Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guitar Syllabus

TheThe LLeinsteinsteerr SScchoolhool ooff MusMusiicc && DDrramama Established 1904 Singing Grade Examinations Syllabus The Leinster School of Music & Drama Singing Grade Examinations Syllabus Contents The Leinster School of Music & Drama ____________________________ 2 General Information & Examination Regulations ____________________ 4 Grade 1 ____________________________________________________ 6 Grade 2 ____________________________________________________ 9 Grade 3 ____________________________________________________ 12 Grade 4 ____________________________________________________ 15 Grade 5 ____________________________________________________ 19 Grade 6 ____________________________________________________ 23 Grade 7 ____________________________________________________ 27 Grade 8 ____________________________________________________ 33 Junior & Senior Repertoire Recital Programmes ________________________ 35 Performance Certificate __________________________________________ 36 1 The Leinster School of Music & Drama Singing Grade Examinations Syllabus TheThe LeinsterLeinster SchoolSchool ofof MusicMusic && DraDrammaa Established 1904 "She beckoned to him with her finger like one preparing a certificate in pianoforte... at the Leinster School of Music." Samuel Beckett Established in 1904 The Leinster School of Music & Drama is now celebrating its centenary year. Its long-standing tradition both as a centre for learning and examining is stronger than ever. TUITION Expert individual tuition is offered in a variety of subjects: • Singing and -

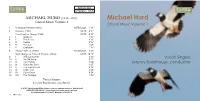

Michael Hurd

SRCD.363 STEREO DDD MICHAEL HURD (1928- 2006) Michael Hurd Choral Music Volume 1 Choral Music Volume 1 1 (1987) SATB/organ 7’54” 2 (1987) SATB 6’07” (1996) SATB 9’55” 3 I Antiphon 1’03” 4 II The Pulley 3’13” 5 III Vertue 2’47” 6 IV The Call 1’05” 7 V Exultation 1’47” 8 (1987) SATB/organ 3’00” (1994) SATB 20’14” 9 I Will you Come? 2’00” Vasari Singers 10 II An Old Song 3’12” 11 III Two Pewits 2’06” Jeremy Backhouse, conductor 12 IV Out in the Dark 3’07” 13 V The Dark Forest 2’28” 14 VI Lights Out 4’28” 15 VII Cock-Crow 0’54” 16 VIII The Trumpet 1’59” Vasari Singers Jeremy Backhouse, conductor c © 20 SRCD.363 SRCD.363 1 Michael Hurd was born in Gloucester on 19 December 1928, the son of a self- (1966) SSA/organ 11’14” employed cabinetmaker and upholsterer. His early education took place at Crypt 17 I Kyrie eleison 1’39” Grammar School in Gloucester. National Service with the Intelligence Corps involved 18 II Gloria in excelsis Deo 3’17” a posting to Vienna, where he developed a burgeoning passion for opera. He studied 19 III Sanctus 1’35” at Pembroke College, Oxford (1950-53) with Sir Thomas Armstrong and Dr Bernard 20 IV Benedictus 1’40” Rose and became President of the University Music Society. In addition, he took 21 V Agnus Dei 3’03” composition lessons from Lennox Berkeley, whose Gallic sensibility may be said to have (1980) SATB 5’39” influenced Hurd’s own musical language, not least in the attractive and witty Concerto 22 I Captivity 2’34” da Camera for oboe and small orchestra (1979), which he described in his programme 23 II Rejection 1’03” note as a homage to Poulenc’s ‘particular genius’. -

Art in Wartime

Activity: Saving Art during Wartime: A Monument Man’s Mission | Handouts Art in Wartime: Understanding the Issues At the age of 37, Walter Huchthausen left his job as a professor at the University of Minnesota and a designer and architect of public buildings to join the war efort. Several other artists, architects, and museum person- nel did the same. In December 1942, the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Francis Taylor, heard about the possibility of serving on a team of specialists to protect monuments in war zones. He wrote : “I do not know yet how the Federal Government will decide to organize this, but one thing is crystal clear; that we will be called upon for professional service, either in civilian or military capacity. I personally have ofered my services, and am ready for either.” Do you think it was a good use of U.S. resources to protect art? What kinds of arguments could be advanced for and against the creation of the MFAA? Arguments for the creation of the MFAA: Arguments against the creation of the MFAA: Walter Huchthausen lost his life trying to salvage an altarpiece in the Ruhr Valley, Germany. What do you think about the value of protecting art and architecture in comparison to the value of protecting a human life? Arguments for use of human lives to protect art during war: ABMCEDUCATION.ORG American Battle Monuments Commission | National History Day | Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media Activity: Saving Art during Wartime: A Monument Man’s Mission | Handouts Arguments against the use of human lives to protect art during war: Germany had purchased some of the panels of the famous Ghent altarpiece (above) before World War I, then removed other panels during its occupation of Belgium in World War I. -

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His Broadcasting Career Covers Both Radio and Television

557643bk VW US 16/8/05 5:02 pm Page 5 8.557643 Iain Burnside Songs of Travel (Words by Robert Louis Stevenson) 24:03 1 The Vagabond 3:24 The English Song Series • 14 DDD Iain Burnside enjoys a unique reputation as pianist and broadcaster, forged through his commitment to the song 2 Let Beauty awake 1:57 repertoire and his collaborations with leading international singers, including Dame Margaret Price, Susan Chilcott, 3 The Roadside Fire 2:17 Galina Gorchakova, Adrianne Pieczonka, Amanda Roocroft, Yvonne Kenny and Susan Bickley; David Daniels, 4 John Mark Ainsley, Mark Padmore and Bryn Terfel. He has also worked with some outstanding younger singers, Youth and Love 3:34 including Lisa Milne, Sally Matthews, Sarah Connolly; William Dazeley, Roderick Williams and Jonathan Lemalu. 5 In Dreams 2:18 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His broadcasting career covers both radio and television. He continues to present BBC Radio 3’s Voices programme, 6 The Infinite Shining Heavens 2:15 and has recently been honoured with a Sony Radio Award. His innovative programming led to highly acclaimed 7 Whither must I wander? 4:14 recordings comprising songs by Schoenberg with Sarah Connolly and Roderick Williams, Debussy with Lisa Milne 8 Songs of Travel and Susan Bickley, and Copland with Susan Chilcott. His television involvement includes the Cardiff Singer of the Bright is the ring of words 2:10 World, Leeds International Piano Competition and BBC Young Musician of the Year. He has devised concert series 9 I have trod the upward and the downward slope 1:54 The House of Life • Four poems by Fredegond Shove for a number of organizations, among them the acclaimed Century Songs for the Bath Festival and The Crucible, Sheffield, the International Song Recital Series at London’s South Bank Centre, and the Finzi Friends’ triennial The House of Life (Words by Dante Gabriel Rossetti) 26:27 festival of English Song in Ludlow. -

Nme-1952-07-18-S-Ocr

Registered at the G.P.O. as a Newspaper MUSicirAl (XE111111ESS No. 288 (NEW SERIES) EVERY FRIDAY PRICE 6d. JULY 18, 1952 Top left : US singer GuyMitchell,who arrived herethis week to open at the London Palladium, for a fortnight from Mondaynext.Top right: Mike Daniels' Band serenades Tower Bridge, in the first of the fortnightly " Rhythm on the River " trips last Sunday. Centre right: Happyopening of Ivor Kirchin's Man- hattan Club.(1. to r. seated)CabKaye, Phil Moore, Ivor Kir- chin. Standing, Jimmy Walker and Benny Lee. Bottom left: French nation- als celebrate July 14 inappropriatecos- tumeat Chelsea Town Hall.Bottom right:Luscious MarionDavis, who can be heard singing everyFridaynight withAmbrose and his Orchestra. 2 THE NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS formation to NME readers, par- ticularly in Yorkshire. The Palace Cinema,Heck- mondwike,arepresenting on Deal Sift August 1 and 2, a Republic Pic- ELL,ALL WRITE! ture which should be of great interest to jazz and pop fans tErrERs TO THE EDITOR 40 Foreign Orchestras and Musi-attempt cut everybody's throat,alike. cians.Jazz Concerts-June 28their own included. The title is "Chance of Heart"and exciting proposition to me.one way of doing it-if enough and 30. One such critic -cum -compereand features the bands of Count If the experiments come off,people joined in the Bunyard THANK you for publishing theof a well-known West End jazzBasie, Ray McKinley andthen everyone will jump on theProtest Movement, but person- statement we prepared. Ihaunt (in this case a modernFreddy Martin, with specialitiesband waggon to shout " I toldally I think the only way is for could spend a lot of time com-one)brought dawn from theby The Golden Gate Quartetyou so ". -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

The German Army, Vimy Ridge and the Elastic Defence in Depth in 1917

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 18, ISSUE 2 Studies “Lessons learned” in WWI: The German Army, Vimy Ridge and the Elastic Defence in Depth in 1917 Christian Stachelbeck The Battle of Arras in the spring of 1917 marked the beginning of the major allied offensives on the western front. The attack by the British 1st Army (Horne) and 3rd Army (Allenby) was intended to divert attention from the French main offensive under General Robert Nivelle at the Chemin des Dames (Nivelle Offensive). 1 The French commander-in-chief wanted to force the decisive breakthrough in the west. Between 9 and 12 April, the British had succeeded in penetrating the front across a width of 18 kilometres and advancing around six kilometres, while the Canadian corps (Byng), deployed for the first time in closed formation, seized the ridge near Vimy, which had been fiercely contested since late 1914.2 The success was paid for with the bloody loss of 1 On the German side, the battles at Arras between 2 April and 20 May 1917 were officially referred to as Schlacht bei Arras (Battle of Arras). In Canada, the term Battle of Vimy Ridge is commonly used for the initial phase of the battle. The seizure of Vimy ridge was a central objective of the offensive and was intended to secure the protection of the northern flank of the 3rd Army. 2 For detailed information on this, see: Jack Sheldon, The German Army on Vimy Ridge 1914-1917 (Barnsley: Pen&Sword Military, 2008), p. 8. Sheldon's book, however, is basically a largely indiscriminate succession of extensive quotes from regimental histories, diaries and force files from the Bavarian War Archive (Kriegsarchiv) in Munich. -

National Narratives of the First World War

NATIONAL NARRATIVES OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR AUTHOR(S) Aleksandra Pawliczek COLLABORATOR(S) THEMES World War I PERIOD 1914-2014 Veteran’s of Australia http://www.anzacportal.dva.gov.au/ CENDARI is funded by the European Commission’s 7th Framework Programme for Research 3 CONTENTS 6 NATIONAL NARRATIVES OF 35 THE RAPE OF BELGIUM THE FIRST WORLD WAR – MEMORY AND COMMEMORATION 38 HUNGARY’S LOST TERRITORIES Abstract Introduction 39 BIBLIOGRAPHY 8 THE “GREAT WAR” IN THE UK 12 “LA GRANDE GUERRE” IN FRANCE 16 GERMANY AND WAR GUILT 19 AUSTRIA AND THE END OF THE EMPIRE 21 ANZAC DAY IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA 25 POLAND AND THE WARS AFTER THE WAR 27 REVOLUTIONS AND CIVIL WAR IN RUSSIA 29 SERBIA’S “RED HARVEST” 31 THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE 33 UKRAINE’S FIRST ATTEMPT OF INDEPENDENCE 34 OCCUPATION OF BELARUS 4 5 National Narratives of the First World War – Memory and Commemoration CENDARI Archival Research Guide NATIONAL NARRATIVES OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR – MEMORY Here is not the place to reflect on the ambivalences of public and private memories in AND COMMEMORATION depth (but see also the ARG on Private Memories). It is rather the place to address the strongest current trends and their alteration over time, pointing at the still prevalent nar- ratives in their national contexts, which show huge differences across (European) borders Abstract and manifest themselves in the policy of cultural agents and stakeholders. According to the official memories of the First World War, cultural heritage institutions have varying How is the First World War remembered in different regions and countries? Is there a roles around the Centenary, exposing many different sources and resources on the war “European memory”, a “mémoire partagée”, or do nations and other collective groups and thus also the perceptions of the war in individual countries. -

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

Performing National Identity During the English Musical Renaissance in A

Making an English Voice: Performing National Identity during the English Musical Renaissance In a 1925 article for Music & Letters entitled ‘On the Composition of English Songs’, the British musicologist Edward J. Dent urged the ‘modern English composer’ to turn serious attention to the development of ‘a real technique of song-writing’.1 As Dent underlined, ‘song-writing affects the whole style of English musical composition’, for we English are by natural temperament singers rather than instrumentalists […] If there is an English style in music it is founded firmly on vocal principles, and, indeed, I have heard Continental observers remark that our whole system of training composers is conspicuously vocal as compared with that of other countries. The man who was born with a fiddle under his chin, so conspicuous in the music of Central and Eastern Europe, hardly exists for us. Our instinct, like that of the Italians, is to sing.2 Yet, as he quickly qualified: ‘not to sing like the Italians, for climactic conditions have given us a different type of language and apparently a different type of larynx’.3 1 I am grateful to Byron Adams, Daniel M. Grimley, Alain Frogley, and Laura Tunbridge for their comments on this research. E. J. Dent, ‘On the Composition of English Songs’, Music & Letters, 6.3 (July, 1925). 2 Dent, ‘On the Composition of English Songs’, 225. 3 Dent, ‘On the Composition of English Songs’, 225. 1 With this in mind, Dent outlined a ‘style of true English singing’ to which the English song composer might turn for his ‘primary inspiration’: a voice determined essentially by ‘the rhythms and the pace of ideal English speech – that is, of poetry’, but also, a voice that told of the instinctive ‘English temperament’. -

MUSIC School of Music Recital Hall MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY of NEWFOUNDLAND Friday, 14 April 1989 8:00P.M

THE SCHOOL OF .MUSIC School of Music Recital Hall MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NEWFOUNDLAND Friday, 14 April 1989 8:00p.m. GRADUATION RECITAL CAROLYN REID Voice ELLEN WELLS Piano The Blessed Virgin's Expostulation Henry Purcell (1659-1695) arr. Britten Ich atmet' einen linden Duft Gustav Mahler Ich binder Welt abhanden gekommen (1860-1911) Ablosung im Sommer Scheiden und Meiden Cabaret Songs Benjamin Britten Tell me the truth about love (1913-1976) Funeral Blues Johnny Calypso INTERMISSION Der Hirt auf dem F elsen Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Paula King, clarinet Les Nuits d'Ete Hector Berlioz Villanelle (1803-1869) Le Spectre de Ia Rose L 'lie inconnue Al Amor Fernando Obradors El majo celoso ( 1897 -1945) Del Cabello mas sutil Chiquitita la Novia Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Music 455B. - PROGRAMME NOTES Henry Purcell (1659-1695) The English composer Henry Purcell studied with John Blow and succeeded him as organist of Westminster Abbey in 1679. Purcell was a versatile and prolific composer; he wrote for both the theatre and the church and composed over one hundred solo songs. The Blessed Vugin's Expostulalion set to a text by Nahum Tate, alternates between recitative and arioso as the music follows the train of thought expressed by the text. The twentieth-century English composer, Benjamin Britten, has realized the piano accompaniment for a number of Purcell's songs. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) Although Gustav Mahler is best known for his large-scale orchestral works, he also wrote approximately forty songs. Between 1901 and 1904, Mahler composed ten songs with orchestral accompaniment to poems of Friedrich Ruckert including lch atmet' einen linden Duft and lch bin der Welt abhanden gelwmmen. -

Dame Joan Hammond (1912-1966) 2

AUSTRALIAN EPHEMERA COLLECTION FINDING AID DAME JOAN HILDA HOOD HAMMOND (1912-1996) PERFORMING ARTS PROGRAMS AND EPHEMERA (PROMPT) PRINTED AUSTRALIANA JULY 2018 Dame Joan Hilda Hood Hammond, DBE, CMG (24 May 1912 – 26 November 1996) was a New Zealand born Australian operatic soprano, singing coach and champion golfer. She toured widely, and became noted particularly for her Puccini roles, and appeared in the major opera houses of the world – the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, La Scala, the Vienna State Opera and the Bolshoi. Her fame in Britain came not just from her stage appearances but from her recordings. A prolific artist, Hammond's repertoire encompassed Verdi, Handel, Tchaikovsky, Massenet, Beethoven, as well as folk song, art song, and lieder. She returned to Australia for concert tours in 1946, 1949 and 1953, and starred in the second Elizabethan Theatre Trust opera season in 1957. She undertook world concert tours between 1946 and 1961. She became patron and a life member of the Victorian Opera Company (since 1976, the Victorian State Opera – VSO), and was the VSO's artistic director from 1971 until 1976 and remained on the board until 1985. Working with the then General Manager, Peter Burch, she invited the young conductor Richard Divall to become the company's Musical Director in 1972. She joined the Victorian Council of the Arts, was a member of the Australia Council for the Arts opera advisory panel, and was an Honorary Life Member of Opera Australia. She was important to the success of both the VSO and Opera Australia. Hammond embarked on a second career as a voice teacher after her performance career ended.