Sociobiology and Sociology - R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sensory and Cognitive Adaptations to Social Living in Insect Societies Tom Wenseleersa,1 and Jelle S

COMMENTARY COMMENTARY Sensory and cognitive adaptations to social living in insect societies Tom Wenseleersa,1 and Jelle S. van Zwedena A key question in evolutionary biology is to explain the solitarily or form small annual colonies, depending upon causes and consequences of the so-called “major their environment (9). And one species, Lasioglossum transitions in evolution,” which resulted in the pro- marginatum, is even known to form large perennial euso- gressive evolution of cells, organisms, and animal so- cial colonies of over 400 workers (9). By comparing data cieties (1–3). Several studies, for example, have now from over 30 Halictine bees with contrasting levels of aimed to determine which suite of adaptive changes sociality, Wittwer et al. (7) now show that, as expected, occurred following the evolution of sociality in insects social sweat bee species invest more in sensorial machin- (4). In this context, a long-standing hypothesis is that ery linked to chemical communication, as measured by the evolution of the spectacular sociality seen in in- the density of their antennal sensillae, compared with sects, such as ants, bees, or wasps, should have gone species that secondarily reverted back to a solitary life- hand in hand with the evolution of more complex style. In fact, the same pattern even held for the socially chemical communication systems, to allow them to polymorphic species L. albipes if different populations coordinate their complex social behavior (5). Indeed, with contrasting levels of sociality were compared (Fig. whereas solitary insects are known to use pheromone 1, Inset). This finding suggests that the increased reliance signals mainly in the context of mate attraction and on chemical communication that comes with a social species-recognition, social insects use chemical sig- lifestyle indeed selects for fast, matching adaptations in nals in a wide variety of contexts: to communicate their sensory systems. -

Following the Trail of Ants: an Examination of the Work of E.O

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU Writing Across the Curriculum Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) 2012 Following The rT ail Of Ants: An Examination Of The orW k Of E.O. Wilson Samantha Kee Sacred Heart University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/wac_prize Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Entomology Commons, Other Genetics and Genomics Commons, Philosophy of Science Commons, Religion Commons, and the Theory, Knowledge and Science Commons Recommended Citation Kee, Samantha, "Following The rT ail Of Ants: An Examination Of The orkW Of E.O. Wilson" (2012). Writing Across the Curriculum. 2. http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/wac_prize/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Writing Across the Curriculum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Samantha Kee RS 299-Writing With Public Purpose Dr. Brian Stiltner March 2, 2012 Following the trail of ants An examination of the work of E.O. Wilson Edward Osborne Wilson was a born naturalist, in every sense of the word. As a child growing up in Alabama, he collected and studied species of snakes, flies, and the insect that became the basis of his life’s work, ants. He made a goal to record every species of ant that could be found in Alabama—a childhood project that would eventually lead to his first scientific publication. By age 13, Wilson discovered a red, non-native ant in a local town in Alabama, and by the time he entered the University of Alabama, the fire ant had become a significant threat to the state’s agriculture. -

Biogeography and Ecology of New Guinea Edited by J.L. Gressitt Dr W

Book reviews Biogeography and Ecology of New of documentation, analysis and interpretation is Guinea put over with a style and spirit that prevents such a Edited by J.L. Gressitt heavyweight work from becoming too stodgy. Dr W. Junk, 2 vols, US $195, DFL.450 Norman Myers The opening sentence of this splendid work sums it up: 'New Guinea is a fantastic island, unique Darwinism Defended; a guide to the and fascinating'. The largest tropical island and evolution controversies the highest island (with glaciers), it features Michael Ruse extraordinary bio-ecological diversity: some 9000 species of plants, many of them endemic; Addison Wesley, £6-95 more than 200 mammals, almost two-thirds of For a century it has been taken for granted that which are unique to the island; at least 570 birds; Darwin had solved the question to why there is a 170 lizards; 200 frogs; probably 10,000 species of myriad of species on earth. Many people now beetles, and around 20,000 species of other think otherwise and the theory of evolution by arthropods. Yet these figures, remarkable as they natural selection is under assault from several are, refer only to known and documented branches of enquiry; some philosophers think species: the numbers awaiting scientific attention that the theory is nothing more than empty could well be much greater. Along the southern rhetoric, some scientists think evolution occurs in edge of the island the climate is seasonal, thus jerks and thus negates the gradualist requirement engendering ecological variety, and the geologic of Darwin's theory and others believe that the upheavals of the recent past have induced patterns of life on earth are by the hand of an sufficient 'creative disruption' to stimulate the omniscient creator. -

The Evolutionary Biology of Decision Making

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of Psychology Psychology, Department of 2008 The Evolutionary Biology of Decision Making Jeffrey R. Stevens University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/psychfacpub Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Stevens, Jeffrey R., "The Evolutionary Biology of Decision Making" (2008). Faculty Publications, Department of Psychology. 523. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/psychfacpub/523 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of Psychology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in BETTER THAN CONSCIOUS? DECISION MAKING, THE HUMAN MIND, AND IMPLICATIONS FOR INSTITUTIONS, ed. Christoph Engel and Wolf Singer (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008), pp. 285-304. Copyright 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology & the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies. Used by permission. 13 The Evolutionary Biology of Decision Making Jeffrey R. Stevens Center for Adaptive Behavior and Cognition, Max Planck Institute for Human Development, 14195 Berlin, Germany Abstract Evolutionary and psychological approaches to decision making remain largely separate endeavors. Each offers necessary techniques and perspectives which, when integrated, will aid the study of decision making in both humans and nonhuman animals. The evolutionary focus on selection pressures highlights the goals of decisions and the con ditions under which different selection processes likely influence decision making. An evolutionary view also suggests that fully rational decision processes do not likely exist in nature. -

Evolution by Natural Selection, Formulated Independently by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace

UNIT 4 EVOLUTIONARY PATT EVOLUTIONARY E RNS AND PROC E SS E Evolution by Natural S 22 Selection Natural selection In this chapter you will learn that explains how Evolution is one of the most populations become important ideas in modern biology well suited to their environments over time. The shape and by reviewing by asking by applying coloration of leafy sea The rise of What is the evidence for evolution? Evolution in action: dragons (a fish closely evolutionary thought two case studies related to seahorses) 22.1 22.4 are heritable traits that with regard to help them to hide from predators. The pattern of evolution: The process of species have changed evolution by natural and are related 22.2 selection 22.3 keeping in mind Common myths about natural selection and adaptation 22.5 his chapter is about one of the great ideas in science: the theory of evolution by natural selection, formulated independently by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. The theory explains how T populations—individuals of the same species that live in the same area at the same time—have come to be adapted to environments ranging from arctic tundra to tropical wet forest. It revealed one of the five key attributes of life: Populations of organisms evolve. In other words, the heritable characteris- This chapter is part of the tics of populations change over time (Chapter 1). Big Picture. See how on Evolution by natural selection is one of the best supported and most important theories in the history pages 516–517. of scientific research. -

Microevolution and the Genetics of Populations Microevolution Refers to Varieties Within a Given Type

Chapter 8: Evolution Lesson 8.3: Microevolution and the Genetics of Populations Microevolution refers to varieties within a given type. Change happens within a group, but the descendant is clearly of the same type as the ancestor. This might better be called variation, or adaptation, but the changes are "horizontal" in effect, not "vertical." Such changes might be accomplished by "natural selection," in which a trait within the present variety is selected as the best for a given set of conditions, or accomplished by "artificial selection," such as when dog breeders produce a new breed of dog. Lesson Objectives ● Distinguish what is microevolution and how it affects changes in populations. ● Define gene pool, and explain how to calculate allele frequencies. ● State the Hardy-Weinberg theorem ● Identify the five forces of evolution. Vocabulary ● adaptive radiation ● gene pool ● migration ● allele frequency ● genetic drift ● mutation ● artificial selection ● Hardy-Weinberg theorem ● natural selection ● directional selection ● macroevolution ● population genetics ● disruptive selection ● microevolution ● stabilizing selection ● gene flow Introduction Darwin knew that heritable variations are needed for evolution to occur. However, he knew nothing about Mendel’s laws of genetics. Mendel’s laws were rediscovered in the early 1900s. Only then could scientists fully understand the process of evolution. Microevolution is how individual traits within a population change over time. In order for a population to change, some things must be assumed to be true. In other words, there must be some sort of process happening that causes microevolution. The five ways alleles within a population change over time are natural selection, migration (gene flow), mating, mutations, or genetic drift. -

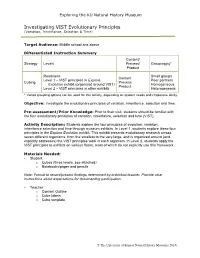

Investigating VIST Evolutionary Principles (Variation, Inheritance, Selection & Time)

Exploring the KU Natural History Museum Investigating VIST Evolutionary Principles (Variation, Inheritance, Selection & Time) Target Audience: Middle school and above Differentiated Instruction Summary Content/ Strategy Levels Process/ Grouping(s)* Product Readiness Small groups Content Level 1 – VIST principles in Explore Peer partners Cubing Process Evolution exhibit (organized around VIST) Homogeneous Product Level 2 – VIST principles in other exhibits Heterogeneous * Varied grouping options can be used for this activity, depending on student needs and chaperone ability. Objective: Investigate the evolutionary principles of variation, inheritance, selection and time. Pre-assessment/Prior Knowledge: Prior to their visit, students should be familiar with the four evolutionary principles of variation, inheritance, selection and time (VIST). Activity Description: Students explore the four principles of evolution: variation, inheritance selection and time through museum exhibits. In Level 1, students explore these four principles in the Explore Evolution exhibit. This exhibit presents evolutionary research across seven different organisms, from the smallest to the very large, and is organized around (and explicitly addresses) the VIST principles work in each organism. In Level 2, students apply the VIST principles to exhibits on various floors, most of which do not explicitly use this framework. Materials Needed: • Student o Cubes (three levels, see attached) o Notebooks/paper and pencils Note: Format to record/present findings determined by individual teacher. Provide clear instructions about expectations for documenting participation. • Teacher o Content Outline o Cube labels o Cube template © The University of Kansas Natural History Museum (2014) Exploring the KU Natural History Museum Content: VIST* Overview There are four principles at work in evolution—variation, inheritance, selection and time. -

Comparative Methods Offer Powerful Insights Into Social Evolution in Bees Sarah Kocher, Robert Paxton

Comparative methods offer powerful insights into social evolution in bees Sarah Kocher, Robert Paxton To cite this version: Sarah Kocher, Robert Paxton. Comparative methods offer powerful insights into social evolution in bees. Apidologie, Springer Verlag, 2014, 45 (3), pp.289-305. 10.1007/s13592-014-0268-3. hal- 01234748 HAL Id: hal-01234748 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01234748 Submitted on 27 Nov 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Apidologie (2014) 45:289–305 Review article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France, 2014 DOI: 10.1007/s13592-014-0268-3 Comparative methods offer powerful insights into social evolution in bees 1 2 Sarah D. KOCHER , Robert J. PAXTON 1Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA 2Institute for Biology, Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany Received 9 September 2013 – Revised 8 December 2013 – Accepted 2 January 2014 Abstract – Bees are excellent models for studying the evolution of sociality. While most species are solitary, many form social groups. The most complex form of social behavior, eusociality, has arisen independently four times within the bees. -

James K. Wetterer

James K. Wetterer Wilkes Honors College, Florida Atlantic University 5353 Parkside Drive, Jupiter, FL 33458 Phone: (561) 799-8648; FAX: (561) 799-8602; e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON, Seattle, WA, 9/83 - 8/88 Ph.D., Zoology: Ecology and Evolution; Advisor: Gordon H. Orians. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY, East Lansing, MI, 9/81 - 9/83 M.S., Zoology: Ecology; Advisors: Earl E. Werner and Donald J. Hall. CORNELL UNIVERSITY, Ithaca, NY, 9/76 - 5/79 A.B., Biology: Ecology and Systematics. UNIVERSITÉ DE PARIS III, France, 1/78 - 5/78 Semester abroad: courses in theater, literature, and history of art. WORK EXPERIENCE FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY, Wilkes Honors College 8/04 - present: Professor 7/98 - 7/04: Associate Professor Teaching: Biodiversity, Principles of Ecology, Behavioral Ecology, Human Ecology, Environmental Studies, Tropical Ecology, Field Biology, Life Science, and Scientific Writing 9/03 - 1/04 & 5/04 - 8/04: Fulbright Scholar; Ants of Trinidad and Tobago COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, Department of Earth and Environmental Science 7/96 - 6/98: Assistant Professor Teaching: Community Ecology, Behavioral Ecology, and Tropical Ecology WHEATON COLLEGE, Department of Biology 8/94 - 6/96: Visiting Assistant Professor Teaching: General Ecology and Introductory Biology HARVARD UNIVERSITY, Museum of Comparative Zoology 8/91- 6/94: Post-doctoral Fellow; Behavior, ecology, and evolution of fungus-growing ants Advisors: Edward O. Wilson, Naomi Pierce, and Richard Lewontin 9/95 - 1/96: Teaching: Ethology PRINCETON UNIVERSITY, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology 7/89 - 7/91: Research Associate; Ecology and evolution of leaf-cutting ants Advisor: Stephen Hubbell 1/91 - 5/91: Teaching: Tropical Ecology, Introduction to the Scientific Method VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY, Department of Psychology 9/88 - 7/89: Post-doctoral Fellow; Visual psychophysics of fish and horseshoe crabs Advisor: Maureen K. -

Introduction:Thinking Through Sociality

Thinking through Sociality THINKING THROUGH SOCIALITY An Anthropological Interrogation of Key Concepts Edited by _ Vered Amit Published in 2015 by Berghahn Books www.berghahnbooks.com © 2015 Vered Amit All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Amit, Vered, 1955- Thinking through sociality : an anthropological interrogation of key concepts / edited by Vered Amit. pages cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-78238-585-1 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-78238-586-8 (ebook) 1. Ethnology. 2. Social interaction. 3. Anthropology. I. Title. GN325.A44 2015 302--dc23 2014033522 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78238-585-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-78238-586-8 (ebook) Contents Acknowledgements vi _ Introduction Thinking through Sociality: The Importance of 1 Mid-level Concepts Vered Amit with Sally Anderson, Virginia Caputo, John Postill, Deborah Reed-Danahay and Gabriela Vargas-Cetina 1 Disjuncture: The Creativity of, and Breaks in, Everyday 21 Associations and Routines Vered Amit 2 Fields: Dynamic Configurations of Practices, Games and 47 Socialities John Postill 3 Social Space: Distance, Proximity -

The Impact of Darwinism on Sociology

Chapter 1, pp. 9-25, in Heinz-Juergen Niedenzu, Tamas Meleghy, and Peter Meyer, eds., The New Evolutionary Social Science: Human Nature, Social Behavior, and Social Change. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers, 2008. THE IMPACT OF DARWINISM ON SOCIOLOGY An Historical and Critical Overview Stephen K. Sanderson INTRODUCTION What has been the relationship between the social sciences, sociology in particular, and Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection? In a famous statement, Darwin said that the theory of natural selection would “lead psychology to be based on a new foundation.” In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, some social scientists followed Darwin’s lead. In his book In Search of Human Nature: The Decline and Revival of Darwinism in American Social Thought, the historian Carl Degler (1991) shows that at this early point in the development of the social sciences Darwinism was highly regarded by social scientists, and biology was considered a major underpinning of human behavior. In sociology, the lead was clearly taken in the most emphatic way by Edward Westermarck, a Finnish sociologist who became a major figure in both Finnish and British sociology. In the second volume of his three-volume The History of Human Marriage, Westermarck (1922b) developed the hypothesis on the origin of incest avoidance and exogamy for which he is today most famous, the “familiarity breeds indifference” theory. Westermarck argued that children brought up in close physical contact with each other in the early years of life would acquire a mutual sexual aversion, an emotion that had evolved by natural 9 10 Stephen K. -

Information Systems Theorizing Based on Evolutionary Psychology: an Interdisciplinary Review and Theory Integration Framework1

Kock/IS Theorizing Based on Evolutionary Psychology THEORY AND REVIEW INFORMATION SYSTEMS THEORIZING BASED ON EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY REVIEW AND THEORY INTEGRATION FRAMEWORK1 By: Ned Kock on one evolutionary information systems theory—media Division of International Business and Technology naturalness theory—previously developed as an alternative to Studies media richness theory, and one non-evolutionary information Texas A&M International University systems theory, channel expansion theory. 5201 University Boulevard Laredo, TX 78041 Keywords: Information systems, evolutionary psychology, U.S.A. theory development, media richness theory, media naturalness [email protected] theory, channel expansion theory Abstract Introduction Evolutionary psychology holds great promise as one of the possible pillars on which information systems theorizing can While information systems as a distinct area of research has take place. Arguably, evolutionary psychology can provide the potential to be a reference for other disciplines, it is the key to many counterintuitive predictions of behavior reasonable to argue that information systems theorizing can toward technology, because many of the evolved instincts that benefit from fresh new insights from other fields of inquiry, influence our behavior are below our level of conscious which may in turn enhance even more the reference potential awareness; often those instincts lead to behavioral responses of information systems (Baskerville and Myers 2002). After that are not self-evident. This paper provides a discussion of all, to be influential in other disciplines, information systems information systems theorizing based on evolutionary psych- research should address problems that are perceived as rele- ology, centered on key human evolution and evolutionary vant by scholars in those disciplines and in ways that are genetics concepts and notions.