Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF(All Devices)

Published by: The Irish Times Limited (Irish Times Books) © The Irish Times 2014. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of The Irish Times Limited, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographic rights organisation or as expressly permitted by law. Contents Watching from a window as we all stay the same ................................................................ 4 Emigration- an Irish guarantor of continuity ........................................................................ 7 Completing a transaction called Ireland ................................................................................ 9 In the land of wink and nod ................................................................................................. 13 Rhetoric, reality and the proper Charlie .............................................................................. 16 The rise to becoming a beggar on horseback ...................................................................... 19 The real spiritual home of Fianna Fáil ................................................................................ 21 Electorate gives ethics the cold shoulders ........................................................................... 24 Corruption well known – and nothing was done ................................................................ 26 Questions the IRA is happy to ignore ................................................................................ -

The Government's Executions Policy During the Irish Civil

THE GOVERNMENT’S EXECUTIONS POLICY DURING THE IRISH CIVIL WAR 1922 – 1923 by Breen Timothy Murphy, B.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisor of Research: Dr. Ian Speller October 2010 i DEDICATION To my Grandparents, John and Teresa Blake. ii CONTENTS Page No. Title page i Dedication ii Contents iii Acknowledgements iv List of Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The ‗greatest calamity that could befall a country‘ 23 Chapter 2: Emergency Powers: The 1922 Public Safety Resolution 62 Chapter 3: A ‗Damned Englishman‘: The execution of Erskine Childers 95 Chapter 4: ‗Terror Meets Terror‘: Assassination and Executions 126 Chapter 5: ‗executions in every County‘: The decentralisation of public safety 163 Chapter 6: ‗The serious situation which the Executions have created‘ 202 Chapter 7: ‗Extraordinary Graveyard Scenes‘: The 1924 reinterments 244 Conclusion 278 Appendices 299 Bibliography 323 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my most sincere thanks to many people who provided much needed encouragement during the writing of this thesis, and to those who helped me in my research and in the preparation of this study. In particular, I am indebted to my supervisor Dr. Ian Speller who guided me and made many welcome suggestions which led to a better presentation and a more disciplined approach. I would also like to offer my appreciation to Professor R. V. Comerford, former Head of the History Department at NUI Maynooth, for providing essential advice and direction. Furthermore, I would like to thank Professor Colm Lennon, Professor Jacqueline Hill and Professor Marian Lyons, Head of the History Department at NUI Maynooth, for offering their time and help. -

A Short History of the War of Independence

Unit 6: The War of Independence 1919-1921 A Short History Resources for Secondary Schools UNIT 7: THE IRISH WAR OF INDEPENDENCE PHASE I: JAN 1919 - MARCH 1920 police boycott The first phase of the War of Independence consisted Eamon de Valera escaped from Lincoln Jail on 3 mainly of isolated incidents between the IRA and the February 1919 and when the remaining ‘German Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). From the beginning Plot’ prisoners were released in March 1919, the of the conflict, the British government refused to President of the Dáil was able to return to Ireland recognise the Irish Republic or to admit that a state without danger of arrest. He presided at a meeting of of war existed between this republic and the UK. The Dáil Éireann on 10 April 1919 at which the assembly violence in Ireland was described as ‘disorder’ and the confirmed a policy of boycotting against the RIC. IRA was a ‘murder gang’ of terrorists and assassins. For this reason, it was the job of the police rather than The RIC are “spies in our midst … the eyes and the 50,000-strong British army garrison in Ireland ears of the enemy ... They must be shown and to deal with the challenge to the authority of the made to feel how base are the functions they British administration. British soldiers would later perform and how vile is the position they become heavily involved in the conflict, but from the occupy”. beginning the police force was at the front line of the - Eamon de Valera (Dáil Debates, vol. -

Defence Forces Review 2016

Defence Forces Review Defence Forces 2016 Defence Forces Review 2016 Pantone 1545c Pantone 125c Pantone 120c Pantone 468c DF_Special_Brown Pantone 1545c Pantone 2965c Pantone Pantone 5743c Cool Grey 11c Vol 13 Vol Printed by the Defence Forces Printing Press Jn14102 / Sep 2016/ 2300 Defence Forces Review 2016 ISSN 1649 - 7066 Published for the Military Authorities by the Public Relations Branch at the Chief of Staff’s Division, and printed at the Defence Forces Printing Press, Infirmary Road, Dublin 7. © Copyright in accordance with Section 56 of the Copyright Act, 1963, Section 7 of the University of Limerick Act, 1989 and Section 6 of the Dublin University Act, 1989. The material contained in these articles are the views of the authors and do not purport to represent the official views of the Defence Forces. DEFENCE FORCES REVIEW 2016 PREFACE “By academic freedom I understand the right to search for truth and to publish and teach what one holds to be true. This right implies also a duty: one must not conceal any part of what one has recognized to be true. It is evident that any restriction on academic freedom acts in such a way as to hamper the dissemination of knowledge among the people and thereby impedes national judgment and action”. Albert Einstein As Officer in Charge of Defence Forces Public Relations Branch, it gives me great pleasure to be involved in the publication of the Defence Forces Review for 2016. This year’s ‘Review’ continues the tradition of past editions in providing a focus for intellectual debate within the wider Defence Community on matters of professional interest. -

The Anglo-Irish Truce of 11 July 1921 Which Brought a Formal Conclusion to the Irish War of Independence

University of Limerick Ollscoil Luimnigh The Anglo - Irish Truce: An analysis of its immediate military impact, 8 - 11 July 1921 Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc Ph.D. 2014 University of Limerick Ollscoil Luimnigh The Anglo - Irish Truce: An analysis of its immediate military impact, 8 - 11 July 1921 Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc Thesis presented to the University of Limerick for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Dr. Ruán O’Donnell Submitted to the University of Limerick, September 2014 Abstract This thesis is a study of the dynamics of the Anglo-Irish Truce of 11 July 1921 which brought a formal conclusion to the Irish War of Independence. Although this work explores the origins, character and significance of the agreement, its primary focus is an analysis of the effect the announcement the impending armistice had on the use of lethal violence in the final days and hours of the conflict. It uses empirical data to interrogate existing hypotheses, and test popular theories surrounding the cessation of the Irish Republican Army’s military campaign. Furthermore, it examines in detail the hitherto neglected subject of the reaction and responses of the British forces in Ireland to the agreement. This study also establishes the role the advent of the Truce played in fomenting ‘Belfast’s Bloody Sunday’, one of the most intense outbreaks of sectarian violence in modern Irish history. This thesis addresses key questions which are central to understanding the Truce and the conflict as a whole. The new research presented in this study challenges an established historical narrative. The empirical findings make a useful contribution to the development of a more complex and comprehensive history of the Irish revolutionary period. -

The Irish Civil War, 1922-1923: a Military Study of the Conventional Phase, 28 June - 11 August, 1922

A paper delivered to NYMAS Paul V. Walsh at the CUNY Graduate Center, 3412 Huey Ave New York, N.Y. Drexel Hill, PA. 19026-2311 on 11 December 1998. [email protected] THE IRISH CIVIL WAR, 1922-1923: A MILITARY STUDY OF THE CONVENTIONAL PHASE, 28 JUNE - 11 AUGUST, 1922. The Irish Civil War was one of the many conflicts that followed in the wake of the First World War. By the standards of the 'Great War' it was very small indeed; roughly 3,000 deaths were inflicted over a period of eleven months, probably less than the average casualties suffered on the Western Front during a quiet week. (1) However, wars should not be judged solely by the 'Butcher's Bill'. The Civil War contributed directly to the character of Ireland and Anglo-Irish relations, creating patterns that have only begun to be challenged in the past thirty years. As with all civil wars, this conflict generated extremes of bitterness that have haunted public and political life in Ireland up to the present day. Indeed, it is only after the passage of seventy-five years that scholars are able to approach the subject of the Civil War with some degree of detachment. Significantly the two main political parties in Ireland, Fianna Fail and Fine Gael, are the direct descendants of the opposing sides of the war. Although partition was an established fact at the beginning of the war, the conflict in the South only served to further undermine any possibility of reunification. Thus the Civil War is one of the factors that has contributed to the thirty years of conflict in Northern Ireland which only now may be in the process of being resolved. -

INDEX Compiled by W Stephen Gilbert Page References in Italics Indicate Illustrations

INDEX Compiled by W Stephen Gilbert page references in italics indicate illustrations A Byrne, Vinnie 71, 73–9, 123, 143, 165–7, Anderson, Sir John 129, 202, 219–20 217, 220–1, 235, 269, 300 Andrews, Todd: quoted 218 quoted 8–9, 38, 74, 76, 77, 79, 80–1, Anglo-Irish pre-20th century history 17 123, 127, 131, 166, 167–8, 235 Anglo-Irish War 13, 67–241, 257, 271, ‘sharp shooter’ 79 286 Byrnes, John Charles (aka Jameson) 136– and intelligence 11–12, 86–7 7, 138–9 Treaty of 1921 148, 242–53, 288 quoted 137 Asquith, Herbert 19–20, 54 C B Cahill, Head Constable Patrick 156 Balfour, Arthur 58, 239–40 Caldwell, Paddy 75 Barrett, Ben 75 Carolan, Professor John 199, 201 Barry, Kevin 203–7, 210 Carson, Edward 22–6, 54, 58, 89, 147 Barry, Tom 223, 259 Casement, Roger 30, 32, 37, 68, 132 Barry family 204–5 Catholics 17–18, 19, 21, 24, 35, 39, 59, Barton, John ‘Johnny’ 123–6 72–3, 106, 109, 150, 159–60, 203, Batchelor, William 120–1 239, 257, 261, 266, 289, 291 Béaslaí, Piaras 70, 74, 110–11 Childers, Erskine 247, 249, 252–3, 262, quoted 99–100 265–6 Bell, Alan 116–17, 133–6, 137 Churchill, Randolph 18–19, 20–1, 179 Boland, Harry 60, 62–3, 111, 250 Churchill, Winston 11, 179, 253 Bonar Law, Andrew 21, 58, 89, 95 Civil War 72–3, 105, 121, 244, 251–2, Breen, Dan 61–2, 72–3, 74, 76, 81, 142– 257–86, 287–92, 294 3, 199–202, 259 endgame 262, 266, 268, 285–7, 291–2 quoted 73, 77, 202 . -

Centenary Timeline for the County of Cork (1920 – 1923)

CENTENARY TIMELINE FOR THE COUNTY OF CORK (1920 – 1923) – WAR OF INDEPENDENCE AND CIVIL WAR Guidance Note: This document provides hundreds of key dates with regard to the involvement of County Cork in the War of Independence and Civil War. These include the majority of the key occurrences of 1920 – 1923 including all major events from the County of Cork (including some other locations that involved people from County Cork), as well as key developments on the national level (or elsewhere in the country) during this timeframe (blue). All key ambushes, attacks and executions are included as well as events that saw the loss of life of Cork people, whether in Cork County or further afield. A number of notable events pertaining to Cork City (note: not all) are also included (green) and a details/link section is provided to indicate the source material. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information contained within this document, given the volume of material and variations in the historical record, there will undoubtedly be errors, omissions and other such issues. It is the intention of Cork County Council’s Commemorations Committee that this will remain a ‘live document’ and all suggested additional dates/amendments/etc. are most welcome, with this document being continually updated as appropriate. Cork County Council’s Commemorations Committee recognises and wishes to pay tribute to the excellent research already undertaken by some excellent scholars regarding this time period and looks forward to further correspondence from community groups and other interested persons. It is the purpose of this document to provide such dates that will assist local community groups in the organising of their local centenary events. -

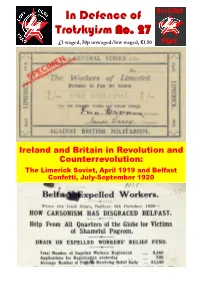

In Defence of Trotskyism No. 27 £1 Waged, 50P Unwaged/Low Waged, €1.50

In Defence of Trotskyism No. 27 £1 waged, 50p unwaged/low waged, €1.50 2 to ‘No Platform’ fascists but we never call on the Socialist Fight Where We capitalist state to ban fascist marches or parties; these laws would inevitably primarily be used against work- Stand (extracts) ers’ organisations, as history has shown. 1. We stand with Karl Marx: ‘The emancipation of the 14. We oppose all immigration controls. International working classes must be conquered by the working finance capital roams the planet in search of profit and classes themselves. The struggle for the emancipation imperialist governments disrupts the lives of workers of the working class means not a struggle for class and cause the collapse of whole nations with their privileges and monopolies but for equal rights and direct intervention in the Balkans, Iraq and Afghani- duties and the abolition of all class rule’ (The Interna- stan and their proxy wars in Somalia and the Demo- tional Workingmen’s Association 1864, General cratic Republic of the Congo, etc. Workers have the Rules). The working class ‘cannot emancipate itself right to sell their labour internationally wherever they without emancipating itself from all other sphere of get the best price. society and thereby emancipating all other spheres of 19. As socialists living in Britain we take our responsi- society’ (Marx, A Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s bilities to support the struggle against British imperial- Philosophy of Right, 1843). ism’s occupation of the six north-eastern counties of 9. We are completely opposed to man-made climate Ireland very seriously. -

Irish Political Review, September 2006

To Be Or Not IRB?/2 Captain Kelly The Volunteer Manus O'Riordan Harry Boland Labour Comment page 12 page 7 back page IRISH POLITICAL REVIEW September 2006 Vol.21, No.9 ISSN 0790-7672 and Northern Star incorporating Workers' Weekly Vol.20 No.9 ISSN 954-5891 Protestant Alienation Rogue Democracies Garret FitzGerald told the John Hewitt Summer School that "the dichotomy between The implied position behind the Gael. and Planter reflects a cultural myth rather than a genetic reality" (Irish News 25 Ameranglian invasion and destruction of Aug). the Iraqi State (and Irish support of it), and That's what we were told back in 1969 when we suggested that the Ulster Protestant the Israeli invasion and attempted community should be negotiated with as a distinct nationality. We recall that Official destruction of the Lebanese State, is that Sinn Fein leader, Tomás Mac Giolla, was particularly eloquent on the subject: there was states which present themselves as no racial difference, therefore the differences which appeared to exist were unreal and democracies have the right to impose their might be conjured away. will on states which they assert are not Is there such a thing as "a genetic reality" in political affairs? We thought the idea democratic. In other words, it is their that there was had died with Hitler—until we came across the fact that, ten years after position that states which are not demo- the death of Hitler, Hubert Butler, a Protestant gentleman of Kilkenny, had contested a cratic have no right to existence. local election on a programme which asserted the social and political superiority of It goes even farther in the case of "Protestant blood". -

200 Years of Griffith College

Griffith College Dublin A history of the campus 1813-2013 Griffith College Dublin A history of the campus 1813-2013 by John Dorney with contributions from Pat McCarthy and Matthew Foyle Published by Griffith College Dublin, South Circular Road, Dublin 8, Ireland www.gcd.ie Copyright © Griffith College Dublin 2013 ISBN 9781906878078 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing of the publisher. Map on page 8: © Ordnance Survey Ireland/Government of Ireland Copyright Permit No. MP 0009913 Design & layout by Martin Keaney www.keaneydesign.ie Printed by Brunswick Press Ltd, Dublin Contents Introduction by Prof. Diarmuid Hegarty 5 Chapter 1 – The Richmond Bridewell 1813-1892 7 Chapter 2 – Wellington Barracks 1892-1922 25 Chapter 3 – Griffith Barracks in the Irish Civil War 1922-23 39 Chapter 4 – Griffith Barracks 1923-1991 55 Chapter 5 – Arthur Griffith 65 Chapter 6 – From Barracks to College 71 Bibliography 90 3 4 Introduction s President of Griffith College it is my honour to welcome you to this book which commemorates A the 200th anniversary of the historic buildings on the Griffith College Dublin campus. As this book outlines, the campus has a varied history. The area was originally known as Grimswood’s Nurseries. In 1813 construction began on a remand prison, subsequently known as the Richmond Bridewell, designed to relieve pressure on Newgate Prison. The prison went on to house famous Irish patriots including Daniel O’Connell, James Stephens, Tom Steele and Thomas Francis Meagher. -

The Naval Forces of the Irish State, 1922- 1977

The Naval Forces of the Irish State, 1922- 1977. by Padhraic Ó Confhaola THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Supervisor of Research: Dr. Ian Speller Month and Year of Submission: October 2009 Table of Contents Acknowledgements i Abbreviations ii Introduction iii 1. The Civil War 1 2. Between the Wars 31 3. The Emergency 50 4. The Foundation of the Service 81 5. A False Dawn 99 6. The Decline of the Service 114 7. EEC Accession and the Revival of the Service 128 8. Conclusions 141 Bibliography 148 Acknowledgements My deepest thanks to my parents, Seamus and Máire, and my sisters, Máire-Aine and Kate. Their unfailing support and encouragement has been greatly appreciated. Grá agus Buíochas. My sincerest thanks must go to my supervisor, Dr. Ian Speller, for his assistance in this most trying of tasks and providing me with ample opportunities to speak on this topic to the unwitting victims of the Naval Cadet courses at NUI, Maynooth. I would also extend my gratitude to Professor R.V. Comerford and the Department of Modern History for granting me the opportunity to undertake this project. My appreciation goes to Commandant Victor Laing and the staff of the Irish Military Archives who went to some trouble in allowing me access to the files of the Naval Service and permitting me to reproduce images from their collections within this work. The staff of the Irish National Archives and their counter-parts in the British National Archives deserve mention for their efforts to aid me in trawling through their repositories.