The Angry Brigade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stuart Christie Obituary | Politics | the Guardian

8/29/2020 Stuart Christie obituary | Politics | The Guardian Stuart Christie obituary Anarchist who was jailed in Spain for an attempt to assassinate Franco and later acquitted of being a member of the Angry Brigade Duncan Campbell Mon 17 Aug 2020 10.40 BST In 1964 a dashing, long-haired 18-year-old British anarchist, Stuart Christie, faced the possibility of the death penalty in Madrid for his role in a plot to assassinate General Franco, the Spanish dictator. A man of great charm, warmth and wit, Christie, who has died of cancer aged 74, got away with a 20-year prison sentence and was eventually released after less than four years, only to find himself in prison several years later in Britain after being accused of being a member of the Angry Brigade, a group responsible for a series of explosions in London in the early 1970s. On that occasion he was acquitted, and afterwards he went on to become a leading writer and publisher of anarchist literature, as well as the author of a highly entertaining memoir, Granny Made Me an Anarchist. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/aug/17/stuart-christie-obituary 1/5 8/29/2020 Stuart Christie obituary | Politics | The Guardian Christie’s Franco-related mission was to deliver explosives to Madrid for an attempt to blow up the Spanish leader while he attended a football match at the city’s Bernabéu stadium. Telling his family that he was going grape-picking in France, he went first to Paris, where it turned out that the only French he knew, to the amusement of his anarchist hosts, was “Zut, alors!” There he was given explosives and furnished with instructions on how to make himself known to his contact by wearing a bandage on his hand. -

Cornell International Affairs Review Editor-In-Chief Stephany Kim ’19

1 Cornell International Affairs Review Editor-in-Chief Stephany Kim ’19 Managing Editor Ronni Mok ’20 Graduate Editors Amanda Cheney Caitlin Mastroe Martijn Mos Katharina Obermeier Whitney Taylor Youyi Zhang Undergraduate Editors Victoria Alandy ’20 Carmen Chan ’19 Christopher Cho ’17 Nidhi Dontula ’20 Gage DuBose ’18 Michelle Fung ’19 Matthew Gallanty ’18 Yuichiro Kakutani ’19 Beth Kelley ’19 Veronika Koziel ’19 Ethan Mandell ’18 Tola Mcyzkowska ’17 Ryan Norton ’17 Juliette Ovadia ’20 Srinand Paruthiyil ’19 Chasen Richards ’18 Xavier Salvador ’19 Julia Wang ’19 Yuijing Wang ’20 Design Editors Yuichiro Kakutani ’19 Yujing Wang ’20 Executive Board President Sohrab Nafisi ’18 Treasurer Ronni Mok ’20 VP of Programming Xavier Salvador ’19 Volume X Spring 2017 2 The Cornell International Affairs Review Board of Advisors Dr. Heike Michelsen, Primary Advisor Associate Director of Academic Programming, Einaudi Center for International Studies Professor Robert Andolina Johnson School of Management Professor Ross Brann Department of Near Eastern Studies Professor Matthew Evangelista Department of Government Professor Peter Katzenstein Department of Government Professor Isaac Kramnick Department of Government Professor David Lee Department of Applied Economics and Management Professor Elizabeth Sanders Department of Government Professor Nina Tannenwald Brown University Professor Nicolas van de Walle Department of Government Cornell International Affairs Review, an independent student organization located at Cornell University, produced and is responsible -

CHAPTER VI Individualism and Futurism: Compagni in Milan

I Belong Only to Myself: The Life and Writings of Leda Rafanelli Excerpt from: CHAPTER VI Individualism and Futurism: Compagni in Milan ...Tracking back a few years, Leda and her beau Giuseppe Monanni had been invited to Milan in 1908 in order to take over the editorship of the newspaper The Human Protest (La Protesta Umana) by its directors, Ettore Molinari and Nella Giacomelli. The anarchist newspaper with the largest circulation at that time, The Human Protest was published from 1906–1909 and emphasized individual action and rebellion against institutions, going so far as to print articles encouraging readers to occupy the Duomo, Milan’s central cathedral.3 Hence it was no surprise that The Human Protest was subject to repeated seizures and the condemnations of its editorial managers, the latest of whom—Massimo Rocca (aka Libero Tancredi), Giovanni Gavilli, and Paolo Schicchi—were having a hard time getting along. Due to a lack of funding, editorial activity for The Human Protest was indefinitely suspended almost as soon as Leda arrived in Milan. She nevertheless became close friends with Nella Giacomelli (1873– 1949). Giacomelli had started out as a socialist activist while working as a teacher in the 1890s, but stepped back from political involvement after a failed suicide attempt in 1898, presumably over an unhappy love affair.4 She then moved to Milan where she met her partner, Ettore Molinari, and turned towards the anarchist movement. Her skepticism, or perhaps burnout, over the ability of humans to foster social change was extended to the anarchist movement, which she later claimed “creates rebels but doesn’t make anarchists.”5 Yet she continued on with her literary initiatives and support of libertarian causes all the same. -

Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................2 2. The Principles of Anarchism, Lucy Parsons....................................................................3 3. Anarchism and the Black Revolution, Lorenzo Komboa’Ervin......................................10 4. Beyond Nationalism, But not Without it, Ashanti Alston...............................................72 5. Anarchy Can’t Fight Alone, Kuwasi Balagoon...............................................................76 6. Anarchism’s Future in Africa, Sam Mbah......................................................................80 7. Domingo Passos: The Brazilian Bakunin.......................................................................86 8. Where Do We Go From Here, Michael Kimble..............................................................89 9. Senzala or Quilombo: Reflections on APOC and the fate of Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio...........................................................................................................................91 10. Interview: Afro-Colombian Anarchist David López Rodríguez, Lisa Manzanilla & Bran- don King........................................................................................................................96 11. 1996: Ballot or the Bullet: The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Electoral Process in the U.S. and its relation to Black political power today, Greg Jackson......................100 12. The Incomprehensible -

The New York City Draft Riots of 1863

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1974 The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863 Adrian Cook Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cook, Adrian, "The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863" (1974). United States History. 56. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/56 THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS This page intentionally left blank THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS TheNew York City Draft Riots of 1863 ADRIAN COOK THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY ISBN: 978-0-8131-5182-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-80463 Copyright© 1974 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 To My Mother This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix -

Conceptions of Terror(Ism) and the “Other” During The

CONCEPTIONS OF TERROR(ISM) AND THE “OTHER” DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF THE RED ARMY FACTION by ALICE KATHERINE GATES B.A. University of Montana, 2007 B.S. University of Montana, 2007 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures 2012 This thesis entitled: Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction written by Alice Katherine Gates has been approved for the Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures _____________________________________ Dr. Helmut Müller-Sievers _____________________________________ Dr. Patrick Greaney _____________________________________ Dr. Beverly Weber Date__________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Gates, Alice Katherine (M.A., Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures) Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction Thesis directed by Professor Helmut Müller-Sievers Although terrorism has existed for centuries, it continues to be extremely difficult to establish a comprehensive, cohesive definition – it is a monumental task that scholars, governments, and international organizations have yet to achieve. Integral to this concept is the variable and highly subjective distinction made by various parties between “good” and “evil,” “right” and “wrong,” “us” and “them.” This thesis examines these concepts as they relate to the actions and manifestos of the Red Army Faction (die Rote Armee Fraktion) in 1970s Germany, and seeks to understand how its members became regarded as terrorists. -

Socialism – an Introduction

Socialism – An Introduction. Socialism can be defined as a social order that raises the living standards of the majority by a fair and equal redistribution of wealth and work, that looks after those most in need, doesn't consign them to the scrap heap of poverty and despair. Based on compassion for all humanity, and the belief that a small minority should not hold the majority of wealth, socialism is not about one rule for all, a colourless world, but about allowing each individual the access to develop their own unique skills and character, thus benefiting the community as a whole. Socialism does not discriminate on ground of creed, colour or sex, but embraces all peoples lives, a fervently believes in the good within us all and utilising these qualities for the benefit of everyone, not the selfish few. Often attacked as idealistic, socialism is an easily attainable state, a true and powerful way of abolishing all inequality and prejudice. Some socialist demands for the late 20th Century Britain. 1. Socialist measures in the interests of working people! Labour must break with big business and Tory economic policies. 2. Full employment! 3. No redundancies. 4. The right to a job or decent benefits. For a 32 hour week without loss of pay. 5. No compulsory overtime. 6. For voluntary retirement at 55 with a decent full pension for all. 7. A national minimum wage of at least two-thirds of the average wage. £4.61 an hour as a step toward this goal, with no exemptions. 8. The repeal of all Tory anti-union laws. -

Burn It Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985

Burn it Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985 by Eryk Martin M.A., University of Victoria, 2008 B.A. (Hons.), University of Victoria, 2006 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Eryk Martin 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2016 Approval Name: Eryk Martin Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (History) Title: Burn it Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985 Examining Committee: Chair: Dimitris Krallis Associate Professor Mark Leier Senior Supervisor Professor Karen Ferguson Supervisor Professor Roxanne Panchasi Supervisor Associate Professor Lara Campbell Internal Examiner Professor Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Joan Sangster External Examiner Professor Gender and Women’s Studies Trent University Date Defended/Approved: January 15, 2016 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract This dissertation investigates the experiences of five Canadian anarchists commonly knoWn as the Vancouver Five, Who came together in the early 1980s to destroy a BC Hydro power station in Qualicum Beach, bomb a Toronto factory that Was building parts for American cruise missiles, and assist in the firebombing of pornography stores in Vancouver. It uses these events in order to analyze the development and transformation of anarchist activism between 1967 and 1985. Focusing closely on anarchist ideas, tactics, and political projects, it explores the resurgence of anarchism as a vibrant form of leftWing activism in the late tWentieth century. In addressing the ideological basis and contested cultural meanings of armed struggle, it uncovers Why and how the Vancouver Five transformed themselves into an underground, clandestine force. -

The Barnes Review SOBIBÓR a JOURNAL of NATIONALIST THOUGHT & HISTORY HOLOCAUSTPROPAGANDAANDREALITY VOLUME XVI NUMBER 4 JULY/AUGUST 2010 BARNESREVIEW.ORG

WHAT IS THE TRUTH ABOUT THE SOBIBOR CONCENTRATION CAMP? FIND OUT! BRINGING HISTORY INTO ACCORD WITH THE FACTS IN THE TRADITION OF DR. HARRY ELMER BARNES The Barnes Review SOBIBÓR A JOURNAL OF NATIONALIST THOUGHT & HISTORY HOLOCAUSTPROPAGANDAANDREALITY VOLUME XVI NUMBER 4 JULY/AUGUST 2010 BARNESREVIEW.ORG A scholarly examination of the infamous Nazi “death camp” NEW FROM TBR: By Juergen Graf, Carlo Mattogno & Thomas Kues n May 2009, the 89-year-old Cleveland autoworker John Demjanjuk was deported from the United States to Germany, where he was arrested and charged with aiding and abetting murder in at least 27,900 cases. These mass murders were allegedly perpetrated at the Sobibór “death” Icamp in eastern Poland. According to mainstream historiography, 170,000 to 250,000 Jews were exterminated here in gas chambers between May 1942 and October 1943. The corpses were buried in mass graves and later incinerated on an open-air pyre. A DAGGER IN THE But do these claims really stand up to scrutiny? SOBIBOR In this book, the official version of what transpired at LEGEND Sobibór is put under the scanner. It is shown that the historiog- raphy of the camp is not based on solid evidence, but on the selec- tive use of eyewitness testimonies, which in turn are riddled with con- tradictions and outright absurdities. Could this book exonerate falsely accused John Demjanjuk? For more than half a century mainstream Holocaust historians made no real attempts to muster material Also in this issue: evidence for their claims about Sobibór. Finally, in the 21st century, professional historians carried out an archeological survey at the former camp site. -

Dossier: Les Prisonniers Politiques Ouest-Allemands Accusent

1·- LesTeßlps Modernes Dlr~cteur JEAN-PAUL SARTRE 2ge annee Mars 1974 N° 332 ROSSANA ROSSANDA. - Les intellectuels revolutionnaires et I'Union •sovietique EDOUARD KOUZNETSOV. - Journal d'un condamne a mort• DOSSIER LES PRISONNIERS POLITIQUES OUEST·ALLEMANDS ACCUSENT VIKTOR KLEINKRIEG. - Les combattants anti-imperialistes face a la torture SJEF TEUNS. - La torture par privation sensorielle XXX. - Les methodes scientifiques de torture CHRISTIAN SIGRIST. - De Heidelberg au Cap Vert KLAUS' CROISSANT. - La Justice et la torture par I'isolement - Des detenus politiques• temoignent - CHRONIQUES Le sexisme ordinaire RENEE SAUREL. - « Nicomede » ou « Nuc;lea » : Lettre ouverte a Roger Planchon. -« Odin-Teatret ) lRome CHRISTIAN ZIMMER. - Tetes de Turcs et t8tes de Bretons •.~ REDACTION, ADMINISTRATION.•26. RUE DE CONDE, PARIS -·6· ~ " '0. DOSSIER LES PRISONNIERS POLITIQ!lES OUEST-ALLEMANDS ACCUSENT Viktor Kleinkrieg 11I11 LES COMBATTANTS ANTI-IMP~RIALISTES FACE A LA TORTURE Il .faut reconna'itre que la torture est prati• quee afin de permettre aux rapports de propriete de se perpetuer. Bien sur, en disant cela nous perdons beaucoup d'amis. Ceux-ci s'opposent a la torture, mais aussi ils pensent que /'on peut main• I tenir les rapports de propriete sans faire usage de la torture. Ce qui n'est pas vrai. Bertolt BRECHT. 111 I1 « Travailler: du latin populaire, torturer avec le tripalium (vers 1080); 11 I travail : I'etat de celui qui souffre, qui est tourmente. » (Tire du dictionnaire Le petit Rober!.) Les textes qui suivent, s'ils constituent une denonciation des tortures exercees legalement par les autorites judiciaires de la Republique federale d'AIIemagne, se veulent surtout un temoi• gnage sur la resistance de ceux qui sont victimes de ces pra• tiques : les prisonniers politiques. -

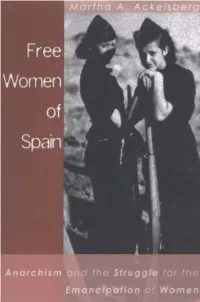

Ackelsberg L

• • I I Free Women of Spain Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women I Martha A. Ackelsberg l I f I I .. AK PRESS Oakland I West Virginia I Edinburgh • Ackelsberg. Martha A. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women Lihrary of Congress Control Numher 2003113040 ISBN 1-902593-96-0 Published hy AK Press. Reprinted hy Pcrmi"inn of the Indiana University Press Copyright 1991 and 2005 by Martha A. Ackelsherg All rights reserved Printed in Canada AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612-1163 USA (510) 208-1700 www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh. EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555-5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] The addresses above would be delighted to provide you with the latest complete AK catalog, featur ing several thousand books, pamphlets, zines, audio products, videos. and stylish apparel published and distributed bv AK Press. A1tern�tiv�l�! Uil;:1t r\llr "-""'l:-,:,i!'?� f2":' �!:::: :::::;:;.p!.::.;: ..::.:.:..-..!vo' :uh.. ,.",i. IIt;W� and updates, events and secure ordering. Cover design and layout by Nicole Pajor A las compafieras de M ujeres Libres, en solidaridad La lucha continua Puiio ell alto mujeres de Iberia Fists upraised, women of Iheria hacia horiz,ontes prePiados de luz toward horizons pregnant with light por rutas ardientes, on paths afire los pies en fa tierra feet on the ground La frente en La azul. face to the blue sky Atirmondo promesas de vida Affimling the promise of life desafiamos La tradicion we defy tradition modelemos la arcilla caliente we moLd the warm clay de un mundo que nace del doLor. -

5-28-1972 Bonn Gets Warning of More Bombings

11/4/11 From the archive: May 28 1972: Bonn gets warning of more bombings | Wor… Printing sponsored by: From the archive: May 28 1972 Bonn gets warning of more bombings May 28 1972: Neal Ascherson reports on the mood of panic across West Germany as Baader-Meinhof conduct a wave of attacks Neal Ascherson The Observ er, Saturday 27 May 1 97 2 l ar ger | smal l er The wave of bombings in West Germany, culminating on Wednesday in the death of three American soldiers when a parked car exploded at the United States Army headquarters at Heidelberg, may not yet have reached its peak. An urban guerrilla 'commando' has warned that there will be attacks in major cities next Friday, and proclaimed: 'The armed struggle has begun...only violence can help, when violence rules.' The attacks are deeply alarming the Government. Herr Genscher, Minister of the Interior, said that counter-intelligence squads would be enlarged. The head of the Federal Criminal Office booked 10 minutes of television on Thursday night to appeal to the public to act as detectives against the bombers. On Friday, Chancellor Brandt called an emergency conference of provincial Ministers of the Interior to study the problem. It seems likely that the urban guerrilla groups loosely united in the 'Red Army Faction' have become stronger in spite of a three-year manhunt. The nucleus was the group led by Ulrike Meinhof and Andreas Baader, both still at large although several members of the band have been killed in gun battles, captured or have given themselves up.