1996 Literary Review (No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

ピーター・バラカン 2013 年 6 月 1 日放送 Sun Ra 特

ウィークエンド サンシャイン PLAYLIST ARCHIVE DJ:ピーター・バラカン 2013 年 6 月 1 日放送 Sun Ra 特集 ゲスト:湯浅 学 01. We Travel The Space Ways / Sun Ra & His Astro Infinity Arkestra // Greatest Hits: Easy Listening For Intergalatic Travel 02. Saturn / Sun Ra & His Solar Arkestra // Visits Planet Earth Interstellar Low Ways 03. Dig This Boogie / Wynonie Harris with Jumpin' Jimmy Jackson Band // The Eternal Myth Revealed, Vol.1 04. Message to Earth Man / Yochanan, Sun Ra And The Arkestra // The Singles 05. MU / Sun Ra & His Astro Infinity Arkestra / Atlantis 06. The Design-Cosmos II / Sun Ra & His Astro Infinity Arkestra // My Brother The Wind Volume II 07. The Perfect Man / Sun Ra And His Astro Galactic Infinity Arkestra // The Singles 08. Gods of The Thunder Realm / Sun Ra And His Arkestra // Live At Montreux 09. Rocket#9 / Sun Ra // Space Is The Place 10. Dancing In The Sun / Sun Ra & His Solar Arkestra // The Heliocentric Worlds Of Sun Ra Vol.1 11. Take The A Train / Sun Ra Arkestra // Sunrise In Different Dimensions 12. The Old Man Of The Mountain / Phil Alvin // Phil Alvin Un "Sung Stories" 13. Love In Outer Space / Sun Ra // Purple Night 14. Lanquidity / Sun Ra // Lanquidity 2013 年 6 月 8 日放送 01. You're My Kind Of Climate (Party Mix) / Rip Rig & Panic // Methods Of Dance Volume 2 02. Bold As Love / Jimi Hendrix // The Jimi Hendrix Experience: Box Set 03. Who'll Stop The Rain / John Fogerty with Bob Seger // Wrote A Song For Everyone 04. Fortunate Son / John Fogerty with Foo Fighters // Wrote A Song For Everyone 05. -

Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21St Century Chicago

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21St Century Chicago Adam Zanolini The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1617 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SACRED FREEDOM: SUSTAINING AFROCENTRIC SPIRITUAL JAZZ IN 21ST CENTURY CHICAGO by ADAM ZANOLINI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 ADAM ZANOLINI All Rights Reserved ii Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21st Century Chicago by Adam Zanolini This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________ __________________________________________ DATE David Grubbs Chair of Examining Committee _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Jeffrey Taylor _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Fred Moten _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Michele Wallace iii ABSTRACT Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21st Century Chicago by Adam Zanolini Advisor: Jeffrey Taylor This dissertation explores the historical and ideological headwaters of a certain form of Great Black Music that I call Afrocentric spiritual jazz in Chicago. However, that label is quickly expended as the work begins by examining the resistance of these Black musicians to any label. -

Transcendence” in German History and Politics

THE ACOLYTES OF BEING: A DEFINITION OF “TRANSCENDENCE” IN GERMAN HISTORY AND POLITICS by Emily Stewart Long Honors Thesis Appalachian State University Submitted to the Department of History, the Department of Political Science, and the Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science May, 2015 _____________________________________________________________________ Michael C. Behrent, PhD., History, Thesis Director _____________________________________________________________________ Nancy S. Love, Ph.D., Political Science, Thesis Director ____________________________________________________________________ Benno, Weiner, Ph.D., Department of History, Honors Director ___________________________________________________________________ Elicka Peterson-Sparks, PhD., Department of Political Science, Honors Director _____________________________________________________________________ Leslie Sargent Jones, Ph.D., Director, The Honors College 1 ABSTRACT Acting as my Senior Honors Thesis in the departments of History, Political Science, and University Honors, this project, “The Acolyte of Being,” aims to present an aesthetic history of twentieth century German philosopher Martin Heidegger’s concept of “Da-sein:” the “thereness” of Being (or existence) itself. Taking into account 2,500 years of Western metaphysics, my thesis begins by redefining one key philosophical term: transcendence, and in so doing revive four others as well: truth, beauty, freedom and the term metaphysics itself. As such, this work begins with a “Definition of Transcendence,” informing the following five chapters. These chapters, in keeping with the historicity of Da-sein as an aesthetic one, each name great works of art, opening of the oblivions of Being to man. Each of my chapters follow the guiding definition of “Transcendence” and correspond as well to one of five Wagnerian operas: Das Rheingold, Die Walkyrie, Siegfried, Götterdämmerung and, finally, Parsifal. -

Sounds of Alter-Destiny and Ikonoklast Panzerist Fabulations

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2019 Sounds of Alter-destiny and Ikonoklast Panzerist Fabulations Mette Christiansen The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3401 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SOUNDS OF ALTER-DESTINY AND IKONOKLAST PANZERIST FABULATIONS by METTE CHRISTIANSEN A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 METTE CHRISTIANSEN All Rights Reserved ii SOUNDS OF ALTER-DESTINY AND IKONOKLAST PANZERIST FABULATIONS by Mette Christiansen This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date Susan Buck-Morss Thesis Advisor Date Alyson Cole Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Sounds of Alter-destiny and Ikonoklast Panzerist Fabulations by Mette Christiansen Advisor: Susan Buck-Morss This study is a multifaceted attempt to complicate ideas about study, to think about the critical potential and social implications of certain kinds of stories, and how we might effectively disrupt and reinvent notions and techniques of critique and resistance in the names of hope and social transformation. -

Ghetto Comedies

GHETTO COMEDIE |ii .;i ISRAE ANGWILL iiiiiiiii BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcnrg M. Sage 189X ^,Xi3 iSJl io.f.S..l.i^.a.-^^. 7673-2 Cornell University Library PR 5922.G4 1907 Ghetto comedies, 3 1924 013 577 592 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924013577592 GHETTO COMEDIES ip^y^ Ghetto Comedies BY ISRAEL ZANGWILL AUTHOR OF 'THE GREY WIG,' 'DREAMERS OF THE GHETTO,' 'THE MASTER,' ETC. NeSn got* THE MACMILLAN COMPANY LONDON : WILLIAM HEINEMANN 1907 All rights reserved Copyright, 1907, By the MACMILLAN COMPANY. Set up and electrotyped. Published April, 1907. J. B. Gushing & Oo. — Berwick & Smith Co. Horwood, Mass., U.S.A. TO MY OLD FRIEND M. D. EDER NOTE Simultaneously with the publication of these 'Ghetto Comedies' a fresh edition of my 'Ghetto Tragedies ' is issued, with the original title restored. In the old definition a comedy could be distin- guished from a tragedy by its happy ending. Dante's Hell and Purgatory could thus appertain to a ' comedy.' This is a crude conception of the distinction between Tragedy and Comedy, which I have ventured to disregard, particularly in the last of these otherwise unassuming stories. I. Z. Shottermill, February, 1907. CONTENTS PAGE The Model of Sorrows i Anglicization 57 The Jewish Trinity 103 The Sabbath Question in Sudminster . -137 The Red Mark 197 The Bearer of Burdens 219 The Litftmensch 255 The Tug of Love 281 The Yiddish ' Hamlet ' 293 The Converts 333 Holy Wedlock 3SS Elijah's Goblet 381 The Hirelings 399 Samooborona 427 THE MODEL OF SORROWS THE MODEL OF SORROWS CHAPTER I HOW I FOUND THE MODEL I CANNOT pretend that my ambition to paint the Man of Sorrows had any religious inspiration, though I fear my dear old dad at the Parsonage at first took it as a sign of awakening grace. -

Rodger Coleman Sun Ra Sundays

SUN RA SUNDAYS by Rodger Coleman This is a compilation of blog entries about SUN RA authored by RODGER G. COLEMAN from 2008 to 2015 and posted at nuvoid.blogspot.com. Coleman's blog contains hundreds of posts on a myriad of music subjects; we've culled only the Ra content. We have added no commentary, preferring to let this writing speak for itself. The vast Sun Ra knowledge base covered in Coleman's posts remains vital and historically valid. Identifiable historic inaccuracies (generally based on best-available sources at the time) are neither corrected nor footnoted. These are the posts and responses as they were published online at the time—the verbatim historic record. All copyrights belong to Coleman and the authors of the comments and quoted sources. This chronicle was collected, formatted & edited by Irwin Chusid, with assistance from Kristen Pierce, in November 2018. It is sequenced chronologically. Some unintentional misspelling has been corrected; idiosyncratic spelling, abbreviations, and casual disregard of capitalization niceties (mostly in the comments) were left as written. Most dead links are omitted. Reader comments are highlighted in red (although salutations- only comments have been omitted). Graphic images and photos from the blog are not included. (For graphics, see SAM BYRD's complementary collection of Sun Ra Sundays posts; Byrd also arranged all entries in discographical order.) This content has been collected for preservation, research, and circulation. In some cases, recent findings have amplified, clarified, or superseded particular details or assertions. It would be interesting to crowd-source updates with new information that's come to light since these posts were published. -

Sun Ra Sundays Selections from the Nuvoid Blog

Sun Ra Sundays Selections from the NuVoid Blog by Rodger Coleman 1 Selections from Rodger Coleman's blog NuVoid (http://nuvoid.blogspot.com/), from 2008 to 2015, with selected comments. Minor edits and formatting by Sam Byrd, 2016. Entries have been rearranged chronologically, to match the order given in Chris Trent's discography included in the 2nd edition of Omniverse Sun Ra (since it is more up-to-date than RLC/Trent). © Rodger Coleman 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Spaceship Lullaby.................................................. 7 Music from Tomorrow's World.......................... 8 Bad and Beautiful.................................................. 10 Art Forms of Dimensions Tomorrow............... 11 Out There a Minute.............................................. 13 Secrets of the Sun.................................................. 16 What's New............................................................ 18 The Invisible Shield...............................................19 The Earthly Recordings of Sun Ra, 2nd ed...... 21 When Sun Comes Out......................................... 23 Space Probe [1]...................................................... 24 Continuation [1]..................................................... 26 Continuation [2]..................................................... 28 Space Probe [2]...................................................... 30 A Blue One/Orbitration in Blue........................ 33 Janus........................................................................ 35 Cosmic Tones for Mental -

Dragonfly Monsoon’ and Imagined Oceans: in Search of Poem-Maps of the Swahili Seas

‘Dragonfly Monsoon’ and Imagined Oceans: In Search of Poem-Maps of the Swahili Seas Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor M.A. University of Reading, UK B.A. Kenyatta University, Kenya A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 The School of Communications and Arts Abstract To what extent can a ‘text’ borne in memory give texture, perspectives, meaning, dimensionality and sense to a place? Where is the ‘locus of meaning’ in such a case? Can this locus be traced (mapped, narrated, found)? These questions about Swahili navigational poetry (poem-maps) specific to the Western Indian Ocean first motivated this study. Can such repositories of sea experiences be read for biographical threads of the water body to which they refer? As the search for answers to these questions progressed in the course of the study, it emerged that studies of the Western Indian Ocean’s intimate and imagined geographies through the lives and memories – individual and collective, private and institutional - of those who have had the closest and most extensive relationship with it were not, at present, easily available. The quest turned to narratives in and of the interstices, the ‘small stories’ (micro-narratives), those seemingly ordinary tales of encounter and experience that get obliterated in the retelling of overarching historical (‘China in Africa’) and geographical (‘The Indian Ocean’) phenomena. This thesis, Dragonfly Monsoon (novel excerpt) and Imagined Oceans: in search of poem-maps of the Swahili Seas, becomes an effort to story the ocean. The project does this by drawing from the memories and selected sea poetry of Zanzibar-based Haji Gora Haji, a living mariner, and the maritime lives of fictional mariners who, with Haji Gora Haji, inhabit these shores and waters. -

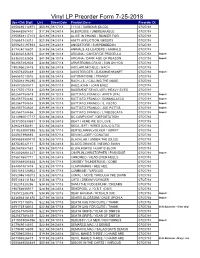

LP Pre-Order Report 7-25-18.Xls

Vinyl LP Preorder Form 7-25-2018 Upc+Chk Digit List Street Date Product Desc Preorder Dt 4050486114971 $50.98 08/17/18 1+1=X / VARIOUS (DLCD) 07/27/18 054645267410 $17.98 08/24/18 ALBOROSIE / UNBREAKABLE 07/27/18 4050538417104 $24.98 08/24/18 ALICE IN CHAINS / RAINIER FOG 07/27/18 016861743314 $21.98 08/24/18 AMITY AFFLICTION / MISERY 07/27/18 4059251197553 $23.98 08/24/18 ANCESTORS / SUSPENDED IN 07/27/18 817424018807 $24.98 08/24/18 ANIMALS AS LEADERS / ANIMALS 07/27/18 633632032615 $41.99 08/10/18 ARCANA / CANTAR DE PROCELLA 07/27/18 Import 633632032608 $41.99 08/10/18 ARCANA / DARK AGE OF REASON 07/27/18 Import 602567492603 $34.98 09/07/18 ARMSTRONG,CRAIG / SUN ON YOU 07/27/18 190295623418 $32.98 08/24/18 AUCLAIR,MICHELE / BACH 07/27/18 616576255449 $39.99 08/10/18 AUSSTEEIGER / ZUSAMMENKUNFT 07/27/18 Import 666561013516 $25.98 08/24/18 AUTOMATISME / TRANSIT 07/27/18 3760014194290 $18.99 08/24/18 BACH,J.S. / CALLING THE MUSE 07/27/18 888072060517 $29.98 09/07/18 BAEZ,JOAN / JOAN BAEZ 07/27/18 621757017518 $25.98 08/24/18 BASEMENT REVOLVER / HEAVY EYES 07/27/18 602567754619 $39.99 08/10/18 BATTIATO,FRANCO / APRITI (ITA) 07/27/18 Import 602567754480 $39.99 08/10/18 BATTIATO,FRANCO / GOMMALACCA 07/27/18 Import 602567754534 $39.99 08/10/18 BATTIATO,FRANCO / IL VUOTO 07/27/18 Import 602567754626 $39.99 08/10/18 BATTIATO,FRANCO / JOE PATTI'S 07/27/18 Import 602567754466 $39.99 08/10/18 BATTIATO,FRANCO / L'IMBOSCATA 07/27/18 Import 5414940017717 $23.98 08/24/18 BC CAMPLIGHT / DEPORTATION 07/27/18 5037300833651 $19.98 08/24/18 BEAT / HERE -

Greek and Roman Mythology

DOCUMENT RESUME ID 064 733 CS 200 026 AUTHOR Hargraves, Richard;Kenzel, Elaine TITLE Greek and RomanMythology: English, Mythology. INSTITUT/ON Dade County Public Schools,Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 53p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Classical Literature; *CourseContent; Course Objectives; *CurriculumGuides; *English Curriculum; Greek Literature; IntegratedActivities; Latin Literature; *Mythology; ResourceGuides IDENTIFIERS *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT The aim of theQuinmester course ',Greekand Roman Mythologyn is to help studentsunderstand mythologicalreferences in literature, art, music,science and technology. Thesubject matter includes: creation myths;myths of gods and heroes;mythological allusions in astrology,astronomy, literature,science, business, puzzles, and everyday speech;and myths in visual art,music, classic Greek tragedy, philosophy,and in the comparativeand analytical study of the Great Ages ofMan. A 13-pagelisting of resource es materials for studentsand teachers is included. gn4 AUTHORIZED COURSE OF INSTRUCTION FOR THE GREEK AND ROMAN MYTHOLOGY 5132.21 5112 .26 5113.42 5114.43 0 5115.43 5116.143 53.88.0 English9 Mythology DIVISION OF INSTRUCTION1911 U.S. DEPARTMENT OP MAIM EDUCATION Si MIAMI OPPICI OP EDUCATION TINS DOCUMENT NMI SUN REPRO. WOO INACTLY AS NICENE PROM THE PERSON ON OROANIEATION OMO. INATING IT. POINTS OP VIEW ON OPIN. IONS STATED 00 NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OPPICIAL OFFICE OP IOU. CATION POSITION ON POLICY. GREEK AND ROMAN MYTHOLOGY 5111. 21 5112. 26 5113. 42 5114. 43 5115. 43 5116. 43 5188. 03 English, Mythology Written by Richard Hargraves and Elaine Kenzel for the DIVISION OF INSTRUCTION Dade County Public Schools Miami, Florida 1971 "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THISCOPY. RIGHTED MATERIAL HAS SEENGRANTED SY Dade County Public Schools TO ERIC AND ORGANIZATIONSOPERATING UNDER AGREEMENTS WITHTHE U.S OFFICE OF EDUCATION FURTHERREPRODUCTION OUTSIDE THE ERIC SYSTEMREQUIRES PER MISSION OF THE COPYRIGHTOWNER DADE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD Mr. -

AVAILABLE from a Resource Bulletin for Teachers of En Lish: Grade Baltimore Coun Y Foard of Education, Towson, Maryland Communic

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 061 192 TE 002 783 TITLE A Resource Bulletin for Teachers of En_lish: Grade Eight. INSTITUTI_ Baltimore County Public Schools, Towson, Md. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 404p. AVAILABLE FROM Baltimore Coun y Foard of Education, Towson, Maryland 21204 ($8.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$16.45 DESCRIPTORS Academic Achievement; Attitudes; Bulletins; Communication skills; *Course Content; Cultural Enrichment; *Educational Objectives; Educational Programs; *English Curriculum; Environmental Influences; Evaluation; *Grade 8; Junior High Schools; Motivation Techniques; Reading Skills; *Resource Materials; Second Language Learning: Standards; Student Ability; Task Performance; Teachers; Teaching Guides ABSTRACT This document is a guide for the junior high school and is aimed at the average and above-average student in the regular English program. Objectives of the English program, among others, are: (1) to help pupils appreciate that language is the basis of all culture, (2) to provide opportunities in a natural setting for the practice of communication skills which will promote desirable human relationships and effective group participation, CO to train in those language competencies which promote success in school, ((4) to develop pupil motivation for greater proficiency in the use of language, (5) to teach pupils to listen attentively and analytically and to evaluate what they hear, (6) to give pupils a sense of security in the use of their native tongue,(7) to develop competence in those reading skills and appreciations necessary for the performance of school tasks,(8) to help pupils develop critical attitudes and standards in evaluating and choosing among books and periodicals, (9) to provide pupils with opportunities for creative expression on the level of their capacities and interests, and (10) to promote awareness and u8e of the cultural facilities in the metropolitan community.