Persian Architecture and Mathematics: an Overview Persian Architecture Has Long Been Known As the Embodiment of Mathematical and Geometrical Premises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study the Status Column Element in the Achaemenid Architecture and Its

Special Issue INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND January 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Study the status column element in the Achaemenid architecture and its effect on India architecture (comparrative research of persepolis columns on pataly putra columns in India) Dr. Amir Akbari* Faculty of History, Bojnourd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bojnourd, Iran * Corresponding Author Fariba Amini Department of Architecture, Bukan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bukan, Iran Elham Jafari Department of Architecture, Khoy Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khoy, Iran Abstract In the southern region of Iran and the north of persian Gulf, the state was located in the ancient times was called "pars", since the beginning of the Islamic era its center was shiraz. In this region of Iran a dynasty called Achaemenid came to power and could govern on the very important part of the worlds for years. Achaemenid exploited the skills of artists and craftsman countries under its command. In this sense, in Architecture works and the industry this period is been seen the influence of other nations. Achaemenid kings started to build large and beautiful palaces in the unter of their government and after 25 centuries, the remnants of which still remain firm and after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire by Grecian Alexander in India. The greatest king of India dynasty Muryya, was called Ashoka the grands of Chandra Gupta. The Ashoka palace that id located at the putra pataly around panta town in the state of Bihar in North east India. Is an evidence of the influence of Achaemenid culture in ancient India. The similarity of this city and Ashoka Hall with Apadana Hall in Persepolis in such way that has called it a india persepolis set. -

Qutb Minar: Religion and Power in 13Th-Century India Professor Munis Faruqui (Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies, UC Berkeley)

The Making of a Modern Myth Qutb Minar: Religion and Power in 13th-Century India Professor Munis Faruqui (Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies, UC Berkeley) I. Introduction India is the world’s largest democracy, and has the world’s second largest population of Muslims. Over the last few decades, deep religious divisions have appeared between the Hindu majority and the Muslim minority, who comprise 12–15 percent of the population. Extremists in either community have stoked violent religious conflict in ways that will be discussed shortly. Most of the violence in recent history has occurred in the form of pogroms. Most of the victims are Muslims. There are at least two critical threads that link contemporary anti-Muslim violence: first, a rising tide of Hindu nationalism. Second, much of the violence has been continuously stoked by rhetoricians’ use of an exaggerated and distorted history of endless conflict between these two groups—especially during the period when Muslim political authorities dominated northern India (c. 1200–1750). According to Hindu nationalists, the experience under the Muslims was oppressive, the Muslim rulers tyrannical, Hindu temples were destroyed, and so on. So the current anti- Muslim pogroms are payback, as the more extreme elements among the Hindu nationalists openly assert: attacking Muslims today is thus justified for what happened 500, 600, or 700 years ago. Like many groups elsewhere in the world, Hindu nationalists invoke history. Irish Republicanism invokes battles that happened in 1690 and so on. Groups in the Balkans are another example: Serbs, Croats, and Bosniacs have their own histories, and the 1389 battle of Kosovo becomes a central rallying cry for Serbian nationalism. -

Simulating Self Supporting Structures

Simulating Self Supporting Structures A Comparison study of Interlocking Wave Jointed Geometry using Finite Element and Physical Modelling Methods Shayani Fernando1, Dagmar Reinhardt2, Simon Weir3 1,2,3University of Sydney, Australia 1,2,3{shayani.fernando|dagmar.reinhardt|simon.weir}@sydney.edu.au Self-supporting modular block systems of stone or masonry architecture are amongst ancient building techniques that survived unchanged for centuries. The control over geometry and structural performance of arches, domes and vaults continues to be exemplary and structural integrity is analysed through analogue and virtual simulation methods. With the advancement of computational tools and software development, finite and discrete element modeling have become efficient practices for analysing aspects for economy, tolerances and safety of stone masonry structures. This paper compares methods of structural simulation and analysis of an arch based on an interlocking wave joint assembly. As an extension of standard planar brick or stone modules, two specific geometry variations of catenary and sinusoidal curvature are investigated and simulated in a comparison of physical compression tests and finite element analysis methods. This is in order to test the stress performance and resilience provided by three-dimensional joints respectively through their capacity to resist vertical compression, as well as torsion and shear forces. The research reports on the threshold for maximum sinusoidal curvature evidenced by structural failure in physical modelling methods and finite element analysis. Keywords: Mortar-less, Interlocking, Structures, Finite Element Modelling, Models INTRODUCTION / CONTEXT OF RESEARCH used, consideration of relative position of each block Self-supporting stone or masonry architecture is the within the overall geometry, and joints of a block as- arrangement of modular elements that are struc- sembly become the driving factor that determine the turally performative and hold together through ver- architecture. -

2020.06.04 Lecture Notes 10Am Lecture 3 – Estereostàtic (Stereostatic: Solid + Force of Weight Without Motion)

2020.06.04 Lecture Notes 10am Lecture 3 – Estereostàtic (stereostatic: solid + force of weight without motion) Welcome back to Antoni Gaudí’s Influence on the Contemporary Architecture of Barcelona and Bilbao. Housekeeping Items for New Students: Muting everyone (background noise) Questions > Raise Hand & Chat questions to Erin (co-host). 5 to 10 minute break & 10 to 15 minutes at end for Q&A 2x (Calvet chair) Last week, 1898 same time Gaudí’s finishing cast figures of the Nativity Façade. Started construction on Casa Calvet (1898-1900) influence of skeletons on chair, bones as props/levers for body movement, develops natural compound curved form. Gaudí was turning toward nature for inspiration on structure and design. He studied the growth and patterns of flowers, seeds, grass reeds, but most of all the human skeleton, their form both functional and aesthetic. He said, these natural forms made up of “paraboloids, hyperboloids and helicoids, constantly varying the incidence of the light, are rich in matrices themselves, which make ornamentation and even modeling unnecessary.” 1x (Calvet stair) Traditional Catalan method of brickwork vaulting (Bóvedas Tabicadas), artform in stairways, often supported by only one wall, the other side open to the center. Complexity of such stairs required specialist stairway builders (escaleristas), who obtained the curve for the staircase vaults by hanging a chain from two ends and then inverting this form as a guide for laying the bricks to the arch profile. 1x (Vizcaya bridge) 10:15 Of these ruled geometries, one that he had studied in architectural school, was the catenary curve: profile resulting from a cable hanging under its own weight (uniformly applied load)., which five years earlier used for the Vizcaya Bridge, west of Bilbao (1893), suspension steel truss. -

The Quandary of Assessing Faculty Performance K

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Faculty Publications 1-1-2013 The Quandary of Assessing Faculty Performance K. Fatehi Kennesaw State University, [email protected] M. Sharifi California State University J. Herbert Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/facpubs Part of the Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods Commons Recommended Citation Fatehi, K., Sharifi, M., Herbert, J. (2013). The Quandary of Assessing Faculty Performance. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 13(3/4) 2013, 72-84. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Quandary of Assessing Faculty Performance Kamal Fatehi Kennesaw State University Mohsen Sharifi California State University, Fullerton Jim Herbert Kennesaw State University Many educators assert that the continued use of student ratings of teaching effectiveness does not improve learning in the long run. However, administrators continue to use student opinions regarding teaching effectiveness because of its convenience and the quantitative nature of the measurement. Reducing a very complex phenomenon to a very simple numeral has its appeal. In this paper we discuss a related aspect of teaching assessment, namely the variations of skills among instructors and the students’ response to the same. In doing so, we suggest pragmatic guidelines to university administrators for evaluating various levels of skills and performance. INTRODUCTION At many universities, student evaluation of teaching is a significant part of faculty member’s performance evaluation. -

Decoding Geometry, Proportions and Its Relationship with Aesthetics in Traditional Iranian Architecture

Original Article Decoding geometry, proportions and its relationship with aesthetics in traditional Iranian architecture Shayan Mahmoudi *, Ali Rezvani, Seyed Alireza Hosseini Vahdat Bachelor degree in Architecture, Shahid Beheshti Technical and Vocational Junior College, Karaj Branch, Department of Art and Architecture, Karaj, Iran. Abstract Certain proportions can be observed in creation and design of nature various forms. These proportions are geometrical relationships that are immaterial in origin and follow the spiritual and supernatural principles of their subject sacredness and have symbolic language and spiritual characteristics. Geometry was inseparable from other four Pythagorean sciences in traditional world, including geometric relationships, arithmetic (number), music and astronomy. We always need geometry knowledge in order to construct a building from first steps to final steps. Using proportions is particularly important because of creating visual aesthetic in visual and architectural arts, and almost all artworks are based on some form of proportion. This research tries to decode the work and find the aim and true purpose of its creator in responding the hypothesis that architect knowledge of geometry and his creative use facilitates the conversion of concept into space and form in designing process and minimizes concept erosion of process through studying architecture, geometry and existing proportions. The results obtained from library and field studies by descriptive-analytical method show that different proportions -

Gundeshapur, Centro De La Cultura Científica Medieval Por Josep Lluís Barona

[Historias de ciencia] Gundeshapur, centro de la cultura científica medieval por Josep Lluís Barona i la Biblioteca y el Museo de Alejandría fueron instituciones importantes para el cultivo de las ciencias en la Antigüedad, Gundeshapur fue el «Bajo el dominio del monarca Smayor centro intelectual medieval. Se encontraba en la sasánida Cosroes I, Gundeshapur actual provincia de Juzestán, en el suroeste de Irán. Dice la tradición que Sapor I, hijo de Artajerjes, fundó adquirió el máximo prestigio la ciudad, después de derrotar al ejército romano, como centro cultural, científico como una guarnición para los prisioneros de guerra y artístico» romanos. Con el paso del tiempo Gundeshapur se con- virtió en un cruce de culturas. Sapor I se casó con la hija del emperador romano Aureliano, e hizo de Gun- y medicina, y obras chinas de botánica y filosofía deshapur la capital de Persia, donde fundó un hospital natural. Se cree que Borzuya hizo la traducción al persa y llevó a médicos griegos para practicar y enseñar del texto indio Panchatantra, colección antigua de fábu- la medicina hipocrática. La ciudad contaba también las hindúes sobre la naturaleza escritas en sánscrito. con una gran biblioteca y un centro de enseñanza La dinastía sasánida fue derrotada por los ejércitos de las artes y las ciencias. musulmanes en 638. La Academia de Gundesha- Cuando, en 489, el centro teológico y científico pur pervivió dos siglos, transformada en un centro nestoriano de Edesa fue clausurado por el emperador islámico para el cultivo y aprendizaje de las ciencias, bizantino, los científicos, filósofos y médicos se tras- las artes y la medicina. -

Tourist Agency

Homa Travel Agency Introduction This project concerns to create a travel agency. The main office is located in the Frankfurt Airport and the second one would be in International IKA in Tehran. Homa agency offers sightseeing package tours to customers providing travel related products and services to Iran. Iran has an area of 1 ,648 ,195 square kilometers and is the 17th largest country in the world. The population is over 74 million (2010 census). Iran has a dry climate with low rainfall. Winter (December to February) can be very cold in most parts of the country , while in summer (June – August) temperatures of 40 degrees Celsius are not uncommon. Spring (March – May) and autumn (September – November) are ideal times to visit Iran. Tehran is the capital of Iran which has the population of about 17 million. The most famous tourist cities of Iran: Tehran Isfahan Shiraz Tabriz Kish Island Yazd Kerman Tehran It has been Iran's capital for over 200 years. With nearly 9 million inhabitants Tehran Province is Iran's most densely populated province. Tehran is a city of four seasons, with hot summers, freezing winters, and brief spring and autumn. Milad tower Milad tower with the height of 435m is the 4th tallest tower in the world after CN tower (in Toronto), Ostankino tower (in Moscow) and Oriental pearl tower (in Shanghai) and also 12th tallest freestanding structure in the world. Shiraz Shiraz is known as the city of poets, wine and flowers. It is a major tourist destination in Iran which attracts tourists from all over the world. -

A Vivid Research on Gundīshāpūr Academy, the Birthplace of the Scholars and Physicians Endowed with Scientific and Laudable Q

SSRG International Journal of Humanities and Soial Science (SSRG-IJHSS) – Volume 7 Issue 5 – Sep - Oct 2020 A Vivid Research on Gundīshāpūr Academy, the Birthplace of the Scholars and Physicians Endowed with Scientific and laudable qualities Mahmoud Abbasi1, Nāsir pūyān (Nasser Pouyan)2 Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Medical Ethics and Law Research Center, Tehran, Iran. Abstract: Iran also known as Persia, like its neighbor Iraq, can be studied as ancient civilization or a modern nation. Ac- cording to Iranian mythology King Jamshīd introduced to his people the science of medicine and the arts and crafts. Before the establishment of Gundīshāpūr Academy, medical and semi-medical practices were exclusively the profession of a spe- cial group of physicians who belonged to the highest rank of the social classes. The Zoroastrian clergymen studied both theology and medicine and were called Atrāvān. Three types physicians were graduated from the existing medical schools of Hamedan, Ray and Perspolis. Under the Sasanid dynasty Gundīshāpūr Academy was founded in Gundīshāpūr city which became the most important medical center during the 6th and 7th century. Under Muslim rule, at Bayt al-Ḥikma the systematic methods of Gundīshāpūr Academy and its ethical rules and regulations were emulated and it was stuffed with the graduates of the Academy. Finally, al-Muqaddasī (c.391/1000) described it as failing into ruins. Under the Pahlavī dynasty and Islamic Republic of Iran, the heritage of Gundīshāpūr Academy has been memorized by founding Ahwaz Jundīshāpūr University of Medical Sciences. Keywords: Gundīshāpūr Academy, medical school, teaching hospital, Bayt al-Ḥikma, Ahwaz Jundīshāpūr University of Medical Science, and Medical ethics. -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

Abstracts Electronic Edition

Societas Iranologica Europaea Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the State Hermitage Museum Russian Academy of Sciences Abstracts Electronic Edition Saint-Petersburg 2015 http://ecis8.orientalstudies.ru/ Eighth European Conference of Iranian Studies. Abstracts CONTENTS 1. Abstracts alphabeticized by author(s) 3 A 3 B 12 C 20 D 26 E 28 F 30 G 33 H 40 I 45 J 48 K 50 L 64 M 68 N 84 O 87 P 89 R 95 S 103 T 115 V 120 W 125 Y 126 Z 130 2. Descriptions of special panels 134 3. Grouping according to timeframe, field, geographical region and special panels 138 Old Iranian 138 Middle Iranian 139 Classical Middle Ages 141 Pre-modern and Modern Periods 144 Contemporary Studies 146 Special panels 147 4. List of participants of the conference 150 2 Eighth European Conference of Iranian Studies. Abstracts Javad Abbasi Saint-Petersburg from the Perspective of Iranian Itineraries in 19th century Iran and Russia had critical and challenging relations in 19th century, well known by war, occupation and interfere from Russian side. Meantime 19th century was the era of Iranian’s involvement in European modernism and their curiosity for exploring new world. Consequently many Iranians, as official agents or explorers, traveled to Europe and Russia, including San Petersburg. Writing their itineraries, these travelers left behind a wealthy literature about their observations and considerations. San Petersburg, as the capital city of Russian Empire and also as a desirable station for travelers, was one of the most important destination for these itinerary writers. The focus of present paper is on the descriptions of these travelers about the features of San Petersburg in a comparative perspective. -

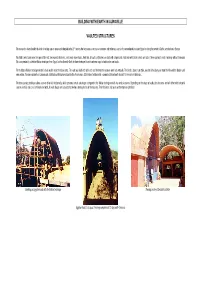

Building with Earth in Auroville Vaulted Structures

BUILDING WITH EARTH IN AUROVILLE VAULTED STRUCTURES The research in Auroville with this kind of roofing aims to revive and integrate in the 21st century the techniques used in past centuries and millennia, such as those developed in ancient Egypt or during the period of Gothic architecture in Europe. This R&D seeks to increase the span of the roof, decrease its thickness, and create new shapes. Note that all vaults and domes are built with compressed stabilised earth blocks which are laid in “Free spanning” mode, meaning without formwork. This was previously called the Nubian technique, from Egypt, but the Auroville Earth Institute developed it and found new ways to build arches and vaults. The traditional Nubian technique needed a back wall to stick the blocks onto. The vault was built arch after arch and therefore the courses were laid vertically. The binder, about 1 cm thick, was the silty-clayey soil from the Nile and the blocks used were adobe. The even regularity of compressed stabilised earth block produced by the Auram press 3000 allows building with a cement-stabilised earth glue of 1-2 mm only in thickness. The free spanning technique allows courses to be laid horizontally, which presents certain advantages compared to the Nubian technique which has vertical courses. Depending on the shape of vaults, the structures are built either with horizontal courses, vertical ones or a combination of both. All vault shapes are calculated to develop catenary forces in the masonry. Their thickness and span can therefore be optimised. Building