John Gale – Interview Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, a MATTER of LIFE and DEATH/ STAIRWAY to HEAVEN (1946, 104 Min)

December 8 (XXXI:15) Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH/ STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN (1946, 104 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger Music by Allan Gray Cinematography by Jack Cardiff Film Edited by Reginald Mills Camera Operator...Geoffrey Unsworth David Niven…Peter Carter Kim Hunter…June Robert Coote…Bob Kathleen Byron…An Angel Richard Attenborough…An English Pilot Bonar Colleano…An American Pilot Joan Maude…Chief Recorder Marius Goring…Conductor 71 Roger Livesey…Doctor Reeves Robert Atkins…The Vicar Bob Roberts…Dr. Gaertler Hour of Glory (1949), The Red Shoes (1948), Black Narcissus Edwin Max…Dr. Mc.Ewen (1947), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), 'I Know Where I'm Betty Potter…Mrs. Tucker Going!' (1945), A Canterbury Tale (1944), The Life and Death of Abraham Sofaer…The Judge Colonel Blimp (1943), One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), 49th Raymond Massey…Abraham Farlan Parallel (1941), The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Blackout (1940), The Robert Arden…GI Playing Bottom Lion Has Wings (1939), The Edge of the World (1937), Someday Robert Beatty…US Crewman (1935), Something Always Happens (1934), C.O.D. (1932), Hotel Tommy Duggan…Patrick Aloyusius Mahoney Splendide (1932) and My Friend the King (1932). Erik…Spaniel John Longden…Narrator of introduction Emeric Pressburger (b. December 5, 1902 in Miskolc, Austria- Hungary [now Hungary] —d. February 5, 1988, age 85, in Michael Powell (b. September 30, 1905 in Kent, England—d. Saxstead, Suffolk, England) won the 1943 Oscar for Best Writing, February 19, 1990, age 84, in Gloucestershire, England) was Original Story for 49th Parallel (1941) and was nominated the nominated with Emeric Pressburger for an Oscar in 1943 for Best same year for the Best Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Writing, Original Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Missing Missing (1942) which he shared with Michael Powell and 49th (1942). -

Ronnie Barker Authorised Biography Free

FREE RONNIE BARKER AUTHORISED BIOGRAPHY PDF Bob McCabe | 272 pages | 28 Aug 2007 | Ebury Publishing | 9780563522461 | English | London, United Kingdom Ronnie Barker Authorised Biography by Bob McCabe - Penguin Books Australia Full of original contributions interviews and illustrations on one of the best-loved entertainers in showbiz. Ronnie Barker is one of the best-loved and most celebrated entertainers in British television history. As well as starring in the ever popular and Ronnie Barker Authorised Biography acclaimed sitcoms Porridge and Open All Hours, he was, of course, one of the bespectacled Two Ronnies, who topped the TV Charts for more than 15 years and are returning to our screens in spring A celebration of Ronnies life and career, published to coincide with Ronnies Ronnie Barker Authorised Biography birthday, this book contains original contributions from people who have worked with and know him best including John Cleese, David Jason who provides the forewordDavid Frost, Eric Idle, Michael Palin. Written with the full consent and collaboration of Ronnie himself, this biography is full of interviews and unseen personal illustrations from his own collection. Bob McCabe is a respected author and journalist and contributes regularly to film magazines and BBC radio arts programmes. He is the author of several books. Bob McCabe. Search books and authors. Ronnie Barker Authorised Biography. View all online retailers Find local retailers. Full Ronnie Barker Authorised Biography original contributions interviews and illustrations on one of the best-loved entertainers in showbiz Ronnie Barker is one of the best-loved and most celebrated entertainers in British television history. Also by Bob McCabe. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

Theatre for the Last Time This Season and It Could Be the Last Time Ever That He Takes Part in a Panto- 1Nime

LEEDS STUDENT NEEDS Tetley Bittennen. STAFF URGENTI,Y AT THE POLY Join em. APPLY TO TIIE EDITOR No. 75 Friday, 1st February, 1974 SECOND EDITION 3p . Union staff not· New Executive post created on I iving wage University Union Deputy President for Comm~ica tions, Jim Be,vsher, this week lashed out at the Uruon~ attitude to the payment of its staff members, some o~ whom are only receiving "It would cotst £16,925 to £13 per week. increase all their wages to His attack followed comp- 62! pence an hour, which would mean that some of lain ts from bookshop manager, Mr. Derek Perry, about the them would be receiving more low wages being received by than the permanent staff". many of the staff in the "The Union is sympathetic Union's three shops. to the permanent staff's Mr. Bewsher said, "I think claim," commented Mr. Perry, it is scandalous that in a but they aren't doing anything Union which sympathises about it. It is up to the Union . olt to agitate fc:Jc reasonable wage CK WI with so many socia 1ist m • scales for their staff from the by Nt TCHEU ions, we cannot even ensure University". that our own staff receive A new Executive post of Education and a decent living wage". "I think the Union is just Off · g e c s s fo th4 ;r Welfare icer was created at a barely quo- Although Union staff are prod ucin x u e r ~ paid by the University, they inactivity" said Mr. Bewsher, rate University Union Annual General Meet- are theoreu.cally employed by "It. -

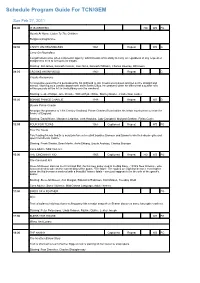

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GEM Sun Feb 27, 2011 06:00 IT IS WRITTEN HD WS PG Hearts At Home: Listen To The Children Religious programme. 06:30 CARRY ON REGARDLESS 1961 Repeat WS G Carry On Regardless Complications arise when a domestic agency, which boasts of its ability to carry on regardless of any request or assignment, tries to live up to its slogan. Starring: Sid James, Kenneth Connor, Joan Sims, Kenneth Williams, Charles Hawtrey, Bill Owen 08:25 CROOKS ANONYMOUS 1962 Repeat G Crooks Anonymous A compulsive jewel thief is persuaded by his girlfriend to join crooks anonymous and get on the straight and narrow. Working as a London department store Santa Claus, he weakens when he learns that a quarter of a million pounds will be left in the building over the weekend. Starring: Leslie Phillips, Julie Christie, Wilfred Hyde White, Stanley Baxter, J Robertson Justice 10:20 BONNIE PRINCE CHARLIE 1948 Repeat WS G Bonnie Prince Charlie Amongst the grandeur of 18th Century Scotland, Prince Charles Stuart rallies his fellow countrymen to seize the throne of England. Starring: David Niven, Margaret Leighton, Jack Hawkins, Judy Campbell, Morland Graham, Finlay Currie 12:35 FOUR FOR TEXAS 1963 Captioned Repeat WS PG Four For Texas Two feuding friends find they must join forces to outwit baddies Bronson and Buono to win their dream girls and open their dream casino. Starring: Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Anita Ekberg, Ursula Andress, Charles Bronson Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 15:00 THE CINCINNATI KID 1965 Captioned Repeat HD WS PG The Cincinnati Kid Steve McQueen stars as the Cincinnati Kid, the hot new poker stud in the Big Easy - 1930's New Orleans - who is determined to take on the current king of the game, "The Man". -

Disabling Comedy and Anti-Discrimination Legislation

Disabling Comedy and Anti-Discrimination Legislation Colin Barnes 1991 A version of this paper entitled 'Disabling Comedy' appeared in Greater Manchester Coalition of Disabled People's Journal 'Coalition' December 1991 pp. 26 - 28 Over the last couple of years disabled people and their organizations have become increasingly concerned about disabling imagery in the media. One of the most important examples being the cynical exploitation of disabled people by charities in their efforts to raise money. Here I would like to highlight another form of disablism common to the media which disabled people are expected to endure, which is equally disabling and which is often overlooked or ignored: the exploitation of disabled people by professional non-disabled comedians on television. Of course laughing at disability is not new, disabled people have been a source of amusement and ridicule for non-disabled people throughout history. Along with the other so-called timeless universals of 'popular' humour such as foreigners, women and the clergy, Elizabethan joke books are full of jokes about people with every type of impairment imaginable. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries keeping 'idiots' as objects of humour was common among those who had the money to do so, and visits to Bedlam and other 'mental' institutions were a typical form of entertainment for the able but ignorant. While such thoughtless behaviour might be expected in earlier less enlightened times, making fun of disabled people is as prevalent now as it was then. It is especially common among professional non-disabled comedians. Indeed, several of the comedy 'greats' who influenced today's 'funny' men and women built their careers around disablist humour. -

The Two Ronnies (Vintage Beeb) Free

FREE THE TWO RONNIES (VINTAGE BEEB) PDF Ronne Barker,Ronnie Barker,Ronnie Corbett | 1 pages | 04 Feb 2010 | BBC Audio, A Division Of Random House | 9781408427354 | English | London, United Kingdom The Two Ronnies (Vintage Beeb) by Ronne Barker (CD-Audio, ) for sale online | eBay Cancel anytime. Here is The Two Ronnies (Vintage Beeb) unforgettable 'Fletch', everyone's The Two Ronnies (Vintage Beeb) criminal, making the most of his enforced stay at Her Majesty's Pleasure. Never a man to shrink from a challenge, even from behind bars, Fletch could manage anything from organising a win on the horses to buying a council flat in Mayfair. Amazing his cellmates and infuriating officialdom, Fletch, the Arthur Daley of penal servitude, always comes out on top. Yes, it's hello again from them. For nearly 25 years The Two Ronnies were a TV institution, a much-loved double-act, each with his own inimitable, individual appeal. Who could forget Barker's hilarious 'pispronunciation', Corbett's witty monologues, the risque limericks, the puns, the patter, The Two Ronnies (Vintage Beeb) the parody? So enjoy another fun-filled feast of verbal fireworks. Inspired classic comedy from the The Two Ronnies (Vintage Beeb) one-offs who said goodnight but not goodbye. Welcome to Fawlty Towers, where attentive hotelier Basil Fawlty and his charming wife Sybil will attend to your every need - in your worst nightmare. With hapless waiter Manuel and long-suffering waitress Polly on hand to help, anything could happen during your stay - and probably will. Through the ages of Britain, from the 15th century to the 21st, Edmund Blackadder has meddled his way along the bloodlines, aided by his servant and sidekick, Baldrick, and hindered by an assortment of dimwitted aristocrats. -

Selectbuckingham August 2018 BUCK18

SELECTBuckingham August 2018 BUCK18 BC020FCLTD £425 £85 for 5 months Football World Cup Cover, Featuring a Highbury London N5 Postmark 21/05/02, Signed by 9 of the 1966 winning team, Jackie Charlton, Nobby Stiles, Geoff Hurst, Martin Peters, Gordon Banks, Roger Hunt, Alan Ball, Ray Wilson and George Cohen plus Jimmy Greaves. £50 for 10 months BC031C £500 DNA cover, featuring a Cambridge Postmark 25/02/03, signed by Francis Crick. BC028DS £200 £50 for 4 months Postal Museum cover, featuring a Bath Postmark 05/12/02, Signed by Museum patron and best-selling author, Terry Pratchett. £100 for 3 months BC033R £300 The Ascent of Everest cover, featuring London SW1 Postmark 29/04/03, Sir Edmund Hillary, George Lowe, Mike Westmascott, George Band & Doug Scott. BC218LTD £550 £50 for 11 months Windsor Castle 50th Anniversary of the first Queen Elizabeth II High Values, featuring a scarce Windsor Castle CDS Postmark 22/03/05. Signed by Constable and Governor of Windsor Castle, Sir Richard Johns. Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SELECT Buckingham Space BC001A £175 £25 for 7 months Space Tourism cover signed by moonwalker Alan Bean who was the fourth person to walk on the moon and made his first flight in to space on Apollo 12 at age 37 in 1969, 16/01/01 £25 for 7 months BC001A1 £175Signed by moonwalker Alan Bean, Triple postmarked. 16/01/01, Last One in Stock. BC001DL £125 £25 for 5 months Space Tourism cover signed by Don Lind an American scientist, naval officer, aviator and NASA Astronaut, 16/01/01. -

Humour Summaries HU 144U Thelast Matchmaker by Willie Daly

Humour Summaries HU 144U TheLast Matchmaker by Willie Daly In his long career as a matchmaker, Willie Daly has helped hundreds of couples find happiness. With his unique blend of intuition, quiet wisdom and a small drop of cunning, Willie reveals the secret to finding true love, and shares the story of a life spent bringing people together in love and marriage.For centuries, Irish matchmakers have performed the vital service of bringing people together. It is a mysterious art, and the very best matchmakers have an almost magical quality to them. Willie Daly, whose father and grandfather were matchmakers before him, is the most famous of them all. The path to love can be heart-warming, hilarious, and sometimes hair-raising—and Willie is the perfect guide. For those still looking for romance, he also has some hard-earned, practical advice. Rich with characters, humour, drama and—of course—Guinness, Willie Daly regales us with some of his funniest and most touching matchmaking stories. HU 149U Sporting Gaffes Volume 1 & 2 by BBC Audio HU 150U The Goon Show Volume 13 by The Goon Show This 13th collection turns the clock back to the 1950s and the series' earliest surviving recordings. The episodes included are 'Harry Secombe Tracks Lo-Hing Ding', 'Handsome Harry Hunts for The Lost Drummer', 'The Failures of Handsome Harry Secombe', 'The Mystery of the Monkey's Paw', 'The Man Who Tried to Destroy London's Monuments', 'The Ghastly Experiments of Dr Hans Eidelburger', and 'The Missing Prime Minister'. Also featured are surviving extracts from 'The Search for the Bearded Vulture' and 'The Giant Bombardon'. -

A YEAR of TOURING H ARTUR RUBINSTEIN ANTWERP, BELGIUM BRUSSELS

<; :■ ARTUR RUBINSTEIN Exclusive Management: HUROK ARTISTS, Inc. 711 Fifth Avenue, New York 22, N. Y. ARTUR RUBINSTEIN ‘THE MAN AND HIS MUSIC ENRICH THE LIVES OF PEOPLE EVERYWHERE' By HOWARD TAUBMAN Music Editor of the New York Times \ rtur Rubinstein is a complete artist because as an artist and admired as a man all over the Ahe is a whole man. It does not matter whether world. In his decades as a public performer he /—\ those who go to his concerts are ear-minded has appeared, it has been estimated, in every or eye-minded — or both. His performances are country except Tibet. He has not played in Ger a comfort to, and an enlargement of, all the many since the First World War, but that is faculties in the audience. And he has the choice because of his own choice. He felt then that the gift of being able to convey musical satisfaction Germans had forfeited a large measure of their —even exaltation—to all conditions of listeners right to be regarded as civilized, and he saw from the most highly trained experts to the most nothing in the agonized years of the Thirties and innocent of laymen. Forties which would cause him to change his mind about Germany. The reason for this is that you cannot separate Artur Rubinstein the man from Artur Rubinstein The breadth of Rubinstein's sympathies are in the musician. Man and musician are indivisible, escapable in the concert hall. He plays music of as they must be in all truly great and integrated all periods and lands, and to each he gives its due. -

The Physician at the Movies Peter E

The physician at the movies Peter E. Dans, MD Geoffrey Rush, Colin Firth (as Prince Albert/King George VI), and Helena Bonham Carter in The King’s Speech (2010). The Weinstein Company,/Photofest. The King’s Speech helphimrelaxhisvocalcordsandtogivehimconfidencein Starring Colin Firth, Geoffrey Rush, Helena Bonham Carter, anxiousmoments.Heisalsotoldtoputpebblesinhismouth Guy Pearce, and Derek Jacobi. like Demosthenes was said to have done to speak over the Directed by Tom Hooper. Rated R and PG. Running time 118 waves.Allthatdoesismakehimalmostchoketodeath. minutes. His concerned wife, Elizabeth (Helena Bonham Carter), poses as a Mrs. Johnson to enlist the aid of an unorthodox box-officefavoritewithanupliftingcoherentstorywins speechtherapist,LionelLogue,playedwithgustobyGeoffrey the Academy Award as Best Picture. Stop the presses! Rush. Firth deserved his Academy Award for his excellent AThefilm chronicles the transformation of the Duke of York job in reproducing the disability and capturing the Duke’s (ColinFirth),wholookslike“adeerintheheadlights”ashe diffidence while maintaining his awareness of being a royal. stammers and stutters before a large crowd at Wembley Still,itisRushwhomakesthemoviecomealiveandhasthe StadiumattheclosingoftheEmpireExhibitionin1925, best lines, some from Shakespeare—he apologizes to Mrs. J tohisdeliveryofaspeechthatralliesanationatwar fortheshabbinessofhisstudiowithalinefromOthellothat in1939.Thedoctorswhoattendtowhattheycall being“poorandcontentisrich,andrichenough.”Refusingto tongue-tiednessadvocatecigarettesmokingto -

Ronnie Barker: Blue Plaque

Ronnie Barker: Blue Plaque How many local historians get to celebrate the life of a comedy legend? Not many, I’d guess, but the Blue Plaque we’re unveiling today is not only a tribute to Ronnie Barker’s glittering career but also a reminder of his strong links with Oxford and Oxfordshire. Described in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography as ‘the country’s foremost comedy actor’, Ronnie Barker was admired and loved by millions of people. He was born in Bedford in 1929 and his professional stage career began in Aylesbury in 1948, but his formative years were spent in Oxford – and particularly here at 23 Church Cowley Road, the Barkers’ family home between 1935 and 1949. Later, between 1951 and 1955, Ronnie developed his career in repertory at the Oxford Playhouse before going on to achieve wider fame on the London stage and on radio and television. Ronnie – Ronald William George – Barker was the only son of Leonard Barker, a clerk working for Shell-Mex, and his wife Edith. The couple also had two daughters, Vera and Eileen. Leonard’s work brought him to Oxford in 1934 and the family lived initially in Cowley Road, moving to this new house on the Florence Park estate in 1935. Ronnie went to school at the then newly-built (and now vanished) Donnington Junior School in Cornwallis Road and won a scholarship to the City of Oxford High School for Boys in George Street in 1940. At school, Ronnie was remembered as ‘a round boy and very funny, even then’, and his nickname was Bumsy on account of his big bottom! He didn’t envisage an acting career –and there were few school productions in wartime – but he and a school friend, Mike Ford, staged one act plays for parents in local back gardens, demonstrating an interest in the theatre which was fuelled by visits to the New Theatre and the Oxford Playhouse.