Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Thomas Wingfold, Curate, by George Macdonald (#25 in Our Series by George Macdonald)

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Thomas Wingfold, Curate, by George MacDonald (#25 in our series by George MacDonald) Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Thomas Wingfold, Curate Author: George MacDonald Release Date: June, 2004 [EBook #5976] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on October 2, 2002] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, THOMAS WINGFOLD, CURATE *** Charles Franks, Charles Aldarondo, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. THOMAS WINGFOLD, CURATE. By George MacDonald, LL.D. IN THREE VOLUMES. VOL I. THOMAS WINGFOLD, CURATE. CHAPTER I. HELEN LINGARD. A swift, gray November wind had taken every chimney of the house for an organ-pipe, and was roaring in them all at once, quelling the more distant and varied noises of the woods, which moaned and surged like a sea. -

John Valadez Interviewed by Karen Mary Davalos on November 19 and 21, and December 3, 7, and 12, 2007

CSRC ORAL HISTORIES SERIES NO. 10, DECEMBER 2013 JOHN VALADEZ INTERVIEWED BY KAREN MARY DAVALOS ON NOVEMBER 19 AND 21, AND DECEMBER 3, 7, AND 12, 2007 John Valadez is a painter and muralist. A graduate of East Los Angeles College and California State University, Long Beach, he is the recipient of many grants, commissions, and awards, including those from the Joan Mitchell Foundation, the California Arts Commission, and the Fondation d’Art de la Napoule, France. His work has appeared in exhibitions nationwide and is in the permanent collection of major museums; among them are National Museum of American Art at the Smithsonian, Bass Museum of Art in Miami Beach, Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, Mexican Museum in Chicago, and Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Valadez lives and works in Los Angeles. Karen Mary Davalos is chair and professor of Chicana/o studies at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. Her research interests encompass representational practices, including art exhibition and collection; vernacular performance; spirituality; feminist scholarship and epistemologies; and oral history. Among her publications are Yolanda M. López (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2008); “The Mexican Museum of San Francisco: A Brief History with an Interpretive Analysis,” in The Mexican Museum of San Francisco Papers, 1971–2006 (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2010); and Exhibiting Mestizaje: Mexican (American) Museums in the Diaspora (University of New Mexico Press, 2001). This interview was conducted as part of the L.A. Xicano project. Preferred citation: John Valadez, interview with Karen Mary Davalos, November 19 and 21, and December 3, 7, and 12, 2007, Los Angeles, California. -

Welcome, We Have Been Archiving This Data for Research And

Welcome, To our MP3 archive section. These listings are recordings taken from early 78 & 45 rpm records. We have been archiving this data for research and preservation of these early discs. ALL MP3 files can be sent to you by email - $2.00 per song Scroll until you locate what you would like to have sent to you, via email. If you don't use Paypal you can send payment to us at: RECORDSMITH, 2803 IRISDALE AVE RICHMOND, VA 23228 Order by ARTIST & TITLE [email protected] H & H - Deep Hackberry Ramblers - Crowley Waltz Hackberry Ramblers - Tickle Her Hackett, Bobby - New Orleans Hackett, Buddy - Advice For young Lovers Hackett, Buddy - Chinese Laundry (Coral 61355) Hackett, Buddy - Chinese Rock and Egg Roll Hackett, Buddy - Diet Hackett, Buddy - It Came From Outer Space Hackett, Buddy - My Mixed Up Youth Hackett, Buddy - Old Army Routine Hackett, Buddy - Original Chinese Waiter Hackett, Buddy - Pennsylvania 6-5000 (Coral 61355) Hackett, Buddy - Songs My Mother Used to Sing To Who 1993 Haddaway - Life (Everybody Needs Somebody To Love) 1993 Haddaway - What Is Love Hadley, Red - Brother That's All (Meteor 5017) Hadley, Red - Ring Out Those Bells (Meteor 5017) 1979 Hagar, Sammy - (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay 1987 Hagar, Sammy - Eagle's Fly 1987 Hagar, Sammy - Give To Live 1984 Hagar, Sammy - I Can't Drive 55 1982 Hagar, Sammy - I'll Fall In Love Again 1978 Hagar, Sammy - I've Done Everything For You 1978 1983 Hagar, Sammy - Never Give Up 1982 Hagar, Sammy - Piece Of My Heart 1979 Hagar, Sammy - Plain Jane 1984 Hagar, Sammy - Two Sides -

Curtis Johnson and Samuel Jones Interviewer

Date: 6/30/2004 Interviewees: Curtis Johnson and Samuel Jones Interviewer: Jacob Rabinbach Location: Stax Museum of American Soul Music, Memphis, TN Collection: Stax Museum Oral Histories Notes: Interviewer: I’m going to have to ask you guys to speak up a bit because we couldn’t figure out – we don’t have the technology yet to have microphones for this thing, unfortunately. So we just gotta pick it up in here. I just want to say thanks for coming, I really appreciate it, I'm sorry you guys had to wait. I'd just like to ask, everybody, you know, what is soul music for you guys, how do you define it? Jones: Soul Music... It's gotta be from the heart, straight from the heart, you know, playing what you feel. And the way we did it here, to define soul, it was just everybody getting together and chilling, making it happen, with not a lot of arrangements, not a lot of sheet music. It was just like coming together and making it happen. Soul, you know, is just a certain feel, when you get those goose bumps and you know when it's there. [01:00] Interviewer: When was it there for you guys? Johnson: Well, we started doing background here at Stax, but we started in high school. We went to school together, and we started in high school with a little group, and we thought we had it together long before we really did. Interviewer: I think that’s how it is in high school. -

For Additional Information Contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 Or

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. HANK JONES NEA Jazz Master (1989) Interviewee: Hank Jones (July 31, 1918 – May 16, 2010) Interviewer: Bill Brower Date: November 26-27, 2004 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, pp. 134 Hank Jones: I was over there for about two and a half weeks doing a promotional tour. I had done a couple of CDs; one was with my brother Elvin and Richard Davis, the bass player. They made – – I think they made two releases from that date. And I did another date with Jack DeJohnette and John Patitucci. But, these two albums were the objects of the promotion. I mean, they promote very, very heavily everyday. I must have had 40 interviews and about 30 record signings at the record shops, plus all of the recording. We did seven concerts and people inevitably want the records, CDs of the concert for us to sign. I have a trio over there, with Jimmy Cobb and John Fink. It was called, “The Great Jazz Trio.” It was not my name, but the Japanese have special names for everything, you know? That's only one in a series of tree others which he called the great jazz trio. The first one was Ron Carter, Tony Williams and myself. But, there had been a succession of different changes in personnel. It changed about six times. The current one was Jimmy Cobb and Dave Fink--Oh, the cookies have arrived and not a minute too soon. -

Paul the Peddler Or the Fortunes of a Young Street Merchant

PAUL THE PEDDLER OR THE FORTUNES OF A YOUNG STREET MERCHANT BY HORATIO ALGER, JR. BIOGRAPHY AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Horatio Alger, Jr., an author who lived among and for boys and himself remained a boy in heart and association till death, was born at Revere, Mass., January 13, 1834. He was the son of a clergyman, was graduated at Harvard College in 1852, and at its Divinity School in 1860 and was pastor of the Unitarian Church at Brewster, Mass., in 1862-66. In the latter year he settled in New York and began drawing public attention to the condition and needs of street boys. He mingled with them, gained their confidence showed a personal concern in their affairs, and stimulated them to honest and useful living. With his first story he won the hearts of all red-blooded boys everywhere, and of the seventy or more that followed over a million copies were sold during the author's lifetime. In his later life he was in appearance a short, stout, bald-headed man, with cordial manners and whimsical views of things that amused all who met him. He died at Natick, Mass., July 18, 1899. Mr. Alger's stories are as popular now as when first published, because they treat of real live boys who were always up and about-just like the boys found everywhere to-day. They are pure in tone and inspiring in influence, and many reforms in the juvenile life of New York may be traced to them. Among the best known are: Strong and Steady; Strive and Succeed; Try and Trust; Bound to Rise; Risen from the Ranks; Herbert Carter's Legacy; Brave and Bold; Jack's Ward; Shifting for Himself; Wait and Hope; Paul the Peddler; Phil the Fiddler; Slow and Sure; Julius the Street Boy; Tom the Bootblack; Struggling Upward, Facing the World; The Cash Boy; Making His Way; Tony the Tramp; Joe's Luck; Do and Dare; Only an Irish Boy; Sink or Swim; A Cousin's Conspiracy; Andy Gordon; Bob Burton; Harry Vane; Hector's Inheritance; Mark Mason's Triumph; Sam's Chance; The Telegraph Boy; The Young Adventurer; The Young Outlaw; The Young Salesman, and Luke Walton. -

Isley Brothers Love Songs Album Zip Download Soul Funk Paradise

isley brothers love songs album zip download soul funk paradise. The Isley Brothers - The Brothers Isley - 1969 1 . I Turned You On 2 . Vacuum Cleaner 3 . I Got To Get Myself Together 4 . Was It Good For You? 5 . The Blacker The Berrie (a-k-a- Black Berries) 6 . My Little Girl 7 . Get Down Off Of The Train 8 . Holding On 9 . Feels Like The World. The Isley Brothers - Get Into Something - 1970 1 . Get Into Something 2 . Freedom 3 . Take Inventory 4 . Keep on Doin' 5 . Girls Will Be Girls 6 . I Need You So 7 . If He Can You Can 8 . I Got to Find Me One 9 . Beautiful 10 . Bless Your Heart. The Isley Brothers - It's Your Thing - 1970 1 . I Know Who You Been Socking It 2 . Somebody Been Messin' 3 . Save Me 4 . I Must Be Losing My Touch 5 . Feel Like The World 6 . It's Your Thing 7 . Give The Women What They Want 8 . Love Is What You Make It 9 . Don't Give It Away 10 . He's Got Your Love. The Isley Brothers - Brother, Brother, Brother - 1972 1 . Brother, Brother 2 . Put A Little Love In Your Heart 3 . Sweet Season / Keep On Walkin' 4 . Work To Do 5 . Pop That Thang 6 . Lay Away 7 . It's Too Late 8 . Love Put Me On The Corner. The Isley Brothers - 3 + 3 - 1973 1 . That Lady 2 . Don't Let Me Be Lonely Tonight 3 . If You Were There 4 . You Walk Your Way 5 . Listen To The Music 6 . -

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream HUNTER S. THOMPSON 1 To Bob Geiger, for reasons that need not be explained here —and to Bob Dylan, for Mister Tambourine Man 2 Table of Contents Part 1 1. 2. The Seizure of $300 from a Pig Woman in Beverly Hills 3. Strange Medicine on the Desert . a Crisis of Confidence 4. Hideous Music and the Sound of Many Shotguns . Rude Vibes on a Saturday Evening in Vegas 5. Covering the Story . A Glimpse of the Press in Action . Ugliness & Failure 6. A Night on the Town . Confrontation at the Desert Inn . Drug Frenzy at the Circus-Circus 7. Paranoid Terror . and the Awful Specter of Sodomy . A Flashing of Knives and Green Water 8. “Genius ‘Round the World Stands Hand in Hand, and One Shock of Recognition Runs the Whole Circle ‘Round” 9. No Sympathy for the Devil . Newsmen Tortured? . Flight into Madness 10. Western Union Intervenes: A Warning from Mr. Heem . New Assignment from the Sports Desk and a Savage Invitation from the Police 11. Aaawww, Mama, Can This Really Be the End? . Down and Out in Vegas, with Amphetamine Psychosis Again? 12. Hellish Speed . Grappling with the California Highway Patrol . Mano a Mano on Highway 61 Part 2 1. 2. Another Day, Another Convertible . & Another Hotel Full of Cops 3. Savage Lucy . ‘Teeth Like Baseballs, Eyes Like Jellied Fire’ 4. No Refuge for Degenerates . Reflections on a Murderous Junkie 5. A Terrible Experience with Extremely Dangerous Drugs 6. Getting Down to Business . -

Alex's Guitar Tech

•• _ ...... .- 4I_~ ----'---------___ -...."'--- __.4-......-...--.._ ............. .....r--~-- ISSUE No.44 - AUTUMN/FALL 1998 ~._4IL~ _ •• _ .... __ It " .I -----------~--------~--~-..~--------~~.pl.--t---~----~----~- to, Hello and welcome to the latest 'Spirit Of Gold Award. A complete set of Rush' . Without doubt the highlight of this re- mastered CDs, various T.shirts issue is our exclusive interview with Jimmy some black and white promo photos Johnson, (see opposite). It was a real pleasure and some promo CDs. Worth coming talking to a very open and generous man (thanks just for a chance of winning one must go to Russ Ryan for introducing us) cheers of those. We are lining up a big mate! We promised you three exclusive interviews surprise (if it works out) as well last issue; however the promised Larry Gowan and nudge nudge wink wink! There will Kevin Shirley interviews were squeezed out by also be a Rock Disco and another the length of the Jimmy Johnson one, they will live band playing provided by the of course appear in the next issue No: 45 which university themselves. This will will be with you in November. help keep our costs down re-bar staff and security etc. Hope to The response to the readers poll which we sent see you all on the 19th of the 9th. out with the last issue has been less than enthusiastic, hence we will not be bringing you Details of the forthcoming live the result of it at the convention as we stated album continue to emerge (all un last issue. Instead you will find the poll once confirmed) The title is 'Different again enclosed with this issue, so please take Stages' one CD will feature a the time to fill it out and mail it to us at show from the 'Kings' tour London the address on the right. -

The Soul of 1971: Rethinking Understandings of Protest Music

THE SOUL OF 1971: RETHINKING UNDERSTANDINGS OF PROTEST MUSIC by Zack Harrison Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2017 © Copyright by Zack Harrison, 2017 DEDICATION In memory of my Grandma Peggy. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................ iv ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ v LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................... vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. vii CHAPTER ONE: Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER TWO: The Isley Brothers: Ohio/Machine Gun .............................................. 12 CHAPTER THREE: Marvin Gaye: What’s Going On ..................................................... 27 CHAPTER FOUR: Gil Scott-Heron: The Revolution Will Not Be Televised ................. 53 CHAPTER FIVE: Conclusion ........................................................................................... 69 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................. 75 APPENDIX A ................................................................................................................. -

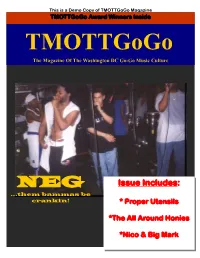

Issue Includes: ...Them Bammas Be Crankin! * Proper Utensils

This is a Demo Copy of TMOTTGoGo Magazine TMOTTGoGo Award Winners Inside TMOTTGoGo The Magazine Of The Washington DC Go-Go Music Culture NEG Issue Includes: ...them bammas be crankin! * Proper Utensils *The All Around Honies *Nico & Big Mark TMOTTGoGo 1 This is a Demo Copy of TMOTTGoGo Magazine FULL PAGE ADVERTISEMENT INSIDE COVER GOES HERE $125.00 TMOTTGoGo 2 This is a Demo Copy of TMOTTGoGo Magazine Georgia Avenue, that the Go-Go Community is Vender’s Market, an essential part of my life, Children's Hospital, and I am blessed to have Walter Reed, UDC, been/be a part of it. That’s the Howard University, purpose of TMOTTGoGo -- to Children's Museum, educate, uplift and promote Stuff, Newsbag, our culture with the Galludet, Columbia positiveness that it deserves. Hospital For Women, The bottom line is, I don’t Southeast House, Job care what you are doing in life Corp, etc. I mean, the -- whether you've moved away Having grown up in this list goes on and on. and are doing well with community, I take pride to And lets not forget about movies, such as "What’s Love have been a recipient, as well the music that has paved our Got To Do With It" or television as contributor in the way, such as, Duke Ellington, programs, such as "In The achievements that has been Roberta Flack, Marvin Gaye, Heat Of The Night" -- whether accomplished throughout the The Ambassadors, Simba, The you’re performing on shows many years. Soul Searchers, Experience On Broadway, Las Vegas and This is a very historical Unlimited, Fate’s Destiny, across the world -- or whether community that has furnished The Stratocasters, as well as you’re performing on tour with such historics as the Black others. -

Over 1000 Breakbeat List

Over 1000 Breakbeat List 1. Stop - Wake Up 2. Superman Ivy - Yes Yes Ya'll 3. Superman Ivy - Yes Yes Ya'll (Remix) 4. Superman Ivy - Yes Yes Ya'll (Acapella) 5. Superman Ivy - Yes Yes Ya'll (Instrumental) 6. Tha Alkaholiks - Make Room 7. Thalia - The Mexican (Disco Circus Remix) 8. The 45 King - The 900 Number 9. The Beginning Of The End - Funky Nassau 10. The Meters - Same Old Thing 11. The Poets Of The Rhythm - North Carolina 12. The Ying Yang Technique - LUDI 13. Black Eyed Peas - They Don't Want Music 14. Third World Lover - Kid Koala 15. Ultramagnetic MC'S - One To Grow On 16. Visionaries - Crop Circles 17. Watch Out Now - Beatnuts 18. Yellow Sunshine 19. Yoshida Brothers - Storm 20. Da Boogie Crew - You Boys (Remix) 21. Zion-I & The Grouch - Trains & Planes 22. RJD2 - The Horror 23. Rob Dougan - Clubbed To Death 24. RUN DMC - It's Tricky 25. Safri Duo - Rise (Remix) 26. Sapo - Been Had 27. Scooter - Bboys/Bgirls Rock Tha House 28. Skrip Breaks - Enemy Crush 29. Sorea - Soul In Panic 30. Souls Of Mischief - 93 Till Infinity 31. Southside Rockers - Jump 32. Stetsasonic - Talkin' All That Jazz 33. Stetsasonic - The Hip Hop Band 34. Superman Ivy - Rivers Crew Theme 35. Superman Ivy - Rivers Crew Theme (Instrumental) 36. Superman Ivy - Rivers Crew Theme (Acapella) 37. Superman Ivy - Seoul Futureshock 38. Superman Ivy - The Freshest Ivy 39. Superman Ivy - The Freshest Ivy (Acapella) 40. Superman Ivy - The Freshest Ivy (Instrumental) 41. Mark Ronson Feat. Ghostface Killah, Nate Dogg, Trife - Ooh Wee 42.