Serbia in the Vicious Circle of Nationalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order Online

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order online Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Glossary 1. Executive Summary The 1999 Offensive The Chain of Command The War Crimes Tribunal Abuses by the KLA Role of the International Community 2. Background Introduction Brief History of the Kosovo Conflict Kosovo in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Kosovo in the 1990s The 1998 Armed Conflict Conclusion 3. Forces of the Conflict Forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Yugoslav Army Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs Paramilitaries Chain of Command and Superior Responsibility Stucture and Strategy of the KLA Appendix: Post-War Promotions of Serbian Police and Yugoslav Army Members 4. march–june 1999: An Overview The Geography of Abuses The Killings Death Toll,the Missing and Body Removal Targeted Killings Rape and Sexual Assault Forced Expulsions Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions Destruction of Civilian Property and Mosques Contamination of Water Wells Robbery and Extortion Detentions and Compulsory Labor 1 Human Shields Landmines 5. Drenica Region Izbica Rezala Poklek Staro Cikatovo The April 30 Offensive Vrbovac Stutica Baks The Cirez Mosque The Shavarina Mine Detention and Interrogation in Glogovac Detention and Compusory Labor Glogovac Town Killing of Civilians Detention and Abuse Forced Expulsion 6. Djakovica Municipality Djakovica City Phase One—March 24 to April 2 Phase Two—March 7 to March 13 The Withdrawal Meja Motives: Five Policeman Killed Perpetrators Korenica 7. Istok Municipality Dubrava Prison The Prison The NATO Bombing The Massacre The Exhumations Perpetrators 8. Lipljan Municipality Slovinje Perpetrators 9. Orahovac Municipality Pusto Selo 10. Pec Municipality Pec City The “Cleansing” Looting and Burning A Final Killing Rape Cuska Background The Killings The Attacks in Pavljan and Zahac The Perpetrators Ljubenic 11. -

Political Parties of Kosovo Serbs in the Political System of Kosovo: from Pluralism to Monism JOVANA RADOSAVLJEVIĆ & BUDIMIR NIČIĆ 3

1 NEW SOCIALINITIATIVE Political parties of Kosovo Serbs April in the political 2021 system of Kosovo: From pluralism to monism 2 Political parties of Kosovo Serbs in the political system of Kosovo: from pluralism to monism JOVANA RADOSAVLJEVIĆ & BUDIMIR NIČIĆ 3 Characteristics of the open society within Serb community in Kosovo Political Civil society parties of organizations in the Kosovo Serbs in Openness of Serbian Serbian community in the political system media in Kosovo Kosovo – Beteween of Kosovo: From perceptions and pluralism to presentation monism Attitudes of Kosovo Openness of institutions Community Rights in Serbs of security to the citizens of Kosovo Kosovo institutions Analysis of the Kosovo Serbs in the economic situation in dialogue process the Serb-populated areas in Kosovo Research title: Political parties of Kosovo Serbs in the political system of Kosovo: From pluralism to monism Published by: KFOS Prepared by: Nova društvena inicijativa (New Social Initiative) i Medija Centar (Media Center) Authors: Jovana Radosavljević, Budimir Ničić The original writing language of the analysis is Serbian language. Translated by: Biljana Simurdić Design: tedel Printed by (No. of copies): tedel (100) This paper is published within OPEN, a project carried out by the Kosovo Foundation for Open Society (KFOS) in cooperation with the organizations Nova društvena inicijativa (New Social Initiative) and Medija Centar (Media Center). Views expressed in this publication are exclusively those of the research authors and are not necessarily the views of KFOS. Year of publishing: 2021 CONTENT 05. WHO ARE 16 03. IMPORTANT PLAYERS AND POLITICAL PARTIES 9 WHAT ARE THEIR OF KOSOVO SERBS, ROLES FROM PLURALISM TO MONISM 01. -

4 VIEWS. from the Past: How I Found Myself in War?

FROM THE PAST: HOW I FOUND MYSELF IN WAR TOWARDS THE FUTURE: HOW TO REACH SUSTAINABLE PEACE 44POGLEDPOGLEDAA VLASOTINCE SPEAKERS ON THE PUBLIC FORUMS 24.10.2003. WERE PEOPLE WHO PARTICIPATED IN WARS IN THE REGION OF FORMER YUGOSLAVIA ADNAN HASANBEGOVI] IZ SARAJEVA NOVI SAD DRAGO FRAN^I[KOVI] IZ ZAGREBA 28.10.2003. GORDAN BODOG IZ ZAGREBA KEMAL BUKVI] IZ ZAGREBA KRALJEVO NERMIN KARA^I] IZ SARAJEVA 11.11.2003. NOVICA KOSTI] IZ VLASOTINCA INITIATIVE AND ORGANISATION CENTAR ZA NENASILNU AKCIJU CENTRE FOR NONVIOLENT ACTION Office in Belgrade Office in Sarajevo Studentski trg 8, 11000 Beograd, SCG Radni~ka 104, 71000 Sarajevo, BiH Tel: +381 11 637-603, 637-661 Tel: +387 33 212-919, 267-880 Fax: +381 11 637-603 Fax: +387 33 212-919 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.nenasilje.org IN COOPERATION WITH UDRU@ENJE BORACA RATA 90. VLASOTINCE DRU[TVO ZA NENASILNU AKCIJU from Novi Sad OMLADINSKA ORGANIZACIJA KVART from Kraljevo Publication edited and articles written by activists of Centre for Nonviolent Action Adnan Hasanbegovi} Helena Rill Ivana Franovi} Milan Coli} Humljan Ned`ad Horozovi} Nenad Vukosavljevi} Sanja Deankovi} Tamara [midling About the public forums, the idea and the need Should we talk about the war? us, in whose name the wars had been lead protagonists are former soldiers, ‘Whatever happened it's all water and provoked. We carry our responsibility participants of the wars taking place in the under the bridge! It's everyone's fault. The because we have either supported creat- region of former Yugoslavia during the war is evil. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Yugoslav Destruction After the Cold War

STASIS AMONG POWERS: YUGOSLAV DESTRUCTION AFTER THE COLD WAR A dissertation presented by Mladen Stevan Mrdalj to The Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of Political Science Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts December 2015 STASIS AMONG POWERS: YUGOSLAV DESTRUCTION AFTER THE COLD WAR by Mladen Stevan Mrdalj ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University December 2015 2 Abstract This research investigates the causes of Yugoslavia’s violent destruction in the 1990’s. It builds its argument on the interaction of international and domestic factors. In doing so, it details the origins of Yugoslav ideology as a fluid concept rooted in the early 19th century Croatian national movement. Tracing the evolving nationalist competition among Serbs and Croats, it demonstrates inherent contradictions of the Yugoslav project. These contradictions resulted in ethnic outbidding among Croatian nationalists and communists against the perceived Serbian hegemony. This dynamic drove the gradual erosion of Yugoslav state capacity during Cold War. The end of Cold War coincided with the height of internal Yugoslav conflict. Managing the collapse of Soviet Union and communism imposed both strategic and normative imperatives on the Western allies. These imperatives largely determined external policy toward Yugoslavia. They incentivized and inhibited domestic actors in pursuit of their goals. The result was the collapse of the country with varying degrees of violence. The findings support further research on international causes of civil wars. -

The Politicization of Ethnicity As a Prelude to Ethnopolitical Conflict: Croatia and Serbia in Former Yugoslavia

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2001 The Politicization of Ethnicity as a Prelude to Ethnopolitical Conflict: Croatia and Serbia in Former Yugoslavia Agneza Bozic-Roberson Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the International Relations Commons, Political Theory Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Bozic-Roberson, Agneza, "The Politicization of Ethnicity as a Prelude to Ethnopolitical Conflict: Croatia and Serbia in Former Yugoslavia" (2001). Dissertations. 1354. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1354 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POLITICIZATION OF ETHNICITY AS A PRELUDE TO ETHNOPOLITICAL CONFLICT: CROATIA AND SERBIA IN FORMER YUGOSLAVIA by Agneza Bozic-Roberson A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2001 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE POLITICIZATION OF ETHNICITY AS A PRELUDE TO ETHNOPOLITICAL CONFLICT: CROATIA AND SERBIA IN FORMER YUGOSLAVIA Agneza Bozic-Roberson, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2001 This interdisciplinary research develops a framework or a model for the study of the politicization of ethnicity, a process that transforms peaceful ethnic conflict into violent inter-ethnic conflict. The hypothesis investigated in this study is that the ethnopolitical conflict that led to the break up of former Yugoslavia was the result of deliberate politicization of ethnicity. -

1 Negotiating on the Brink the Domestic Side of Two-Level Games That Brought the World to the Edge of WWIII by Dania Straughan F

Negotiating on the Brink The domestic side of two-level games that brought the world to the edge of WWIII By Dania Straughan Faculty Advisor: Anthony Wanis-St. John Honors Capstone SIS Spring 2010 University Honors in SIS 1 Introduction: On June 11 th , 1999, Russian peacekeeping troops left their stations in Bosnia and entered Kosovo’s capital, taking control of the intended Kosovo Force (KFOR) headquarters, the Pristina Airport. The military maneuver, which had not been coordinated with NATO and had been denied by the Russian authorities until the news was broadcasted over CNN, blocked NATO troops from the airport and protected retreating Serbians. This little known standoff was perhaps the closest the world has been to WWIII since the Cuban Missile Crisis: NATO, Russian military, Yugoslav military and Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) forces faced each other off in a “military stew. 1” Currently no research exists analyzing the takeover of the airport and US – Russian negotiations; this paper proposes to explore the Russian decision to send troops into Kosovo through the lens of two-level games and coercive diplomacy, as well as the resulting negotiations and their effectiveness in resolving the crisis, from June 10 th through 18 th . The domestic and international context under which the Russian military contingent entered Kosovo will be evaluated through domestic public opinion polls, statements from the Duma, news articles, and the memoirs of key negotiators. Background: The Kosovo War between Serbia and NATO began in March of 1999 with several months of a NATO air bombing campaign. Russia, citing religious and historical ties to the Serbs, as well as regional interests, involved itself as a third party to the conflict. -

Serbia Guidebook 2013

SERBIA PREFACE A visit to Serbia places one in the center of the Balkans, the 20th century's tinderbox of Europe, where two wars were fought as prelude to World War I and where the last decade of the century witnessed Europe's bloodiest conflict since World War II. Serbia chose democracy in the waning days before the 21st century formally dawned and is steadily transforming an open, democratic, free-market society. Serbia offers a countryside that is beautiful and diverse. The country's infrastructure, though over-burdened, is European. The general reaction of the local population is genuinely one of welcome. The local population is warm and focused on the future; assuming their rightful place in Europe. AREA, GEOGRAPHY, AND CLIMATE Serbia is located in the central part of the Balkan Peninsula and occupies 77,474square kilometers, an area slightly smaller than South Carolina. It borders Montenegro, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina to the west, Hungary to the north, Romania and Bulgaria to the east, and Albania, Macedonia, and Kosovo to the south. Serbia's many waterway, road, rail, and telecommunications networks link Europe with Asia at a strategic intersection in southeastern Europe. Endowed with natural beauty, Serbia is rich in varied topography and climate. Three navigable rivers pass through Serbia: the Danube, Sava, and Tisa. The longest is the Danube, which flows for 588 of its 2,857-kilometer course through Serbia and meanders around the capital, Belgrade, on its way to Romania and the Black Sea. The fertile flatlands of the Panonian Plain distinguish Serbia's northern countryside, while the east flaunts dramatic limestone ranges and basins. -

Jewish Citizens of Socialist Yugoslavia: Politics of Jewish Identity in a Socialist State, 1944-1974

JEWISH CITIZENS OF SOCIALIST YUGOSLAVIA: POLITICS OF JEWISH IDENTITY IN A SOCIALIST STATE, 1944-1974 by Emil Kerenji A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Todd M. Endelman, Co-Chair Professor John V. Fine, Jr., Co-Chair Professor Zvi Y. Gitelman Professor Geoffrey H. Eley Associate Professor Brian A. Porter-Szűcs © Emil Kerenji 2008 Acknowledgments I would like to thank all those who supported me in a number of different and creative ways in the long and uncertain process of researching and writing a doctoral dissertation. First of all, I would like to thank John Fine and Todd Endelman, because of whom I came to Michigan in the first place. I thank them for their guidance and friendship. Geoff Eley, Zvi Gitelman, and Brian Porter have challenged me, each in their own ways, to push my thinking in different directions. My intellectual and academic development is equally indebted to my fellow Ph.D. students and friends I made during my life in Ann Arbor. Edin Hajdarpašić, Bhavani Raman, Olivera Jokić, Chandra Bhimull, Tijana Krstić, Natalie Rothman, Lenny Ureña, Marie Cruz, Juan Hernandez, Nita Luci, Ema Grama, Lisa Nichols, Ania Cichopek, Mary O’Reilly, Yasmeen Hanoosh, Frank Cody, Ed Murphy, Anna Mirkova are among them, not in any particular order. Doing research in the Balkans is sometimes a challenge, and many people helped me navigate the process creatively. At the Jewish Historical Museum in Belgrade, I would like to thank Milica Mihailović, Vojislava Radovanović, and Branka Džidić. -

Annual Report 2014

REPUBLIC OF SERBIA PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS 22 - 3 / 15 B e l g r a d e Ref. No. 7919 Date: 14 March 2015 REGULAR ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS FOR 2014 Belgrade, 14 March 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS: REGULAR ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS FOR 2014 ............................... 1 FOREWORD, OVERALL ASSESMENT OF RESPECT FORTHE RIGHTS OF CITIZENS AND KEY INFORMATION ON THE ACTIVITIES CARRIED OUT BY THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS in 2014 ................................................................................................................................................................... 1 KEY STATISTICS ABOUT THE WORK OF THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS ......................... 21 PART I: LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND SCOPE OF WORK OF THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS .. 25 1.1. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................ 25 1.2. COMPETENCE, SCOPE AND MANNER OF WORK ............................................................ 32 PART II: OVERVIEW BY AREAS / SECTORS ..................................................................................... 36 2.1. CHILD RIGHTS ............................................................................................................................ 36 2.2. RIGHTS OF NATIONAL MINORITIES .................................................................................... 54 2.3. GENDER EQUALITY AND RIGHTS OF LGBTI PERSONS .................................................. 70 2.4. RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES -

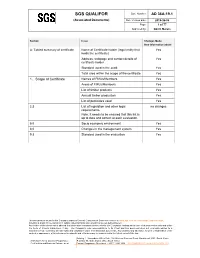

SGS QUALIFOR Doc

SGS QUALIFOR Doc. Number: AD 36A-19.1 (Associated Documents) Doc. Version date: 2019-06-06 Page: 1 of 77 Approved by: Gerrit Marais Section Issue Changes Made New Information added A: Tabled summary of certificate Name of Certificate holder (legal entity that Yes holds the certificate) Address, webpage and contact details of Yes certificate holder Standard used in the audit Yes Total area within the scope of the certificate Yes 1. Scope of Certificate Names of FMUs/Members Yes Areas of FMUs/Members Yes List of timber products Yes Annual timber production Yes List of pesticides used Yes 2.3 List of legislation and other legal no changes requirements. Note: It needs to be ensured that this list is up to date and correct at each evaluation. 5.0 Socio economic environment Yes 8.0 Changes in the management system Yes 9.3 Standard used in the evaluation Yes This document is issued by the Company under its General Conditions of Service accessible at www.sgs.com/en/Terms-and-Conditions.aspx. Attention is drawn to the limitation of liability, indemnification and jurisdiction issues defined therein. Any holder of this document is advised that information contained hereon reflects the Company’s findings at the time of its intervention only and within the limits of Client’s instructions, if any. The Company’s sole responsibility is to its Client and this document does not exonerate parties to a transaction from exercising all their rights and obligations under the transaction documents. Any unauthorized alteration, forgery or falsification of the content or appearance of this document is unlawful and offenders may be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Cinematic Representations of Nationalist-Religious Ideology in Serbian Films during the 1990s Milja Radovic Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh March 2009 THESIS DECLARATION FORM This thesis is being submitted for the degree of PhD, at the University of Edinburgh. I hereby certify that this PhD thesis is my own work and I am responsible for its contents. I confirm that this work has not previously been submitted for any other degree. This thesis is the result of my own independent research, except where stated. Other sources used are properly acknowledged. Milja Radovic March 2009, Edinburgh Abstract of the Thesis This thesis is a critical exploration of Serbian film during the 1990s and its potential to provide a critique of the regime of Slobodan Milosevic.