Alf Hattersley WWII Record

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Royal Cromer Golf Club Established 1888

History of Royal Cromer Golf Club established 1888 Information obtained from minute books, letters, members records, journals and periodicals. Royal Cromer Golf Club History Established 1888 Royal Cromer Golf Club owes its existence to the enthusiasm and love of the game of a Mr. Henry Broadhurst M.P., a Scot who lived at 19, Buckingham Street, The Strand, London. In the 1880's, whilst holidaying in Cromer, he recognised the potential of land to the seaward of the Lighthouse as a possible site for a Links Course. The popularity of North Norfolk at this time had been noted in the London City Press in a report dated 5th September 1886: "The public are greatly indebted to railway enterprise for the opening up of the East Coast. More bracing air and delightful sands are not to be found in any part of England. The only drawback is that the country is rather flat. This remark, however, does not apply to Cromer, which bids fair to become the most popular watering place, it being entirely free from objectionable features". The site of the proposed golf course was owned by the then Lord Suffield KCB, who kindly consented to the request of Broadhurst and some twenty other enthusiasts to rent the land. The Club was instituted in the Autumn of 1887 with Lord Suffield as President. Doubtless it was his friendship and influence with the Prince of Wales which precipitated the Prince's gracious patronage of the infant club on 25th December 1887. Thus Cromer had a Royal Golf Club even before its official opening the following January. -

'Olume XLVI Number 466 Winter 1978/79

n THE JOURNAL OF THE RNLI 'olume XLVI Number 466 Winter 1978/79 25p Functional protection with the best weather clothing in the world Functional Clothing is ideal for work or leisure and gives all weather comfort and protection. The "Airflow" Coat and Jackets are outer clothing which provide wind and waterproof warmth Our claim of true all-weather comfort in them is made possible by Functional AIR 'Airflow' a unique patented method of /£°o\ooq\ clothing construction •ooj Outer A One Foamliner is fitted within lining Coat and Jackets but a second one may Removable Foamliner fabrics of be inserted for severe cold wind and within waterproof JACKET & CONTOUR HOOD The "foam sandwich" "Airflow" the coated principle forms three layers of air garment nylon between the outer and lining fabrics, insulating and assuring warmth without weight or bulk There is not likely to be condensation unless the foam is unduly compressed FUNCTIONAL supplies the weather ROYAL NATIONAL clothing of the United Kingdom LIFE BOAT INSTITUTION Television Industry, the R.N.L.I. and leaders in constructional Letter from Assistant Superintendent (stores) and off-shore oil activity Your company's protective clothing has now been on extensive evaluation.... and I am pleased to advise that the crews of our offshore boats have found the clothing warm, comfortable and a considerable improvement. The issue.... is being extended to all of our offshore life-boats as replacements are required Please send me a copy of your COLD WEATHER JACKET SEAGOING OVERTROUSERS A body garment catalogue 20p from personal enquirers DIRECT FROM MANUFACTURER FUNCTIONAL % • •FUNCTIONAL CLOTHING ^ A^ • Dept 16 20 Chepstow Street* Manchester Ml 5JF. -

1949 OG BYENS SKIBSFART I SAMME TIDSROM Ved Ths. Arbo Høeg Ant. Andersens Trykkeri, Larvik

LARVIKS SJØMANNSFORENING 1849 – 1949 OG BYENS SKIBSFART I SAMME TIDSROM Ved Ths. Arbo Høeg Ant. Andersens Trykkeri, Larvik Innhold Larviks Sjømannsforening 5 Foreningens formenn 16 Foreningens æresmedlemmer 17 Saker som har vært behandlet 18 Mannskap og kosthold 37 Foreningens lokaler og vertskap 43 Minebøssen 50 50-års jubileet 9/2 1899 51 Damernes hilsen 57 Legater og utdelinger 58 Samarbeidet med Handelsstandsforeningen 60 Wistingmonumentet 62 Prolog ved C. Borch-Jenssen 64 Det rene flagg 65 Brand og dans 65 Larvik Sjøfartsmuseum 66 Larviks flåte 1849 - 1949 73 Damp og motor 89 Diverse skibsregnskaper 92 Skib i oplag 98 Fangsten i nord og syd 101 Skibsbygging 107 10 års fart med «Emma» 1865 - 1874 117 Glimt fra, seilskibstiden 131 Emigranttrafikken 156 Mangeartede skjebner 158 Seilasen under den annen verdenskrig 172 «Larviks Sjømannsforening 1849 - 1949» 2 Jubileumsboken Vår forening nedsatte i god tid en komité for å forberede en bok om 100- års jubileet. Medlemmer var kaptein A. Bjerkholdt-Hansen, som foreningens daværende formann, samt kaptein Narvesen og konsul Ths. Arbo Høeg. Senere trådte losoldermann H. M. Hansen inn i egenskap av foreningens nyvalgte formann, og derefter havnefogd Ole Jørgensen. Efter anmodning påtok Ths. Arbo Høeg sig å skrive boken om Larviks Sjømannsforening gjennom de 100 år, idet han dog forbeholdt sig å utvide rammen til også å gjelde byens skibsfart i samme tidsrom. Dette var komiteen enig i. - Vi håper at boken, slik som den foreligger, vil være av interesse først og fremst for Larviksfolk og utflyttede Larvikensere, men også for sjøfarts- interesserte i sin almindelighet. Larvik i 1948. Larviks Sjømannsforening. -

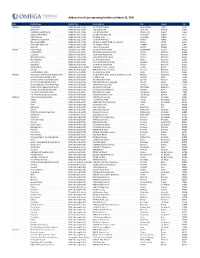

Body Name Body Service Code Service Description Expenditure Code Expenditure Category Expenditure Code Detailed Expenditure Type

Transactio n Body Expenditure Reference Name Body Service Code Service Description Expenditure Code Expenditure Category Code Detailed Expenditure Type Code Date Amount Transaction Description Customer/Supplier Name North Norfolk33UF District CouncilASSETS Assets & Leisure A Employee Costs 1000 Wages - Basic 363015 16/01/2013 930.8 REDACTED - PERSONAL INFORMATION SHAW TRUST LTD North Norfolk33UF District CouncilASSETS Assets & Leisure A Employee Costs 1000 Wages - Basic 363356 23/01/2013 744.64 REDACTED - PERSONAL INFORMATION SHAW TRUST LTD North Norfolk33UF District CouncilASSETS Assets & Leisure A Employee Costs 1224 Subs To Professional Bodies 363379 24/01/2013 595 Rics Membership Renewals RICS MEMBERSHIP RENEWALS North Norfolk33UF District CouncilASSETS Assets & Leisure B Premises 2000 R & M Bldgs - Repairs & Maint 362639 10/01/2013 645.84 Fit New Compressor BROADLAND CATERING EQUIPMENT LTD North Norfolk33UF District CouncilASSETS Assets & Leisure B Premises 2000 R & M Bldgs - Repairs & Maint 362705 10/01/2013 1,750.00 Repair Works On Cromer Pier As REEVE PROPERTY RESTORATION North Norfolk33UF District CouncilASSETS Assets & Leisure B Premises 2000 R & M Bldgs - Repairs & Maint 362711 10/01/2013 1,976.00 Reeve Property Restoration REEVE PROPERTY RESTORATION North Norfolk33UF District CouncilASSETS Assets & Leisure B Premises 2000 R & M Bldgs - Repairs & Maint 363328 23/01/2013 2,640.00 Reeve Property Restoration REEVE PROPERTY RESTORATION North Norfolk33UF District CouncilASSETS Assets & Leisure B Premises 2001 R & M Buildings - Vandalism -

First Draft Local Plan (Part 1) Interim Consultation Statement

FIRST DRAFT LOCAL PLAN (PART 1) INTERIM CONSULTATION STATEMENT www.north-norfolk.gov.uk/localplan Important Information Document Availability Please note that many of the studies and reports referred to throughout this document can be viewed or downloaded at: www.north-norfolk.gov.uk/documentlibrary. If a document produced by the Council is not available please contact us with your request. All Council produced documents referred to can be viewed at North Norfolk District Council Main Offices in Cromer during normal office hours. Ordnance Survey Terms & Conditions You are granted a non-exclusive, royalty free, revocable licence solely to view the Licensed Data for non- commercial purposes for the period during which North Norfolk District Council makes it available. You are not permitted to copy, sub-license, distribute, sell or otherwise make available the Licensed Data to third parties in any form. Third party rights to enforce the terms of this licence shall be reserved to OS. North Norfolk District Council Planning Policy Team 01263 516318 [email protected] Planning Policy, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, NR27 9EN www.north-norfolk.gov.uk/localplan All documents can be made available in Braille, audio, large print or in other languages. Please contact 01263 516318 to discuss your requirements. First Draft Local Plan - Interim Consultation Statement Contents Introduction 1 Introduction 1 Purpose of the Consultation Statement 1 Legislation and the Statement of Community Involvement 1 Relationship -

The Life Saving Awards Research Society

THE LIFE SAVING AWARDS RESEARCH SOCIETY Journal No. 98 August 2020 DIXON’S MEDALS (CJ & AJ Dixon Ltd.) Publishers of Dixon’s Gazette Subscription: for 4 issues UK £20 including p&p Europe £25. Overseas £30 including airmail p&p th Charles Smith ‘Wreck of the Newminster 29 September 1897’ AVAILABLE AT DIXON’S MEDALS www.dixonsmedals.co.uk Email [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)1262 676877 / 603348 1ST FLOOR, 23 PROSPECT STREET, BRIDLINGTON EAST YORKSHIRE, YO15 2AE, ENGLAND J98 IFC - Dixon.indd 1 28/07/2020 09:36:47 THE LIFE SAVING AWARDS RESEARCH SOCIETY JOURNAL August 2020 Number 98 A Medal for Gallant Conduct in Industry .................................................................. 3 Gallant Rescue of a Dog ........................................................................................... 13 The SS Arctees and the SS English Trader ............................................................ 14 Whatever Happened to the Exchange Albert Medals? ......................................... 23 Albert Medal Gallery – Eric William Kevin Walton, GC, DSC .................................. 26 Maori Jack .................................................................................................................. 30 The Ireland Medal – The First Ten Years (2003-13) ............................................... 33 The Peoples Heroes – Part 2 .................................................................................... 45 An Unknown Life Saver ........................................................................................... -

SS HJØRDIS “The Forgotten Ship”

SS HJØRDIS “The Forgotten Ship” Sue Gresham Historical Research Volunteer Researched December 2016 Revised October 2020 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ SS Hjørdis FOREWORD The wreck of the iron steamship SS Hjørdis (English equivalent pronunciation “Yurdis”) has lain off Blakeney Point since she was wrecked and went aground in February 1916. Almost a “ghost ship”, little was known locally about the Hjørdis or of the circumstances which caused her to go aground so close to the shoreline. It was surmised that she might have been the victim of a wartime attack. As the sand moved in, the wreck became almost completely covered. Between 2015 and 2016, the channel moved half a mile to the east and the flow of water over the wreck scoured her out. Exposed by the tides and shifting sands, large sections of the vessel’s hull and deck were uncovered and became clearly visible just below the waterline. SS Hjørdis - 2016 It was particularly poignant that in 2016, one hundred years after the Hjørdis went down, the ship showed herself once again and, as a result, there was a revival of interest in her. My original research in 2016 marked the one hundredth anniversary of the disaster. It presented the history of the ship, her construction, history of ownership, her voyages and the sequence of events which caused her to run aground. It described the attempts that were made to save the vessel and her crew members, outlined how widely the disaster was reported, and speculated on whether the considerable loss of life could have been averted. This updated report includes new information which adds to our knowledge of the Hjørdis and the men who crewed her, not least the man who, against all odds, was the sole survivor. -

Facilities List for Website.Xlsx

Address list of Core operating facilities at March 31, 2021 State Facility Name Facility Type Street Address City County Zip Alabama Avalon Place Skilled Nursing Facility 200 Alabama Avenue Muscle Shoals Colbert 35661 Brookshire Skilled Nursing Facility 4320 Judith Lane Huntsville Madison 35805 Canterbury Health Center Skilled Nursing Facility 1720 Knowles Road Phoenix City Russell 36867 Cottage of the Shoals Skilled Nursing Facility 500 John Aldridge Drive Tuscumbia Colbert 35674 Keller Landing Skilled Nursing Facility 813 Keller Lane Tuscumbia Colbert 35674 Lynwood Nursing Home Skilled Nursing Facility 4164 Halls Mill Road Mobile Mobile 36693 Merrywood Lodge Skilled Nursing Facility 280 Mount Hebron Road, P.O. Box 130 Elmore Elmore 36025 Northside Health Care Skilled Nursing Facility 700 Hutchins Avenue Gadsden Etowah 35901 River City Skilled Nursing Facility 1350 14th Avenue SE Decatur Morgan 35601 Arizona Austin House Assisted Living Facility 195 South Willard Street Cottonwood Yavapai 86326 Encanto Palms Assisted Living Facility 3901 West Encanto Boulevard Phoenix Maricopa 85009 L'Estancia Skilled Nursing Facility 15810 South 42nd Street Phoenix Maricopa 85048 Maryland Gardens Skilled Nursing Facility 31 West Maryland Avenue Phoenix Maricopa 85013 Mesa Christian Skilled Nursing Facility 255 West Brown Road Mesa Maricopa 85201 Palm Valley Skilled Nursing Facility 13575 West McDowell Road Goodyear Maricopa 85338 Ridgecrest Skilled Nursing Facility 16640 North 38th Street Phoenix Maricopa 85032 Santa Catalina Independent Living Facility -

Cod and Herring.Indb

Marine fish consumption in medieval Britain: the isotope perspective from human skeletal remains Book or Report Section Published Version Muldner, G. (2016) Marine fish consumption in medieval Britain: the isotope perspective from human skeletal remains. In: Barrett, J. and Orton, D. (eds.) Cod and herring: the archaeology and history of medieval sea fishing. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp. 239-249. ISBN 9781785702396 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/66232/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Oxbow Books All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online This pdf of your paper in Cod and Herring belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright. As author you are licenced to make up to 50 offprints from it, but beyond that you may not publish it on the World Wide Web until three years from publication (June 2019), unless the site is a limited access intranet (password protected). If you have queries about this please contact the editorial department at Oxbow Books ([email protected]). COD AND HERRING AN OFFPRINT FROM COD AND HERRING THE ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL SEA FISHING Edited by JAMES H. BARRETT -

December 10,1869

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. Established June 23,1862. Vol.8. PORTLAND, FRIDAY MORNING, DECEMBER 10, 1869. Terms $8.00 per annum, in advance. ^ — ————— The Portland Dally Press REMOVALS. INSURANCE. MISCELLANEOUS. MISCELLANEOUS. A Ci.ue seems to be obtained to the origin •-- — 1 — THE DAILY PRESS of the Cardiff Mr. Is published every day (Sundays excepted) by DAILY PRESS. great giant. Wright, city ,h* REMOVAL- FIRF, MARINE. TV O T X C eT BUSINESS DIRECTORY. marshall of Fort Dodge, Iowa, writes to the Portland Publishing Co., PORTLAND editor of the Syracuse Journal that : -AND have this admitted Samuel H. Brackett, Choice At 109 Exchange Street, Portland. day Three years ago next July two men came OUR a in the firm ot SheriJan & Griffiths, Security! WE SHALL OPEN WE partner here from Dollars a We iDvite the attention of both City and D.cembsr 1869. the east and quarried out a mon- Terms:—Eight Year in advance and will continue the Plastering, Stucco and Mastic Friday Morning, 10, strous business in all its branches, uuder the firm name ot gypsum rock, weighing over eight Seven Per Cent, list of Port- thousand Sheridan, Griffiths & Brackett, also have purchased Gold, Country readers to the following pounds. It was hauled on a New Store 49 Life 164 The Maine St, Insurance the stock and stand ot A No. The Men We Raise. to State Press Exchange Jos. Wescott Son, Free of Govexmext Tax. wagon Montana, a distance of miles, Commorcial ot on land BUSINESS which are titty — for the among enormous — OH street, purpose carrying HOUSES, In the few at an expense. -

The Norfolk Ancestor

CoverJun 18.qxp_NorfolkAncestor CoverJun15.qxd 30/04/2018 16:35 Page 1 Then and Now The Norfolk Ancestor JUNE 2018 These two pictures show the junction between Newmarket Road on the right and Ipswich Road on the left outside the old Norfolk and Norwich Hospital. The top one dates from 1876 and the bottom one from 2018. In the 1876 picture you can see the famous Boileau Fountain which sadly is no longer there. To read about the story of the fountain turn to the inside back cover. The Journal of the Norfolk Family History Society formerly Norfolk & Norwich Genealogical Society CoverJun 18.qxp_NorfolkAncestor CoverJun15.qxd 30/04/2018 16:35 Page 3 The Boileau Fountain A Brush with History A few weeks ago a kind lady, Mrs Annetta EVANS, NORWICH and the surrounding area has a long standing association with the handed me a series of photographs of Norfolk and brush making industry with towns like Wymondham and Attleborough becoming Norwich that she had taken over the years and asked important manufacturing centres over the years. Brushes had been made in me if they would be of any interest to the NFHS. Norwich from the eighteenth century and by 1890 there were at least 15 brush When I looked through them, a number of them trig- making firms in the city. gered ideas for articles. The picture on the right was taken in the grounds of the old Norfolk and Norwich One of the most important stories centres Hospital which stands on Newmarket Road. It shows around Samuel DEYNS. -

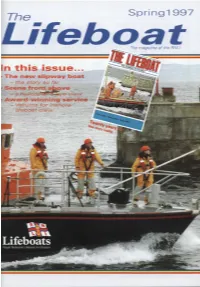

Eyemouth's Trent Class Lifeboat Barclaycard Crusader Launched

The Springl 997 oatThe magazine of the RNLI In this issue... • The new slipway boat — the story so far • Scene from above — a hecoperye vew • Award- winning service — Vellums for inshore lifeboat crew SAVE MONEY ON PETROL SAFELY ACHIEVE MORE POWER, EFFICIENCY AND PERFORMANCE INLONGTE P84ttlCAL MOTORIST FOUND: FUEL ECONOMY • UP 6-9% ROAD WHEEL POWER • UP 2-7% Simply dropped into the fuel tank of any petrol or deisel vehicle, Broquet transforms performance and efficiency - guaranteed. Broquet works in any car, old or new. Its amazing but absolutely true ... Broquet even allows the use of unleaded petrol, without harm, in older cars which were designed for two and four star fuels. No adjustment In 1988 Henry Broquet was awarded che USSR Peace Medal. required! motorist REDUCED FUEL CONSUMPTION Broquet has been proven REDUCED EXHAUST EMISSIONS time and time again and now THE USE OF UNLEADED PETROL you too can install Broquet ON ALL PETROL ENGINES in your car. Simply drop the REDUCED OIL CONSUMPTION catalyst into your fuel tank CLEANER LUBRICATION OIL (leaded, unleaded or diesel) QUIETER RUNNING and save up to 9% of the SMOOTHER ACCELERATION pump price - that's an FEWER GEAR CHANGES amazing saving of between USE SAFELY AND EFFECTIVELY 24-30p per gallon. A single WITH CATALYTIC CONVERTERS catalyst will last over 250,000 miles. " We hereby state that the Broquet Fuel Catalyst cannot in any way prove harmful to an engine. In addition we In long term tests confirm that it is comprehensively Practical Motorist found: FUEL ECONOMY - up 6-9% underwritten by a major insurance company.