The Early Development of the Washington Dc Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NPS Furm 10-900b OMR Nn. 1024-0018 (Rcviscd March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Public School Buildings of Washington, D. C.,1862-1960 consolidated in a single office and removed from the building regulation functions. Snowden Ashford, who had been appointed Building Inspector in 190 1, was selected as the first Municipal Architect. While private architects continued to be involved in the design work associated with public schools, their design preferences were subservient to those of the Municipal Architect. Snowden Ashford preferred the then fashionable collegiate Gothic and Elizabethan styles for public school buildings. The U. S. Commission of Fine Arts, established in 1910, took a broad view of its responsibilities and sought to extend City Beautiful aesthetics to the design of all public buildings in the nationd capital. Authorized to review District of Columbia school designs, the Commission opposed the Gothic and Elizabethan styles in favor of a uniform standard of school architecture based upon a traditional Colonial style. Ashford prevailed, designing Eastern (1 92 1-23) and Dunbar High Schools (1 91 4-1 6) in collegiate Gothic style. Central High School (1 9 14- 16) was designed by noted St. Louis school architect William B. Ittner also in collegiate Gothic style. Although the Wilson Normal School (1 913) was designed in the collegiate Elizabethan style by Ashford over the Commission's protests, the members influenced the design of the Miner Normal School (1 9 13), by Leon Dessez. The original Elizabethan style submission was changed to a robust Colonial Revival--one of the first in the city. -

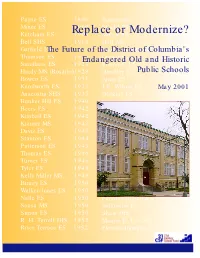

Replace Or Modernize?

Payne ES 1896 Draper ES 1953 Miner ES 1900 Shadd ES 1955 Ketcham ES Replace1909 Moten or ES Modernize1955 ? Bell SHS 1910 Hart MS 1956 Garfield ETheS Future191 0of theSharpe District Health of SE Columbia' 1958 s Thomson ES 191Endangered0 Drew ES Old and 195Historic9 Smothers ES 1923 Plummer ES 1959 Hardy MS (Rosario)1928 Hendley ESPublic 195School9 s Bowen ES 1931 Aiton ES 1960 Kenilworth ES 1933 J.0. Wilson ES May196 12001 Anacostia SHS 1935 Watkins ES 1962 Bunker Hill ES 1940 Houston ES 1962 Beers ES 1942 Backus MS 1963 Kimball ES 1942 C.W. Harris ES 1964 Kramer MS 1943 Green ES 1965 Davis ES 1943 Gibbs ES 1966 Stanton ES 1944 McGogney ES 1966 Patterson ES 1945 Lincoln MS 1967 Thomas ES 1946 Brown MS 1967 Turner ES 1946 Savoy ES 1968 Tyler ES 1949 Leckie ES 1970 Kelly Miller MS 1949 Shaed ES 1971 Birney ES 1950 H.D. Woodson SHS 1973 Walker-Jones ES 1950 Brookland ES 1974 Nalle ES 1950 Ferebee-Hope ES 1974 Sousa MS 1950 Wilkinson ES 1976 Simon ES 1950 Shaw JHS 1977 R. H. Terrell JHS 1952 Mamie D. Lee SE 1977 River Terrace ES 1952 Fletche-Johnson EC 1977 This report is dedicated to the memory of Richard L. Hurlbut, 1931 - 2001. Richard Hurlbut was a native Washingtonian who worked to preserve Washington, DC's historic public schools for over twenty-five years. He was the driving force behind the restoration of the Charles Sumner School, which was built after the Civil War in 1872 as the first school in Washington, DC for African- American children. -

What's in a Name

What’s In A Name: Profiles of the Trailblazers History and Heritage of District of Columbia Public and Public Charter Schools Funds for the DC Community Heritage Project are provided by a partnership of the Humanities Council of Washington, DC and the DC Historic Preservation Office, which supports people who want to tell stories of their neighborhoods and communities by providing information, training, and financial resources. This DC Community Heritage Project has been also funded in part by the US Department of the Interior, the National Park Service Historic Preservation Fund grant funds, administered by the DC Historic Preservation Office and by the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities. This program has received Federal financial assistance for the identification, protection, and/or rehabilitation of historic properties and cultural resources in the District of Columbia. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability in its federally assisted programs. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20240.‖ In brochures, fliers, and announcements, the Humanities Council of Washington, DC shall be further identified as an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. 1 INTRODUCTION The ―What’s In A Name‖ project is an effort by the Women of the Dove Foundation to promote deeper understanding and appreciation for the rich history and heritage of our nation’s capital by developing a reference tool that profiles District of Columbia schools and the persons for whom they are named. -

Burning of Washington

the front door. As the Intelligencer was known to be the Government organ, the printing establishment was put to flame and completely destroyed by the advancing British troops. Revised 06.03.2020 R55/S168 11. DORTHEA (DOLLEY) MADISON (1768–1849) 1 Tingey The wife of President James Madison, she served as First 2 Booth Lady from 1809 until 1817. She first married John Todd, 3 Coombe Jr. (1764–1793), a lawyer who was instrumental in keeping Thornton 4 her father out of bankruptcy. The couple had two sons, John Payne (1792–1852) and William Temple (b./d. 1793). Her husband and their youngest son, William Temple, died in 1793 of a yellow fever. Dolley Todd married James ESTABLISHED 1807 Madison in 1794. Dolley Madison was noted as a gracious Association for the Preservation of hostess, whose sassy, ebullient personality seemed at odds 11 Madison with her Quaker upbringing. Her most lasting achievement Historic Congressional Cemetery was her rescue of valuable treasures, including state papers and a Gilbert Stuart painting of President George Washington from the White House before it was burned 10 Gales WalkingTHE BURNING Tour OF by the British army in 1814. First Lady Madison was 9 Seaton temporarily interred in the Public Vault until she could be 6 Campbell WASHINGTON moved to her final resting place. 5 Watterston istory comes to life in Congressional PUBLIC VAULT Cemetery. The creak and clang of the Crowley 8 7 Pleasanton wrought iron gate signals your arrival into the early decades of our national heritage. Mrs James Madison from an orignal by Gilbert Stuart c1804-1855, LC-USZ62-68175 The English war was a distant quiet thunder on Hthe finger lakes of New York when the residents of the U.S. -

These Separate Schools: Black Politics and Education in Washington, D.C., 1900-1930

These Separate Schools: Black Politics and Education in Washington, D.C., 1900-1930 By Rachel Deborah Bernard A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Waldo Martin, Chair Professor Mark Brilliant Professor Malcolm Feeley Spring 2012 Abstract These Separate Schools: Black Politics and Education in Washington, D.C., 1900-1930 by Rachel Deborah Bernard Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Waldo Martin, Chair “These Separate Schools: Black Politics and Education in Washington, D.C., 1900-1930,” chronicles the efforts of black Washingtonians to achieve equitable public funding and administrative autonomy in their public schools and at Howard University. This project argues that over the course of the early twentieth century, black Washingtonians came to understand their two-pronged goals of administrative autonomy and equitable allocation of resources in both their public schools and at Howard in terms of civil rights. At the turn of the twentieth century, many African Americans in Washington defended their educational institutions as venues for individually demonstrating their own good citizenship and respectability, in other words as means to social and economic uplift. By the 1910s and 1920s, however, they spoke about equal educational opportunity as a civil right, guaranteed to all citizens by the Constitution. Also, while these struggles for educational equality began in the public schools, they were soon taken up by leaders at Howard University and its law school. In addition to educational equality, administrative autonomy was another key part of black Washingtonians’ rights agenda. -

Read Application

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Regist er Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Kingman Park Historic District________________________________ Other names/site number: ______________________________________ Name of related multip le property listing: Spingarn, Browne, Young, Phelps Educational Campus; Spingarn High School; Langston Golf Course and Langston Dwellings ______________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Western Boundary Line is 200-800 Blk 19th Street NE; Eastern Boundary Line is the Anacostia River along Oklahoma Avenue NE; Northern Boundary Line is 19th- 22nd Street & Maryland Avenue NE; Southern Boundary Line is East Capitol Street at 19th- 22nd Street NE. City or town: Washington, DC__________ State: ____DC________ County: ____________ Not For Publicatio n: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

(Volume I. Washington City, D. C., April 2, 1871. Number 4

(VOLUME I. WASHINGTON CITY, D. C., APRIL 2, 1871. NUMBER 4. Tor The Capital. One night some week or so after this mourn- out, with Irish enthusiasm, "Be jabers, and light. Here was a real ghost, and instead of Utie looked viciously up, anger and jealousy Not his sweetheart, who was nothing to him THE AMERICAN SHIP. Pierre Soul<5, A. H. Stovens, Robert C. Winthrop, ADVENT OF SPRING. ful affair, the watchman passing by the door there goes a pacock of the Dimocrasy!" From being driven from further investigation, he de- inflaming his heated face, for, although he had now, not his "honor, which had been only (Song iff the Protectionist.) and Emerson Etlicrldgo. Of course I except the Adown the emerald slopes the suu declines, present company in Congress, for tliat would ne- of the committee-room heard the sound of a that out the Honorable Dawson was known as termined to follow it up. It promised to be no engagement with Miss Rideau, lie conceived vain glory and deceit, not anything but this BT OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES. K'Mld whose cool shadows Summer loves to stay; the great event of his life. himself her future suitor. But some rash earliest, everlasting faith which is ours for- cessitate a catalogue of more than three hundred Kisses with warm red lips the stately pines, voice within. In that lonely place, late at the Peacock of the Democracy, his friends and Ay, tear her tatter'd ensign down! words that he said against the officer were ever, whether we be steadfast or go astray: the names. -

April 03, 2012

CORRESPONDENCE NO. 1 Page 1 of 54 United States Department of the Interior EinAfW OF SUP[f(VISORS NATIONAL PARK SERVICE 1849 C Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20240 luilHAR23 AVI.I.J ' H34(2280) The Honorable Dick Monteith MAR 12 2012 Chairman, Stanislaus County Board ofSupervisors 1010 lOth Street, Suite 6500 Modesto, California 95354 Dear Chairman Monteith: The National Park Service has completed the study ofthe Knight's Ferry Bridge in Stanislaus County, California, for the purpose ofnominating it for designation as a National Historic Landmark. We enclose a copy ofthe nomination. The Landmarks Committee ofthe National Park System Advisory Board will consider the nomination during its next meeting, at the time and place indicated on one ofthe enclosures. This enclosure also specifies how you may comment on the proposed nomination if you so choose. The Landmarks Committee will report on this nomination to the Advisory Board, which in tum will make a recommendation concerning this nomination to the Secretary ofthe Interior, based upon the criteria ofthe National Historic Landmarks Program. Ifyou wish to comment on the nomination, please do so within 60 days ofthe date ofthis letter. After the 60-day period, we will submit the nomination and all comments we have received to the Landmarks Committee. To assist you in considering this matter, we have enclosed a copy ofthe regulations governing the National Historic Landmarks Program. They describe the criteria for designation (§65.4) and include other information on the Program. We are also enclosing a fact sheet that outlines the effects of designation. Sincerely, J. Paul Loether, Chief National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Enclosures CORRESPONDENCE NO. -

Charles Sumner School AND/OR COMMON

Form No. 10-300 ^eM-. \Q^ UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES >:-.«: XvXv*:- INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS _________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC The Charles Sumner School AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Seventeenth and M Streets, NW _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Washington VICINITY OF Walter E. Fauntroy STATE CODE COUNTY CODE District of Columbia 11 District of Columbia 001 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT X-PUBLIC —OCCUPIED .AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM 2LBUILDINGIS) —PRIVATE JiLUNOCCUPIED -COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS -EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE -ENTERTAINMENT _RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS ^LYES: RESTRICTED -GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED -INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY x_OTHER: Vacant [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME District of Columbia Government STREET 8t NUMBER The District Building, Fourteenth and E Streets, NW CITY, TOWN STATE Washington VICINITY OF District of Columbia LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER 6th & D Streets, NW CITY, TOWN STATE Washington District of Columbia [REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE District of Columbia©s Inventory of Historic Sites DATE —FEDERAL X-STATE _COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR Joint District of Columbia/National Capital Planning Commission SURVEY RECORDS Historic Preservation Office_____________________ CITY. TOWN , STATE Washington District of Columbia DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _ EXCELLENT _ DETERIORATED X_UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE GOflp RUINS __ALTERED Mnvpn HATF J£FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Charles Sunnier School (1872) was designed by Washington architect Adolph Cluss and erected by builder Robert I. -

Images for Thesis

ENTERTAINING A NEW REPUBLIC: MUSIC AND THE WOMEN OF WASHINGTON, 1800-1825 by Leah R. Giles A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in American Material Culture Spring 2011 Copyright 2011 Leah R. Giles All Rights Reserved ENTERTAINING A NEW REPUBLIC: MUSIC AND THE WOMEN OF WASHINGTON, 1800-1825 by Leah R. Giles Approved: __________________________________________________________ J. Ritchie Garrison, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ J. Ritchie Garrison, Ph.D. Director of the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Charles G. Riordan, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education PREFACE Before the advent of recorded music (with the exceptions of musical clocks, music boxes, and barrel organs), people had to create sound themselves if they wanted to add a musical component to their entertainment. They could sing and play instruments on their own, or they could bring in outside musicians. This thesis investigates the various ways women in Washington, DC used and played music and musical instruments from 1800 to 1825. As such, it is not intended to be a comprehensive history of music in Washington, DC in the federal era. By focusing on members of elite society, I have been able to take advantage of the rich documentation and objects associated with early Washington‘s middle- and upper-class women. Many of them left behind diaries, letters, and other documents that provide enticing glimpses into their music making. -

Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution

THK ORIGIN OF THE NATIONAL SCIENTIFIC AND EDUCA- TIONAL INSTITUTIONS OF THE UNITED STATES. GEORGE BROWN GOODE, Assisiajit Scar/ary, Siiiit/iso)n'a}i Institniion, i)i cliarcre of t/ic U. S. National Museum. 263 THE ORIGIN OF THI- NATIONAL SCIENTIFIC AND FT)UCA- TIONAL INSTITUTIONS OF THIi UNITED STATES.' By Gkorgk Brown Goodr, Assisiattt Sccir/an', S)//i//!So>n'a>/ Iustitutio)i, in chargf of the ('. S. A\i/io)iaI 3f/ISflllll. ' ' ' ' Early in the seventeenth centur}-, ' we are told, ' the great Mr. Boyle, Bishop Wilkins, and several other" learned men proposed to leave Eng- land and establish a societ}' for promoting knowledge in the new colon}' [of Connecticut] , of which Mr. Winthrop,"" their intimate friend and a.sso- ciate, was appointed governor." "Such men," wrote the historian, "were too valuable to lose from Great Britain, and Charles the Second having taken them under his pro- tection in 1 66 1, the society was there established, and received the title of The Royal Society of London." ^ For more than a hundred years this society' was for our country what it still is for the British colonies throughout the world—a central and national .scientiiic organization. All Americans eminent in science were on its list of Fellows, among them Cotton Mather, the three Winthrops, Iiowdoin, and Paul Dudle}^ in New England; Franklin, Rittenhou.se, and Morgan, in Penns3dvania; Banister, Clayton, Mitchell, and Byrd, in Vir- ginia; and Garden and Williamson in the Carolinas, while in its Philo- sophical Transactions were published the only records of American research." 'A paper presented before the American Historical Societj' at the meeting held in Washington in 1889, and revi.sed and corrected by the author to July 15, 1890.