Puzeyetal2021njsosignalsofo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swedish Dimensional Adjectives

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Studies in Scandinavian Philology NEW SERIES ——————————————– 36 ——————————————– Swedish Dimensional Adjectives Anna Vogel Almqvist & Wiksell International Stockholm – Sweden ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Studies in Scandinavian Philology NEW SERIES ——————————————– 36 ——————————————– Swedish Dimensional Adjectives Anna Vogel Illustrations by Agnes Stenqvist Almqvist & Wiksell International Stockholm – Sweden Doctoral dissertation 2004 Department of Scandinavian Languages Stockholm University SE-106 91 STOCKHOLM Abstract Vogel, Anna. 2004. Swedish Dimensional Adjectives. (Svenska dimensionsadjektiv.) Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis. Stockholm Studies in Scandinavian Philology. New Series. 36. Almqvist & Wiksell International. 377 pp. The purpose of this study is to give a thorough and detailed account and analysis of the semantics of twelve Swedish dimensional adjectives: hög ‘high/tall’, låg ‘low’, bred ‘broad/wide’, smal ‘narrow/thin’, vid ‘broad’, trång ‘narrow’, tjock ‘thick’, tunn ‘thin’, djup ‘deep’, grund ‘narrow’, lång ‘long’ and kort ‘short’. Focus has been placed on their spatial, non-metaphorical sense. The study was written within the framework of cognitive linguistics, where lexical definitions may be given in terms of prototypical and peripheral uses. Four sources of data have been considered: a corpus, consisting of contemporary fiction, an elicitation test, designed for the purpose, dictionary articles on the pertinent adjectives, and the author’s own linguistic intuition as a native speaker. The methodology has involved categorisation of combinations of adjective and noun, based upon three major themes: orientation, function, and shape. In order to determine prototypical uses, precedence has been given to the outcome of the elicitation test over the corpus search. For both sources, frequency has played an important part. The ranking of senses as stated in the dictionary articles has also been considered. -

Hotel Bayarena Leverkusen

HOTEL BAYARENA Leverkusen NICHT NUR BESSER. ANDERS. LOGENPLAtz – FÜR BUSINESS UND SPORT. Eingebettet in die Nordkurve des Stadions vom Bundesligisten Bayer 04 Leverkusen ist das Lindner Hotel BayArena nicht nur Deutschlands erstes Stadionhotel, sondern auch DIE Location für Business Traveller, Städtebummler & Fußballfans in Leverkusen! Modern gemütliches Design in allen Zimmern und Suiten und die Sportsbar in der 6-geschossigen Atrium Eventhalle sorgen für (ent)spannende Aufenthalte. First Class Stadion Logen und ein- zigartige Konferenz- & Veranstaltungsflächen mit sensationellem Blick ins Stadion, ausgestattet mit modernster Konferenz- und Medientechnik, garantieren einmalige Events. Das Lindner Hotel BayArena ist für jeden Anlass und in jeder Beziehung Ihr Logen- platz für Business und Sport! BOX SEAT – FOR BUSINESS AND SPORTS. Built into the north stand of the home stadium of the Bayer 04 Leverkusen national league football team, the Lindner Hotel BayArena is not only Germany‘s first stadium hotel but also THE place in Leverkusen for business travelers, visitors to the city and football fans to be. The contemporarily cozy design of all the rooms and suites and the sports bar in the 6-story atrium event hall extend the promise of a relaxing yet exciting stay. First-class stadium boxes and unique conference and event areas with a sensational view into the stadium and equipped with state-of-the-art conferencing and media technology serve as a guarantee for one-of-a-kind events. The Lindner Hotel BayArena is in every respect your „box seat“ for any occasion, be it business or sports related. ZIMMER 121 modern gestaltete Zimmer, davon 12 großzügige Studios. Alle mit individuell regelbarer Klimaanlage und kleinem Arbeits- bereich, ISDN-Telefon mit Voice-Mailbox, Telefax-, Modem- und Internetanschluss, WLAN-Internettechnik. -

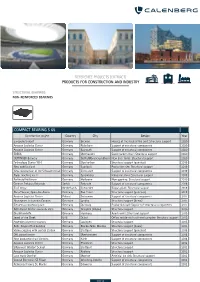

Reference List Construction and Industry

REFERENCE PROJECTS (EXTRACT) PRODUCTS FOR CONSTRUCTION AND INDUSTRY STRUCTURAL BEARINGS NON-REINFORCED BEARINGS COMPACT BEARING S 65 Construction project Country City Design Year Europahafenkopf Germany Bremen Houses at the head of the port: Structural support 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Paderborn Support of structural components 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Bayreuth Support of structural components 2020 EDEKA Germany Oberhausen Supermarket chain: Structural support 2020 OETTINGER Brewery Germany Gotha/Mönchengladbach New beer tanks: Structural support 2020 Technology Center YG-1 Germany Oberkochen Structural support (punctual) 2019 New nobilia plant Germany Saarlouis Production site: Structural support 2019 New construction of the Schwaketenbad Germany Constance Support of structural components 2019 Paper machine no. 2 Germany Spremberg Industrial plant: Structural support 2019 Parkhotel Heilbronn Germany Heilbronn New opening: Structural support 2019 German Embassy Belgrade Serbia Belgrade Support of structural components 2018 Bio Energy Netherlands Coevorden Biogas plant: Structural support 2018 NaturTheater, Open-Air-Arena Germany Bad Elster Structural support (punctual) 2018 Amazon Logistics Center Poland Sosnowiec Support of structural components 2017 Novozymes Innovation Campus Denmark Lyngby Structural support (linear) 2017 Siemens compressor plant Germany Duisburg Production hall: Support of structural components 2017 DAV Alpine Centre swoboda alpin Germany Kempten (Allgäu) Structural support 2016 Glasbläserhöfe -

Trykk Her for Å Lese Trøndernytt Nr 3/2014

TrønderNytt Medlemsblad for Norges Handikapforbund Trøndelag, Sør- og Nord-Trøndelag 03/14 14. årgang TrøndernyTT 3/2014 1 Arve H. Nordahl Leder NHF Trøndelag Trøndernytt RegionNytt har skiftet navn til TrønderNytt og fått nytt for- mat. Bakgrunnen til at vi forsøker oss med et nytt format, Leder Arve H. Nordahl er store besparelser på porto og trykking. Likevel håper og [email protected] tror vi at bladet fortsatt er like nyttig og interessant. Nestleder Sangen – Summer of ’69 av møte 18. september og 6. novem- Frode Hermansen Bryan Adams, ønsker jeg å foran- ber. I tillegg er det og planlagt fel- [email protected] dre tittel på. For etter årets som- lessamling med NHF Innlandet Steinar Mikalsen mer i Trøndelag, bør sangen 14./16. november, en samling som [email protected] heretter få navnet – Summer of er litt nyskapende og derfor meget 2014 :) spennende å få gjennomført. Birgith Berg Maken til sommer som vi alle har Temaer som det fortsatt skal jobb- [email protected] hatt denne sommeren, finnes vel bes med i NHF lokalt, regionalt Laila Bakke nesten ikke. For min del har vi og sentralt er fortsatt saker som ; [email protected] feriert i Vikna, Trøndelag, Østlan- økonomi, universell utforming, det og utrolig men sant – syden i mere informasjon og oppfølgning Anita Bråten varmen, nærmere bestemt på av BPA, Husbanken og Hjelpe- [email protected] vakre Korfu. Håper at også Dere middelformidling. Kirsti Stenersen alle sammen har hatt en like flott For meg lokalt i sommer, har jeg [email protected] sommer som meg. fortsatt jobbet med å få tilrette- Sommer betyr og at vi skal lade legge trygg skole vei for en døv/ Varamedlemmer: batterier for høsten som kommer blind skole elev – som nå i høst Øystein Forr sigende, selv om vi nå i september begynte i 7. -

Cardiff City Football Club

AWAY FAN GUIDE 2015/16 Welcome to Cardiff City Football Club The Cardiff City away fan guide has been designed to help you get the most out of your visit here at Cardiff City Stadium. This guide contains all the information you need to know about having a great away day here with us, including directions, match day activities, where to park and much more. At Cardiff City Stadium we accommodate all supporters, of all ages, with a large number of activities for everyone. Our aim is to ensure each fan has an enjoyable match-day experience regardless of the result. Cardiff City Football Club would like to thank you for purchasing your tickets; we look forward to welcoming you to Cardiff City Stadium, and wish you a safe journey to and from the venue. We are always looking at ways in which we can improve your experience here with us - so much so, that we were the first club to set up an official Twitter account and e-mail address specifically for away fans to give feedback. So, if you have any comments or questions please do not hesitate to contact us at: @CardiffCityAway or [email protected] AWAY FAN GUIDE 2015/16 How to get to the Stadium by Car If you’re traveling to the Stadium by car, access to us from the M4 is easy. Leave the M4 at junction 33 and take the A4232 towards Cardiff/Barry. Exit the A4232 on to the B4267 turn- off, signposted towards Cardiff City Stadium. Follow the slip-road off the B4267 and take the second available exit off the roundabout on to Cars Hadfield Road, and then take the third left in to Bessemer Road. -

Peace Angel of Helsinki” Wanted to Save the World

The “Peace Angel of Helsinki” wanted to save the world By Volker Kluge Unauthorised intruder at the ceremony: 23-year-old Barbara Rotraut Pleyer took her place in Olympic history with her ‘illegal’ lap of the stadium as the ‘’Peace Angel of Helsinki’’. Photo: Suomen Urheilumuseo On the 19th July 1952, the weather gods proved ungracious opening formula – for the first time in four languages. as a storm raged over Helsinki. The downpour continued Six thousand doves flew away into the grey sky, startled for hours. Yet people still streamed towards the by the 21 gun salute which accompanied the raising of stadium, protected by umbrellas and capes. Once there, the Olympic Flag. they found 70,000 wet seats. Gusts of wind made them The last torchbearer who entered the stadium was shiver. Yet they remained good-humoured, for this was nine time Olympic champion Paavo Nurmi. He kindled the opening of an Olympics for which Finland had been the bowl in the centre field. Shortly afterwards, another forced to wait twelve years. running legend Hannes Kolehmainen lit the fire at the The rain had relented by the time fanfares announced top of the stadium tower. A choir sang the Olympic hymn the ceremony at one o’clock on the dot. In those days by Jaakko Linjama. the ceremonial was still somewhat ponderous but this This solemn moment was to be followed by a sermon time at least, the IOC Members did not wear top hat and by Archbishop Ilmari Salomies. Instead, there was an tails when they were presented to Finland’s President unexpected incident. -

Cardiff-City-Stadium-Away-Fans-2018

Visiting Fan Guide 2018-2020 Croeso i Gymru. Welcome to Wales. Welcome to Cardiff, the capital city of Wales. This guide has been compiled in conjunction with the FAW and FSF Cymru, who organise Fan Embassies. The purpose is to help you get the most out of your visit to Wales. The guide is aimed to be fan friendly and contain all the information you’ll need to have an enjoyable day at the Cardiff City stadium, including directions, where to park and so much more. At the Cardiff stadium we accommodate supporters of all gender, age or nationality. Our aim is to ensure that each fan has an enjoyable matchday experience-irrespective of the result. The FAW thank you for purchasing tickets and look forward to If you have any queries, please contact us. greeting you in Cardiff, where members of the FSF Cymru fan Twitter @FSFwalesfanemb embassy team will be available to assist you around the stadium. Email [email protected] How to get to the Stadium by car If you are travelling to the stadium by We have an away parking area located in that obstructs footways and/or private car, access from the motorway is easy. the away compound of CCS (accessible entrances. Cardiff Council enforcement Leave the M4 at junction 33 and take up until 30 minutes prior to kick-off), officers and South Wales Police officers the A4232 towards Cardiff/Barry. Exit which can be accessed via Sloper Road work event days and will check that all the A4232 on to the B4267 turnoff, (next to the HSS Hire Shop). -

Norges Skøyteforbund Årbok 2015–2017

Norges Skøyteforbund Årbok 2015–2017 Versjon 2 – 30.05.2017 ©Norges Skøyteforbund 2017 Redaktør: Halvor Lauvstad Historikk/resultater: Svenn Erik Ødegård Trond Eng Bjørg Ellen Ringdal Tilrettelegging: Halvor Lauvstad Distribusjon: Elektronisk (PDF) Innholdsfortegnelse Norges Skøyteforbunds Årbok 2015-2017 2/150 Innkalling til ordinært ting for Norges Skøyteforbund Det innkalles herved til Forbundsting på Quality Hotel Edvard Grieg (Sandsliåsen 50, 5254 Bergen) på Sandsli like utenfor Bergen, 9. – 11. juni 2017. Tingforhandlingene starter fredag 9. juni kl. 16.30. Forslag og saker som ønskes behandlet på Skøytetinget 2017, må være begrunnet og innsendt gjennom et lag eller en krets til forbundsstyret innen 9 mai 2017. Minimumskrav for at for at saker/lovforslag skal bli behandlet ifb med NSFs Ting, er at innmeldte saker/forslag inneholder henvisninger til aktuelle lover/regler og konkrete forslag til endret tekst/ordlyd. NSFs lover er her: https://skoyte.klubb.nif.no/dokumentarkiv/Documents/NSF%20lov%20revidert%20NIFs%20lovnorm %20Mai%202017.pdf Forslag/saker sendes elektronisk til Norges Skøyteforbund på epost: [email protected] Skøytetinget 2017 avholdes i henhold til § 14, 15, 16, 17 og 18 i Norges Skøyteforbunds lov. Dagsorden 1. Tingets åpning a) Minnetaler b) Åpningstale c) Hilsningstaler 2. Konstituering a) Godkjenning av innkalling til Tinget b) Godkjenning av fullmaktene c) Godkjenning av dagsorden d) Godkjenning av forretningsorden e) Valg av: - 2 dirigenter - sekretærer - 2 tillitsvalgte til å undertegne protokollen - reisefordelingskomité - tellekorps - Valg av redaksjonskomite på 3 medlemmer 3. Beretninger 4. Regnskap Norges Skøyteforbunds Årbok 2015-2017 3/150 a) Regnskap for perioden 1.1.2015 til 31.12.2015 b) Regnskap for perioden 1.1.2016 til 31.12.2016 5. -

Sommerhockey Skolen 2018

Sommerhockey skolen 2018 12. – 17. August 2018 i samarbeid med Velkommen Vi har gleden av å ønske velkommen til sommerens høydepunkt, sommerhockeyskolen. Ferien nærmer seg slutten og det begynner å krible i mange unge bein. Da passer det godt å legge bort baderingene, og finne frem igjen hockeyutstyr og hockeyskøytene. Sommerhockeyskolen er Norges eldste, og startet opp allerede i 1981. Da var Hans Westberg nyansatt trener i klubben og tok med seg konseptet fra Sverige. Siden det har skolen utviklet seg videre til å bli ganske stor i landet, og mot slutten av 90- tallet var det opp til 400 deltakere fordelt på 3 uker. Mange varige vennskapsbånd ble knyttet i løpet av ukene på Hamar. Ettersom flere av de andre klubbene i landet også så muligheten med sommerhockey har antall deltakere falt noe. Vi er allikevel ganske stolt av produktet vi presenterer denne uken. For at en slik skole skal kunne fungere så godt er vi avhengig av stor grad av frivillig innsats. Vi har et arrangementsutvalg som jobber utallige timer for å få dette til. På vegen av klubben vil vi takke for den innsatsen som legges til grunne for dette. Sommerhockeyskolen er bærebjelken i klubben vår. I løpet av denne uken skal alle deltakere gjennom innholdsrikt program, bestående av bespisning, barmarkstreninger og teoriøkter. Alle treningene er ledet av kvalifiserte trenere fra egen klubb og utenom. Under sommerhockeyskolen får flere talentfulle treneraspiranter prøve seg sammen med erfarende trenere. På denne måten sørger vi for videre utvikling av klubbtrenere. Ha en flott uke alle sammen. Lykke til Med Vennlig Hilsen Monica S Bjørtomt og Marthe Camilla Wetlesen Ansvarlige Sommerhockeyskole. -

National Retailers.Xlsx

THE NATIONAL / SUNDAY NATIONAL RETAILERS Store Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Post Code M&S ABERDEEN E51 2-28 ST. NICHOLAS STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1BU WHS ST NICHOLAS E48 UNIT E5, ST. NICHOLAS CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW SAINSBURYS E55 UNIT 1 ST NICHOLAS CEN SHOPPING CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW RSMCCOLL130UNIONE53 130 UNION STREET ABERDEEN, GRAMPIAN AB10 1JJ COOP 204UNION E54 204 UNION STREET X ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY CONV E54 SOFA WORKSHOP 206 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY ALF PL E54 492-494 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1TJ TESCO DYCE EXP E44 35 VICTORIA STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1UU TESCO HOLBURN ST E54 207 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BL THISTLE NEWS E54 32 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BT J&C LYNCH E54 66 BROOMHILL ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6HT COOP GT WEST RD E46 485 GREAT WESTERN ROAD X ABERDEEN AB10 6NN TESCO GT WEST RD E46 571 GREAT WESTERN ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6PA CJ LANG ST SWITIN E53 43 ST. SWITHIN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6XL GARTHDEE STORE 19-25 RAMSAY CRESCENT GARTHDEE ABERDEEN AB10 7BL SAINSBURY PFS E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA ASDA BRIDGE OF DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA SAINSBURY G/DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA COSTCUTTER 37 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BN RS MCCOLL 17UNION E53 17 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BU ASDA ABERDEEN BEACH E55 UNIT 11 BEACH BOULEVARD RETAIL PARK LINKS ROAD, ABERDEEN AB11 5EJ M & S UNION SQUARE E51 UNION SQUARE 2&3 SOUTH TERRACE ABERDEEN AB11 5PF SUNNYS E55 36-40 MARKET STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5PL TESCO UNION ST E54 499-501 -

LET's DANCE Die Live-Tour 2019

RTL, BBC Studios, Seapoint und Semmel Concerts präsentieren: LET’S DANCE Die Live-Tour 2019 „Dancing Star 2019" Pascal Hens für Let’s Dance Live-Tour bestätigt Weitere Promis bestätigt: Ella Endlich, Benjamin Piwko und Sabrina Mockenhaupt Hamburg, 17.06.2019 – Deutschlands schönste Tanzshow begeisterte mit einem emotionalen, vielfältigen und starken Finale am vergangenen Freitag: Pascal Hens ist "Dancing Star 2019" bei RTL! Der Profi-Handballer setzte sich in einem spannenden Showdown gegen Sängerin Ella Endlich (2. Platz) und den gehörlosen Schauspieler Benjamin Piwko (3. Platz) durch und holte den Titel. Besonders erfreulich: Die drei Finalisten sowie Langstreckenläuferin Sabrina Mockenhaupt werden auch bei der Live- Tour mittanzen. Mit Oliver Pocher, der bereits vor zwei Wochen seine Teilnahme verkündete, sind aktuell fünf Stars beim großen Live-Abenteuer dabei. In den nächsten Wochen erwartet die Zuschauer noch einige Überraschungen, denn mehrere Bestätigungen stehen noch aus. Es bleibt also spannend! Das Finale sorgte für viele Überraschungen. Beim Tanzabend der großen Gefühle mussten die drei Finalisten je drei Tänze präsentieren (Jurytanz, Lieblingstanz, Freestyle). Außerdem gab es ein Wiedersehen mit den bereits ausgeschiedenen Paaren und ihren Lieblingstänzen. Und beim Sondertanz der Profitänzer tanzte Oliver Pocher unter dem Motto „Tanzen ist mein Leben" ein Medley zu „Dirty Dancing" und „Flashdance" und gab alles. Ein besonderer Gänsehautmoment war, als Sabrina Mockenhaupt mit ihrer Tour-Teilnahme überrascht wurde. Denn „Mocki“, -

Tartu Arena Tasuvusanalüüs

Tartu Arena tasuvusanalüüs Tellija: Tartu Linnavalitsuse Linnavarade osakond Koostaja: HeiVäl OÜ Tartu 2016 Copyright HeiVäl Consulting 2016 1 © HeiVäl Consulting Tartu Arena tasuvusanalüüs Uuring: Tartu linna planeeritava Arena linnahalli tasuvusanalüüs Uuringu autorid: Kaido Väljaots Geete Vabamäe Maiu Muru Uuringu teostaja: HeiVäl OÜ / HeiVäl Consulting ™ Kollane 8/10-7, 10147 Tallinn Lai 30, 51005 Tartu www.heival.ee [email protected] +372 627 6190 Uuringu tellija: Tartu Linnavalitsus, Linnavarade osakond Uuringuprojekt koostati perioodil aprill – juuli 2016. 2 © HeiVäl Consulting Tartu Arena tasuvusanalüüs Sisukord Kokkuvõte .............................................................................................................................................. 4 1 Uuringu valim .................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Tartu linn .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Euroopa .......................................................................................................................................... 11 2 Spordi- ja kultuuriürituste turuanalüüs ........................................................................................... 13 2.1 Konverentsiürituste ja messide turuanalüüs Tartus ....................................................................... 13 2.2 Kultuuriürituste turuanalüüs Tartus ...............................................................................................