Bulava Our Calling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIST of OPERATIVE ACCOUNTS for the DATE : 23/07/2021 A/C.TYPE : CA 03-Current Dep Individual

THE NEW URBAN CO-OP. BANK LTD. - RAMPUR , HEAD OFFICE LIST OF OPERATIVE ACCOUNTS FOR THE DATE : 23/07/2021 A/C.TYPE : CA 03-Current Dep Individual A/C.NO NAME BALANCE LAST OPERATE DATE FREEZE TELE NO1 TELE NO2 TELE NO3 Branch Code : 207 234 G.S. ENTERPRISES 4781.00 CR 30/09/2018 Normal 61 ST 1- L-1 Rampur - 244901 286 STEEL FABRICATORS OF INDIA 12806.25 CR 01/01/2019 Normal BAZARIYA MUULA ZARIF ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 331 WEEKLY AADI SATYA 4074.00 CR 30/09/2018 Normal DR AMBEDKAR LIBRARY ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 448 SHIV BABA ENTERPRISES 43370.00 CR 30/09/2018 Normal CL ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 492 ROYAL CONSTRUCTION 456.00 CR 04/07/2019 Normal MORADABAD ROAD ST 1- L-1 RAMPUR - 244901 563 SHAKUN CHEMICALS 895.00 CR 30/09/2018 Normal C-19 ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 565 SHAKUN MINT 9588.00 CR 30/09/2018 Normal OPP. SHIVI CINEMA ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 586 RIDDHI CLOTH HOUSE 13091.00 CR 30/09/2018 Normal PURANA GANJ ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 630 SAINT KABEER ACADEMY KANYA 3525.00 CR 06/12/2018 Normal COD FORM ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 648 SHIVA CONTRACTOR 579.90 CR 30/09/2018 Normal 52 ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 Print Date : 23/07/2021 4:10:05PM Page 1 of 1 Report Ref No : 462/2 User Code:HKS THE NEW URBAN CO-OP. BANK LTD. -

Download List of Famous Mosques in India

Famous Palaces in India Revised on 16-May-2018 ` Railways RRB Study Material (Download PDF) Mosque Location Jama Masjid (Bhilai) Bhilai, Chhattisgarh Jama Masjid Delhi Quwwatul Islam Masjid Delhi Moti Masjid (Red Fort) Delhi Quwwatul Islam Masjid Delhi Jamali Kamali Mosque and Tomb Delhi Sidi Sayyid Mosque Ahmedabad, Gujarat Sidi Bashir Mosque Ahmedabad, Gujarat Jamia Masjid Srinagar, Jammu & Kashmir Hazratbal Shrine Srinagar, Jammu & Kashmir Download Fathers of various fields in Science and Technology PDF Taj-ul-Masajid Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh Haji Ali Dargah Mumbai, Maharashtra Adhai Din Ka Jhonpra Ajmer, Rajasthan Ajmer Sharif Dargah Ajmer, Rajasthan Makkah Masjid Hyderabad, Telangana Gyanvapi Mosque Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh Moti Masjid (Agra Fort) Agra, Uttar Pradesh Nagina Masjid Agra, Uttar Pradesh (Gem Mosque or the Jewel Mosque) Jama Mosque (Fatehpur Sikri) Agra, Uttar Pradesh IBPS PO Free Mock Test 2 / 6 Railways RRB Study Material (Download PDF) Mosque Location Tomb of Salim Chishti Fatehpur Sikri, Uttar Pradesh Bara Imambara Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh Chota Imambara Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh Beemapally Mosque Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala Cheraman Juma Mosque Thrissur, Kerala Other Places of Interest Tombs/ Mausoleums Location Taj Mahal Agra, Uttar Pradesh Tomb of Mariam-uz-Zamani Sikandra, Agra, Uttar Pradesh Tomb of Adam Khan Qutub Minar, Mehrauli, Delhi Bibi Ka Maqbara (Taj of Deccan) Aurangabad, Maharashtra *Humayun’s Tomb Delhi Download Modern India History Notes PDF Tomb of I'timād-ud-Daulah Agra, Uttar Pradesh (Baby Taj) Tomb of -

Sufis in a 'Foreign' Zawiya: Moroccan Perceptions of the Tijani Pilgrimage to Fes Joel Green SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2018 Sufis in a 'Foreign' Zawiya: Moroccan Perceptions of the Tijani Pilgrimage to Fes Joel Green SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, African Studies Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Islamic Studies Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Green, Joel, "Sufis in a 'Foreign' Zawiya: Moroccan Perceptions of the Tijani Pilgrimage to Fes" (2018). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 3002. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/3002 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sufis in a ‘Foreign’ Zawiya: Moroccan Perceptions of the Tijani Pilgrimage to Fes Joel Green Elon University Religious Studies Location of Primary Study: Fes, Morocco Academic Director: Taieb Belghazi Research Mentor: Khalid Saqi Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for MOR, SIT Abroad, Fall 2018 Sufis in a ‘Foreign’Zawiya1 -

Sadiq Journal of Pakistan Studies (S JPS) Vol.1, No.1, (January-June 2021) Published by Department of Pakistan Studies, IUB, Pakistan (

Sadiq Journal of Pakistan Studies (S JPS) Vol.1, No.1, (January-June 2021) Published by Department of Pakistan Studies, IUB, Pakistan (https://journals.iub.edu.pk) Interfaith Harmony at Shrines in Pakistan: A Case Study of Baba Guru Nanak’s Dev Shrine - Kartarpur By Sara Iftikhar Research Officer Government College University, Lahore Abstract: Pakistan is a place where people belonging to different cultures and religions are residing together. The founder of Pakistan Quaid e Azam Muhmmad Ali Jinnah gifted liberty to the minorities in Pakistan and constitution of Pakistan safeguards the fundamental rights of Non-Muslims. Non-Muslim Minorities in Pakistan (Sikhs, Hindus and Christians etc.) have awarded freedom to go their religious places for practicing their religious obligations. Government of Pakistan has established Evacuee Trust Property Board under Act No. XIII of 1975 (which was promulgated on 1st July 1974) for management, control and disposal of the Evacuee Trust properties all over Pakistan. Undoubtedly, Pakistan is a Muslim majority country with multi-religious and multi-sectarian population. Though, we keep hearing about events of inter and intra religious intolerance every now and then. This research papers gives a comprehensive detail about the interfaith harmony at Shrines in Pakistan in order to prove that all the news we are getting through print media, electronic media or social media about religious intolerance in Pakistan is only one side of picture. Withal throwing light on the interfaith harmonious culture at Shrines, it aims to explore the concept of religious harmony or interfaith harmony. This paper briefly encapsulates the background of different shrines in Pakistan and the communities visiting them. -

Muslim Saints of South Asia

MUSLIM SAINTS OF SOUTH ASIA This book studies the veneration practices and rituals of the Muslim saints. It outlines the principle trends of the main Sufi orders in India, the profiles and teachings of the famous and less well-known saints, and the development of pilgrimage to their tombs in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. A detailed discussion of the interaction of the Hindu mystic tradition and Sufism shows the polarity between the rigidity of the orthodox and the flexibility of the popular Islam in South Asia. Treating the cult of saints as a universal and all pervading phenomenon embracing the life of the region in all its aspects, the analysis includes politics, social and family life, interpersonal relations, gender problems and national psyche. The author uses a multidimen- sional approach to the subject: a historical, religious and literary analysis of sources is combined with an anthropological study of the rites and rituals of the veneration of the shrines and the description of the architecture of the tombs. Anna Suvorova is Head of Department of Asian Literatures at the Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow. A recognized scholar in the field of Indo-Islamic culture and liter- ature, she frequently lectures at universities all over the world. She is the author of several books in Russian and English including The Poetics of Urdu Dastaan; The Sources of the New Indian Drama; The Quest for Theatre: the twentieth century drama in India and Pakistan; Nostalgia for Lucknow and Masnawi: a study of Urdu romance. She has also translated several books on pre-modern Urdu prose into Russian. -

Taajudin's Diary

Taajudin’s Diary Account of a Muslim author who accompanied Guru Nanak from Makkah to Baghdad By Sant Syed Prithipal Singh ne’ Mushtaq Hussain Shah (1902-1969) Edited & Translated By: Inderjit Singh Table of Contents Foreword................................................................................................. 7 When Guru Nanak Appeared on the World Scene ............................. 7 Guru Nanak’s Travel ............................................................................ 8 Guru Nanak’s Mission Was Outright Universal .................................. 9 The Book Story .................................................................................. 12 Acquaintance with Syed Prithipal Singh ....................................... 12 Discovery by Sardar Mangal Singh ................................................ 12 Professor Kulwant Singh’s Treatise ............................................... 13 Generosity of Mohinder Singh Bedi .............................................. 14 A Significant Book ............................................................................. 15 Recommendation ............................................................................. 16 Foreword - Sant Prithipal Singh ji Syed, My Father .............................. 18 ‘The Lion of the Lord took to the trade of the Fox’ – Translator’s Note .............................................................................................................. 20 About Me – Preface by Sant Syed Prithipal Singh ............................... -

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks 2019 Mamluk Architectural in Jerusalem Under Mamluk rule, Jerusalem assumed an exalted Landmarks in Jerusalem religious status and enjoyed a moment of great cultural, theological, economic, and architectural prosperity that restored its privileged status to its former glory in the Umayyad period. The special Jerusalem in Landmarks Architectural Mamluk allure of Al-Quds al-Sharif, with its sublime noble serenity and inalienable Muslim Arab identity, has enticed Muslims in general and Sufis in particular to travel there on pilgrimage, ziyarat, as has been enjoined by the Prophet Mohammad. Dowagers, princes, and sultans, benefactors and benefactresses, endowed lavishly built madares and khanqahs as institutes of teaching Islam and Sufism. Mausoleums, ribats, zawiyas, caravansaries, sabils, public baths, and covered markets congested the neighborhoods adjacent to the Noble Sanctuary. In six walks the author escorts the reader past the splendid endowments that stand witness to Jerusalem’s glorious past. Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem invites readers into places of special spiritual and aesthetic significance, in which the Prophet’s mystic Night Journey plays a key role. The Mamluk massive building campaign was first and foremost an act of religious tribute to one of Islam’s most holy cities. A Mamluk architectural trove, Jerusalem emerges as one of the most beautiful cities. Digita Depa Me di a & rt l, ment Cultur Spor fo Department for e t r Digital, Culture Media & Sport Published by Old City of Jerusalem Revitalization Program (OCJRP) – Taawon Jerusalem, P.O.Box 25204 [email protected] www.taawon.org © Taawon, 2019 Prepared by Dr. Ali Qleibo Research Dr. -

A Historical Reflection of the University of Rabe Rashidi, Iran

African Journal of History and Culture (AJHC) Vol. 3(9), pp. 140-147, December 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJHC DOI: 10.5897/AJHC11.032 ISSN 2141-6672 ©2011 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper A historical reflection of the University of Rabe Rashidi, Iran N. Behboodi 1*, A. Kiani 2, A. Heydari 2 1Department of Archaeology, University of Zabol, Zabol, Iran. 2Department of Geography and Urban Planning, University of Zabol, Zabol, Iran. Accepted 16 November, 2011 Rabe Rashidi has a large collection of academics and residents in the North West of Iran which return to Mughul patriarch periods. It was built in AH 8 century by Rashid al-Din Fadlallah in the government center of Tabriz. Based on proofs, Rashidabad city consist of two separate parts: Rabe Rashidi as one part and Rashidi city as the other part. Rube Rashidi as a castle was located in the central part of the city and it has some functions such as educational, religious and therapeutic. In order to achieve the main purpose of this paper, a reflection was made on the historical University of Rashidi city in ancient Tabriz region. Therefore, in the first stage of this paper, the physical system of Rashidi city was studied. Based on the data achieved from endowment design, a schematic assumption of Rashidi city was made. The methods applied on this research are content analysis and option idea through trial and multiple hypotheses. The analysis of the water supply system in its kind which uniquely helped to form basic fields of the city is schematic. -

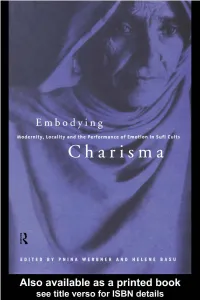

Modernity, Locality and the Performance of Emotion in Sufi Cults

EMBODYING CHARISMA Emerging often suddenly and unpredictably, living Sufi saints practising in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are today shaping and reshaping a sacred landscape. By extending new Sufi brotherhoods and focused regional cults, they embody a lived sacred reality. This collection of essays from many of the subject’s leading researchers argues that the power of Sufi ritual derives not from beliefs as a set of abstracted ideas but rather from rituals as transformative and embodied aesthetic practices and ritual processes, Sufi cults reconstitute the sacred as a concrete emotional and as a dissenting tradition, they embody politically potent postcolonial counternarrative. The book therefore challenges previous opposites, up until now used as a tool for analysis, such as magic versus religion, ritual versus mystical belief, body versus mind and syncretic practice versus Islamic orthodoxy, by highlighting the connections between Sufi cosmologies, ethical ideas and bodily ritual practices. With its wide-ranging historical analysis as well as its contemporary research, this collection of case studies is an essential addition to courses on ritual and religion in sociology, anthropology and Islamic or South Asian studies. Its ethnographically rich and vividly written narratives reveal the important contributions that the analysis of Sufism can make to a wider theory of religious movements and charismatic ritual in the context of late twentieth-century modernity and postcoloniality. Pnina Werbner is Reader in Social Anthropology at Keele University. She has published on Sufism as a transnational cult and has a growing reputation among Islamic scholars for her work on the political imaginaries of British Islam. Helene Basu teaches Social Anthropology at the Institut für Ethnologie in Berlin. -

Ghosts of the Past: the Muslim Brotherhood and Its Struggle for Legitimacy in Post‑Qaddafi Libya

Ghosts of the Past: The Muslim Brotherhood and its Struggle for Legitimacy in post‑Qaddafi Libya Inga Kristina Trauthig ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author of this paper is Inga Kristina Trauthig. She wishes to thank Emaddedin Badi for his review and invaluable comments and feedback. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own. CONTACT DETAILS For questions, queries and additional copies of this report, please contact: ICSR King’s College London Strand London WC2R 2LS United Kingdom T. +44 20 7848 2098 E. [email protected] Twitter: @icsr_centre Like all other ICSR publications, this report can be downloaded free of charge from the ICSR website at www.icsr.info. © ICSR 2018 Rxxntxxgrxxtxxng ISIS Sxxppxxrtxxrs xxn Syrxx: Effxxrts, Prxxrxxtxxs xxnd Chxxllxxngxxs Table of Contents Key Terms and Acronyms 2 Executive Summary 3 1 Introduction 5 2 The Muslim Brotherhood in Libya pre-2011 – Persecuted, Demonised and Dominated by Exile Structures 9 3 The Muslim Brotherhood’s Role During the 2011 Revolution and the Birth of its Political Party – Gaining a Foothold in the Country, Shrewd Political Manoeuvring and Punching above its Weight 15 4 The Muslim Brotherhood’s Quest for Legitimacy in the Libyan Political Sphere as the “True Bearer of Islam” 23 5 Conclusion 31 Notes and Bibliography 35 1 Key Terms and Acronyms Al-tajammu’-u al-watanī – Arabic for National Gathering or National Assembly GNA – Government of National Accord GNC – General National Council Hizb al-Adala wa’l-Tamiyya – JCP in Arabic HSC – High State Council Ikhwān – Arabic for -

Arab Scholars and Ottoman Sunnitization in the Sixteenth Century 31 Helen Pfeifer

Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750 Islamic History and Civilization Studies and Texts Editorial Board Hinrich Biesterfeldt Sebastian Günther Honorary Editor Wadad Kadi volume 177 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ihc Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750 Edited by Tijana Krstić Derin Terzioğlu LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: “The Great Abu Sa’ud [Şeyhü’l-islām Ebū’s-suʿūd Efendi] Teaching Law,” Folio from a dīvān of Maḥmūd ‘Abd-al Bāqī (1526/7–1600), The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The image is available in Open Access at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/447807 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Krstić, Tijana, editor. | Terzioğlu, Derin, 1969- editor. Title: Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750 / edited by Tijana Krstić, Derin Terzioğlu. Description: Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Islamic history and civilization. studies and texts, 0929-2403 ; 177 | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

![9Lmd\ Wxuqv ]Rr Wkurzv Eluwkgd\ Edvk](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6615/9lmd-wxuqv-rr-wkurzv-eluwkgd-edvk-1446615.webp)

9Lmd\ Wxuqv ]Rr Wkurzv Eluwkgd\ Edvk

' VRGR '%&((!1#VCEB R BP A"'!#$#1!$"#'$"#)T utqBuxyVQW 56(/5-@) -!#.+/ )*$"+, 0*%+1 $25$!82!78 !74!2 !$DE $25$!O,4!/6 !"#$% &$' 184!:#;G!5 $%5328D:/F/(!$% 1!331$285!F & &'#(%') )'#! )' ) !'#*') )' # H% >.?&: 550 &-- 7 & " *"#AB @C H! 3 ! "" ! " #$!!% , - , !"#$#%#"&# "'% %# R ! " " 27 " #$ %&'%&" ($ $@ " O P A (+,-+(.- %67284 $ " 27 &+*9- 27 t was a mix of Holi and " ,; " :+--+&;;+ Diwali in Paraunkh in " 7 ,+';; I " $ Kanpur Dehat, the native vil- +(,(/01+2 " 9+<:+9,; lage of President-elect Ram 7 =&&+ Nath Kovind on Thursday. $O". " 7 &&= Locals danced to the tune 2 ;+,&-%! "" of popular Hindi numbers, 7 +;+-'9%! applied gulal on each other and burst crackers to celebrate their " ,,<+%! / “gaon ka chhora’s” elevation to $34(,56(,+5-,6 :: + &,=< the post of President of India. 5+(3 (, %!+ " " “It is a matter of pride for us " "" " that babuji has become President 27 " 5 " of India. His victory has added " # ". sheen to our village,” said ( " . N Kovind’s nephew Sushil Kumar, $#$ "" O#3 " his face smeared with red gulal " " and hands full of laddoos. Tehsil where Kovind was born being a foregone conclusion, (2,(6,4 . The celebration was in two while in neighbouring Jhinjhak celebrations started in both " 2 #! "+ villages: Paranaukh and village his brother and other villages since Thursday 7 O Jhinjhak. Paranaukh is a non- family members reside. morning. " descript village in Derapur With Kovind’s victory Continued on Page 4 &-,: " " # " '6( * &% 23453% $ 7,00,244, while the former Lok Pranab Mukherjee. Kovind, a Sabha Speaker secured 1,844 former Bihar Governor, will be % O P rom a mud house in Kanpur votes with a value of 3,67,314.