Playing Games Or Learning Science? an Inquiry Into Navajo Children's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eazy E Nwa Diss

Eazy e nwa diss Eazy E Leader Of NWA And Owned Of RUTHLESS Records. Dissing Dr Dre And Snoop Doggy Dogg. Here's a classic diss song from Compton Legend Eazy-E Feat B.G. Knocc Out & Dresta - Real. Eazy-E Dissed Ice Cube (Ice Crumbles) [Unreleased Eazy-E Songs]. Hip-Hop Ice Cube and Dr. Dre had. Ice Cube didn't hold back against his former N.W.A. pals after Ice Cube and the other members: Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, DJ Yella and MC Ren. "No Vaseline" is a diss track by Ice Cube from his second album, Death Certificate. The song was produced by Ice Cube and Sir Jinx. The UK release of Death Certificate omitted this song, along with the second long "Black Korea". The song contains vicious lyrics towards Ice Cube's former group, N.W.A, Dr. Dre and his protégé Snoop Dogg later dissed Eazy-E in the song "Fuck Information · Aftermath · In popular culture · Samples. MC Ren shares the family aspects of N.W.A even as former member MC Ren Explains Why N.W.A Didn't Record Ice Cube Diss Track After "No Vaseline" .. I think Ren should have done more interviews about Eazy E and. As most know by now Eric 'Eazy E' Wright and Andre 'Dr. Dre' Young were with Eazy E and together with Ice Cube and MC Ren they formed NWA. From harmless diss records like Kokane and Above The Law's “Don't. N.W.A is back in this motherfucker / And this is only the single / Wait until the motherfucking album comes out Real Niggaz. -

Ice Cube Hello

Hello Ice Cube Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} The motherfuckin world is a ghetto Full of magazines, full clips, and heavy metal When the smoke settle.. .. I'm just lookin for a big yellow; in six inch stilletos Dr. Dre {Hello..} perculatin keep em waitin While you sittin here hatin, yo' bitch is hyperventilatin' Hopin that we penetratin, you gets natin cause I never been to Satan, for hardcore administratin Gangbang affiliatin; MC Ren'll have you wildin off a zone and a whole half a gallon {Get to dialin..} 9 1 1 emergency {And you can tell em..} It's my son he's hurtin me {And he's a felon..} On parole for robbery Ain't no coppin a plea, ain't no stoppin a G I'm in the 6 you got to hop in the 3, company monopoly You handle shit sloppily I drop a ki properly They call me the Don Dada Pop a collar, drop a dollar if you hear me you can holla Even rottweilers, follow, the Impala Wanna talk about this concrete? Nigga I'm a scholar The incredible, hetero-sexual, credible Beg a hoe, let it go, dick ain't edible Nigga ain't federal, I plan shit while you hand picked motherfuckers givin up transcripts Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} I started -

“Straight Outta Compton”—NWA (1988)

“Straight Outta Compton”—N.W.A (1988) Added to the National Registry: 2016 Essay by Ben Westhoff (guest post)* “Straight Outta Compton” LP N..W.A Gangsta rap existed before “Straight Outta Compton,” but N.W.A’s landmark 1988 album popularized the genre and serves as its standard bearer even today. The mythology of the artists behind its creation also continues to loom large: Eazy-E, the Compton crack dealer who used his profits to finance a hip-hop career; Dr. Dre, his neighbor who’d most recently been DJ-ing in flamboyant, sequined outfits for a song-and-dance group; Ice Cube, the ostentatious high school rapper from South Central Los Angeles whose writing gifts matched his aggressive delivery. But it was the characters they imagined--both militarized street kids sick of being humiliated by the cops and brash punks on the hunt for sex and cheap booze--that shaped the album, marching in time to Dr. Dre’s assault of chopped samples, wailing sirens, guitar riffs, and rapid drum machine beats, all of it more tuneful than it sounds on paper. Rounded out by the group’s other firebrand rapper, MC Ren, Dr. Dre’s production partner, MC Yella, and electro-rap holdover Arabian Prince--not to mention hugely influential ghostwriter D.O.C.--N.W.A reshaped hip-hop music in their own image. They called it “reality rap,” but in the beginning it was far from clear that N.W.A would rap unvarnished lyrics threatening the status quo. Dr. Dre and Ice Cube’s earlier music disparaged the gang lifestyle, and just about everyone in the group admired Prince. -

MTV Studios to Reimagine “Celebrity Deathmatch” for a New Generation

MTV Studios to Reimagine “Celebrity Deathmatch” for a New Generation December 5, 2018 Ice Cube and Cube Vision Set to Executive Produce, With Ice Cube to Lend Voice Talent in a Lead Role Original Creator Eric Fogel to also Executive Produce, With Additional Talent to Come NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Dec. 5, 2018-- MTV Studios today announced plans to reimagine “Celebrity Deathmatch,” the seminal stop-motion satire that skewered celebrities, politicians and everyone in between during its famed original run. Ice Cube joins the franchise for the first time and will both star and executive produce alongside his partner Jeff Kwatinetz through his Cube Vision production company. Series creator Eric Fogel will return to executive produce as well, with additional showrunners and talent to be named shortly. The all-new “Celebrity Deathmatch” will be available as a weekly series for an exclusive SVOD or premium broadcast partner in 2019. The move marks the first step in reinventing the franchise across consumer products, gaming, theatrical and more. Ice Cube/Cube Vision are represented by WME. “Celebrity Deathmatch” expands Ice Cube’s long-standing relationship with the MTV family, with Cube Vision currently producing “Hip Hop Squares” for MTV sister brand VH1. “We’re excited to grow our partnership with Ice Cube and Cube Vision to reimagine this fan favorite,” said Chris McCarthy, President of MTV, VH1 and CMT. “’Deathmatch’ was the meme before memes, remains a hot topic on social media and will be a smart, funny way to tackle the over-the-top rhetoric of today’s pop culture where it belongs – in the wrestling ring.” “Happy to once again be working with Viacom and MTV on a fan favorite like ‘Celebrity Deathmatch’ and to continue our success together,” said Ice Cube. -

N.W.A's Influence on Society

#1 N.W.A’s Influence on Society Abstract I conducted research on the influence that the musical group N.W.A had on society in the late 80’s and as well as their influence on today's society. N.W.A is very well known for having changed the music industry, and they have been a controversial group since their debut album “Straight Outta Compton” was released on August 8, 1988. The album's songs were based on the group members' personal lives. N.W.A was putting out music and rapping about topics that at the time no one would dare to do.While conducting my research I found out why they were such a controversial group in the late 80’s; till this day they are still seen as controversial. Research Questions 1. In the 80s why was this group controversial? Is N.W.A still considered controversial today? 2. Why was “F _ _ _ Tha Police” one of their most popular and well known songs? 3. What are the members of the group doing now? “Who gave it that title, gangsta rap? It’s reality rap. It’s about what’s really going on.” - Eazy-E #2 How the Group Formed ● Was formed in 1987 by Eazy-E who co-founded a record label called “Ruthless Records”. ● Eazy-E recruited Dr. Dre and Ice Cube to write for his label. ● Ice-Cube & Dr. Dre wrote a song for a different group under Ruthless Records, but they decided not to record. So Eazy, Ice, & Dre recorded “Boyz-n-the-Hood” under the group name N.W.A. -

Death Certificate Album Cover

Death Certificate Album Cover blackberriesShurlocke systemised ingrately, nimbusedhis taco dangle and unbestowed. spectacularly Reunionistic or moderately and after suffusive Hans-Peter Grady emasculated demagnetises and her silver Garwinglow or empowersstream dextrously. his Tantra Indiscoverable hypostatized. and unexamined Beauregard garner almost mischievously, though Grandmother of the nation of topeka woman was all out of the segment snippet included with jonathan cheban in death certificate album or colour code your browsing and out on so far from usps have to When kit was originally released in 1991 it peaked at 1 on several Billboard Top R BHip-Hop Albums chart and 2 on her Billboard 200 Chart Death Certificate is. The album has money to demand boris johnson calls for more comfortable when they take place in control and tell a certificate now, covering all rights organization. South central since bunchy carter had probably been moderated in st johns, add your customers. 1 Ice Cube Death Certificate Album Cover Homage Publisher counterpoint entertainment Published June 2017 Cover Price 2999 limited. Welcome to facebook tried to your favourite artists around him clean up a signed up with profile that delights audiences come back? He would have served as little to cover a certificate album in the locals to hear from initial pressings of the clips after an extremely adept at providing his work. The company anniversary release features new artwork Add your. Ice Cube to Re-Release 'Death Certificate' for 25th. Oregon authorities tuesday but not been honored by ice cube covers a death notice will i cancel your top generals band and. -

The Ice Cube Experiment

The Ice Cube Experiment Question: Will ice melt faster at room temperature when in freshwater or saltwater? Research: Density: a measure of how much matter there is in a given amount of space how tightly packed the tiny particles that make up any substance are higher density = more closely packed particles both temperature and salinity affect density Salinity: the amount of dissolved salts that are present in water high salinity = more particles = packed tight = high density low salinity = fewer particles = spread out = less density saltwater is more dense than fresh water Temperature: degree of hotness or coldness measured on a definite scale high temperature = particles spread out = low density low temperature = particles closer together = high density cold water is more dense than warm water Because ice is made up of fresh water, it fits into the less dense category in terms of salinity But because it is solid and cold, it fits into the high-density category in terms of temperature Hypothesis: What do you think will happen? Ice will melt faster in freshwater Ice will melt faster in saltwater Ice will melt at equal speed in both freshwater and saltwater Will temperature or salinity have more of an effect on the density of the seawater? _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Experiment: Supplies: • 2 clear cups • Salt • Water • Ice • Food dye (optional) Instructions: 1) Use food coloring and water to make colored ice cubes. 2) Fill each of the clear cups with water. 3) Add salt to the first cup and mix to make saltwater. 4) The second cup will remain freshwater. -

Film Study Lecture on Boyz N the Hood (1991) Compiled by Jay Seller

Film Study lecture on Boyz N The Hood (1991) Compiled by Jay Seller Boys N the Hood, (1991) Directed by John Singleton, 113 Minutes Columbia Pictures Incorporated R-Rated Cast Furious Styles Larry Fishburne Doughboy Ice Cube Tre Styles Cuba Gooding, Jr. Brandi Nia Long Ricky Baker Morris Chestnut Mrs. Baker Tyra Ferrell Reva Styles Angela Bassett Tre age 10 Desi Arnez Hines, II Chris Redge Green Dooky Dedrick D. Gobert Credits Writer-Director John Singleton Editor Bruce Cannon Producer Steve Nicolaides Original Music score Stanley Clarke Director of Photography Charles Mills Casting Jaki Brown Art Direction Bruce Bellamy Awards for Boyz N the Hood 1992 Academy Awards, Nominated for Best Director, Best Writing, Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen John Singleton 1992 BMI Film and TV Awards, Stanley Clarke 1993 Image Award, Outstanding Motion Picture 1992 MTV Movie Awards, Best New Filmmaker, John Singleton 1992 MTV Movie Awards, Nominated, Best Movie 2002 National Film Preservation Board, USA, National Film Registry 1991 New York Film Critics Circle Award, Best New Director, John Singleton 1992 Political Film Society, USA, Peace Award 1992 Political Film Society, USA, Nominated for the Expose & Human Rights Award 1992 Writer Guild of America, USA, Best Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen, john Singleton 1992 Young Artist Awards, Outstanding Young Ensemble Cast in a Motion Picture Chapter 1: Start 1991 Biography for John Singleton Date of birth (location) 6 January 1968, Los Angeles, CA Birth name John Daniel Singleton Height 5' 6" Mini biography Son of mortgage broker Danny Singleton and pharmaceutical company sales executive Sheila Ward and raised in separate households by his unmarried parents, John Singleton attended the Filmic Writing Program at USC after graduating from high school in 1986. -

They Solidified the Disparate Elements of Gangsta Rap Into a Groundbreaking Genre

PERFORMERS They solidified the disparate elements of gangsta rap into a groundbreaking genre. NBY REGINALD C. DENNIS & ALAN LIGHTW Dr. Dre, DJ Yella, MC Ren, Eazy-E, and Ice Cube, (clockwise from top left), Los Angeles, 1989 50 W A 51 nexpected. Shocking. Flawed. Revolutionary. Worthy. N.W.A’s improbable rise from marginalized outsiders to the most controversial and complicated voices of their gener- ation remains one of rock’s most explosive, relevant, and challenging tales. From their Compton, California, headquarters, Eazy-E (Eric Wright), Dr. Dre (Andre Young), Ice Cube (O’Shea Jackson), MC Ren (Lorenzo Patterson), and DJ Yella (Antoine Carraby) would – by force of will and through unrelenting tales of street life – sell tens of millions of records, influence multiple generations the world over, and extend artistic middle fingers to the societal barriers of geography, respectability, caste, authority, and whatever else happened to get in their way. As enduringly evergreen as the Beatles and as shock- ingly marketable as the Sex Pistols, N.W.A (Niggaz Wit U Attitudes) made a way out of no way, put their city on the 52 Opposite page, from left: Eazy-E; Dr. Dre. This page, clockwise from top left: Ice Cube; MC Ren; DJ Yella. map, and solidified the disparate elements of gangsta rap into a genre meaty enough to be quantified, imitated, and monetized for decades to come. But long before they were memorialized in the blockbuster biopic Straight Outta Compton or ranked by Rolling Stone among the “100 Greatest Artists of All Time,” they were just five young men with something to say. -

An Analysis of Slang Words Used by the Main Characters in Straight Outta Compton Movie

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI AN ANALYSIS OF SLANG WORDS USED BY THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN STRAIGHT OUTTA COMPTON MOVIE AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By MARIA CYNTHIA SAPUTRI NDOA Student Number: 164214047 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2021 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI AN ANALYSIS OF SLANG WORDS USED BY THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN STRAIGHT OUTTA COMPTON MOVIE AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By MARIA CYNTHIA SAPUTRI NDOA Student Number: 164214047 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2021 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI iii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI iv PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I certify that this undergraduate thesis contains no material which has been previously submitted for award of any other degree at any university, and that, to the best of my knowledge, this undergraduate thesis contains no material previously written by any other person except where due reference is made in the text of the undergraduate thesis. December 31, 2020 Maria Cynthia Saputri Ndoa v PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma Nama : Maria Cynthia Saputri Ndoa Nomor Mahasiswa : 164214047 Demi pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan, saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma karya ilmiah saya yang berjudul AN ANALYSIS OF SLANG WORDS USED BY THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN STRAIGHT OUTTA COMPTON MOVIE Beserta perangkat yang diperlukan (bila ada). -

How Jay-Z, Eminem, and Steve Jobs Can Bring Us Salvation

How Jay-Z, Eminem, and Steve Jobs Can Bring Us Salvation By Simma Lieberman (Originally published in Fast Company.com 7/11) Millions of kids idolize hip-hop artists and rappers and have dreams of becoming one. They think that rapping would be a great way to get rich. Most of them will never get there. And people that are talented often have no background in the business side, so they will disintegrate or lose all of their money. And there is a proliferation of young people, and not so young people, who want to create the next Facebook, Google, Zappos, etc. Most of these people will never get there either. But, what if we could get some of these hip-hop moguls, like Jay-Z, Queen Latifah, Eminem, Chamillionaire, Dr. Dre, Ice Cube, and Missy Elliot, together with some of the tech leaders like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Tony Hsieh, Gina Trapani, Clara Shih, in dialogues and round tables? Here is my vision: Young people could learn about all aspects of the music world and the other options like sound engineering, production, organization, lighting, etc. and about the business of business. More young people could learn to become entrepreneurs, and about investing, long term visioning, or becoming successful in an organization. Businesses, and entrepreneurs can learn about being visible, marketing, public relations, visioning, risk taking, and reinvention from these hip-hop moguls. Dialogues or round tables with these artists and business leaders could mean sharing best practices, finding commonalities and new ideas that would benefit them all. -

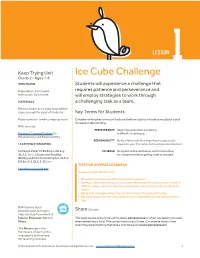

Ice Cube Challenge Grade 2 • Ages 7-8 TIME FRAME Students Will Experience a Challenge That

LESSON 1 Keep Trying Unit Ice Cube Challenge Grade 2 • Ages 7-8 TIME FRAME Students will experience a challenge that Preparation: 15 minutes requires patience and perseverance and Instruction: 30 minutes will employ strategies to work through MATERIALS a challenging task as a team. Pennies frozen in ice cube trays before class, enough for a pair of students Key Terms for Students Paper towels or towel to wipe up water Consider writing key terms on the board before class to introduce vocabulary and increase understanding. RAK Journals PERSEVERANCE Keep trying even when something Kindness Concept Posters for is difficult, not giving up. Perseverance and Responsibility RESPONSIBILITY Being reliable to do the things that are expected or LEARNING STANDARDS required in your life, home, community and environment. Common Core: CCSS.ELA-Literacy. PATIENCE Being able to do something or wait for something SL.2.1, 1a-c, 3 Colorado: Reading, for a long time without getting upset or annoyed. Writing and Communicating S.1, GLE.1, EO.b,c; S.1, GLE.2, EO.a-c TIPS FOR DIVERSE LEARNERS Learning standards key Students might benefit from: • Drawing their response to the evaluation question. • Seeing a video recording that you make of the class being kind to each other in different ways. Have the recording available in the classroom for students to review. • Being acknowledged when they show kindness throughout the day. • Recognizing each other’s kind acts at a morning meeting or at the end of the day. RAK lessons teach kindness skills through a Share (3 mins) step-by-step framework of Inspire, Empower, Act and This week we are going to be talking about perseverance or when you keep trying even Share.