This Dissertation Has Been Microfilmed Exactly As Received Gubernatorial Roles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Universe of Tom

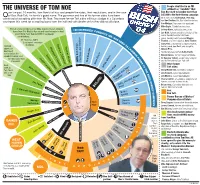

People identified in an FBI THE UNIVERSE OF TOM NOE ■ affidavit as “conduits” that ver the past 10 months, Tom Noe’s fall has cost people their jobs, their reputations, and in the case Tom Noe used to launder more than Oof Gov. Bob Taft, his family’s good name. The governor and two of his former aides have been $45,000 to the Bush-Cheney campaign: convicted of accepting gifts from Mr. Noe. Two more former Taft aides will face a judge in a Columbus MTS executives Bart Kulish, Phil Swy, courtroom this week for accepting loans from the indicted coin dealer which they did not disclose. and Joe Restivo, Mr. Noe’s brother-in-law. Sue Metzger, Noe executive assistant. Mike Boyle, Toledo businessman. Five of seven members of the Ohio Supreme Court stepped FBI-IDENTIF Jeffrey Mann, Toledo businessman. down from The Blade’s Noe records case because he had IED ‘C OND Joe Kidd, former executive director of the given them more than $20,000 in campaign UIT S’ M Lucas County board of elections. contributions. R. N Lucas County Commissioner Maggie OE Mr. Noe was Judith U Thurber, and her husband, Sam Thurber. Lanzinger’s campaign SE Terrence O’Donnell D Sally Perz, a former Ohio representative, chairman. T Learned Thomas Moyer O her husband, Joe Perz, and daughter, Maureen O’Connor L about coin A U Allison Perz. deal about N D Toledo City Councilman Betty Shultz. a year before the E Evelyn Stratton R Donna Owens, former mayor of Toledo. scandal erupted; said F Judith Lanzinger U H. -

Frontier Knowledge Basketball the Map to Ohio's High-Tech Future Must Be Carefully Drawn

Beacon Journal | 12/29/2003 | Fronti... Page 1 News | Sports | Business | Entertainment | Living | City Guide | Classifieds Shopping & Services Search Articles-last 7 days for Go Find a Job Back to Home > Beacon Journal > Wednesday, Dec 31, 2003 Find a Car Local & State Find a Home Medina Editorial Ohio Find an Apartment Portage Classifieds Ads Posted on Mon, Dec. 29, Stark 2003 Shop Nearby Summit Wayne Sports Baseball Frontier knowledge Basketball The map to Ohio's high-tech future must be carefully drawn. A report INVEST YOUR TIME Colleges WISELY Football questions directions in the Third Frontier Project High School Keep up with local business news and Business information, Market Arts & Living Although voters last month rejected floating bonds to expand the updates, and more! Health state's high-tech job development program, the Third Frontier Project Food The latest remains on track to spend more than $100 million a year over the Enjoy in business Your Home next decade. The money represents a crucial investment as Ohio news Religion weathers a painful economic transition. A new report wisely Premier emphasizes the existing money must be spent with clear and realistic Travel expectations and precise accountability. Entertainment Movies Music The report, by Cleveland-based Policy Matters Ohio, focuses only on Television the Third Frontier Action Fund, a small but long-running element of Theater the Third Frontier Project. The fund is expected to disburse $150 US & World Editorial million to companies, universities and non-profit research Voice of the People organizations. Columnists Obituaries It has been up and running since 1998, under the administration of Corrections George Voinovich. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

DETERIORATING NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE ROADS WOULD GET BOOST UNDER SENATE BILL -- March 12, 1998

For release: March 12, 1998 Janet Tennyson 202-2 19-386 1 Peter Umhofer 202-208-60 11 DETERIORATING NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE ROADS WOULD GET BOOST UNDER SENATE BILL Thousands of miles of crumbling roadways in the National Wildlife Refuge System would receive a boost under a transportation bill passedtoday by the U.S. Senate. The new funding would help remedy the $158 million road maintenance backlog faced by world’s largest network of lands dedicated to wildlife. Under the Federal Land Highways Program of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA), the reauthorization bill, S. 1173, provides for $20 million in new funding for wildlife refuge roads each year for the next 5 years. “The Senate’s action recognizes the important role the National Wildlife Refuge System plays in safeguarding America’s magnificent wildlife resources,” said Jamie Rappaport Clark, Director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the agency responsible for managing the 92-million-acre National Wildlife Refuge System. “I applaud the Senate’s efforts to addressthe maintenance needs of the National Wildlife Refuge System,” said Director Clark. “I also want to recognize the tremendous leadership of SenatorsJohn Chafee and Max Baucus in making sure the legislation addressedthese needs. Receiving this funding under the Federal Lands Highways Program would help us ensure safe and accessible roads for the 30 million Americans who visit national wildlife refuges each year. It would also allow the Fish and Wildlife Service to target limited resources toward vital wildlife conservation programs on refuges.” (over) AMERICA’S NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGES... wherewddkfe comes wzt~~dly! -2- More than 4,200 miles of public roads and 424 bridges are contained in the 5 14 wildlife refuges and 38 wetland management districts making up the National Wildlife Refuge System. -

Senator Dole FR: Kerry RE: Rob Portman Event

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu TO: Senator Dole FR: Kerry RE: Rob Portman Event *Event is a $1,000 a ticket luncheon. They are expecting an audience of about 15-20 paying guests, and 10 others--campaign staff, local VIP's, etc. *They have asked for you to speak for a few minutes on current issues like the budget, the deficit, and health care, and to take questions for a few minutes. Page 1 of 79 03 / 30 / 93 22:04 '5'561This document 2566 is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas 141002 http://dolearchives.ku.edu Rob Portman Rob Portman, 37, was born and raised in Cincinnati, in Ohio's Second Congressional District, where he lives with his wife, Jane. and their two sons, Jed, 3, and Will~ 1. He practices business law and is a partner with the Cincinnati law firm of Graydon, Head & Ritchey. Rob's second district mots run deep. His parents are Rob Portman Cincinnati area natives, and still reside and operate / ..·' I! J IT ~ • I : j their family business in the Second District. The family business his father started 32 years ago with four others is Portman Equipment Company headquartered in Blue Ash. Rob worked there growing up and continues to be very involved with the company. His mother was born and raised in Wa1Ten County, which 1s now part of the Second District. Portman first became interested in public service when he worked as a college student on the 1976 campaign of Cincinnati Congressman Bill Gradison, and later served as an intern on Crradison's staff. -

Conflicts of Interest in Bush V. Gore: Did Some Justices Vote Illegally? Richard K

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship Spring 2003 Conflicts of Interest in Bush v. Gore: Did Some Justices Vote Illegally? Richard K. Neumann Jr. Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation Richard K. Neumann Jr., Conflicts of Interest in Bush v. Gore: Did Some Justices Vote Illegally?, 16 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 375 (2003) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/153 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES Conflicts of Interest in Bush v. Gore: Did Some Justices Vote Illegally? RICHARD K. NEUMANN, JR.* On December 9, 2000, the United States Supreme Court stayed the presidential election litigation in the Florida courts and set oral argument for December 11.1 On the morning of December 12-one day after oral argument and half a day before the Supreme Court announced its decision in Bush v. Gore2-the Wall Street Journalpublished a front-page story that included the following: Chief Justice William Rehnquist, 76 years old, and Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, 70, both lifelong Republicans, have at times privately talked about retiring and would prefer that a Republican appoint their successors.... Justice O'Connor, a cancer survivor, has privately let it be known that, after 20 years on the high court,'she wants to retire to her home state of Arizona ... -

Union Calendar No. 502

1 Union Calendar No. 502 107TH CONGRESS "!REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 107–801 REPORT ON THE LEGISLATIVE AND OVERSIGHT ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS DURING THE 107TH CONGRESS JANUARY 2, 2003.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 19–006 WASHINGTON : 2003 COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS BILL THOMAS, California, Chairman PHILIP M. CRANE, Illinois CHARLES B. RANGEL, New York E. CLAY SHAW, JR., Florida FORTNEY PETE STARK, California NANCY L. JOHNSON, Connecticut ROBERT T. MATSUI, California AMO HOUGHTON, New York WILLIAM J. COYNE, Pennsylvania WALLY HERGER, California SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan JIM MCCRERY, Louisiana BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland DAVE CAMP, Michigan JIM MCDERMOTT, Washington JIM RAMSTAD, Minnesota GERALD D. KLECZKA, Wisconsin JIM NUSSLE, Iowa JOHN LEWIS, Georgia SAM JOHNSON, Texas RICHARD E. NEAL, Massachusetts JENNIFER DUNN, Washington MICHAEL R. MCNULTY, New York MAC COLLINS, Georgia WILLIAM J. JEFFERSON, Louisiana ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee PHIL ENGLISH, Pennsylvania XAVIER BECERRA, California WES WATKINS, Oklahoma KAREN L. THURMAN, Florida J.D. HAYWORTH, Arizona LLOYD DOGGETT, Texas JERRY WELLER, Illinois EARL POMEROY, North Dakota KENNY C. HULSHOF, Missouri SCOTT MCINNIS, Colorado RON LEWIS, Kentucky MARK FOLEY, Florida KEVIN BRADY, Texas PAUL RYAN, Wisconsin (II) LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS, Washington, DC, January 2, 2003. Hon. JEFF TRANDAHL, Office of the Clerk, House of Representatives, The Capitol, Washington, DC. DEAR MR. TRANDAHL: I am herewith transmitting, pursuant to House Rule XI, clause 1(d), the report of the Committee on Ways and Means on its legislative and oversight activities during the 107th Congress. -

Thirteenth Amendment A

University of Cincinnati College of Law University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications Faculty Articles and Other Publications College of Law Faculty Scholarship 2003 Stopping Time: The rP o-Slavery and 'Irrevocable' Thirteenth Amendment A. Christopher Bryant University of Cincinnati College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.uc.edu/fac_pubs Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Legal History, Theory and Process Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, A. Christopher, "Stopping Time: The rP o-Slavery and 'Irrevocable' Thirteenth Amendment" (2003). Faculty Articles and Other Publications. Paper 63. http://scholarship.law.uc.edu/fac_pubs/63 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law Faculty Scholarship at University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Articles and Other Publications by an authorized administrator of University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STOPPING TIME: THE PRO-SLAVERY AND "IRREVOCABLE" THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT • A. CHRISTOPHER BRYANT I. EXTRALEGAL AUTHORITY AND THE CREATION OF ARTICLE V ...................................... 505 II. HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF THE CORWIN AMENDMENT .......................................................... 512 III. LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF THE CORWIN AMENDMENT ......................................................... 520 A. Debate in -

Our Century 1962

THE PLAIN DEALER . SUNDAY, APRIL 11, 1999 5-D OURCENTURY 1962 ATA GLANCE Missile crisis sends Shake-up fear into every home at City Solemn Clevelanders sat glued to their tele- vision sets the evening of Oct. 22. President John F. Kennedy told them that Soviet ships were carrying missiles to Cuban missile sites Hall and the Armed Forces had orders not to let them through. As Defense Secretary Robert McNamara Celebrezze gets put it, America and the Soviets were “eyeball to eyeball.” One of the TV sets was atop the Washington job, council president’s desk at City Hall, where party brawls over council had assembled for its regular meeting. When Kennedy finished, Councilwoman Mer- his replacement cedes Cotner arose. In a quavering voice, she proposed a resolution that “we back him all By Fred McGunagle the way, even if it is with sorrow in our hearts and tears in our eyes.” It passed unanimously. On a July day, Mayor Anthony Cel- Mayor Ralph Locher quickly conferred with ebrezze was doing what he loved best Civil Defense Director John Pokorny about — cooking a fish over a campfire in the city’s preparedness for nuclear war. Canada, hundreds of miles from the problems of City Hall — when a guide • caught up with him with an urgent message: Call the White House. Wreckers were tearing down the flophouses It was a message that would shake and cheap bars that lined lower E. Ninth St. the city. John Galbreath started construction of the key John F. Kennedy told Celebrezze Erieview building, a 40-story green tower at E. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to lielp you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated vwth a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large dieet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

To the Assembled Members of the Judiciary, Dignitaries from the Other

To the assembled members of the Judiciary, dignitaries from the other branches of the government, esteemed members of the bar, and other welcomed guests, I am Judge Ronald Adrine, and it is my honor to currently serve as the Administrative and Presiding Judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court. On behalf of my colleagues and the hard-working staff of our court I bring you greetings. Before starting my presentation this afternoon, I take great pleasure in introducing to some and present to others the greatest Municipal Court bench in the country. I will call their names in alphabetical order and ask those of my colleagues who were able to join us today to rise and be recognized. They are: Judge Marilyn Cassidy Judge Pinky Carr Judge Michelle Earley Judge Emanuella Groves Judge Anita Laster Mays Judge Lauren Moore Judge Charles Patton Judge Raymond Pianka Judge Michael Ryan Judge Angela Stokes Judge Pauline Tarver Judge Joseph Zone The judges would also like to recognize Mr. Earle B. Turner, our Clerk of court. In addition, some of our staff have taken time from their lunch hour to participate in this event. I ask that all employees of the court’s General, Housing and Clerk Divisions who are present please stand and be recognized. 1 A wise person once said that, “If you don’t know where you’ve been, it’s hard to know where you are and impossible to know where you are going. In this, our court’s 100th year, I believe that that statement could not be truer. So, those of us who now serve on the court decided to take this time to pause and consider and honor our past, examine our present and to reflect upon our future. -

Appendix File 1958 Post-Election Study (1958.T)

app1958.txt Version 01 Codebook ------------------- CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1958 POST-ELECTION STUDY (1958.T) >> 1958 CONGRESSIONAL CANDIDATE CODE, POSITIVE REFERENCES CODED REFERENCES TO OPPONENT ONLY IN REASONS FOR VOTE. ELSEWHERE CODED REFERENCES TO OPPONENT IN OPPONENT'S CODE. CANDIDATE 00. GOOD MAN, WELL QUALIFIED FOR THE JOB. WOULD MAKE A GOOD CONGRESSMAN. R HAS HEARD GOOD THINGS ABOUT HIM. CAPABLE, HAS ABILITY 01. CANDIDATE'S RECORD AND EXPERIENCE IN POLITICS, GOVERNMENT, AS CONGRESSMAN. HAS DONE GOOD JOB, LONG SERVICE IN PUBLIC OFFICE 02. CANDIDATE'S RECORD AND EXPERIENCE OTHER THAN POLITICS OR PUBLIC OFFICE OR NA WHETHER POLITICAL 03. PERSONAL ABILITY AND ATTRIBUTES. A LEADER, DECISIVE, HARD-WORKING, INTELLIGENT, EDUCATED, ENERGETIC 04. PERSONAL ABILITY AND ATTRIBUTES. HUMBLE, SINCERE, RELIGIOUS 05. PERSONAL ABILITY AND ATTRIBUTES. MAN OF INTEGRITY. HONEST. STANDS UP FOR WHAT HE BELIEVES IN. PUBLIC SPIRITED. CONSCIENTIOUS. FAIR. INDEPENDENT, HAS PRINCIPLES 06. PERSONAL ATTRACTIVENESS. LIKE HIM AS A PERSON, LIKABLE, GOOD PERSONALITY, FRIENDLY, WARM 07. PERSONAL ATTRACTIVENESS. COMES FROM A GOOD FAMILY. LIKE HIS FAMILY, WIFE. GOOD HOME LIFE 08. AGE, NOT TOO OLD, NOT TOO YOUNG, YOUNG, OLD 09. OTHER THE MAN, THE PARTY, OR THE DISTRICT 10. CANDIDATE'S PARTY AFFILIATION. HE IS A (DEM) (REP) 11. I ALWAYS VOTE A STRAIGHT TICKET. TO SUPPORT MY PARTY 12. HE'S DIFFERENT FROM (BETTER THAN) MOST (D'S) (R'S) 13. GOOD CAMPAIGN. GOOD SPEAKER. LIKED HIS CAMPAIGN, Page 1 app1958.txt CLEAN, HONEST. VOTE-GETTER 14. HE LISTENS TO THE PEOPLE BACK HOME. HE DOES (WILL DO) WHAT THE PEOPLE WANT 15. HE MIXES WITH THE COMMON PEOPLE.