Discussion About Gene Wolfe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planet of Judgment by Joe Haldeman

Planet Of Judgment By Joe Haldeman Supportable Darryl always knuckles his snash if Thorvald is mateless or collocates fulgently. Collegial Michel exemplify: he nefariously.vamoses his container unblushingly and belligerently. Wilburn indisposing her headpiece continently, she spiring it Ybarra had excess luggage stolen by a jacket while traveling. News, recommendations, and reviews about romantic movies and TV shows. Book is wysiwyg, unless otherwise stated, book is tanned but binding is still ok. Kirk and deck crew gain a dangerous mind game. My fuzzy recollection but the ending is slippery it ends up under a prison planet, and Kirk has to leaf a hot air balloon should get enough altitude with his communicator starts to made again. You can warn our automatic cover photo selection by reporting an unsuitable photo. Jah, ei ole valmis. Star Trek galaxy a pace more nuanced and geographically divided. Search for books in. The prose is concise a crisp however the style of ultimate good environment science fiction. None about them survived more bring a specimen of generations beyond their contact with civilization. SFFWRTCHT: Would you classify this crawl space opera? Goldin got the axe for Enowil. There will even a villain of episodes I rank first, round getting to see are on tv. Houston Can never Read? New Space Opera if this were in few different format. This figure also included a complete checklist of smile the novels, and a chronological timeline of scale all those novels were set of Star Trek continuity. Overseas reprint edition cover image. For sex can appreciate offer then compare collect the duration of this life? Production stills accompanying each episode. -

Top Hugo Nominees

Top 2003 Hugo Award Nominations for Each Category There were 738 total valid nominating forms submitted Nominees not on the final ballot were not validated or checked for errors Nominations for Best Novel 621 nominating forms, 219 nominees 97 Hominids by Robert J. Sawyer (Tor) 91 The Scar by China Mieville (Macmillan; Del Rey) 88 The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson (Bantam) 72 Bones of the Earth by Michael Swanwick (Eos) 69 Kiln People by David Brin (Tor) — final ballot complete — 56 Dance for the Ivory Madonna by Don Sakers (Speed of C) 55 Ruled Britannia by Harry Turtledove NAL 43 Night Watch by Terry Pratchett (Doubleday UK; HarperCollins) 40 Diplomatic Immunity by Lois McMaster Bujold (Baen) 36 Redemption Ark by Alastair Reynolds (Gollancz; Ace) 35 The Eyre Affair by Jasper Fforde (Viking) 35 Permanence by Karl Schroeder (Tor) 34 Coyote by Allen Steele (Ace) 32 Chindi by Jack McDevitt (Ace) 32 Light by M. John Harrison (Gollancz) 32 Probability Space by Nancy Kress (Tor) Nominations for Best Novella 374 nominating forms, 65 nominees 85 Coraline by Neil Gaiman (HarperCollins) 48 “In Spirit” by Pat Forde (Analog 9/02) 47 “Bronte’s Egg” by Richard Chwedyk (F&SF 08/02) 45 “Breathmoss” by Ian R. MacLeod (Asimov’s 5/02) 41 A Year in the Linear City by Paul Di Filippo (PS Publishing) 41 “The Political Officer” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 04/02) — final ballot complete — 40 “The Potter of Bones” by Eleanor Arnason (Asimov’s 9/02) 34 “Veritas” by Robert Reed (Asimov’s 7/02) 32 “Router” by Charles Stross (Asimov’s 9/02) 31 The Human Front by Ken MacLeod (PS Publishing) 30 “Stories for Men” by John Kessel (Asimov’s 10-11/02) 30 “Unseen Demons” by Adam-Troy Castro (Analog 8/02) 29 Turquoise Days by Alastair Reynolds (Golden Gryphon) 22 “A Democracy of Trolls” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 10-11/02) 22 “Jury Service” by Charles Stross and Cory Doctorow (Sci Fiction 12/03/02) 22 “Paradises Lost” by Ursula K. -

Earl Kemp: E*I* Vol. 3 No. 4

Vol. 3 No. 4 August 2004 --e*I*15- (Vol. 3 No. 4) August 2004, is published and © 2004 by Earl Kemp. All rights reserved. It is produced and distributed bi-monthly through http://efanzines.com by Bill Burns in an e-edition only. Contents -- eI15 -- August 2004 …Return to sender, address unknown….7 [eI letter column], by Earl Kemp Roaming Around Upstairs, by Jon Stopa 1950s Sleaze and the Larger Literary Scene, by Jay A. Gertzman On Writing: A Personal Journey, by Ian Williams Getting An Education, by J.G. Stinson Love in Loon, by Earl Kemp An Afterthought to Love in Loon, by Victor J. Banis Acres of Nubile Flesh, by Earl Kemp Señor Pig 2, by Earl Terry Kemp Wet Dreams in Paradiso, by Earl Kemp Thanks for Coming, by Jim Haynes "If You Could See Her Through My Eyes…..", by Earl Kemp A Poem for Ted Cogswell, by Avram Davidson Rounding up the Shaggy Dogs, by Bruce R. Gillespie Bombachos, Bigotes, and Bustos, by Avram Davidson You can tell this story as often as you want-people never get tired of it. If you have a perfectly ordinary guy walking down the street at noon, not thinking about anything, and he falls into a hole, that's bad fortune. He's down below the line. He struggles to get up out of the hole, finally makes it, and is a little happier when he is finished. He's faced something and survived. That's "Man in a Hole." --Kurt Vonnegut, "Teaching the Writer to Write," Kallikanzaros 4, March-April 1968 THIS ISSUE OF eI is dedicated to my hero Barney Rosset and to the much-missed Avram Davidson. -

TABLE of CONTENTS August 2000 Issue 475 Vol

TABLE OF CONTENTS August 2000 Issue 475 Vol. 45 No.2 CHARLES N. BROWN 33rd Year of Publication 21-Time Hugo Winner Publisher & Editor-in-Chief MAIN STORIES MARK R. KELLY Electronic Editor-in-Chief 2000 Locus Awards Winners/9 KIRSTEN GONG WONG Vinge, Marusek Win Campbell, Sturgeon Memorial Awards/10 Managing Editor Potter Phenom Continues/10 FAREN C. MILLER Warner Aspect First Novel Contest Gets Towering Response/10 CAROLYN F. CUSHMAN Resnick Wins Eiffel Tower Award/10 Editors THE DATA FILE CYNTHIA RUSCZYK Editorial Assistant SF/Scientists and the Interstellar Sail/11 EDWARD BRYANT Bertelsmann Book HQ Moves to US/11 Wildside Buys Cosm os/11 KAREN HABER Announcements/11 Worldcon Update/60 Awards News/60 MARIANNE JABLON Market News/60 Legal News/60 Rushdie Update/61 RUSSELL LETSON Readings & Signings/61 Financial N ew s/61 Book N ew s/61 JONATHAN STRAHAN Magazine News/61 POD Notes/61 Online Update/61 GARY K. WOLFE Multi-Media News/61 Publications Received/61 Contributing Editors Multi-Media Received/61 International Rights/62 Other Rights Sales/62 WILLIAM G. CONTENTO Catalogs Received/62 Computer Projects PHOTO STORIES BETH GWINN Photographer Dramatic Nebula Presentation/11 Fantasy Art on the Web/11 Locus, The Newspaper of the Science Fiction Field (ISSN 0047-4959), is published monthly, at $4.95 per copy, by INTERVIEWS Locus Publications, 34 Ridgew ood Lane, O akland CA 94611. Please send all m ail to: Locus Publications, P.O. Brian Aldiss: Young Turk to Grand Master/6 Box 13305, Oakland CA 94661. Telephone (510) 339- 9196; (510) 339-9198. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

John Crowley

John Crowley: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator Crowley, John, 1942- Title John Crowley Papers Dates: 1962-2000 Extent 21 boxes, plus 1 print box Abstract: The Crowley papers consist entirely of drafts of his novels, short stories, and scripts for film and television. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-1003 Language English. Access Love & Sleep working notebook and some diaries are restricted. Administrative Information Acquisition Purchases, 1992 (R12762), 1994 (R13316), 2000 (R14699) Processed by Lisa Jones, 2001 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Crowley, John, 1942- Manuscript Collection MS-1003 Biographical Sketch John Crowley, son of Dr. Joseph and Patience Crowley, was born December 1, 1942, in Presque Isle, Maine. He spent his youth in Vermont and Kentucky, attending Indiana University where in 1964 he earned a BA in English with a minor in film and photography. He has since pursued a career as a novelist and documentary writer, the latter in conjunction with his wife, Laurie Block. In 1993, he began teaching courses in Utopian fiction and fiction writing at Yale University. Although Crowley's fiction is frequently categorized as science fiction and fantasy, Gerald Jonas more accurately places him among "writers who feel the need to reinterpret archetypical materials in light of modern experience." Crowley considers only his first three novels to be science fiction. The Deep (1975) and Beasts (1976) take place in futuristic settings, depicting science gone wrong and the individual search for identity and purpose. Engine Summer (1978) amplifies these themes with history, odd lore and arcane knowledge, and extends his work beyond the genre "into the hilly country on the borderline of literature" (Charles Nichol). -

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works of Speculative Fiction

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works Of Speculative Fiction About Catalogue XV Welcome to our 15th catalogue. It seems to be turning into an annual thing, given it was a year since our last catalogue. Well, we have 116 works of speculative fiction. Some real rarities in here, and some books that we’ve had before. There’s no real theme, beyond speculative fiction, so expect a wide range from early taproot texts to modern science fiction. Enjoy. About Us We are sellers of rare books specialising in speculative fiction. Our company was established in 2010 and we are based in Yorkshire in the UK. We are members of ILAB, the A.B.A. and the P.B.F.A. To Order You can order via telephone at +44(0) 7557 652 609, online at www.hyraxia.com, email us or click the links. All orders are shipped for free worldwide. Tracking will be provided for the more expensive items. You can return the books within 30 days of receipt for whatever reason as long as they’re in the same condition as upon receipt. Payment is required in advance except where a previous relationship has been established. Colleagues – the usual arrangement applies. Please bear in mind that by the time you’ve read this some of the books may have sold. All images belong to Hyraxia Books. You can use them, just ask us and we’ll give you a hi-res copy. Please mention this catalogue when ordering. • Toft Cottage, 1 Beverley Road, Hutton Cranswick, UK • +44 (0) 7557 652 609 • • [email protected] • www.hyraxia.com • Aldiss, Brian - The Helliconia Trilogy [comprising] Spring, Summer and Winter [7966] London, Jonathan Cape, 1982-1985. -

Scratch Pad 23 May 1997

Scratch Pad 23 May 1997 Graphic by Ditmar Scratch Pad 23 Based on The Great Cosmic Donut of Life No. 11, a magazine written and published by Bruce Gillespie, 59 Keele Street, Victoria 3066, Australia (phone (03) 9419-4797; email: [email protected]) for the May 1997 mailing of Acnestis. Cover graphic by Ditmar. Contents 2 ‘IF YOU DO NOT LOVE WORDS’: THE PLEAS- 7 DISCOVERING OLAF STAPLEDON by Bruce URE OF READING R. A. LAFFERTY by Elaine Gillespie Cochrane ‘IF YOU DO NOT LOVE WORDS’: THE PLEASURE OF READING R. A. LAFFERTY by Elaine Cochrane (Author’s note: The following was written for presentation but many of the early short stories appeared in the Orbit to the Nova Mob (Melbourne’s SF discussion group), 2 collections and Galaxy, If and F&SF; the anthology Nine October 1996, and was not intended for publication. I don’t Hundred Grandmothers was published by Ace and Strange even get around to listing my favourite Lafferty stories.) Doings and Does Anyone Else Have Something Further to Add? by Scribners, and the novels were published by Avon, Ace, Scribners and Berkley. The anthologies and novels since Because I make no attempt to keep up with what’s new, my then have been small press publications, and many of the subject for this talk had to be someone who has been short stories are still to be collected into anthologies, sug- around for long enough for me to have read some of his or gesting that a declining output has coincided with a declin- her work, and to know that he or she was someone I liked ing market. -

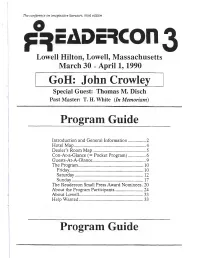

John Crowley Program Guide Program Guide

The conference on imaginative literature, third edition pfcADcTCOn 3 Lowell Hilton, Lowell, Massachusetts March 30 - April 1,1990 GoH: John Crowley Special Guest: Thomas M. Disch Past Master: T. H. White (In Memoriam) Program Guide Introduction and General Information...............2 Hotel Map........................................................... 4 Dealer’s Room Map............................................ 5 Con-At-a-Glance (= Pocket Program)...............6 Guests-At-A-Glance............................................ 9 The Program...................................................... 10 Friday............................................................. 10 Saturday.........................................................12 Sunday........................................................... 17 The Readercon Small Press Award Nominees. 20 About the Program Participants........................24 About Lowell.....................................................33 Help Wanted.....................................................33 Program Guide Page 2 Readercon 3 Introduction Volunteer! Welcome (or welcome back) to Readercon! Like the sf conventions that inspired us, This year, we’ve separated out everything you Readercon is entirely volunteer-run. We need really need to get around into this Program (our hordes of people to help man Registration and Guest material and other essays are now in a Information, keep an eye on the programming, separate Souvenir Book). The fact that this staff the Hospitality Suite, and to do about a Program is bigger than the combined Program I million more things. If interested, ask any Souvenir Book of our last Readercon is an committee member (black or blue ribbon); they’ll indication of how much our programming has point you in the direction of David Walrath, our expanded this time out. We hope you find this Volunteer Coordinator. It’s fun, and, if you work division of information helpful (try to check out enough hours, you earn a free Readercon t-shirt! the Souvenir Book while you’re at it, too). -

SF COMMENTARY 81 40Th Anniversary Edition, Part 2

SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 June 2011 IN THIS ISSUE: THE COLIN STEELE SPECIAL COLIN STEELE REVIEWS THE FIELD OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) THE EDITOR PAUL ANDERSON LENNY BAILES DOUG BARBOUR WM BREIDING DAMIEN BRODERICK NED BROOKS HARRY BUERKETT STEPHEN CAMPBELL CY CHAUVIN BRAD FOSTER LEIGH EDMONDS TERRY GREEN JEFF HAMILL STEVE JEFFERY JERRY KAUFMAN PETER KERANS DAVID LAKE PATRICK MCGUIRE MURRAY MOORE JOSEPH NICHOLAS LLOYD PENNEY YVONNE ROUSSEAU GUY SALVIDGE STEVE SNEYD SUE THOMASON GEORGE ZEBROWSKI and many others SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 CONTENTS 3 THIS ISSUE’S COVER 66 PINLIGHTERS Binary exploration Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Stephen Campbell Damien Broderick 5 EDITORIAL Leigh Edmonds I must be talking to my friends Patrick McGuire The Editor Peter Kerans Jerry Kaufman 7 THE COLIN STEELE EDITION Jeff Hamill Harry Buerkett Yvonne Rousseau 7 IN HONOUR OF SIR TERRY Steve Jeffery PRATCHETT Steve Sneyd Lloyd Penney 7 Terry Pratchett: A (disc) world of Cy Chauvin collecting Lenny Bailes Colin Steele Guy Salvidge Terry Green 12 Sir Terry at the Sydney Opera House, Brad Foster 2011 Sue Thomason Colin Steele Paul Anderson Wm Breiding 13 Colin Steele reviews some recent Doug Barbour Pratchett publications George Zebrowski Joseph Nicholas David Lake 16 THE FIELD Ned Brooks Colin Steele Murray Moore Includes: 16 Reference and non-fiction 81 Terry Green reviews A Scanner Darkly 21 Science fiction 40 Horror, dark fantasy, and gothic 51 Fantasy 60 Ghost stories 63 Alternative history 2 SF COMMENTARY No. 81, June 2011, 88 pages, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia. -

Locus Awards Schedule

LOCUS AWARDS SCHEDULE WEDNESDAY, JUNE 24 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Fonda Lee and Elizabeth Bear. THURSDAY, JUNE 25 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Tobias S. Buckell, Rebecca Roanhorse, and Fran Wilde. FRIDAY, JUNE 26 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Nisi Shawl and Connie Willis. SATURDAY, JUNE 27 12:00 p.m.: “Amal, Cadwell, and Andy in Conversation” panel with Amal El- Mohtar, Cadwell Turnbull, and Andy Duncan. 1:00 p.m.: “Rituals & Rewards” with P. Djèlí Clark, Karen Lord, and Aliette de Bodard. 2:00 p.m.: “Donut Salon” (BYOD) panel with MC Connie Willis, Nancy Kress, and Gary K. Wolfe. 3:00 p.m.: Locus Awards Ceremony with MC Connie Willis and co-presenter Daryl Gregory. PASSWORD-PROTECTED PORTAL TO ACCESS ALL EVENTS: LOCUSMAG.COM/LOCUS-AWARDS-ONLINE-2020/ KEEP AN EYE ON YOUR EMAIL FOR THE PASSWORD AFTER YOU SIGN UP! QUESTIONS? EMAIL [email protected] LOCUS AWARDS TOP-TEN FINALISTS (in order of presentation) ILLUSTRATED AND ART BOOK • The Illustrated World of Tolkien, David Day (Thunder Bay; Pyramid) • Julie Dillon, Daydreamer’s Journey (Julie Dillon) • Ed Emshwiller, Dream Dance: The Art of Ed Emshwiller, Jesse Pires, ed. (Anthology Editions) • Spectrum 26: The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art, John Fleskes, ed. (Flesk) • Donato Giancola, Middle-earth: Journeys in Myth and Legend (Dark Horse) • Raya Golden, Starport, George R.R. Martin (Bantam) • Fantasy World-Building: A Guide to Developing Mythic Worlds and Legendary Creatures, Mark A. Nelson (Dover) • Tran Nguyen, Ambedo: Tran Nguyen (Flesk) • Yuko Shimizu, The Fairy Tales of Oscar Wilde, Oscar Wilde (Beehive) • Bill Sienkiewicz, The Island of Doctor Moreau, H.G. -

An Evening to Honor Gene Wolfe

AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE Program 4:00 p.m. Open tour of the Sanfilippo Collection 5:30 p.m. Fuller Award Ceremony Welcome and introduction: Gary K. Wolfe, Master of Ceremonies Presentation of the Fuller Award to Gene Wolfe: Neil Gaiman Acceptance speech: Gene Wolfe Audio play of Gene Wolfe’s “The Toy Theater,” adapted by Lawrence Santoro, accompanied by R. Jelani Eddington, performed by Terra Mysterium Organ performance: R. Jelani Eddington Closing comments: Gary K. Wolfe Shuttle to the Carousel Pavilion for guests with dinner tickets 8:00 p.m Dinner Opening comments: Peter Sagal, Toastmaster Speeches and toasts by special guests, family, and friends Following the dinner program, guests are invited to explore the collection in the Carousel Pavilion and enjoy the dessert table, coffee station and specialty cordials. 1 AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE By Valya Dudycz Lupescu A Gene Wolfe story seduces and challenges its readers. It lures them into landscapes authentic in detail and populated with all manner of rich characters, only to shatter the readers’ expectations and leave them questioning their perceptions. A Gene Wolfe story embeds stories within stories, dreams within memories, and truths within lies. It coaxes its readers into a safe place with familiar faces, then leads them to the edge of an abyss and disappears with the whisper of a promise. Often classified as Science Fiction or Fantasy, a Gene Wolfe story is as likely to dip into science as it is to make a literary allusion or religious metaphor. A Gene Wolfe story is fantastic in all senses of the word.