Film Location Location Location

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

Classic Frenchfilm Festival

Three Colors: Blue NINTH ANNUAL ROBERT CLASSIC FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL Presented by March 10-26, 2017 Sponsored by the Jane M. & Bruce P. Robert Charitable Foundation A co-production of Cinema St. Louis and Webster University Film Series ST. LOUIS FRENCH AND FRANCOPHONE RESOURCES WANT TO SPEAK FRENCH? REFRESH YOUR FRENCH CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE? CONTACT US! This page sponsored by the Jane M. & Bruce P. Robert Charitable Foundation in support of the French groups of St. Louis. Centre Francophone at Webster University An organization dedicated to promoting Francophone culture and helping French educators. Contact info: Lionel Cuillé, Ph.D., Jane and Bruce Robert Chair in French and Francophone Studies, Webster University, 314-246-8619, [email protected], facebook.com/centrefrancophoneinstlouis, webster.edu/arts-and-sciences/affiliates-events/centre-francophone Alliance Française de St. Louis A member-supported nonprofit center engaging the St. Louis community in French language and culture. Contact info: 314-432-0734, [email protected], alliancestl.org American Association of Teachers of French The only professional association devoted exclusively to the needs of French teach- ers at all levels, with the mission of advancing the study of the French language and French-speaking literatures and cultures both in schools and in the general public. Contact info: Anna Amelung, president, Greater St. Louis Chapter, [email protected], www.frenchteachers.org Les Amis (“The Friends”) French Creole heritage preservationist group for the Mid-Mississippi River Valley. Promotes the Creole Corridor on both sides of the Mississippi River from Ca- hokia-Chester, Ill., and Ste. Genevieve-St. Louis, Mo. Parts of the Corridor are in the process of nomination for the designation of UNESCO World Heritage Site through Les Amis. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

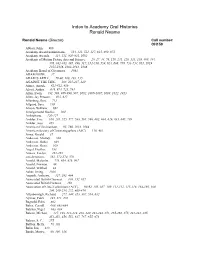

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame Ronald Neame (Director) Call number: OH159 Abbott, John, 906 Academy Award nominations, 314, 321, 511, 517, 935, 969, 971 Academy Awards, 314, 511, 950-951, 1002 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science, 20, 27, 44, 76, 110, 241, 328, 333, 339, 400, 444, 476, 482-483, 495, 498, 517, 552-556, 559, 624, 686, 709, 733-734, 951, 1019, 1055-1056, 1083-1084, 1086 Academy Board of Governors, 1083 ADAM BEDE, 37 ADAM’S APPLE, 79-80, 100, 103, 135 AGAINST THE TIDE, 184, 225-227, 229 Aimee, Anouk, 611-612, 959 Alcott, Arthur, 648, 674, 725, 784 Allen, Irwin, 391, 508, 986-990, 997, 1002, 1006-1007, 1009, 1012, 1013 Allen, Jay Presson, 925, 927 Allenberg, Bert, 713 Allgood, Sara, 239 Alwyn, William, 692 Amalgamated Studios, 209 Ambiphone, 126-127 Ambler, Eric, 166, 201, 525, 577, 588, 595, 598, 602, 604, 626, 635, 645, 709 Ambler, Joss, 265 American Film Institute, 95, 766, 1019, 1084 American Society of Cinematogaphers (ASC), 118, 481 Ames, Gerald, 37 Anderson, Mickey, 366 Anderson, Robin, 893 Anderson, Rona, 929 Angel, Heather, 193 Ankers, Evelyn, 261-263 anti-Semitism, 562, 572-574, 576 Arnold, Malcolm, 773, 864, 876, 907 Arnold, Norman, 88 Arnold, Wilfred, 88 Asher, Irving, 1026 Asquith, Anthony, 127, 292, 404 Associated British Cinemas, 108, 152, 857 Associated British Pictures, 150 Association of Cine-Technicians (ACT), 90-92, 105, 107, 109, 111-112, 115-118, 164-166, 180, 200, 209-210, 272, 469-470 Attenborough, Richard, 277, 340, 353, 387, 554, 632 Aylmer, Felix, 185, 271, 278 Bagnold, Edin, 862 Baker, Carroll, 680, 883-884 Balchin, Nigel, 683, 684 Balcon, Michael, 127, 198, 212-214, 238, 240, 243-244, 251, 265-266, 275, 281-282, 285, 451-453, 456, 552, 637, 767, 855, 878 Balcon, S. -

Bafta Los Angeles

Sponsorship Opportunities BAFTA LOS ANGELES THE BRITISH ACADEMY OF FILM AND TELEVISION ARTS SUPPORTS, DEVELOPS AND PROMOTES THE ART FORMS OF THE MOVING IMAGE BY IDENTIFYING AND REWARDING EXCELLENCE, INSPIRING PRACTITIONERS AND BENEFITING THE PUBLIC. As the only Anglo-American professional organization founded to promote and advance original work in film, television and interactive media, The British Academy of Film and Television Arts Los Angeles serves as a link between the Hollywood and British production and entertainment business communities. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ A California non-profit public benefit corporation, BAFTA Los Angeles is a local organization with a global reach. As the L.A. branch of the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, headquartered in London, we represent not only our 1,200 members, but the full 6,500 Academy members based in the United Kingdom, New York and Los Angeles. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Membership in the Academy is both highly sought after and highly exclusive – applicants must be proposed and seconded by existing Academy members and thus represent the very top professionals in their various fields; from award winning writers, actors and directors, to key managers, network and studio executives and agents. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ We host stellar parties and awards -

A Mode of Production and Distribution

Chapter Three A Mode of Production and Distribution An Economic Concept: “The Small Budget Film,” Was it Myth or Reality? t has often been assumed that the New Wave provoked a sudden Ibreak in the production practices of French cinema, by favoring small budget films. In an industry characterized by an inflationary spiral of ever-increasing production costs, this phenomenon is sufficiently original to warrant investigation. Did most of the films considered to be part of this movement correspond to this notion of a small budget? We would first have to ask: what, in 1959, was a “small budget” movie? The average cost of a film increased from roughly $218,000 in 1955 to $300,000 in 1959. That year, at the moment of the emergence of the New Wave, 133 French films were produced; of these, 33 cost more than $400,000 and 74 cost more than $200,000. That leaves 26 films with a budget of less than $200,000, or “low budget productions;” however, that can hardly be used as an adequate criterion for movies to qualify as “New Wave.”1 Even so, this budgetary trait has often been employed to establish a genealogy for the movement. It involves, primarily, “marginal” films produced outside the dominant commercial system. Two Small Budget Films, “Outside the System” From the point of view of their mode of production, two titles are often imposed as reference points: Jean-Pierre Melville’s self-produced Silence of 49 A Mode of Production and Distribution the Sea, 1947, and Agnes Varda’s La Pointe courte (Short Point), made seven years later, in 1954. -

François Truffaut's Jules and Jim and the French New Wave, Re-Viewed

FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. 29, núms. 1-2 (2019) · ISSN: 2014-668X François Truffaut’s Jules and Jim and the French New Wave, Re-viewed ROBERT J. CARDULLO University of Michigan Abstract Truffaut’s early protagonists, like many of those produced by the New Wave, were rebels or misfits who felt stifled by conventional social definitions. His early cinematic style was as anxious to rip chords as his characters were. Unlike Godard, Truffaut went on in his career to commit himself, not to continued experiment in film form or radical critique of visual imagery, but to formal themes like art and life, film and fiction, and art and education. This article reconsiders a film that embodies such themes, in addition to featuring characters who feel stifled by conventional social definitions: Jules and Jim. Keywords: François Truffaut; French film; New Wave; Jules and Jim; Henri- Pierre Roché Resumen Los primeros protagonistas de Truffaut, como muchos de los producidos por la New Wave, eran rebeldes o inadaptados que se sentían agobiados por las convenciones sociales convencionales. Su estilo cinematográfico temprano estaba tan ansioso por romper moldes como sus personajes. A diferencia de Godard, Truffaut continuó en su carrera comprometiéndose, no a seguir experimentando en forma de película o crítica radical de las imágenes visuales, sino a temas formales como el arte y la vida, el cine y la ficción, y el arte y la educación. Este artículo reconsidera una película que encarna dichos temas, además de presentar personajes que se sienten ahogados: Jules y Jim. Palabras clave: François Truffaut, cine francés, New Wave; Jules and Jim, Henri-Pierre Roché. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

1 Evolving Authorship, Developing Contexts: 'Life Lessons'

Notes 1 Evolving Authorship, Developing Contexts: ‘Life Lessons’ 1. This trajectory finds its seminal outlining in Caughie (1981a), being variously replicated in, for example, Lapsley and Westlake (1988: 105–28), Stoddart (1995), Crofts (1998), Gerstner (2003), Staiger (2003) and Wexman (2003). 2. Compare the oft-quoted words of Sarris: ‘The art of the cinema … is not so much what as how …. Auteur criticism is a reaction against sociological criticism that enthroned the what against the how …. The whole point of a meaningful style is that it unifies the what and the how into a personal state- ment’ (1968: 36). 3. For a fuller discussion of the conception of film authorship here described, see Grist (2000: 1–9). 4. While for this book New Hollywood Cinema properly refers only to this phase of filmmaking, the term has been used by some to designate ‘either something diametrically opposed to’ such filmmaking, ‘or some- thing inclusive of but much larger than it’ (Smith, M. 1998: 11). For the most influential alternative position regarding what he calls ‘the New Hollywood’, see Schatz (1993). For further discussion of the debates sur- rounding New Hollywood Cinema, see Kramer (1998), King (2002), Neale (2006) and King (2007). 5. ‘Star image’ is a concept coined by Richard Dyer in relation to film stars, but it can be extended to other filmmaking personnel. To wit: ‘A star image is made out of media texts that can be grouped together as promotion, publicity, films and commentaries/criticism’ (1979: 68). 6. See, for example, Grant (2000), or the conception of ‘post-auteurism’ out- lined and critically demonstrated in Verhoeven (2009). -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß. -

Fall 2001 Page 1 of 7

Screen/Society Fall 2001 Page 1 of 7 Screen/Society Fall 2001 Schedule Update 11/12: The Richard White Auditorium will not be 35mm-ready until after the Fall Semester. In order to accomodate 35mm, some screening dates and locations have been changed. Please check this website regularly for updates. All 35mm film programming will be held in Griffith. Screen/Society was started in 1991 by graduate students in English and the Graduate Program in Literature working with staff in the Program in Film and Video. It has continued to provide challenging programming for the Duke community, emphasizing the importance of screening work in its original format, whether video, 16mm or 35mm. Our goal is to advance the academic study of film at Duke and to work with Arts and Sciences Departments to find ways to relate film, video, and digital art to studies in other disciplines. Screen/Society encompasses the following components: z Public Exhibition ? department-, center- and program-curated film series z Southern Circuit ? touring series organized by the South Carolina Arts Commission featuring new works and the artists in person z North Carolina Latin American Film Festival ? touring series presented at state schools and universities z Cinemateque ? Arts and Sciences course-related film screenings Films will be screened at 8pm in the Richard White Auditorium on Duke University?s East Campus, unless otherwise noted. Please check schedule for screening dates. All films are free to the general public unless otherwise noted. Public Exhibition provides an opportunity for departments, programs, and centers to curate film series. These series may be related to courses, research or broad themes of interest.