The Distortion Paradox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Machine Head: Inside the Machine Online

vmBnJ (Read free) Machine Head: Inside the Machine Online [vmBnJ.ebook] Machine Head: Inside the Machine Pdf Free Joel McIver *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #2428498 in Books 2013-04-01Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.26 x .91 x 6.29l, .98 #File Name: 178038551X272 pages | File size: 44.Mb Joel McIver : Machine Head: Inside the Machine before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Machine Head: Inside the Machine: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Good for the casual fans, maybe a bit of a letdown for the hardcore onesBy Stefan TopuzovMachine Head is probably my favorite band ever. And I have been following them very closely for about a decade and a half now, reading all the available interviews they had given, digging old news articles from their earlier periods, building up a ridiculously extensive collection of old magazine scans, live bootlegs, TV appearances and what not...And maybe because of that, this book was a bit of a let down for me because it didn't provide anything that I didn't already know. In fact, a few times I actually felt I knew more than what was actually in the book.Then again, I gave the book to my father, who's also a fan of rock and metal. He read it, loved it, and decided to look deeper into the band and now he blasts The Blackening and Burn My Eyes every now and then.So, basically, how much you'll like this book – or if you need to purchase it – depends on how deep into the band you are. -

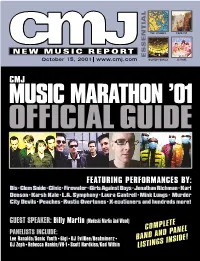

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

9781317587255.Pdf

Global Metal Music and Culture This book defines the key ideas, scholarly debates, and research activities that have contributed to the formation of the international and interdisciplinary field of Metal Studies. Drawing on insights from a wide range of disciplines including popular music, cultural studies, sociology, anthropology, philos- ophy, and ethics, this volume offers new and innovative research on metal musicology, global/local scenes studies, fandom, gender and metal identity, metal media, and commerce. Offering a wide-ranging focus on bands, scenes, periods, and sounds, contributors explore topics such as the riff-based song writing of classic heavy metal bands and their modern equivalents, and the musical-aesthetics of Grindcore, Doom and Drone metal, Death metal, and Progressive metal. They interrogate production technologies, sound engi- neering, album artwork and band promotion, logos and merchandising, t-shirt and jewelry design, and the social class and cultural identities of the fan communities that define the global metal music economy and subcul- tural scene. The volume explores how the new academic discipline of metal studies was formed, while also looking forward to the future of metal music and its relationship to metal scholarship and fandom. With an international range of contributors, this volume will appeal to scholars of popular music, cultural studies, social psychology and sociology, as well as those interested in metal communities around the world. Andy R. Brown is Senior Lecturer in Media Communications at Bath Spa University, UK. Karl Spracklen is Professor of Leisure Studies at Leeds Metropolitan Uni- versity, UK. Keith Kahn-Harris is honorary research fellow and associate lecturer at Birkbeck College, UK. -

Thrash Metal Klassiker & NWOTM

#heavymetalgrundschule Thrash Metal Klassiker & NWOTM Teilnehmer: 126 TOP 23 Klassiker-Alben alle Alben mit mindestens 3 Nennungen 1. EXODUS BONDED BY BLOOD (47) 2. SLAYER REIGN IN BLOOD (45) 3. SODOM AGENT ORANGE (41) 4. KREATOR PLEASURE TO KILL (30) 5. METALLICA RIDE THE LIGHTNING (28) 6. SEPULTURA BENEATH THE REMAINS (24) 7. TESTAMENT THE LEGACY (23) 8. ANTHRAX AMONG THE LIVING (22) MEGADETH RUST IN PEACE 9. SODOM PERSECUTION MANIA (21) 10. METALLICA KILL 'EM ALL (20) 11. DARK ANGEL DARKNESS DESCENDS (19) 12. METALLICA MASTER OF PUPPETS (18) SEPULTURA ARISE 13. SLAYER SEASONS IN THE ABYSS (15) SLAYER SOUTH OF HEAVEN 14. DEATH ANGEL THE ULTRA VIOLENCE (13) EXHORDER SLAUGHTER IN THE VATICAN KREATOR EXTREME AGGRESSION MEGADETH PEACE SELLS...BUT WHO' BUYING 15. DEMOLITION HAMMER EPIDEMIC OF VIOLENCE (11) EXUMER POSSESSED BY FIRE OVERKILL THE YEARS OF DECAY 16. ANNIHILATOR ALICE IN HELL (10) DESTRUCTION INFERNAL OVERKILL KREATOR COMA OF SOULS SLAYER SHOW NO MERCY VIO-LENCE ETERNAL NIGHTMARE 17. ANTHRAX SPREADING THE DISEASE (9) EXODUS FABULOUS DISASTER OVERKILL FEEL THE FIRE S.O.D. SPEAK ENGLISCH OR DIE 18. FLOTSAM & JETSAM DOOMSDAY FOR THE DECEIVER (8) FORBIDDEN FORBIDDEN EVIL HOLY MOSES FINISHED WITH THE DOGS KREATOR ENDLESS PAIN METALLICA ...AND JUSTICE FOR ALL OVERKILL TAKING OVER 19. NUCLEAR ASSAULT GAME OVER (7) ONSLAUGHT THE FORCE SACRED REICH THE AMERICAN WAY SEPULTURA CHAOS A.D. SEPULTURA SCHIZOPHRENIA www.krachmuckertv.de SLAYER HELL AWAITS 20. ARTILLERY BY INHERITANCE (6) NUCLEAR ASSAULT HANDLE WITH CARE SACRED REICH IGNORANCE SADUS SWALLOWED IN BLACK TESTAMENT THE NEW ORDER 21. DEATH ANGEL ACT III (5) DESTRUCTION ETERNAL DEVASTATION DESTRUCTION RELEASE FROM AGONY EVIL DEAD ANNIHILATION OF CIVILIZATION FORBIDDEN TWISTED INTO FORM HOLY TERROR MIND WARS MORBID SAINT SPECTRUM OF DEATH WHIPLASH POWER AND PAIN 22. -

RECORD SHOP Gesamtkatalog

RECORD SHOP Gesamtkatalog gültig bis 31.10.2018 Record Shop Holger Schneider Flurstr. 7, 66989 Höheinöd, Germany Tel.: (0049) 06333-993214 Fax: (0049) 06333-993215 @Mail: [email protected] Homepage: www.recordshop-online.de Gruppe / Titel Artikelbeschreibung B.-Nr.Preis Gruppe / Titel Artikelbeschreibung B.-Nr. Preis 10 CC LIVE CD D/92/ATCO M/M- 94179 6,99 € GREATEST HITS 1972 - 1978 CD M-/M 90675 4,99 € LIVE CD-DO Doppel-CD Collectors Edition im Digi von 2003 M/M50405 6,99 € LIVE AT RIVER PLATE DVD VG/VG- 02931 4,99 € 12 STONES NO BULL VHS LIVE PLAZA DE TOROS 122 MINUTEN00502 2,99 € 12 STONES CD M-/M 97005 6,99 € POWERAGE CD Digitaly Remastered AC/DC Collection EX-/M96500 4,99 € POTTERS FIELD CD M/M 97004 6,99 € POWERAGE CD Digitaly Remastered AC/DC Collection M-/M57652 6,99 € 18 SUMMERS ROCK OR BUST CD Lim. Edition im Digipack !!! EX/M 96501 6,99 € VIRGIN MARY CD EX-/M- 93108 6,99 € ROCK OR BUST CD Lim. Edition im Digipack !!! ORIGINALVERPACKT93937 9,99 € 24-7 SPYZ SATELLITE BLUES CD Maxi EX/M 70348 4,99 € 6 CD EX/M 85408 2,99 € STIFF UPPER LIP CD EX-/M 53656 6,99 € STIFF UPPER LIP CD Maxi EX-/M- 61532 4,99 € 36 CRYZYFISTS STIFF UPPER LIP LIVE DVD 2001 M-/M 02085 9,99 € COLLISIONS AND CASTWAYS CD M/M 89364 2,99 € THE RAZORS EDGE CD D/1990/ACTO M-/M 83231 6,99 € 38 SPECIAL THUNDERSTRUCK CD Maxi + Fire Your Guns + D.T. -

Liste Gebrauchtware Privatkunden Datum

TWS-Source Of Deluge - Delmenhorst -- FON 04221-452011 -- FAX 04221-452012 Liste Gebrauchtware Privatkunden Seite: 1 Artikelnummer Interpret Titel Jahr Preis Beschreibung 310 G 42269 13 ENGINES A BLUR TO ME NOW 1991 7,00 € cut out 310 G 55515 28 DAYS UPSTYLEDOWN 2000 5,00 € limited edition with cd rom 320 G 60594 38 SPECIAL TOUR DE FORCE 1983 12,00 € LP 327 G 44956 38 SPECIAL YOU KEEP RUNNING AWAY 1982 4,00 € 7" vinyl single, written on 310 G 11847 40 GRIT NOTHING TO REMEMBER 2003 3,00 € 310 G 5454 454 BIG BLOCK YOUR JESUS 1995 2,00 € 327 G 44777 46 SHORT / KROMBACHERKELLERKINDER SPLIT 5,00 € 7" clear vinyl single 313 G 48055 4LYN LYN 2001 2,00 € MCD 310 G 13839 4LYN SAME 2001 5,00 € 327 G 44860 707 HELL OR HIGH WATER / MEGA FORCE 1982 3,00 € 7" Single 310 G 7738 88 CRASH FIGHT WICKET PENCES 1993 2,00 € 310 G 25423 A D SAME 1993 3,00 € 327 G 61780 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS I RAN 1982 8,00 € LP Vinyl Maxi Single small 310 G 30902 A PERFECT CIRCLE THIRTENTH STEP 2003 9,00 € 320 G 12156 AARON, LEE CALL OF THE WILD 1985 4,00 € LP 327 G 61726 AARON, LEE POWERLINE 1987 4,00 € one sided 7 inch single, 320 G 23334 AARON, LEE SAME 1987 4,00 € LP 320 G 64407 AARON, LEE SAME 1982 5,00 € LP 310 G 6181 ABADDON I AM LEGION 2000 5,00 € 310 G 8810 ABOMINATION RITES OF THE ETERNAL HATE 2000 5,00 € 310 G 47223 ABSORBED SUNSET BLEEDING 1999 16,00 € 310 G 64482 ABSTUERZENDE BRIEFTAUBEN DER LETZTE MACHT DIE TÜR ZU 7,00 € 310 G 53022 ABSTÜRZENDE BRIEFTAUBEN AUSSER KONTROLLE 1992 7,00 € 60 minute live cd 310 G 55825 ABSTÜRZENDE BRIEFTAUBEN DAS KRIEGEN WIR SCHON HIN -

313 3D in Your Face 44 Magnum 5 X a Cosmic Trail A

NORMALPROGRAMM, IMPORTE, usw. Richtung Within Temptation mit einem guten Schuß Sentenced ALLOY CZAR ANGEL SWORD ACCUSER Awaken the metal king CD 15,50 Rebels beyond the pale CD 15,50 Dependent domination CD 15,50 Moderater NWoBHM Sound zwischen ANGRA BITCHES SIN, SARACEN, DEMON, Secret garden CD 15,50 Diabolic CD 15,50 SATANIC RITES gelegen. The forlorn divide CD 15,50 ALLTHENIKO ANGRA (ANDRE MATOS) Time to be free CD 29,00 ACID Back in 2066 CD 15,50 Japan imp. Acid CD 18,00 Devasterpiece CD 15,50 ANGUISH FORCE Engine beast CD 18,00 Millennium re-burn CD 15,50 2: City of ice CD 12,00 ACRIDITY ALMANAC 3: Invincibile imperium Italicum CD 15,50 For freedom I cry & bonustracks CD 17,00 Tsar - digibook CD & DVD 18,50 Cry, Gaia cry CD 12,00 ACTROID ALMORA Defenders united MCD 8,00 Crystallized act CD 29,00 1945 CD 15,50 Japan imp. RRR (1998-2002) CD 15,50 Kalihora´s song CD 15,50 Sea eternally infested CD 12,00 ABSOLVA - Sid by side CD 15,50 ADRAMELCH Kiyamet senfonisi CD 15,50 Broken history CD 15,50 ANIMETAL USA Shehrazad CD 15,50 Lights from oblivion CD 15,50 W - new album 2012 CD 30,00 313 ALTAR OF OBLIVION Japan imp. Opus CD 15,50 Three thirteen CD 17,00 Salvation CD 12,00 ANNIHILATED ADRENALINE KINGS 3D IN YOUR FACE ALTERED STATE Scorched earth policy CD 15,50 Same CD 15,50 Faster and faster CD 15,50 Winter warlock CD 15,50 ANNIHILATOR ADRENICIDE Eine tolle, packende Mischung aus AMARAN Alice in hell CD 12,00 PREMONITION (Florida) ILIUM, HAN- War begs no mercy CD 15,50 KER und neueren JAG PANZER. -

MACHINE HEAD Unto the Locust (Thrash)

MACHINE HEAD Unto the locust (Thrash) Année de sortie : 2011 Nombre de pistes : 7 Durée : 49' Support : CD Provenance : Reçu du label Dans les années 90, MACHINE HEAD a développé avec PANTERA un courant plus moderne du Thrash Metal, une approche plus basique et directe que celle proposée par le courant californien de la Bay Area : une sorte de Power Metal « in your face » au son de guitare grave, à la production en béton signée Colin RICHARDSON, le producteur du moment, répondant aux attentes d’un jeune public. Dans ce style, les deux premiers opus Burn My Eyes en 1994 et The More Things Change en 1997 sont devenus des classiques, les morceaux Davidian, Old et Ten Ton Hammer figurant toujours dans les set list du groupe. Robb FLYNN, chanteur, guitariste, principal compositeur et fondateur n’a jamais caché ses influences dans le Metal classique allant de BLACK SABBATH à JUDAS PRIEST. MACHINE HEAD, grâce à une forte expérience scénique et un gros travail régulier a acquis beaucoup d’expérience au fil du temps et a fait mûrir progressivement sa musique vers quelque chose de plus complexe et de plus mélodique. Ainsi, The Blackening qui sort en 2007 constitue son "Black album", un disque Thrash metal complètement abouti au succès commercial mérité. Il s’en suit une immense tournée de plus de 300 dates afin de promouvoir cet album, notamment en première partie de METALLICA ou de SLIPKNOT. Difficile donc de sortir l’album suivant en 2011…A lieu de se mettre la pression, c’est avec une totale liberté que MACHINE HEAD a composé Locust. -

Content Orchid

OPETH Content Orchid CELESTIAL SEASON Solar Lovers AVANT-GARDE METAL 1 A Brief And Incomplete History MR. BUNGLE Of An Ongoing Experiment Disco Volante VED BUENS ENDE... Written In Waters 1980s 4 FLEURETY Min Tid Skal Komme CELTIC FROST MISANTHROPE Into The Pandemonium 1666...Theatre Bizarre VOIVOD RRRÖÖÖAAARRR 1996 25 VOIVOD Nothingface BAL-SAGOTH Starfire Burning On The Ice- Veiled Throne Of Ultima Thule early 1990s 8 MYSTICUM SCORN In The Streams Of Inferno Vae Solis OXIPLEGATZ DISHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Worlds And Worlds Not To Be Undimensional Conscious ARCTURUS Aspera Hiems Symfonia THE 3RD AND THE MORTAL Sorrow AMORPHIS Elegy ULVER Vargnatt 1997 33 CYNIC Focus BETHLEHEM Sardonischer Untergang DIABOLOS RISING Im Zeichen Irreligiöser 666 Darbietung UNHOLY SEPTIC FLESH The Second Ring Of Power The Ophidian Wheel TIAMAT SIGH Wildhoney Hail Horror Hail ANUBI 1995 17 Kai Pilnaties Akis Uzmerks Mirtis KOROVA OPETH A Kiss In The Charnel Fields My Arms, Your Hearse ARCTURUS La Masquerade Infernale 1999 55 ENOCHIAN CRESCENT CARNIVAL IN COAL Telocvovim French Cancan STRAPPING YOUNG LAD THE KOVENANT City Animatronic THE DILLINGER ESCAPE PLAN ARCTURUS The Dillinger Escape Plan (EP) Disguised Masters IN THE WOODS... IN THE WOODS... Omnio Strange In Stereo ANGIZIA SAMAEL Das Tagebuch Der Hanna Anikin Eternal SOLEFALD 1998 47 Neonism BEYOND DAWN DøDHEIMSGARD Revelry 666 International OXIPLEGATZ PECCATUM Sidereal Journey Strangling From Within STILLE VOLK OPETH Ex-uvies Still Life KOROVA Dead Like An Angel 2000 65 THE KOVENANT AGHORA Nexus Polaris Aghora BAL-SAGOTH FLEURETY Battle Magic Department Of Apocalyptic Affairs ULVER Themes From William Blake's The RAM-ZET Marriage Of Heaven And Hell Pure Therapy DøDHEIMSGARD FANTOMAS Satanic Art The Director's Cut Imprint 68 them their own. -

3D in Your Face 44 Magnum 5 X 77 (Seventy Seven)

NORMALPROGRAMM, IMPORTE, usw. Eat the heat CD 12,00 District zero CD 29,00 The void unending CD 13,00 Restless and live - Blind rage Dominator CD 18,00 ANCIENT EMPIRE - live in Europe DCD 20,00 Female warrior CD & DVD 18,00 Eternal soldier CD 15,50 Russian roulette CD 12,00 Mermaid MCD 15,50 Other world CD 15,50 Stalingrad CD & DVD18,00 Other world CD & DVD 23,00 The tower CD 15,50 Stayin’ a life DCD 12,00 White crow CD 21,00 When empires fall CD 15,50 The rise of chaos CD 18,50 alle Japan imp. ANGEL DUST ACCID REIGN ALHAMBRA Into the dark past & bonustr. CD 15,50 Awaken CD 15,50 A far cry to you CD 26,00 official rerelease Richtung Within Temptation mit einem Japan imp. To dust you will decay - official guten Schuß Sentenced ALIVE 51 rerelease on NRR CD 15,50 ACCUSER Kissology - an Italian tribute to ANGEL MARTYR Dependent domination CD 15,50 the hottest band in the world CD 15,50 Black book chapter one CD 15,50 Diabolic CD 15,50 ALL SOUL´S DAY ANGELMORA The forlorn divide CD 15,50 Into the mourning CD 15,50 AIRBORN - Lizard secrets CD 15,50 Mask of treason CD 15,50 ACID ALLOY CZAR ANGEL WITCH Acid CD 18,00 Awaken the metal king CD 15,50 `82 revisited CD 15.50 3D IN YOUR FACE Engine beast CD 18,00 Moderater NWoBHM Sound zwischen Angel Witch - deluxe edition DCD 15,50 Faster and faster CD 15,50 Maniac CD 18,00 BITCHES SIN, SARACEN, DEMON, Eine tolle, packende Mischung aus SATANIC RITES gelegen. -

Machine Head from This Day Mp3, Flac, Wma

Machine Head From This Day mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: From This Day Country: Japan Released: 2000 Style: Thrash, Heavy Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1454 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1669 mb WMA version RAR size: 1672 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 809 Other Formats: VOX FLAC VOC MP4 AC3 MP1 AIFF Tracklist 1 From This Day 3:55 2 Desire To Fire (Live) 4:39 3 The Blood, The Sweat, The Tears (Live) 4:36 4 From This Day (Live) 4:29 Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Roadrunner Japan, Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – The All Blacks B.V. Copyright (c) – The All Blacks B.V. Credits Bass – Adam Duce Drums – Dave McClain Guitar – Ahrue Luster Guitar, Vocals – Robert Flynn Lyrics By – Robert Flynn Mixed By – Terry Date (tracks: 1), Toby Wright (tracks: 2 to 4) Music By – Machine Head , Machine Head Producer – Machine Head (tracks: 2 to 4), Ross Robinson (tracks: 1) Recorded By, Engineer – Steve Remote* (tracks: 2 to 4) Notes Tracks 2 to 4 recorded live at Webster Hall, Hartford, CT on Sept. 15, 1999 and exclusive unreleased tracks. CD in slim case comes with OBI strip and a sticker set of the MH logo. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Printed): 4 527583 002451 Barcode (Scanned): 4527583002451 Rights Society: JASRAC Matrix / Runout: RRCY-19018 AH003A Mastering SID Code: IFPI L223 Mould SID Code: IFPI IE08 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Machine From This Day Roadrunner RR 2138-3 RR 2138-3 Netherlands 1999 Head (CD, Maxi) Records Machine From This Day Roadrunner RR 2138-3 RR 2138-3 -

Mailorderliste, Stand 29.11.2015

Mailorderliste, Stand 29.11.2015 CDs / MCDs / LPs ABOMINANT "Upon black horizons" CD 9,00 EUR (Cheapo! Tipp! Import! Schneller Death-Metal mit skandinavischem Einschlag, USA) ENOCHIAN/ISACAARUM "Split" CD 12,50 EUR ABOMINANT "Warblast" CD 11,50 EUR (Out of print Leviathan Rec. Release) (Import! Variabler U.S.-Death-Metal mit melodischem Einschlag) ...And You Will Know Us By The Trail Of Dead " Worlds Apart" CD 4,00 EUR ABOMINATION "Demos" Digi-CD 14,00 EUR (Interscope 2005, 2nd Hand NM/NM) (Demo-Compilation CD, 2013 Doomentia Rec. Digipack Release, new+ Sealed) 1000 YARD STARE "1000 Yard Stare" MCD 4,00 EUR ABOMINATOR "Eternal Conflagration" CD 9,00 EUR (Cheapo! Import! Mischung aus Grind/Death und Hardcore aus den Staaten) (Cheapo! Prügeliger Black/Thrash aus Australien) 1349 "Revelation of the black flame" CD 14,00 EUR ABOMINATOR "Subversives for Lucifer" CD 9,00 EUR (Cheapo! Black Metal from Norway, 2009 Candlelight Release, New+Sealed) (Cheapo! Prügeliger Black/Thrash aus Australien) 1917 "Neo Ritual" CD 9,00 EUR ABOMINATOR/MORNALAND "Prelude to world funeral" CD 7,00 EUR (Import! Death/Black-Metal aus Argentinien) (Cheapo! Oldschooliger Death/Black aus Australien und Schweden) 1917 "Vision" CD 9,00 EUR ABOMINATTION "Doctrine of false" CD 11,00 EUR (Cheapo! Import! Death-Metal aus Argentinien) (Old-Schooliger Death-Metal in Richtung MORBID ANGEL aus Brasilien) 21 LUCIFERS "In the name of" CD 11,50 EUR ABOMINATTION "Rites of eternal hate" CD 11,50 EUR (Import! Melodic Death Metal from Sweden, Pulverized Rec. Release) (Import! Schneller MORBID ANGEL-Like Death-Metal aus Brasilien) 21 LUFICFERS "In the name of..." CD 12,50 EUR ABORT MASTICATION "Orgs" CD 12,50 EUR (Import! Melodic Death/Thrash aus Schweden) (Import! Death/Grind aus Japan) 3 INCHES OF BLOOD "Here waits thy doom" Dig-CD 14,00 EUR ABORTED "Engineering the dead" CD 12,00 EUR (Das neue Album der Heavy Metal Band aus Amiland! Kommt im limitierten DIGI mit Bonustrack!) (Tipp! Re-Release der vergriffenen zweiten Scheibe der holländischen Death-Metaller) 45 Calibre Brain S.