Don Peebles the HARMO Y of OPPOSITES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art's Histories in Aotearoa New Zealand Jonathan Mane Wheoki

Art’s Histories in Aotearoa New Zealand Jonathan Mane Wheoki This is the text of an illustrated paper presented at ‘Art History's History in Australia and New Zealand’, a joint symposium organised by the Australian Institute of Art History in the University of Melbourne and the Australian and New Zealand Association of Art Historians (AAANZ), held on 28 – 29 August 2010. Responding to a set of questions framed around the ‘state of art history in New Zealand’, this paper reviews the ‘invention’ of a nationalist art history and argues that there can be no coherent, integrated history of art in New Zealand that does not encompass the timeframe of the cultural production of New Zealand’s indigenous Māori, or that of the Pacific nations for which the country is a regional hub, or the burgeoning cultural diversity of an emerging Asia-Pacific nation. On 10 July 2010 I participated in a panel discussion ‘on the state of New Zealand art history.’ This timely event had been initiated by Tina Barton, director of the Adam Art Gallery in the University of Victoria, Wellington, who chaired the discussion among the twelve invited panellists. The host university’s department of art history and art gallery and the University of Canterbury’s art history programme were represented, as were the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the City Gallery, Wellington, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, the Dunedin Public Art Gallery and the University of Auckland’s National Institute of Creative Arts and Industries. The University of Auckland’s department of art history1 and the University of Otago’s art history programme were unrepresented, unfortunately, but it is likely that key scholars had been targeted and were unable to attend. -

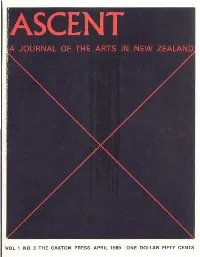

Ascent03opt.Pdf

1.1.. :1... l...\0..!ll1¢. TJJILI. VOL 1 NO 3 THE CAXTON PRESS APRIL 1909 ONE DOLLAR FIFTY CENTS Ascent A JOURNAL OF THE ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND The Caxton Press CHRISTCHURCH NEW ZEALAND EDITED BY LEO BENSEM.AN.N AND BARBARA BROOKE 3 w-r‘ 1 Published and printed by the Caxton Press 113 Victoria Street Christchurch New Zealand : April 1969 Ascent. G O N T E N TS PAUL BEADLE: SCULPTOR Gil Docking LOVE PLUS ZEROINO LIMIT Mark Young 15 AFTER THE GALLERY Mark Young 21- THE GROUP SHOW, 1968 THE PERFORMING ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND: AN EXPLOSIVE KIND OF FASHION Mervyn Cull GOVERNMENT AND THE ARTS: THE NEXT TEN YEARS AND BEYOND Fred Turnovsky 34 MUSIC AND THE FUTURE P. Plat: 42 OLIVIA SPENCER BOWER 47 JOHN PANTING 56 MULTIPLE PRINTS RITA ANGUS 61 REVIEWS THE AUCKLAND SCENE Gordon H. Brown THE WELLINGTON SCENE Robyn Ormerod THE CHRISTCHURCH SCENE Peter Young G. T. Mofi'itt THE DUNEDIN SCENE M. G. Hire-hinge NEW ZEALAND ART Charles Breech AUGUSTUS EARLE IN NEW ZEALAND Don and Judith Binney REESE-“£32 REPRODUCTIONS Paul Beadle, 5-14: Ralph Hotere, 15-21: Ian Hutson, 22, 29: W. A. Sutton, 23: G. T. Mofiifi. 23, 29: John Coley, 24: Patrick Hanly, 25, 60: R. Gopas, 26: Richard Killeen, 26: Tom Taylor, 27: Ria Bancroft, 27: Quentin MacFarlane, 28: Olivia Spencer Bower, 29, 46-55: John Panting, 56: Robert Ellis, 57: Don Binney, 58: Gordon Walters, 59: Rita Angus, 61-63: Leo Narby, 65: Graham Brett, 66: John Ritchie, 68: David Armitage. 69: Michael Smither, 70: Robert Ellis, 71: Colin MoCahon, 72: Bronwyn Taylor, 77.: Derek Mitchell, 78: Rodney Newton-Broad, ‘78: Colin Loose, ‘79: Juliet Peter, 81: Ann Verdoourt, 81: James Greig, 82: Martin Beck, 82. -

Vladamir Cacala and the Gelb House (1955) G. Elliot Reid

Vladamir Cacala and the Gelb House (1955) G. Elliot Reid Eisenman writes of a "modernism of alienation"1 which arises in the anxiety of dislocation, an architecture of "an alienated culture with no roots." "Architecture has repressed the individual consciousness in the physical envi ronment that is supposed to be the happy home. I think it is exactly in the home where the unhomely is, where the terror is alive-in the repression of the unconscious. What I am trying to suggest is that the alienated house makes us realise that we cannot only be conscious of the physical world, but rather also of our own consciousness. "2 I feel that a rootless alienated repression can be a central fact of life in New Zealand, par ticularly for the exiled immigrant, to which architecture on the whole usually chooses to 'turn a blind eye,' that architecture refuses to engage with a social disintegration and a repression, preferring instead to fragment itself, submerge itself uncritically into its own condition. 75 The Gelb House I refer to a work by such an exile, Vladimir Cacala, the Gelb House, Mount Albert (1955). Cacala's work on the whole remained committed to a small circle of influences, choosing to explore a reduced vocabulary of architectural forms. (This alien ground holds no memory, no associative value for Cacala.) The typical Cacala house comprises two enveloping walls with large expanses of glass to the north; planes pushed forward at floor and roof level in the manner of Richard Neutra (for example the Kun house, 1936, or the Davis house, 1937). -

2019 Annual Report

New Zealand Portrait Gallery Te Pūkenga Whakaata Annual Report 2019 1 Chair’s Introduction On behalf of the Trustees and Management Board of the New Zealand Portrait Gallery Te Pūkenga Whakaata, it is my pleasure to present our Annual Report for 2019. Nick Cuthell, Portrait of Dr Alan Bollard. 2012. Collection, Reserve Bank of New Zealand. This is my first report to you as Chair, We are very grateful to all the artists and I am delighted to confirm the and curators for their work in bringing Gallery is in good heart despite the these remarkable exhibitions to the financial challenges we continue to Gallery. face. We are also very grateful to our The year’s exhibition programme has sponsors for their backing of this been a resounding success – from year’s programme. Without them John Walsh’s stunning Portrait of our exhibitions would not have been Ūawa Tolaga Bay with its massive possible. Special thanks must be mural of an East Coast community given to Chris and Kathy Parkin whose to the three innovative and diverse generosity provided a professional exhibitions which followed. The publicist to promote our exhibitions. range of experience represented As a result, visitor numbers are by these exhibitions, as well as running almost 6% ahead of last year. the small exhibitions in the front Our loyal Friends and supporters have gallery, encapsulate our evolving also continued to champion projects understanding of ourselves as New to improve the Gallery’s facilities, and Zealanders, our history and creativity. the Director and her team continue to 2 Cover image: Opening of Being Chinese in Aotearoa exhibition, 20 November 2019. -

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES O achieve any depth or spread in an article attempt• ing to cover the whole gamut of New Zealand writing * must be deemed to be a New Zealand madman's dream, but I wonder if it would be so difficult for people overseas, particularly in other parts of the Commonwealth. It would appear to them, perhaps, that two or three rather good poets have emerged from these islands. So good, in fact, that their appearance in any anthology of Common• wealth poetry would make for a matter of rather pleasurable comment and would certainly not lower the general stand• ard of the book. I'll come back to these two or three poets presently, but let us first consider the question of New Zealand's prose writers. Ah yes, we have, or had, Kath• erine Mansfield, who died exactly fifty years ago. Her work is legendary — her Collected Stories (Constable) goes from reprint to reprint, and indeed, pirate printings are being shovelled off to the priting mills now that her fifty year copyright protection has run out. But Katherine Mansfield never was a "New Zealand writer" as such. She left early in the piece. But how did later writers fare, internationally speaking? It was Janet Frame who first wrote the long awaited "New Zealand Novel." Owls Do Cry was published in 1957. A rather cruel but incisive novel, about herself (everyone has one good novel in them), it centred on her own childhood experiences in Oamaru, a small town eighty miles north of Dunedin -— a town in which rough farmers drove sheep-shit-smelling American V-8 jalopies inexpertly down the main drag — where the local "bikies" as they are now called, grouped in vociferous RECENT NEW ZEALAND WRITING 17 bunches outside the corner milk bar. -

Staff Publications List

Staff Publications 1998 Published by the Research Policy Office Victoria University of Wellington PO Box 600 Wellington, New Zealand ISSN 1174-121X CONTENTS FACULTY OF COMMERCE AND ADMINISTRATION 3 Accounting and Commercial Law, School of 3 Business and Public Management, School of 5 Communications and Information Systems Management, School of 11 Economics and Finance, School of 13 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES 16 Anthropology 16 Art History 17 Asian Languages 18 Classics 19 Criminology, Institute of 20 Education, School of 22 Institute for Early Childhood Studies 24 English, Film and Theatre, School of 25 European Languages 32 History 33 Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, School of 36 Maori Studies: Te Kawa a Maui, School of 41 Music, School of 41 Nursing and Midwifery 43 Philosophy 45 Political Science and International Relations, School of 46 Sociology and Social policy 47 Women’s Studies 49 FACULTY OF LAW 51 FACULTY OF SCIENCE 54 Architecture, School of 54 Biological Sciences, School of 58 Chemical and Physical Sciences, School of 63 Earth Sciences, School of 65 Mathematical and Computing Sciences, School of 70 Psychology, School of 80 UNIVERSITY INSTITUTES AND CENTRES 82 Centre for Continuing Education/Te Whare Pukenga 82 Health Services Research Centre 83 Institute of Policy Studies 84 University Teaching Development Centre 85 Centre for Strategic Studies 85 Stout Research Centre 86 2 1998 Staff Publications FACULTY OF COMMERCE AND ADMINISTRATION ACCOUNTING AND COMMERCIAL LAW 3. Articles/Chapters/Conference Papers Articles Anderson, Gordon, ‘Interpreting the Employment Contracts Act: Are the Courts Undermining the Act?’, California Western International Law Journal, 28 (1997), pp. -

S Waistcoat and Other Duchampian Traces

Attracting Dust in New Zealand Lost And Found: Betty’s Waistcoat and Other Duchampian Traces In 1983, three works by Marcel Duchamp found their way into the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa, Wellington, New Zealand). The following account demonstrates how two New York-based friends of Duchamp, Judge Julius Isaacs, and Betty Isaacs (Fig. 1) are tied to this course of events. click to enlarge Figure 1 Betty Isaacs and Julius Isaacs, Wellington New Zealand, 1966. Copyright Fairfax NZ Ltd. Courtesy Dominion Post and Te Papa Museum Moreover this essay exposes how this process, despite the diligence of Duchamp scholarship, led to the virtual disappearance of these works from the record. This essay will also draw (preliminary) conclusions about the significance of this process, both in terms of the new light shed on the fate of Duchamp’s work, and of the reception of this work outside the centers of art practice.(1) These works are the BETTY waistcoat (1961, New York), The Box in a Valise, (Edition D. 1961, Paris) and The Chess Players (copperplate etching, artist’s proof, 1965, New York). In addition, five 1st edition publications on Marcel Duchamp signed with personal dedications accompany the works.(2) All these form part of the bequest of Judge Julius Isaacs to the National Art Gallery of New Zealand (NAG) in 1983. The Duchamp works are the most important items in a gift of over 200 artworks, publications, and articles donated to the museum by the estate of Mrs. Betty and Judge Julius Isaacs, who were New York-based friends of Marcel Duchamp. -

Russell Clark 1905-1966 Strong Reaction to Sir

THE JOURNAL OF THE CANTERBURY SOCIETY OF ARTS CNR DURHAM AND ARMAGH STREETS P.O. BOX 772 news CHRISTCHURCH NUMBER NINE, SEPTEMBER, 1966 TELEPHONE 67-261 RUSSELL CLARK 1905-1966 TOLERANCE AND INTOLERANCE Whoever was "sure members would enjoy reading the very fine speech" of Sir Charles Wheeler did not, I hope, think he was referring to all members. I did not enjoy it. Was its prominent publication in the "News", and the drooling introduction in the little rectangle at the top, a sort of student-like joke to raise a laugh? Or was it a social-climbing activity designed to seduce thoss members not critically expert enough to defend themselves mentally against this sort of manipulation by their organisers? To the first point, I did not laugh, the joke was too likely to be taken seriously by too many. To the second, my answer is that I am angry to think that my good intentions in joining the Society in the first place have landed me in the position of belonging to an organisation apparently willing to erode my standards by threatening me with the charge of intolerance if I don't tolerate this intolerable down- sucking quicksand. People who throw about spent phrases and words like "delightful", "very much pleasure", "very fine" in print can have very little to say surely, but wish to impress us rather by the dinner-jackets (jaded uniform!) their heroes wear, and the social prominence of the positions they hold. This particular piece of pomposity has latched on to the word tolerance, and used it as a weapon, In his life he displayed a never-ending capacity for hoping to disarm the opposition so plainly expected— creative endeavour. -

Publication.Pdf

1 NEWTON I, 1960–64 In 1960 McCahon and his family moved from Titirangi to the inner- city suburb of Newton, in those days a predominantly working-class and Polynesian neighbourhood. The award of the first Hay’s Art Prize to McCahon for Painting (1958), a radical abstract, caused a furore in newspapers and much unwelcome negative publicity for the artist. After a year of little painting, he embarked on the Gate series (including Here I give thanks to Mondrian, p. 10), an important new series of geometrical abstractions, exhibited at The Gallery (Symonds Street, Auckland) in 1961; a further extension of the series was the sixteen-panel The Second Gate Series (1962, pp. 51–53), a collaboration with John Caselberg (who supplied the Old Testament texts) which addressed the threat of nuclear annihilation; it was exhibited in Christchurch with other work in 1962. Lack of critical enthusiasm for this abstract/text work led McCahon to reconsider his direction, resulting in a ‘return’ (his word) to landscape painting in a large open Northland series (1962, p. 33, 59) and Landscape theme and variations (1963, pp. 60–61), two eight- panel series, exhibited at The Gallery simultaneously with a joint Woollaston/McCahon retrospective at Auckland City Art Gallery. In 1964, after twelve years at Auckland City Art Gallery, McCahon resigned to join the staff of Auckland University’s Elam School of Fine Arts, where he taught from 1964 to 1971. His first exhibition after joining Elam, Small Landscapes and Waterfalls (Ikon Fine Arts, 1964), proved to be both aesthetically and commercially successful. -

JACQUELINE FAHEY B. 1929, Timaru

GOW LANGSFORD GALLERY JACQUELINE FAHEY b. 1929, Timaru Jaqueline Fahey’s paintings collide portraiture with suburban landscapes to create riotously colourful compositions that revel in the chaos of domesticity. Married and a mother to three early in her painting career, the stifling gendered society of 1950s and 1960s New Zealand saw Fahey adopt unconventional colour, technique, and subject matter to reflect and actively challenge the status quo of the gender divide. Yet embedded in the artist’s pugnacious approach is a great level of affection for the women and relationships portrayed, evident in the careful detail bestowed on traditionally ‘female’ interests – clothing, interior textiles, bouquets- elevating the decorative female space above the austere settings more familiar to portraiture. Her distinctive painting style is recognisable for a raucous use of colour, with often haphazard use of perspectival space to force the viewer into the claustrophobia of the female experience. You can hear Fahey’s paintings. Expertly realised portraits are candid in their expressions – characters are shown mouth open, mid argument, or gazing off absentmindedly into the distance. Glimpses of TV sets, record players, and radios are combined with closely observed wine glasses, cups of tea, and bottles of gin. The clamour of crockery and conversation rings through the paintings and spills out into our space as they do into the painted gardens visible through open windows. Later bodies of work see Fahey applying her distinctive flare to urban environments and urban characters; translating domestic politics to their manifestation in the public environment. Born in Timaru in 1929, Fahey began her painting education in earnest at sixteen, at the Canterbury College School of Art, now Ilam. -

Finalised Priority Assessment List for 2010-11 for the Commonwealth Heritage List

Finalised Priority Assessment List for the Commonwealth Heritage List for 2010-2011 Assessment Name of Place Description Completion Date New South Wales Albury Post Office 570 Dean Street, on the north-east corner Dean and Kiewa Streets, Albury. 30/06/2011 Armidale Post Office 158 Beardy Street, corner Faulkner Street, Armidale. 30/06/2011 Bankstown Airport Air Traffic Control Tower Located at Bankstown Airport, Bankstown, Tower Road, comprising only the Bankstown Airport 30/06/2011 Control Tower. Botany Post Office 2 Banksia Street, corner Wilson Lane, Botany. 30/06/2011 Broken Hill Post Office 258-260 Argent Street, corner of Chloride Street, Broken Hill. 30/06/2011 Casino Post Office 102 Barker Street, Casino. 30/06/2011 Forbes Post Office 118 Lachlan Street, corner Court Street, Forbes. 30/06/2011 Glen Innes Post Office 319 Grey Street, corner Meade Street, Glen Innes. 30/06/2011 Goulburn Post Office 165 Auburn Street, Goulburn. 30/06/2011 Inverell Post Office 97-105 Otho Street, Inverell. 30/06/2011 Kempsey Post Office 3-5 Smith Street, corner Belgrave Street, Kempsey. 30/06/2011 Kiama Post Office 24 Terralong Street, corner Manning Street, Kiama. 30/06/2011 Llandilo International Transmitter Station About 600ha, Stoney Creek Road, Shanes Park, comprising the whole of Lot 1 DP447543. 30/06/2011 Macksville Post Office Cowper Street, corner River Street, Macksville. 30/06/2011 Maitland Post Office 381 High Street, corner Bourke Street, Maitland. 30/06/2011 Mudgee Post Office 80 Market Street, corner Perry Street, Mudgee. 30/06/2011 Muswellbrook Post Office 7 Bridge Street, Muswellbrook. 30/06/2011 Narrabri Post Office and former Telegraph 138-140 Maitland Street, corner Doyle Street, Narrabri. -

Spring Catalogue 2012

Spring Catalogue 2012 pierre peeters gallery 251 Parnell Road: Habitat Courtyard: Auckland: [email protected] (09)3774832 Welcome to our 2012 Spring Catalogue. Pierre Peeters Gallery presents fine examples of New Zealand paintings, works on paper and sculpture which span from the nineteenth century to the present day. For all enquiries ph (09)377 4832 or contact us at [email protected] www.ppg.net.nz Cover illustration: Len Lye, Self Portrait with Night Tree: 1947 W .S Melvin circa 1880 Wet Jacket Arm: Milford Sound Initialled Lower right ‘WSM’ Oil on opaque glass 170 x 280 mm W. S Melvin circa 1880 Lake Manapouri Initialled Lower left ‘ WSM’ Oil on opaque glass 170 x 280 mm These two works by W.S Melvin exemplify the decorative landscape painting of nineteenth century painters of the period working in New Zealand. They knowingly utilise the decorative strength of adjacent reds , soft purples and greens . Painted on what was commonly called ‘milk glass’, popular in nineteenth century applied arts, here Melvin employs this luminous medium for his deftly realised depictions of the picturesque South Island. W.S. Melvin was a nineteenth century painter who exhibited with the Otago Art Society from 1887–1913; and whose work featured in the NZ and South Seas Exhibition in Dunedin 1889–90. John Barr Clarke Hoyte (1835-1913) Coastal Inlet c.1870 Watercolour 390 x 640 mm John Barr Clarke Hoyte could produce airy, sweeping views of the picturesque, but in works like this, he combines the atmosphere and dampness of the elements of a North Island inlet, with a homely, pragmatic and altogether, endearing aspect.