Reconstructing Somerset Place: Slavery, Memory and Historical Consciousness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fun Facts Activities Experience the Park!

Activities Pettigrew State Park is located in the coastal region of North Carolina, 60 miles east of Greenville on a peninsula between the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds. It is situated on the shores of Lake Phelps, our state’s second largest natural lake. From the mysterious origins of the lake to artifacts from Native Americans, Pettigrew has a rich and fascinating natural and cultural history. Experience the Park! ■■Tundra swan ■■Snow goose Pettigrew State Park ■■Kingfisher 2252 Lake Shore Rd. ■■Black bear Creswell, NC 27928 The park is home ■■Bobcat 252-797-4475 to very large cypress ■■Muskrat [email protected] and sycamore trees. GPS: 35.788863, -76.40381 Some have openings ■■Zebra swallowtail large enough that whole families Fun Facts can stand ■■ The park was established in 1936. inside. ■■ The Algonquin Indians were said to be seasonal hunters to Lake Phelps. ■■ The north shore of Lake Phelps makes up one of the last old-growth forests in 30 dugout canoes have eastern NC. been located in the waters ■■ The average depth of Lake Phelps is 4.5 feet. of Lake Phelps. One is Maximum depth is 9 feet. 4,400 years old. ■■ At 16,000 acres, Lake Phelps makes up a great deal of Pettigrew State Park. ■■ The origins of Lake Phelps are a mystery. Theories include peat burn, underground spring, wind and wave action, meteor showers and glacier activity. Yellow Perch Largemouth Bass ■■ The park is named after the Pettigrew family, Catfish who owned a plantation on the lands of Pumpkinseed today’s Pettigrew State Park. The original home burned in 1869 but was rebuilt and later dismantled in the 1950’s. -

THE GREATEST SHOW on the EAST COAST North Carolina's

C a p t u r i n g C a r b o n • L e a r n i n g t o F l y • U n d e r w a t e r E a v e s d r o p p i n g • M e r c u r y R i s i n g CoastwatchN O R T H C A R O L I N A S E A G R A N T • S P R I N G • 2 0 2 0 • I S S U E 1 • $ 6 . 9 5 THE GREATEST SHOW ON THE EAST COAST North Carolina’s Nightscapes The Outer Albemarle Peninsula ofers some of the darkest skies on the U.S. Atlantic seaboard, with sites for unsurpassed stargazing and a nightscape experience full of wildlife at play under the music of the spheres. THE THE THE GREATEST SHOW ON THE EAST COAST New Journeys into SHOW the Heart of North Carolina’s Darkness DAVE SHAW The bufer around the Outer Albemarle Peninsula’s amazing nightscapes includes Ocracoke Island. GREATEST GREATEST ON EARTH Meredith Ross/VisitNC.com 6 coastwatch | spring 2020 | ncseagrant.org coastwatch | spring 2020 | ncseagrant.org 7 Welcome to the “Yellowstone of the East,” where the Gothic “It’s truly a magic place,” he says, “once you get off the main South meets the galaxy. Here on the Outer Albemarle Peninsula, you can highways.” stare into the soul of the Milky Way, a gash of glitter across the night sky Riggs frst heard the “Yellowstone of the East” description of the that formed billions of years before our planet. -

Education Recourse Packet for Teachers Dear Educators, Thank

Education Recourse Packet for Teachers Dear Educators, Thank you for your interest in Somerset Place State Historic Site’s educational guided tours! We hope this packet will be helpful as you decide whether to bring your class to our historic site. This packet is designed to provide information about visiting our site, as well as ideas for activities to implement in your classroom before and after your field trip. Hopefully these activities will prepare the students for their trip, as well as reinforce what they learned during their experience at Somerset Place. Sincerely, The Staff of Somerset Place State Historic Site Phone: 252-797-4560 Email: [email protected] Website: https://historicsites.nc.gov/all-sites/somerset-place Today, Somerset Place State Historic Site is situated on 31 acres in Washington County, North Carolina. Most of the tour consists of walking outdoors and through seven buildings. We ask that visitors remember to wear comfortable walking shoes. In the spring and summer, an afternoon rain shower is not uncommon, and we do give guided tours in the rain. Please be prepared for this possibility. If you have scheduled a guided tour, we ask that your group arrives no later than 15 minutes before your scheduled start time. This will give you the opportunity to walk from the parking lot to our visitor center and for the group leader to fill out a brief group tour form. Since our restroom facilities are limited, allow students time to use the restrooms prior to the tour. We recommend allowing 15-30 minutes for this if you have a large group. -

Local Historic Landmark Designations

Item No: AIR - 0080 Staff Responsible: Lisa McCarter Agenda Date: 10 Nov 2015 Prepared For: RE: DESCRIPTION Local Historic Landmark Designations MEMORANDUM TO: MAYOR AND BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS FROM: LISA MCCARTER, PLANNER II SUBJECT: LOCAL HISTORIC LANDMARK DESIGNATIONS DATE: NOVEMBER 10, 2015 CC: MELODY SHULER, WARREN WOOD Request: BOC consideration to vote on the commencement of local historic landmark designation reports for four town owned structures: Duncan McDonald House (115 McDonald Street), Niven‐Price Mercantile Building (216 W. North Main Street), The Meeting Place (209 W. South Main Street) and the Waxhaw Water Tank (113 McDonald Street). Benefits of Local Landmark Designation: Local Historic Designation of structures provides economic benefits, tourism and placemaking benefits, and community‐building benefits. The Town of Waxhaw wishes to preserve the unique character of Waxhaw for generations to come—including its historic buildings. Historic buildings are integral to an excellent Waxhaw visitor experience. Historic structures that are aesthetically cohesive and well promoted can be a community’s most important attraction and reinforce Waxhaw’s unique sense of place. The retention of our historic structures is a way to attract tourist dollars that contribute to the local economy. Waxhaw Local Landmarks: There are currently three designated local historic landmarks in Waxhaw. These are the Waxhaw Woman’s Club (200 E. South Main Street), the Cockinos Building/Antique Mart (portion of the 100 block of W. South Main Street), and the downtown overhead pedestrian bridge over the CSX railroad line. Local Landmark Designation vs. National Historic Registry Listing: National Historic Registry listings are mostly honorary and do not impose any restrictions that prevent private property owners from making changes to their buildings or demolishing them. -

John White, Roanoke Rescue Voyage (Lost Colony)

JOHN WHITE’S ATTEMPT Birmingham (AL) PL TO RESCUE THE ROANOKE COLONISTS Carolina coast__1590 John White, The Fifth Voyage of M. John White into the West Indies and Parts of America called Virginia, in the year 1590 *___Excerpts__ In 1587 John White led the third Raleigh-financed voyage to Roanoke Island; it was the first to include women and children to create a stable English colony on the Atlantic coast. Soon the colonists agreed that White should return to England for supplies. White was unable to return to Roanoke for three years, however, Theodore de Bry, America pars, Nunc Virginia dicta, due to French pirate attacks and England’s war with Spain. engraving after watercolor by John White, 1590 Finally, in August 1590, White returned to Roanoke Island. The 20 of March the three ships the Hopewell, the John Evangelist, and the Little John, put to sea from Plymouth [England] with two small shallops.1 . AUGUST. On the first of August the wind scanted [reduced], and from thence forward we had very foul weather with much rain, thundering, and great spouts, which fell round about us nigh unto our ships. The 3 we stood again in for the shore, and at midday we took the height of the same. The height of that place we found to be 34 degrees of latitude. Towards night we were within three leagues of the low sandy islands west of Wokokon. But the weather continued so exceeding foul, that we could not come to an anchor near the coast: wherefore we stood off again to sea until Monday the 9 of August. -

The Rich Heritage African Americans North Carolina

THE RICH HERITAGE OF AFRICAN NORTH CAROLINA AMERICANS HERITAGE IN North Carolina Division of Tourism, Film and Sports Development Department of Commerce NORTH 301 N. Wilmington Street, Raleigh, NC 27601-2825 1-800-VISIT NC • 919-733-8372 www.visitnc.com CAROLINA 100,000 copies of this document were printed in the USA at a cost of $115,000 or $1.15 each. Dear Friends, North Carolina is a state rich in diversity. And it is blessed with an even richer heritage that is just waiting to be explored. Some of the most outstanding contributions to our state’s heritage are the talents and achievements of African Americans. Their legacy embraces a commitment to preserving, protecting, and building stronger communities. The North Carolina Department of Commerce and Department of Cultural Resources acknowledge I invite you to use “The Rich Heritage of African Americans in North Carolina” as a guide to explore the history the generous support of the following companies in the production of this booklet: of the African American community in our state. If you look closely, you will find that schools, churches, museums, historic sites, and other landmarks tell the powerful story of African Americans in North Carolina. Food Lion Remember that heritage is not just a thing of the past. It is created every day. And by visiting these sites, you can be part Miller Brewing Company of it. Consider this an invitation to discover and celebrate the history that is the African American community. Philip Morris U.S.A. Its presence has made – and continues to make – North Carolina a better place to be. -

Bibliography of North Carolina Underwater Archaeology

i BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH CAROLINA UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY Compiled by Barbara Lynn Brooks, Ann M. Merriman, Madeline P. Spencer, and Mark Wilde-Ramsing Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Division of Archives and History April 2009 ii FOREWARD In the forty-five years since the salvage of the Modern Greece, an event that marks the beginning of underwater archaeology in North Carolina, there has been a steady growth in efforts to document the state’s maritime history through underwater research. Nearly two dozen professionals and technicians are now employed at the North Carolina Underwater Archaeology Branch (N.C. UAB), the North Carolina Maritime Museum (NCMM), the Wilmington District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE), and East Carolina University’s (ECU) Program in Maritime Studies. Several North Carolina companies are currently involved in conducting underwater archaeological surveys, site assessments, and excavations for environmental review purposes and a number of individuals and groups are conducting ship search and recovery operations under the UAB permit system. The results of these activities can be found in the pages that follow. They contain report references for all projects involving the location and documentation of physical remains pertaining to cultural activities within North Carolina waters. Each reference is organized by the location within which the reported investigation took place. The Bibliography is divided into two geographical sections: Region and Body of Water. The Region section encompasses studies that are non-specific and cover broad areas or areas lying outside the state's three-mile limit, for example Cape Hatteras Area. The Body of Water section contains references organized by defined geographic areas. -

North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources State Historic Preservation Office Ramona M

North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources State Historic Preservation Office Ramona M. Bartos, Administrator Governor Roy Cooper Office of Archives and History Secretary Susi H. Hamilton Deputy Secretary Kevin Cherry July 31, 2020 Braden Ramage [email protected] North Carolina Army National Guard 1636 Gold Star Drive Raleigh, NC 27607 Re: Demolish & Replace NC Army National Guard Administrative Building 116, 116 Air Force Way, Kure Beach, New Hanover County, GS 19-2093 Dear Mr. Ramage: Thank you for your submission of July 8, 2020, transmitting the requested historic structure survey report (HSSR), “Historic Structure Survey Report Building 116, (former) Fort Fisher Air Force Radar Station, New Hanover County, North Carolina”. We have reviewed the HSSR and offer the following comments. We concur that with the findings of the report, that Building 116 (NH2664), is not eligible for the National Register of Historic Places for the reasons cited in the report. We have no recommendations for revision and accept this version of the HSSR as final. Additionally, there will be no historic properties affected by the proposed demolition of Building 116. Thank you for your cooperation and consideration. If you have questions concerning the above comment, contact Renee Gledhill-Earley, Environmental Review Coordinator, at 919-814-6579 or [email protected]. In all future communication concerning this project, please cite the above referenced tracking number. Sincerely, Ramona Bartos, Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer cc Megan Privett, WSP USA [email protected] Location: 109 East Jones Street, Raleigh NC 27601 Mailing Address: 4617 Mail Service Center, Raleigh NC 27699-4617 Telephone/Fax: (919) 814-6570/807-6599 HISTORIC STRUCTURES SURVEY REPORT BUILDING 116, (FORMER) FORT FISHER AIR FORCE RADAR STATION New Hanover County, North Carolina Prepared for: North Carolina Army National Guard Claude T. -

North Carolina Insi $6 September1986 Vol

North Carolina Insi $6 September1986 Vol. 9 No.t 2 N.C. Center for Public Policy Research Board of Directors The North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research is an independent research and educational institution formed Chairman Thad L. Beyle to study state government policies and practices without partisan bias or political intent. Its purpose is to enrich Vice Chair Keith Crisco the dialogue between private citizens and public officials, and its constituency is the people of this state. The Center's broad Secretary institutional goal is the stimulation of greater interest in public Karen E. Gottovi affairs and a better understanding of the profound impact Treasurer state government has each day on everyone in North V. B. (Hawk) Johnson Carolina. Thomas L. Barringer A non-profit, non-partisan organization, the Center was Daniel T. Blue, Jr. formed in 1977 by a diverse group of private citizens "for the Maureen Clark purpose of gathering, analyzing and disseminating informa- Frances Cummings Francine Delany tion concerning North Carolina's institutions of government." Walter DeVries It is guided by a self-electing Board of Directors and has Charles Z. Flack, Jr. Joel L. Fleishman individual and corporate members across the state. Virginia Ann Foxx Center projects include the issuance of special reports Robert Gordon on major policy questions; the publication of a quarterly R. Darrell Hancock William G. Hancock, Jr. magazine called North Carolina Insight; the production of a Mary Hopper symposium or seminar each year; and the regular participa- Sandra L. Johnson tion of members of the staff and the Board in public affairs Betty Ann Knudsen Helen H. -

FALL/WINTER 2020/2021 – Tuesday Schedule Morning Class: 10:00 – 12:00 and Afternoon Class: 1:30 – 3:30

FALL/WINTER 2020/2021 – Tuesday Schedule Morning Class: 10:00 – 12:00 and Afternoon Class: 1:30 – 3:30 September 29, 2020 The Magic of Audrey Janna Trout (Extra session added to our regular schedule, to practice using Zoom.) The essence of chic and a beautiful woman, Audrey Hepburn, brought a certain “magic” quality to the screen. Synonymous with oversized sunglasses and the little black dress, many are unaware of the hardships she endured while growing up in Nazi-occupied Holland. Starring in classic movies such as Sabrina, My Fair Lady, and of course, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Audrey Hepburn brought effortless style and grace to the silver screen. Following the many Zoom training opportunities offered in the last two weeks of September, let’s put our training to the test! The Technology Team recommended we conduct the first zoom class without a live presenter so we can ensure that everything is working correctly to set us up for a successful semester. Below is the format of our first LIFE@ Elon class on Zoom – enjoy this documentary about the one and only Audrey Hepburn! Open Class On Tuesday mornings, you will receive an email with a link for the class. (If the presenter has a handout, we will attach it to the email.) Twenty minutes before the start of class, we will have the meeting open so you can click on the link to join. Kathryn Bennett, the Program Coordinator, will be there to greet members as they are logging on, and Katie Mars, the Technology Specialist, will be present, as well. -

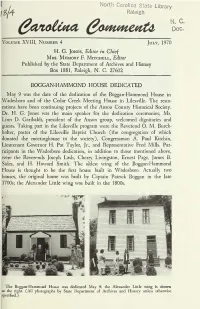

Ally Two Houses, the Original Home Was Built by Captain Patrick Boggan in the Late 1700S; the Alexander Little Wing Was Built in the 1800S

North Carolina State Library Raleigh N. C. Doc. VoLUME XVIII, NuMBER 4 JULY, 1970 H. G. JoNES, Editor in Chief MRs. MEMORY F. MITCHELL, Editor Published by the State Department of Archives and History Box 1881, Raleigh, N. C. 27602 BOGGAN-HAMMOND HOUSE DEDICATED May 9 was the date of the dedication of the Boggan-Hammond House in Wadesboro and of the Cedar Creek Meeting House in Lilesville. The resto rations have been continuing projects of the Anson County Historical Society. Dr. H. G. Jones was the main speaker for the dedication ceremonies; Mr. Linn D. Garibaldi, president of the Anson group, welcomed dignitaries and guests. Taking part in the Lilesville program were the Reverend 0. M. Burck halter, pastor of the Lilesville Baptist Church (the congregation of which donated the meetinghouse to the society), Congressman A. Paul Kitchin, Lieutenant Governor H. Pat Taylor, Jr., and Representative Fred Mills. Par ticipants in the Wadesboro dedication, in addition to those mentioned above, were the Reverends Joseph Lash, Cherry Livingston, Ernest Page, James B. Sides, and H. Howard Smith. The oldest wing of the Boggan-Hammond House is thought to be the first house built in Wadesboro. Actually two houses, the original home was built by Captain Patrick Boggan in the late 1700s; the Alexander Little wing was built in the 1800s. The Boggan-H3mmond House was dedicated May 9; the Alexander Little wing is shown at the right. (All photographs by State Department of Archives and History unless otherwise specified.) \ Pictured above is the restored Cedar Creek Meeting House. FOUR MORE NORTH CAROLINA STRUCTURES BECOME NATIONAL LANDMARKS Four North Carolina buildings were designated National Historic Landmarks by the Department of the Interior in May. -

North Carolina General Assembly 1979 Session

NORTH CAROLINA GENERAL ASSEMBLY 1979 SESSION RESOLUTION 21 HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 1128 A JOINT RESOLUTION DEDICATING PROPERTIES AS PART OF THE STATE NATURE AND HISTORIC PRESERVE. Whereas, Article XIV, Section 5 of the North Carolina Constitution authorizes the dedication of State and local government properties as part of the State Nature and Historic Preserve, upon acceptance by resolution adopted by a vote of three fifths of the members of each house of the General Assembly; and Whereas, the North Carolina General Assembly enacted the State Nature and Historic Preserve Dedication Act, Chapter 443, 1973 Session Laws to prescribe the conditions and procedures under which properties may be specially dedicated for the purposes enumerated by Article XIV, Section 5 of the North Carolina Constitution; and Whereas, the 1973 General Assembly sought to declare units of the State park system and certain historic sites as parts of the State Nature and Historic Preserve by adoption of Resolution 84 of the 1973 Session of the General Assembly; and Whereas, the effective date of 1973 Session Laws, Resolution 84 was May 10, 1973, while the effective date of Article XIV, Section 5, of the North Carolina Constitution and Chapter 443 of the 1973 Session Laws was July 1, 1973, thereby making Resolution 84 ineffective to confer the intended designation to the properties cited therein; and Whereas, the General Assembly desires to reaffirm its intention to accept certain properties enumerated in Resolution 84 of the 1973 General Assembly and to add certain properties acquired since the adoption of said Resolution as part of the State Nature and Historic Preserve; and Whereas, the Council of State pursuant to G.S.