/5 Fax: 00972-3-5167689 © Heinrich Böll Foundation 2005 All rights reserved in cooperation with EcoPeace/Friends of the Earth Middle East (FoEME) 85 Nehalat Benyamin St., Tel Aviv 66102, Israel The following paper does not necessarily represent the views of the Heinrich Böll Foundation. Note of Gratitude I would like to acknowledge the assistance and comments given by Zach Tagar and Sharon Karni staff members of the FoEME Tel-Aviv office, as well as that of a team of NGO colleagues including Shimon Tzuk, Israel Union for Environmental Defence, Nir Papay, Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel and Orit, Physicians for Human Rights in Israel, Dr. David Brooks, Friends of the Earth Canada. I would like to acknowledge special gratitude to Simone Klawitter and Julia Scherf, from the Heinrich Böll Foundation for their helpful comments, support and taking the initiative of launching this important report series. - 2 - Foreword This publication is part of a Heinrich Böll Foundation series on Water as a Human Right in the Middle East. Prior to this study on Israel, the Heinrich Böll Foundation’s Arab Middle East Office in Ramallah commissioned studies on Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon and the Palestinian Territories respectively. -

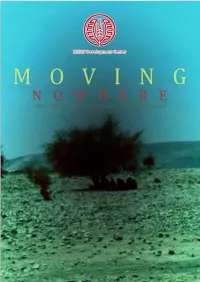

Moving-Nowhere.Pdf

MA’AN Development Center MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 1 2 MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 2015 3 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Physical Security 6 Eviction Orders And Demolition Orders 10 Psychological Security 18 Livelihood Reductions 22 Environmental Concerns 24 Water 26 Settler Violence 28 Isuues Faced By Other Communities In Area C 32 International Humanitarian Law 36 Conclusion 40 Photo by Hamza Zbiedat Hamza by Photo 4 Moving Nowhere Introduction Indirect and direct forcible transfer is currently at the forefront of Israel’s ideological agenda in area C. Firing zones, initially established as a means of land control, are now being used to create an environment so hostile that Palestinians are forced to leave the area or live in conditions of deteriorating security. re-dating the creation of the state of Israel, there was an ideological agenda within Pcertain political spheres predicated on the notion that Israel should exist from the sea to the Jordan River. Upon creation of the State the subsequent governments sought to establish this notion. This has resulted in an uncompromising programme of colonisation, ethnic cleansing and de-development in Palestine. The conclusion of the six day war in 1967 marked the beginning of the ongoing occupation, under which the full force of the ideological agenda has been extended into the West Bank. Israel has continuously led projects and policies designed to appropriate vast amounts of Palestinian land in the West Bank, despite such actions being illegal under international law. -

Trade and Commerce at Sepphoris, Israel

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects Sociology and Anthropology 1998 Trade and Commerce at Sepphoris, Israel Sarah VanSickle '98 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/socanth_honproj Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation VanSickle '98, Sarah, "Trade and Commerce at Sepphoris, Israel" (1998). Honors Projects. 19. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/socanth_honproj/19 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by Faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Trade and Commerce At Sepphoris, Israel Sarah VanSickle 1998 Honors Research Dr. Dennis E. Groh, Advisor I Introduction Trade patterns in the Near East are the subject of conflicting interpretations. Researchers debate whether Galilean cities utilized trade routes along the Sea of Galilee and the Mediterranean or were self-sufficient, with little access to trade. An analysis of material culture found at specific sites can most efficiently determine the extent of trade in the region. If commerce is extensive, a significant assemblage of foreign goods will be found; an overwhelming majority of provincial artifacts will suggest minimal trade. -

Jerusalem: City of Dreams, City of Sorrows

1 JERUSALEM: CITY OF DREAMS, CITY OF SORROWS More than ever before, urban historians tell us that global cities tend to look very much alike. For U.S. students. the“ look alike” perspective makes it more difficult to empathize with and to understand cultures and societies other than their own. The admittedly superficial similarities of global cities with U.S. ones leads to misunderstandings and confusion. The multiplicity of cybercafés, high-rise buildings, bars and discothèques, international hotels, restaurants, and boutique retailers in shopping malls and multiplex cinemas gives these global cities the appearances of familiarity. The ubiquity of schools, university campuses, signs, streetlights, and urban transportation systems can only add to an outsider’s “cultural and social blindness.” Prevailing U.S. learning goals that underscore American values of individualism, self-confidence, and material comfort are, more often than not, obstacles for any quick study or understanding of world cultures and societies by visiting U.S. student and faculty.1 Therefore, international educators need to look for and find ways in which their students are able to look beyond the veneer of the modern global city through careful program planning and learning strategies that seek to affect the students in their “reading and learning” about these fertile centers of liberal learning. As the students become acquainted with the streets, neighborhoods, and urban centers of their global city, their understanding of its ways and habits is embellished and enriched by the walls, neighborhoods, institutions, and archaeological sites that might otherwise cause them their “cultural and social blindness.” Jerusalem is more than an intriguing global historical city.