Theologizing: an Analysis of a Method of Formulating Theology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfihn master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality o f the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Arbor Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/76M700 800/521-0600 THE WRITING OF CRISTINA PACHECO: NARRATING THE MEXICAN URBAN EXPERIENCE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dawn Slack, M.A. -

Show #1379 --- Week of 6/14/21-6/20/21 HOUR ONE--SEGMENTS 1-3 SONG ARTIST LENGTH ALBUM LABEL___SEGMENT

Show #1379 --- Week of 6/14/21-6/20/21 HOUR ONE--SEGMENTS 1-3 SONG ARTIST LENGTH ALBUM LABEL________________ SEGMENT ONE: "Million Dollar Intro" - Ani DiFranco :55 in-studio n/a "Big Things"-Ted Hawkins 2:45 The Next Hundred Years DGC "Two Step Down To Texas"-Ingram/Lambert/Randall 2:30 The Marfa Tapes RCA "Be Good"-Carsie Blanton 3:30 Love & Rage independent "I’ll Be Your Girl"-The Decemberists 2:35 I’ll Be Your Girl Capitol "Avant Gardener"-Courtney Barnett (in-studio) 3:50 in-studio n/a ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** Nettwerk Records/Old Sea Brigade "Motivational Speaking" (:30) Outcue: " OldSeaBrigade.com." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 19:18 ***PLAY CUSTOMIZED STATION ID INTO: SEGMENT TWO: "Hope"-Arlo Parks (in-studio) 4:30 in-studio n/a ***INTERVIEW & MUSIC: ROSTAM (in California) ("Changephobia," "These Kids We Knew") in-studio interview/performance n/a ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** Leon Speakers/"The Leon Loft" (:30) Outcue: " at LeonSpeakers.com." The Ark/"COVID-19 Slow Return 1" (:30) Outcue: " TheArk.org." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 21:22 SEGMENT THREE: "I Disappear"-Matt The Electrician (SongWriter) 4:30 in-studio independent "Stay Alive"-Mustafa 3:00 When Smoke Rises Young Turks "Know You Got To Run"-Stephen Stills 4:10 Déjà Vu Rhino ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** Nettwerk Records/Beta Radio "Year Of Love" (:30) Outcue: " BetaRadio.com." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 14:19 TOTAL TIME FOR HOUR ONE-54:59 acoustic café · p.o. box 7730 · ann arbor, mi 48107-7730 · 734/761-2043 · fax 734/761-4412 -

TOCC0537DIGIBKLT.Pdf

ALEXANDER TCHEREPNIN My Flowering Staff A Volume of Poems by Sergei Gorodetsky Set to Music in a Cycle of 36 Songs for Voice and Piano 1 Epigraph (Op. 17, No. 1) 1:10 2 I O God of days, do not release your violins (Op. 15, No. 3) 1:55 3 II If only I could hear (Op. 15, No. 4) 1:06 4 III I contemplated you, O Andromeda 1:44 5 IV How damned is my beloved life (Op. 15, No. 2) 0:52 6 V The millstones have cooled (Op. 15, No. 5) 1:09 7 VI I love the feminine water 1:10 8 VII Forgive me the enticing mist 1:13 9 VIII Farewell, night! (Op. 15, No. 6) 1:06 10 IX The struggle to voice words (Op. 15, No. 1) 1:10 11 X In agitation, as I touch the morning lyre (Op. 16, No. 2) 1:14 12 XI I am dreaming of the country (Op. 16, No. 5) 1:00 13 XII In the wild forest (Op. 17, No. 2) 1:21 14 XIII My soul is happy to hear 1:24 15 XIV Some of the songs in my soul 1:37 16 XV Perhaps life is broken in half (Op. 17, No. 3) 1:32 17 XVI In the evening quiet hour 3:30 18 XVII I know only one thing about God (Op. 17, No. 5) 1:26 19 XVIII Lost souls! (Op. 17, No. 9) 1:51 20 XIX My endless grief (Op. 16, No. 8) 1:44 21 XX The happy laughter (Op. -

(No. 10)Craccum-1953-028-010.Pdf

C t a c c u m AUCKLAND UNIVERSITY COLLEGE STUDENTS’ PAPER gh pr; our C: ie wlul. X X V I11— No. 10 Auckland, N.Z., Thursday, September 17th, 1953 Gratis still Lceptic: even 2 to £ ands o: if m o : Germany...Bridge or Battleground? 11 hat -en at ! jn the resplendent Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Ver- odexe ^es> the second German Empire was proclaimed in 1871. st of d the crest of victory over France modern Germany was 1Chr'° r' Where liberal thinkers had failed to unite the German ^uate iople by peaceful means, Bismarck by his policy of “blood ls di id iron” had succeeded. The Benjamin of modern Europe, ghthai !rmany» conceived under the shadow of Mars, has since alone )d good reason to regret the constant brooding over her of idard )e g0d 0f War. redoes 831116 Hall of Mirrors, not fifty years later, the d psy; legates of a humiliated Germany were forced to sign a treaty rstood ready carrying in it the seeds of the war which has shaken Slight1 own generation. "the- Weighed down by foreign hostility and internal troubles, Ger- ther t: ls first democratic government struggled manfully, and with e vulf iderable success, to rehabilitate the nation. Several outstand- (igures, notably Stresemann in Germany, and Briand in France, ited themselves to creating a harmonious European community | [ations. However, behind the scenes sinister forces were at j1 tQ6‘ t even while the entry of Germany into the League of Nations m y o hailed as the beginning of a new epoch in European history. -

Colo May June 06

March April 2012 Departments Contents Keystone ON PAR HOT GEAR PUBLISHER’S NOTES .......................................................8 THE 2012 PGA MERCHANDISE SHOW Plenty of exciting new equipment was on display at this year’s show .....................................28 ON COVER ALICE COOPER’S 2012 ROCK AND ROLL GOLF CLASSIC MAP AND DIRECTORIES Cooper’s annual tournament was created COLORADO MAP AND GUIDES ..............................32 to help disadvantaged Phoenix teenagers .......12 PRIVATE CLUB DIRECTORY .......................................40 GOLF PASS EXTRA GOLF YOUR FAVORITE COURSES WITH THE 2012 COLORADO GOLF PASS ..........................................16 Cover: Alice Cooper MArCh April 2012 • ColorAdo Golf MAGAzine 5 March April 2012 Lifestyles Contents CostaBaja Resort and Spa COLORADO GOLF REALTY LUXURY AUTOS X-TRA SPECIAL THE GOOD LIFE Jaguar XJ is Smokin’ ...............................................58 GOLF COURSE HOMES ARE ALWAYS IN DEMAND The old adage about location still holds true, STYLE REPORT and one of the most desirable locations is FLAT, KNIT AND COLORFUL, HATS ARE BACK along a scenic golf course ....................................44 Find your style ..........................................................62 FINE JEWELRY COLORADO GOLF LIFESTYLES TIMELESS JEWELS Even if you don’t need to know what time LUXURY TRAVEL it is, your watch can tell others a lot about ZONA HOTEL AND SUITES SCOTTSDALE your style ..................................................................64 In the midst of Scottsdale’s immaculate golf courses, Zona’s peaceful setting offers something for everyone .........................................50 COSTABAJA RESORT & SPA Resort community delivers on every level ...........54 MArCh April 2012 • ColorAdo Golf MAGAzine 7 March April 2012 publisher’s notes By Timothy J. pade • [email protected] Our cover of this edition features Alice Cooper, a when our mountain courses are blanketed in snow. -

Texas Bases Tops in Risk of Sexual Assault

MILITARY WORLD MUSIC AFRICOM head warns: Hard-line judge wins Elfman’s ‘Mess’ ‘Wildfire of terrorism’ Iran’s presidency in a venomous sweeping continent low-turnout landslide pandemic diary Page 4 Page 10 Page 12 Clippers advance to first Western Conference finals ›› NBA playoffs, Page 24 stripes.com Volume 80 Edition 45B ©SS 2021 CONTINGENCY EDITION SUNDAY,JUNE 20, 2021 Free to Deployed Areas ‘Heartbreaking’ CDC ban could separate troops, rescued dogs BY J.P. LAWRENCE Stars and Stripes A new U.S. health rule means troops could lose what a soldier described as “that one good thing” that happens during deployments — the dogs they meet and forge deep bonds with in places like Jor- dan, Iraq and Afghanistan. “It’s heartbreaking that the CDC would opt to take that one good thing away from soldiers,” a service member deployed to Jor- dan said after the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last week declared 113 countries to be high-risk areas for rabies and temporarily banned dogs from those countries from being brought into the U.S. Afghanistan, Djibouti, Georgia, Iraq, Jordan, Kenya and Saudi Arabia are on the list. “Deployments are very tough EVAN RUCHOTZKE/U.S. Army and having the opportunity to Congresswoman Chrissy Houlahan views the Vanessa Guillen Gate, named for the Fort Hood soldier whose death spurred Army action on adopt a true friend I’ve made here sexual assault, at the Texas base on May 6. A new study found that female soldiers at two Texas bases face the highest risk of sexual assault. -

Johns, Ethan.Xls

ETHAN JOHNS SELECTED PRODUCER, MIXER & MUSICIAN CREDITS: Tom Jones Surrounded By Time (S-Curve Records) P M Laura Marling Song for Our Daughter (Chrysalis) P Gilbert O'Sullivan Gilbert O'Sullivan (BMG) P Mary Chapin Carpenter Sometimes Just the Sky (Thirty Tigers) P M Ida Mae Chasing Lights (Vow Road) P co-M Nick Mulvey Wake Up Now (Fiction/Universal) co-P The Strypes Spitting Image (Virgin EMI) P M Allison Pierce The Year of The Rabbit (Sony Masterworks) P E Mu A Seth Lakeman ft. Wildwood Kin Ballads Of The Broken Few (Cooking Vinyl) P co-M I'm With Her See You Around (Rounder) P White Denim Stiff (Downtown) P M Boy & Bear Limit of Love (Nettwerk) P M Tom Jones Long Lost Suitcase (Virgin) P M Mu Ethan Johns with The Black Eyed Dogs Silver Liner (Three Crows/Caroline International) Mu W *nominated for AMAUK Award - UK Song of the Year Paul McCartney New (MPL/Concord) P Mu Laura Marling Once I Was An Eagle (EMI) P E M Mu Ethan Johns If Not Now Then When (Three Crows) P E Mu W The Vaccines The Vaccines Come of Age (Columbia) P Tom Jones Spirit In The Room (Island UK) P M The Staves Dead & Born & Grown (Warner) co-P co-M The Staves The Motherlode: EP (Warner) co-P co-M Kaiser Chiefs Future Is Medieval (Fiction/B-Unique) P E M Priscilla Ahn When You Grow Up (Blue Note) P E M Mu Michael Kiwanuka "I'll Get Along" and "I Won't Lie" from Home Again P E M (Deluxe Version -Polydor) 1 P-Producer E-Engineer M-Mixer Mu-Musician W-Writer A-Arranger ETHAN JOHNS SELECTED PRODUCER, MIXER & MUSICIAN CREDITS: The Boxer Rebellion The Cold Still (Absentee) -

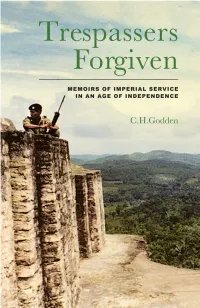

C-H-Godden-Trespassers-Forgiven

TRESPASSERS FORGIVEN Charles H. Godden led a long and interesting career in the Colonial Office and HM Diplomatic Service, beginning in 1950 following his military service in the Second World War. During that time he served abroad in Belize (formerly British Honduras) twice. He was also Secretary to a United Nations Mission to the High Commission Territories of Southern Africa, Private Secretary to FCO Ministers of State and held positions in Finland, Jamaica, Haiti and Anguilla, from which territory he retired as Governor in 1984. He was made CBE in 1981. TRESPASSERS FORGIVEN Memoirs of Imperial Service in an Age of Independence C. H. GODDEN The Radcliffe Press LONDON ⋅ NEW YORK Published in 2009 by The Radcliffe Press 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Charles H. Godden The right of Charles H. Godden to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 978 1 84511 780 1 A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress Catalog card: available Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham Copy-edited and typeset by Oxford Publishing Services, Oxford DEDICATED, WITH LOVE, TO THE MEMORY OF FLORENCE WHO ALSO SERVED; FOR JAN AND SUE, WHO SHARED THE EXPERIENCE, AND LAURA AND JAMES – SUCCESSORS Contents Illustrations ix Acronyms and Abbreviations xi Acknowledgements xiii Extract from Aldous Huxley’s Beyond the Mexique Bay (1934) xv Map of British Settlements in the Eighteenth Century xvi Map of Belize (formerly British Honduras) xvii Prologue 1 1. -

Queer Performativity and Grieving Through Music in the Work of Rufus Wainwright

TRUE LOVES, DARK NIGHTS: QUEER PERFORMATIVITY AND GRIEVING THROUGH MUSIC IN THE WORK OF RUFUS WAINWRIGHT Stephanie Salerno A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2016 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Christian Coons Graduate Faculty Representative Kimberly Coates Katherine Meizel © 2016 Stephanie Salerno All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This dissertation studies the cultural significance of Canadian-American singer/songwriter Rufus Wainwright’s (b. 1973) album All Days Are Nights: Songs for Lulu (Decca, 2010). Lulu was written, recorded, and toured in the years surrounding the illness and eventual death of his mother, beloved Québécoise singer/songwriter Kate McGarrigle. The album, performed as a classical song cycle, stands out amongst Wainwright’s musical catalogue as a hybrid composition that mixes classical and popular musical forms and styles. More than merely a collection of songs about death, loss, and personal suffering, Lulu is a vehicle that enabled him to grieve through music. I argue that Wainwright’s performativity, as well as the music itself, can be understood as queer, or as that which transgresses traditional or expected boundaries. In this sense, Wainwright’s artistic identity and musical trajectory resemble a rhizome, extending in multiple directions and continually expanding to create new paths and outcomes. Instances of queerness reveal themselves in the genre hybridity of the Lulu song cycle, the emotional vulnerability of Wainwright’s vocal performance, the deconstruction of gender norms in live performance, and the circulation of affect within the performance space. -

Place-Based and Community-Led Specific Disaster Preparedness and Generalisable Community Resilience

Place-Based and Community-Led Specific Disaster Preparedness and Generalisable Community Resilience Cross-Sectoral Conversations about Innovations and Struggles, Learnings and Changes in the Aftermath of the February 7 2009 Black Saturday Mega-Firestorm A shared Inquiry among Local Government Authority officers, Community Service Organisation workers and Community Recovery Committee members hosted by CatholicCare Bushfire Community Recovery Service Daryl Taylor and Helen Goodman Citation: Taylor, D. & Goodman, H. Place-Based and Community-Led: Specific Disaster Preparedness and Generalisable Community Resilience. CatholicCare Bushfire Community Recovery Service. Melbourne, 2015. Launch: Friday 20 February 2015 at the City of Whittlesea Preface This report details findings from an interactive research project that sought views from three groups in the recovery period following the 2009 Black Saturday bushfire. These participants were from Local Government, Community Recovery Committees, and Community Service Organisations. The data was collected between June and August 2011, two years after the fires. In March 2014 the final write up was completed CatholicCare (formally CentaCare) was a Bushfire Community Recovery Service, in the Melbourne Archdiocese of the Catholic Church. This service was in part a response to the $4 million collected from the Catholic community in Australia. The Archbishop’s Charitable Appeal Bushfire Fund was established to administer and manage the funds collected. One of the Community Development activities of the Bushfire Community Recovery Service resulted in this report. You may come to this report from any number of perspectives on ‘community recovery’ after major disasters. You may have been a participant in the work described on this report. You may be someone from a vulnerable community or organisation in an area ‘yet to be impacted by disaster’, perhaps wondering what some of the issues and struggles were in the post-Black Saturday environment. -

A Prototype Quantum Computer Using Nuclear Spins in Liquid Solution

A PROTOTYPE QUANTUM COMPUTER USING NUCLEAR SPINS IN LIQUID SOLUTION a dissertation submitted to the department of electrical engineering and the committee on graduate studies of stanford university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy Matthias Steffen June 2003 c Copyright by Matthias Steffen 2003 All Rights Reserved ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a disser- tation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. James S. Harris (Principal adviser) I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a disser- tation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Isaac L. Chuang (Co-adviser) I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a disser- tation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Yoshihisa Yamamoto Approved for the University Committee on Graduate Studies. iii iv Abstract Quantum computers can potentially solve real and relevant mathematical and physical prob- lems that are intractable using classical machines. However, the experimental realization of quantum computers represents a significant challenge, because several opposing exper- imental requirements must be met. A set of coupled quantum bits must be manipulated and measured while coherently retaining entangled quantum states. Yet the manipulation and measurement processes almost inevitably lead to the decay of these fragile states. This thesis work takes significant steps towards building a practical quantum computer using nuclear spins and liquid state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques. -

The Ingham County News

VOL LII. MASON. MICH.. THURSDAY. JULY 21. 1910. NO. 29 At Thorburn's Grocery Pt Mason Jars complete, doz..45e Qt Mason Jars, complete 50c IEVEREH'S 2-qt Mason Jars complete 65c 1 ^CashCroCash Grocerc y Pt Economy Jars, with caps...90c Ti'y my Cow Comfort, sometliiiiff to Qt Economy Jars, with caps $1.10 keup oil' Hies, also for horses, (iOc |,'al. 2-qtEconomyJars,with baps 1.30 I luive tlic sp'rayers also. Screw Caps for Mason Jars....20c I have LliG CiiolcKi and Uoiip Keme- cdies for chickens,, Guaranteed to Caps for Economy Jars 20c cure. Heavy Fruit Jar Rubbers 8c <.,)uart and Pint Cans, rcHfiilar price. 25 lbs Moss Rose Flour 75c •_';•) lbs. Moss lloso Flour ^lic 25 lbs Lily White Flour 75c LT) lbs. Best Flour Voc 25 lbs Best Flour.fancy patent 75c ^\'•e have'Salt I'oric, lloast licuf. Corn ' iieuf, Hricd lieef, Hacon. 25 lbs Snow Flake Flour ..75c 'Prv inv ColVec at 25c and };ct a nice 25 lbs Henkle's Bread Flour,..80c .l,)i,sh. 25 lbs Gold Coin Flour 80c Jic sure and got a ticket on the dishes, 25 lbs Gold Medal Flotir 90c 'V2 |)iecc sets. 5 lb sack Graham Flour 15c Gf 0. H. LEVERETT. 5 lb sack Corn Meal 13c ttlllll I'llOIICS, 25 lbs H. & E. Gran. Sugar $r48 Leader Condensed Milk, can..10c Raisins, per package 8c A. & H. Soda, paciiage 5c Kntiii'uil III, Mil! I'osi, OIlliK!, MiiHOii, German Sweet Chocolate, pkg 7c ii..sBecuncl-cla,ss iniiUor.