This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

Schubert's!Voice!In!The!Symphonies!

! ! ! ! A!Search!for!Schubert’s!Voice!in!the!Symphonies! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Camille!Anne!Ramos9Klee! ! Submitted!to!the!Department!of!Music!of!Amherst!College!in!partial!fulfillment! of!the!requirements!for!the!degree!of!Bachelor!of!Arts!with!honors! ! Faculty!Advisor:!Klara!Moricz! April!16,!2012! ! ! ! ! ! In!Memory!of!Walter!“Doc”!Daniel!Marino!(191291999),! for!sharing!your!love!of!music!with!me!in!my!early!years!and!always!treating!me!like! one!of!your!own!grandchildren! ! ! ! ! ! ! Table!of!Contents! ! ! Introduction! Schubert,!Beethoven,!and!the!World!of!the!Sonata!! 2! ! ! ! Chapter!One! Student!Works! 10! ! ! ! Chapter!Two! The!Transitional!Symphonies! 37! ! ! ! Chapter!Three! Mature!Works! 63! ! ! ! Bibliography! 87! ! ! Acknowledgements! ! ! First!and!foremost!I!would!like!to!eXpress!my!immense!gratitude!to!my!advisor,! Klara!Moricz.!This!thesis!would!not!have!been!possible!without!your!patience!and! careful!guidance.!Your!support!has!allowed!me!to!become!a!better!writer,!and!I!am! forever!grateful.! To!the!professors!and!instructors!I!have!studied!with!during!my!years!at! Amherst:!Alison!Hale,!Graham!Hunt,!Jenny!Kallick,!Karen!Rosenak,!David!Schneider,! Mark!Swanson,!and!Eric!Wubbels.!The!lessons!I!have!learned!from!all!of!you!have! helped!shape!this!thesis.!Thank!you!for!giving!me!a!thorough!music!education!in!my! four!years!here!at!Amherst.! To!the!rest!of!the!Music!Department:!Thank!you!for!creating!a!warm,!open! environment!in!which!I!have!grown!as!both!a!student!and!musician.!! To!the!staff!of!the!Music!Library!at!the!University!of!Minnesota:!Thank!you!for! -

La Société Philharmonique

The Historic New Orleans Collection & Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra Carlos Miguel Prieto Adelaide Wisdom Benjamin Music Director and Principal Conductor Pr eseNT Identity, History, Legacy La Société PhiLh ar monique Thomas Wilkins, conductor Walter Harris Jr., speaker Kisma Jordan, soprano Joseph Meyer, violin Jean-Baptiste Monnot, organ/piano Phumzile Sojola, tenor THursday, February 10, 2011 Cathedral-basilica of st. Louis, King of France New Orleans, Louisiana Fr Iday, February 11, 2011 slidell High school slidell, Louisiana The Historic New Orleans Collection and the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra gratefully acknowledge rev. Msgr. Crosby W. Kern and the staff of the st. Louis Cathedral for their generous support and assistance. The musical culture of New Orleans’s free people of color and their descendants is one of the most extraordinary aspects of Louisiana history, and it is part of a larger, shared legacy. Only within the context of the development of african music in the New World can the contributions of these sons and daughters of Louisiana be fully appreciated. The first africans arrived in the New World with the initial wave of spanish colonization in the early sixteenth century. Interactions among european, african, and indigenous populations yielded new forms of cultural expression—although african music in the New World remained strongly dependent on wind instruments (such as ivory trumpets), drums, and call-and-response patterns. as early as 1572, africans were gathering in front of the famous aztec calendar stone in Mexico City on sunday afternoons to dance and sing. When Viceroy antonio de Mendoza triumphantly entered Lima on august 31, 1551, his procession’s route was lined with african drummers. -

Wagner and Bayreuth Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Brahms and Detmold

MUSIC DOCUMENTARY 30 MIN. VERSIONS Wagner and Bayreuth Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) No city in the world is so closely identified with a composer as Bayreuth is with Richard Wag- ner. Towards the end of the 19th century Richard Wagner had a Festival Theatre built here and RIGHTS revived the Ancient Greek idea of annual festivals. Nowadays, these festivals are attended by Worldwide, VOD, Mobile around 60,000 people. ORDER NUMBER 66 3238 VERSIONS Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Felix Mendelssohn, one of the most important composers of the 19th century, was influenced decisively by Berlin, which gave shape to the form and development of his music. The televi- RIGHTS sion documentary traces Mendelssohn’s life in the Berlin of the 19th century, as well as show- Worldwide, VOD, Mobile ing the city today. ORDER NUMBER 66 3305 VERSIONS Brahms and Detmold Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Around the middle of the 19th century Detmold, a small town in the west of Germany, was a centre of the sort of cultural activity that would normally be expected only of a large city. An RIGHTS artistically-minded local prince saw to it that famous artists came to Detmold and performed in Worldwide, VOD, Mobile the theatre or at his court. For several years the town was the home of composer Johannes Brahms. Here, as Court Musician, he composed some of his most beautiful vocal and instru- ORDER NUMBER ment works. 66 3237 dw-transtel.com Classics | DW Transtel. -

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

Franco-Belgian Violin School: on the Rela- Tionship Between Violin Pedagogy and Compositional Practice Convegno Festival Paganiniano Di Carro 2012

5 il convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Convegno Società dei Concerti onlus 6 La Spezia Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini Lucca in collaborazione con Palazzetto Bru Zane Centre de Musique Romantique Française Venezia Musicalword.it CAMeC Centro Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Piazza Cesare Battisti 1 Comitato scientifico: Andrea Barizza, La Spezia Alexandre Dratwicki, Venezia Lorenzo Frassà, Lucca Roberto Illiano, Lucca / La Spezia Fulvia Morabito, Lucca Renato Ricco, Salerno Massimiliano Sala, Pistoia Renata Suchowiejko, Cracovia Convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Programma Lunedì 9 LUGLIO 10.00-10.30: Registrazione e accoglienza 10.30-11.00: Apertura dei lavori • Roberto Illiano (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini / Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Francesco Masinelli (Presidente Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Massimiliano Sala (Presidente Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) • Étienne Jardin (Coordinatore scientifico Palazzetto Bru Zane, Venezia) • Cinzia Aloisini (Presidente Istituzione Servizi Culturali, Comune della Spezia) • Paola Sisti (Assessore alla Cultura, Provincia della Spezia) 10.30-11.30 Session 1 Nicolò Paganini e la scuola franco-belga presiede: Roberto Illiano 7 • Renato Ricco (Salerno): Virtuosismo e rivoluzione: Alexandre Boucher • Rohan H. Stewart-MacDonald (Leominster, UK): Approaches to the Orchestra in Paganini’s Violin Concertos • Danilo Prefumo (Milano): L’infuenza dei Concerti di Viotti, Rode e Kreutzer sui Con- certi per violino e orchestra di Nicolò Paganini -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Concert Program

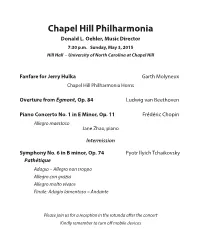

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

The German Romantic Movement

The German Romantic Movement Start date 27 March 2020 End date 29 March 2020 Venue Madingley Hall Madingley Cambridge CB23 8AQ Tutor Dr Robert Letellier Course code 1920NRX040 Director of ISP and LL Sarah Ormrod For further information on this Zara Kuckelhaus, Fleur Kerrecoe course, please contact the Lifelong [email protected] or 01223 764637 Learning team To book See: www.ice.cam.ac.uk or telephone 01223 746262 Tutor biography Robert Ignatius Letellier is a lecturer and author and has presented some 30 courses in music, literature and cultural history at ICE since 2002. Educated in Grahamstown, Salzburg, Rome and Jerusalem, he is a member of Trinity College (Cambridge), the Meyerbeer Institute Schloss Thurmau (University of Bayreuth), the Salzburg Centre for Research in the Early English Novel (University of Salzburg) and the Maryvale Institute (Birmingham) as well as a panel tutor at ICE. Robert's publications number over 100 items, including books and articles on the late seventeenth-, eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century novel (particularly the Gothic Novel and Sir Walter Scott), the Bible, and European culture. He has specialized in the Romantic opera, especially the work of Giacomo Meyerbeer (a four-volume English edition of his diaries, critical studies, and two analyses of the operas), the opera-comique and Daniel-François-Esprit Auber, Operetta, the Romantic Ballet and Ludwig Minkus. He has also worked with the BBC, the Royal Opera House, Naxos International and Marston Records, in the researching and preparation of productions. University of Cambridge Institute of Continuing Education, Madingley Hall, Cambridge, CB23 8AQ www.ice.cam.ac.uk Course programme Friday Please plan to arrive between 16:30 and 18:30. -

Ludwig Van Beethoven Franz Schubert Wolfgang

STIFTUNG MOZARTEUM SALZBURG WEEK LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN PIANO CONCERTO NO. 1 FRANZ SCHUBERT SYMPHONY NO. 5 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART PIANO CONCERTO NO. 23 ANDRÁS SCHIFF CAPPELLA ANDREA BARCA WEEK LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Vienna - once the music hub of Europe - attracted all the Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15 greatest composers of its day, among them Beethoven, Schubert and Mozart. This concert given by András Schiff and FRANZ SCHUBERT the Capella Andrea Barca during the Salzburg Mozart Week Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, D 485 brings together three works by these great composers, which WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART each of them created early in life at the start of an impressive Piano Concerto No. 23 in E flat major, KV 482 Viennese career. The programme opens with Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto: Piano & Conductor András Schiff “Sensitively supported by the rich and supple tone of the strings, Orchestra Cappella Andrea Barca Schiff’s pianistic virtuosity explores the length and breadth of Beethoven’s early work, from the opulent to the playful, with a Produced by idagio.production palpable delight rarely found in such measure in a pianist”, was Video Director Oliver Becker the admiring verdict of the Salzburg press. Length: approx. 100' As in his opening piece, Schiff again succeeded in Schubert’s Shot in HDTV 1080/50i symphony “from the first note to the last in creating a sound Cat. no. A 045 50045 0000 world that flooded the mind’s eye with images” Drehpunkt( Kultur). A co-production of The climax of the concert was the Mozart piano concerto. -

Gardiner's Schumann

Sunday 11 March 2018 7–9pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT GARDINER’S SCHUMANN Schumann Overture: Genoveva Berlioz Les nuits d’été Interval Schumann Symphony No 2 SCHUMANN Sir John Eliot Gardiner conductor Ann Hallenberg mezzo-soprano Recommended by Classic FM Streamed live on YouTube and medici.tv Welcome LSO News On Our Blog This evening we hear Schumann’s works THANK YOU TO THE LSO GUARDIANS WATCH: alongside a set of orchestral songs by another WHY IS THE ORCHESTRA STANDING? quintessentially Romantic composer – Berlioz. Tonight we welcome the LSO Guardians, and It is a great pleasure to welcome soloist extend our sincere thanks to them for their This evening’s performance of Schumann’s Ann Hallenberg, who makes her debut with commitment to the Orchestra. LSO Guardians Second Symphony will be performed with the Orchestra this evening in Les nuits d’été. are those who have pledged to remember the members of the Orchestra standing up. LSO in their Will. In making this meaningful Watch as Sir John Eliot Gardiner explains I would like to take this opportunity to commitment, they are helping to secure why this is the case. thank our media partners, medici.tv, who the future of the Orchestra, ensuring that are broadcasting tonight’s concert live, our world-class artistic programme and youtube.com/lso and to Classic FM, who have recommended pioneering education and community A warm welcome to this evening’s LSO tonight’s concert to their listeners. The projects will thrive for years to come. concert at the Barbican, as we are joined by performance will also be streamed live on WELCOME TO TONIGHT’S GROUPS one of the Orchestra’s regular collaborators, the LSO’s YouTube channel, where it will lso.co.uk/legacies Sir John Eliot Gardiner.