A Consumer Behaviour Analysis of Hedonic Consumption As Related to the Harley-Davidson Brand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TV Listings FRIDAY, MAY 5, 2017

TV listings FRIDAY, MAY 5, 2017 14:55 The Zhuzhus 05:45 Loopdidoo 16:00 Itʼs Not Rocket Science 15:45 Elena Of Avalor 06:00 Zou 16:55 Surprise Surprise 16:10 Liv And Maddie 06:15 Calimero 17:50 Coach Trip 16:35 Teen Beach 2 06:30 Loopdidoo 18:45 Emmerdale 18:25 Alex & Co. 06:45 Henry Hugglemonster 19:45 Coronation Street 18:50 Best Friends Whenever 07:00 My Friends Tigger & Pooh 20:10 Guess This House 00:20 Street Outlaws 19:15 Tsum Tsum Shorts 07:25 Sofia The First 21:00 Itʼs Not Rocket Science 01:10 What On Earth? 00:00 Binny And The Ghost 19:20 Binny And The Ghost 07:50 The Lion Guard 06:00 Gravity Falls 00:25 Hank Zipzer 21:55 Surprise Surprise 02:00 Sydney Harbour 19:45 Austin & Ally 08:15 PJ Masks 06:25 Star vs The Forces Of Evil 22:50 Emmerdale 02:50 Todd Sampsonʼs Body Hack 00:45 The Hive 20:10 Jessie 08:40 Jake And The Never Land 06:50 Penn Zero: Part Time Hero 00:50 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 23:15 Emmerdale 03:40 Fast Nʼ Loud 20:35 Cracke Pirates 07:15 Milo Murphyʼs Law Witch 04:30 Storage Hunters UK 20:40 Disney The Lodge 09:05 Goldie & Bear 07:25 Danger Mouse 05:00 How Do They Do It? 01:40 Hank Zipzer 21:05 Girl Meets World 09:35 The Lion Guard 02:05 Binny And The Ghost 07:40 Supa Strikas 05:30 How Do They Do It? 21:30 Thatʼs So Raven 10:00 Sofia The First 08:05 Two More Eggs 02:55 Hank Zipzer 21:55 Star Darlings 10:30 Doc McStuffins 06:00 Worldʼs Top 5 03:15 The Hive 08:10 K.C. -

Washington Ballet Theater Brings the Dance to Pe

Serving our communities since 1889 — www.chronline.com Tractor $1 Early Week Edition Parade Hits Tuesday, Centralia / Dec. 13, 2016 Life 1 Christmas Light Display For Suicide Awareness Fort Borst Light Show Playing Host to Santa Packwood Woman Honored After Channeling Claus as Annual Light Tour Returns / Main 10 Grief to Help Others, Form State Law / Main 3 Report: Man Impersonates Police Officer, Gropes Woman By The Chronicle who allegedly stopped a woman assault by a person dressed as a uniform driving an older- The police impersonator Centralia Police detectives and groped her Sunday night in police officer in the 400 block of model Ford Crown Victoria then allegedly groped the victim. are investigating a report of a Centralia. South Gold Street in Centralia. with a single red light on its roof The woman reported she was man dressed as a police officer, At 7:53 p.m. on Sunday, The woman reported that stopped her vehicle and asked driving a police-model vehicle police received a report of an a white male in a police-type her to take a sobriety test. please see POLICE, page Main 14 New Fees Coming Washington Ballet Theater for County Services Brings the Dance to Pe Ell By The Chronicle Fees at the Lewis County TIS THE SEASON: ‘The department Public Health Nutcracker’ Comes to and Social Services were increased at Monday’s county West Lewis County commissioners meeting. to Acclaim From The departments of Participants, Attendees Community Development and Public Works were also By Lisa Brunette reviewed but there were For The Chronicle no increases. -

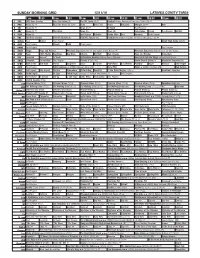

Sunday Morning Grid 12/11/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/11/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Denver Broncos at Tennessee Titans. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Give (TVY) Heart Naturally Shotgun (N) Å Golf 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Washington Redskins at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Small Town Santa (2014) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Magic Hugs and Knishes American Experience The life and legacy of Walt Disney. Å American Experience Walt Disney’s life and legacy. 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ New Orleans Hugs and Knishes Carpenters 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch A Christmas Reunion (2015) Denise Richards. How Sarah Got Her Wings (2015) Derek Theler. 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Planeta U (N) (TVY) Como Dice el Dicho (N) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Baby Geniuses › (1999) Kathleen Turner. -

Cablefax Dailytm Tuesday — November 7, 2017 What the Industry Reads First Volume 28 / No

www.cablefaxdaily.com, Published by Access Intelligence, LLC, Tel: 301-354-2101 Cablefax DailyTM Tuesday — November 7, 2017 What the Industry Reads First Volume 28 / No. 214 Full Monty: Altice’s MVNO with Sprint Sets It Apart from Peers in Wireless Given that Altice is a wireless player in every other market it operates in, the cable provider’s foray into the US mobile market was inevitable. The wheels are now in motion, with the company announcing a full MVNO partner- ship with Sprint that gives Altice access to the carrier’s wireless network. Altice isn’t the first US operator to delve into the mobile space; Comcast already has more than 250K Xfinity Mobile subs via an MVNO deal with Veri- zon, and Charter plans to launch its service via the same Verizon MVNO next year. Altice’s “full MVNO” approach, however, sets it apart from its US peers. Besen Group CEO Alex Besen, whose firm advises clients in the MVNO space, explained that Altice will have greater control over its wireless offering than either Comcast or Charter, who are simply resellers. “If Verizon, for example, introduces voice-over-IP or WiFi calling, then Charter and Comcast get it,” Besen said. “In the case of Sprint and Altice, Altice has a full MVNO, so they don’t have to depend on Sprint’s network. They can say, ‘Hey. We want to introduce the WiFi calling today,’ and they can do it. Verizon’s agreement with Comcast and Charter doesn’t allow them to do that. That’s why today you don’t see Xfinity Mobile having WiFi calling feature.” Besen also said Sprint has the most competitive wholesale pricing, meaning Altice will be able to offer its mobile service at higher margins. -

Two Christmas Gifts for One Price!

PAID ECRWSS Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL Hardware Saturday, Saturday, Dec. 10, 2016 10, Dec. (715) 479-4421 AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS As we celebrate the message of that very first Noel, we wish you and your family great joy this holiday season. A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW THE VILAS COUNTY SECTION OF SPECIAL A Goodwill Toward All Mankind – Goodwill Toward • Automotive Supplies • Keys Duplicated Cleaning • Open 7 days a week to serve you 606 E. Wall, Eagle River 715-479-4496 606 E. Wall, • Vast Battery Selection • Plumbing & Electrical Supplies Fixtures • Vast peace on earth Depend on the people at Nelson’s for all your needs. Depend on the people at Nelson’s and Heartfelt Thanks to our Neighbors & Friends! and Heartfelt Nelson’s • Hallmark Cards • Lawn & Garden Supplies • Hand & Power Tools • Propane Filling • Hallmark Cards Lawn & Garden Supplies Hand Power Tools ACE IS THE PLACE ACE NORTH WOODS NORTH THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING WOODS OF NORTH BUNYAN THE PAUL © Eagle River Publications, Inc. 1972 Inc. Publications, TwoTwo ChristmasChristmas GiftsGifts forfor OneOne Price!Price! Take a new subscription or new gift subscription for one year and receive a A WILDLIFE COLLECTION FREE BOOK – By Kurt L. Krueger $55* Subscription – Free $4040 BookBook $ $ (Add an additional $5 for postage of book if mailed) One Section Rest of Wisconsin — • Out-of-state — Judged as VILAS COUNTY 63 75 Wisconsin’s *In Vilas and Oneida counties. Book offer also available downstate and out-of-state. -

Kuwait Times 2-10-2017.Qxp Layout 1

MUHARRAM 12, 1439 AH MONDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2017 Max 43º 32 Pages 150 Fils Established 1961 Min 24º ISSUE NO: 17344 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Amir congratulates PM on Violence erupts as Catalans 2 women stabbed to death Barcelona win behind closed 2 Kuwait bourse’s promotion 6 vote on split from Spain 8 in Marseille knife attack 16 doors amid Catalonia clashes Gulf states say goodbye to tax-free reputation UAE doubles tobacco prices, hikes soft drink prices by 50% DUBAI: Hard hit by a drop in oil income, energy-rich Gulf balance sheets have remained in the red despite government states will next year introduce value-added tax to a region long austerity measures recommended by the International known for being tax-free. Some have hailed introducing VAT as Monetary Fund, including freezing wages, benefits and state- the start of “exciting, dramatic” change in the region, but the funded projects, cutting subsidies and raising power and fuel measure is also expected to push prices up for all residents prices. Governments across the region have also drawn hun- including citizens and low- dreds of billions of dollars from income workers. Yesterday, the their massive sovereign wealth United Arab Emirates doubled resources in an attempt to curb the price of tobacco and the deficit. increased soft drink prices by The six states are now taking 50 percent, ahead of the more Future looks austerity measures a step further general VAT on goods and with the plan to introduce VAT, services from Jan 1. daunting for ending their decades-old repu- The UAE is one of the six tation for being tax havens. -

KT 1-5-2017.Qxp Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION MONDAY, MAY 1, 2017 SHABAN 05, 1438 AH www.kuwaittimes.net E-media, youth Merkel in Saudi Alli, Kane earn Major theme of to hold talks Spurs stirring Kuwait 2forum on refugees8 derby20 win Kuwaiti businessman Min 29 º Max 40º High Tide shot dead in Istanbul 03:55 & 14:31 Low Tide Iran satellite TV head also killed in armed attack 06:57 & 19:33 40 PAGES NO: 17214 150 FILS KUWAIT/ISTANBUL: A Kuwaiti businessman was shot Investigate fish dead in Istanbul late Saturday together with his Iranian business partner. The citizen Mohammad Metab Al- Shalahi was shot dead in an armed attack on his car as death, alleged he was in the company of the Iranian resident in Turkey. Kuwaiti Consul in Istanbul Mohammed Al- FIFA bribes: MPs Mohammed confirmed the death of the citizen. In a press statement, Mohammad said that the consulate in By B Izzak Istanbul is closely monitoring the situation and follow- ing up investigations into the killing of the Kuwaiti citi- KUWAIT: Three main issues dominated the local parlia- zen. It is also making necessary arrangements to repatri- mentary scene yesterday with MPs demanding investiga- ate his body to Kuwait. tions into the mass fish death and the allegations of Turkish security agencies have launched an inquiry Kuwait Football officials’ involvement in alleged graft. MPs to track down the killers and investigate the motive also called on authorities to take part in investigations to behind the crime. The citizen was reportedly in his four- uncover the killers who assassinated Kuwaiti business- wheel vehicle with his Iranian friend Saeed Karimian, a man Mohammad Metab Al-Shalahi in Istanbul Saturday member of the Iranian opposition who owns TV chan- night along with an Iranian Dubai-based TV owner and nels and other media outlets. -

Photo Gallery at Hours: Mon.-Fri

PAID ECRWSS % OFF Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL Sept. 3 Saturday, (in stock only) 11 a.m. - 1 p.m. 11 25 items) STARCRAFT Remote Live WHDG MAKE YOUR BEST DEAL! PONTOONS — clearance marked Winter Gear (Excludes helmets & SALES SERVICE RENTALS 5,650 6,995 $ $ 19,995 10,175 13,595 Saturday, Saturday, $ $ $ Sept. 3, 2016 3, Sept. (715) 479-4421 ...... AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS : Financing ................. ................. S READY TO RIDE TO READY as Low 3.99% SALES EVENT — L Rebates up to $2,000 Can Am Off Road Can A E ............................... D T E 2014 Sweetwater 2486 Mercuryw/115-HP ................... 2014 GTI SE 130 2015 GTI SE 155 2016 Defender HDS 2016 Commander 1000 XT A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW THE VILAS COUNTY SECTION OF SPECIAL A E www.tracksideinc.com L SALE — Financing Sea-Doo F YELLOW TAG ATV/UTV Pontoons as Low 3.99% L 6,500 7,495 7,495 4,500 5,250 Rebates up to $1,000 $ $ $ $ $ 9,995 .. A $ Personal Watercraft T ............ N E ....................... R ........................ ........................ Financing CLEARANCE — as Low 2.99% Rebates up to $2,000 Polaris Off Road FACTORY AUTHORIZED FACTORY 2013 GTI 130 2014 GTI 130 2015 ACE 570 2015 RZR 570 EPS 2016 Ranger Crew 570 4 2013 Sweetwater 2086 Mercury Big Footw/60-HP .......... 1651 HWY. 45 N • EAGLE RIVER, WI 54521 • (715) 479-2200 45 N • EAGLE RIVER, 1651 HWY. Located 1 Mile North of Eagle River on Hwy. 45 Located 1 Mile North of Eagle River on Hwy. -

25Jan2021 6032 Films

DVDjan03 1/25/2021 MOVIE_NAME WIDE_STDRD STAR1 STAR2 Jan25 2021 UpLd GoogleDrive 6032 add Dig Copies YouTube Vudu AMZ iTunes = moviesAn RR for railroad: SURF-separate; DG TRAV MUSIC AmzVidLib Pcar ELVIS DOC was pbs now most (500) day of summer BluRay Joseph Gordon-Levitt zooey deschanel 007 1962 Dr. No (part of james bond collection) sean connery / ursula andress joseph wiseman - dir: terrence 007 1963 From Russia with Love (james bond sean connery / dir: terrence yo 007 1964 Goldfinger james bond ultimate ed & sean connery / gert frobe honor blackman 007 1965 Thunderball 3bond BluRay collection BluR sean connery / adolfo celi claudine auger (domino) 007 1967 Casino Royale 1967 ($25 film collecti ws peter sellers / ursula andress david niven / woody allen 007 1967 You Only Live Twice (part of james b BluRay sean connery / donald pleasen 007 1969 on her majesty's secret service (part george lazenby / diana rigg telly tavalas 007 1971 Diamond are Forever james bond ulti BluR sean connery / jill st. john 007 1973 live and let die (part of james bond c roger moore / yaphet kotto jane seymour (mccartney & win 007 1974 man with the golden gun james bond roger moore / christopher lee britt ekland 007 1977 spy who loved me james bond ultima roger moore / barbara bach curt jurgens 007 1979 moonraker (part of james bond collec roger moore / lois charles michale lonsdale / richard kiel 007 1981 for your eyes only (part of james bon roger moore / carole bouquet topol 007 1983 ? never say never again (sean too ol ws non ca sean connery / klaus maria bra kim basinger / max van sylow 007 1983 octopussy (part of james bond collect roger moore / maud adams louis jourdan / kristina wayborn 007 1985 view to a kill james bond ultimate ed. -

Tv Serije Strane I Domaće

POPIS TV-SERIJA PO ABECEDNOM REDU - 01.09.2020. sve serije su titlovane na hrvatski jezik 1 11.22.63 2 12 Monkeys 3 13 Reasons Why 4 2 Broke Girls 5 24: Live Another Day 6 666 Park Avenue 7 9-1-1 8 A Christmas Carol - Božićna priča 9 A Discovery of Witches 10 A Million Little Things 11 A Series of Unfortunate Events 12 A to Z 13 A Very English Scandal 14 A Young Doctor's Notebook 15 A.D. The Bible Continues 16 About a Boy 17 Absentia 18 Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. 19 Alcatraz 20 ALF 21 Allegiance 22 Alo, Alo! ( 'Allo 'Allo! ) 23 Alphas 24 Altered Carbon 25 Amazing Stories 26 Amber 27 American Crime 28 American Crime Story 29 American Gods 30 American Gothic 31 American Horror Story 32 American Vandal 33 Ancient Aliens 34 Ancient X-Files 35 Angel from Hell 36 Anger Management - Kontrola bijesa 37 Angie Tribeca 38 Animal Kingdom 39 Animal Practice 40 Anne 41 Another Life 42 Aquarius 43 Arrow 44 Ascension 45 Ash vs Evil Dead 46 Atlanta 47 Awake 48 Babylon 5 49 Babylon Berlin 50 Back in the Game 51 Backstrom 52 Bad Teacher 53 Baghdad Central 54 Ballers 55 Band Of Brothers - Združena braća 56 Banished 57 Banshee 58 Baptiste 59 Barbarians Rising 60 Barkskins 61 Barry 62 Bates Motel 63 Battle Creek 64 Battlestar Galactica 65 BBC Alaska: Earth's Frozen Kingdom 66 BBC Hidden Kingdoms 67 BBC Life Story 68 Beauty and the Beast 69 Believe 70 Berlin Station 71 Better Call Saul 72 Better Things 73 Beware the Batman 74 Beyond 75 BH90210 - Beverly Hills 76 Big Little Lies - Velike male laži 77 Billion 78 Biohackers 79 Bitten 80 Black Box 81 Black Lightning -

Auctions 6 9 4 5 2 3 5 3 9 7 1 4 2 1 9 4 2 7 8 5 5 2 9 7 6 5 1 2 9 8 9

Deliver to addressee below, or CURRENT RESIDENT ECRWSS PRSRT STD US POSTAGE PAID WICHITA, KS PERMIT NO 441 LICATION FREE PUB Residential Customer / PO 115 S. Kansas, Haven, Kansas 67543-0485 620-465-4636 • www.ruralmessenger.com Vol. 13 No. 36 • October 18, 2017 “The strength of a nation derives from the integrity of the home.” –Confucious Pet Peeves Running Amuck! AUCTIONS 10/19/2017 - Auction Specialists - Bentley - Page21 1 5 2 9 I don’t have many pet peeves, but the few I do 10/20/2017 - JP Weigand Auction - Wichita - Page26 have occasionally jump the fence and run wild 10/20/2017 - Kaufman Auction - Stark City, MO - Page38 for a spell. One of those pet peeves involves a 10/20/2017 - Morris Yoder Auction - Hutchinson - Page36 6 9 10/21/2017 - Bob’s Auction Service - Hope - Page18 small group of outdoors men we kids used to call 10/21/2017 - Jack Newcom Auction - Augusta - Page37 “slob hunters.” You know, the ones that go afield 10/21/2017 - Korte Auction - Douglass - Page21 5 7 2 6 each hunting season only for the bragging rights 10/21/2017 - Morris Yoder Auction - Hutchinson - Page36 to having killed something. They shoot from their 10/21/2017 - Seedstock Plus - Carthage, MO - Page27 10/21/2017 - Younger Auction - Maryville, MO - Page11 5 3 1 4 9 pickup; they shoot from the road; they hunt after 10/25/2017 - Floyd Auction (2) - Kingman - Page23 hours without licenses (known as poaching) they 10/25/2017 - Riggin & Co Auction - Haven - Page16 shoot at any kind of sound and movement; they 10/26/2017 - R.E.I.B. -

Discovery Channel Ruge Con El Estreno De 'Harley and The

Home / Noticias / Discovery Channel ruge con el estreno de ‘Harley and The Davidsons’ Discovery Channel estrena hoy las 22,00 horas esta serie que retratará los orígenes de uno de los más reconocibles iconos estadounidenses: las míticas motocicletas Harley-Davidson fabricadas en Milwaukee Discovery Channel ha decidido dedicar su horario de máxima audiencia, desde el viernes 30 de septiembre hasta el domingo 2 de octubre, a investigar los orígenes de esta emblemática compañía. Los tres capítulos que componen la serie Harley and the Davidsons, que en EEUU también se emitieron en tres noches consecutivas, fueron seguidos por 4,4 millones de espectadores, convirtiéndose en el estreno más seguido de la televisión por cable en los últimos años. Harley and the Davidsons conmemora el nacimiento de esta moto icónica en el comienzo del siglo XX, un tiempo de profundos cambios sociales y tecnológicos. Walter, Arthur y Bill arriesgaron su fortuna y su estilo de vida para lanzar la inminente empresa. Walter, Arthur y Bill cimentaron una reputación de Harley Davidson como constructores de una moto que llega a todas partes, se puede montar salvajemente e ignorar las normas establecidas. Es un legado que ha durado más de 100 años, asentándose en el corazón de la marca y de sus fieles moteros. La serie está encabezada por un reparto de estrellas en el que se incluyen Michiel Huisman (Juego de Tronos) como Walter Davidson, Robert Aramayo (Juego de Tronos) como William (Bill) Harley y Bug Hall (Una pandilla de pillos) en la piel de Arthur Davidson. Además, después de cada una de las entregas, Discovery Channel ofrecerá más contenidos en los que las míticas Harley-Davidson son protagonistas, como el documental I’m Evel Knievel, que se ofrece el viernes 30 a partir de las 23,55 horas, centrado en la vida del espectacular piloto de acrobacias extremas Robert Craig Knievel.