A Statistical Account of Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIPE-012270-Contents.Pdf

SELECTIONS FROM OFFICIAL LETTERS AND DOCUMENTS RELATING TO THE UfE OF RAJA RAMMOHUN ROY VOL. I EDITED BY lW BAHADUR RAMAPRASAD CHANDA, F.R.A.S.B. L.u Supmnteml.nt of lhe ArchteO!ogit:..S Section. lnd;.n MMe~~m, CUct<lt.t. AND )ATINDRA KUMAR MAJUMDAR, M.A., Ph.D. (LoNDON), Of the Middk Temple, 11uris~er-M-Ltw, ddfJOcote, High Court, C41Cflll4 Sometime Professor of Pb.Josophy. Presidency College, C..Scutt.t. With an Introductory Memoir CALCUTIA ORIENTAL BOOK AGENCY 9> PANCHANAN GHOSE LANE, CALCUTTA Published in 1938 Printed and Published by J. C. Sarkhel, at the Calcutta Oriental Press Ltd., 9, Pancb&nan Ghose Lane, Calcutta. r---~-----~-,- 1 I I I I I l --- ---·~-- ---' -- ____j [By courtesy of Rammohun Centenary Committee] PREFACE By his refor~J~ing activities Raja Rammohun Roy made many enemies among the orthodox Hindus as well as orthodox Christians. Some of his orthodox countrymen, not satis· fied with meeting his arguments with arguments, went to the length of spreading calumnies against him regarding his cha· racter and integrity. These calumnies found their way into the works of som~ of his Indian biographers. Miss S, D. Collet has, however, very ably defended the charact~ of the Raja against these calumniet! in her work, "The Life and Letters of Raja Rammohun Roy." But recently documents in the archives of the Governments of Bengal and India as well as of the Calcutta High Court were laid under contribution to support some of these calumnies. These activities reached their climax when on the eve of the centenary celebration of the death of Raja Rammohun Roy on the 27th September, 1933, short extracts were published from the Bill of Complaint of a auit brought against him in the Supreme Court by his nephew Govindaprasad Roy to prove his alleged iniquities. -

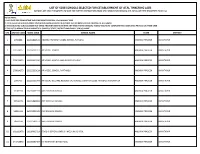

List of 6038 Schools Selected for Establishment of Atal Tinkering

LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. LAST DATE FOR COMPLETING THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS : 31st JANUARY 2020 2. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST OPEN A NEW BANK ACCOUNT IN A PUBLIC SECTOR BANK FOR THE PURPOSE OF ATL GRANT. 3. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST NOT SHARE THEIR INFORMATION WITH ANY THIRD PARTY/ VENDOR/ AGENT/ AND MUST COMPLETE THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS ON THEIR OWN. 4. THIS LIST IS ARRANGED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER OF STATE, DISTRICT AND FINALLY SCHOOL NAME. S.N. ATL UID CODE UDISE CODE SCHOOL NAME STATE DISTRICT 1 2760806 28222800515 ANDHRA PRADESH MODEL SCHOOL PUTLURU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 2 132314217 28224201013 AP MODEL SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 3 574614473 28223600320 AP MODEL SCHOOL AND JUNIOR COLLEGE ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 4 278814373 28223200124 AP MODEL SCHOOL RAPTHADU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 5 2995459 28222500704 AP SOCIAL WELFARE RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL JUNIOR COLLEGE FOR GIRLS KURUGUNTA ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 6 13701194 28220601919 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 7 15712075 28221890982 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 8 56051196 28222301035 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 9 385c1160 28221591153 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 10 102112978 28220902023 GOOD SHEPHERD ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 11 243715046 28220590484 K C NARAYANA E M SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. -

An Analysis of Trade and Commerce in the Princely States of Nayagarh District (1858-1947)

Odisha Review April - 2015 An Analysis of Trade and Commerce in the Princely States of Nayagarh District (1858-1947) Dr. Saroj Kumar Panda The present Nayagarh District consists of Ex- had taken rapid strides. Formerly the outsiders princely states of Daspalla, Khandapara, only carried on trade here. But of late, some of Nayagarh and Ranpur. The chief occupation of the residents had turned traders. During the rains the people of these states was agriculture. When and winter, the export and import trade was the earnings of a person was inadequate to carried on by country boats through the river support his family, he turned to trade to Mahanadi which commercially connected the supplement his income. Trade and commerce state with the British districts, especially with attracted only a few thousand persons of the Cuttack and Puri. But in summer the trade was Garjat states of Nayagarh, Khandapara, Daspalla carried out by bullock carts through Cuttack- and Ranpur. On the other hand, trade and Sonepur Road and Jatni-Nayagarh-Daspalla commerce owing to miserable condition of Road. communications and transportations were of no importance for a long time. Development of Rice, Kolthi, Bell–metal utensils, timbers, means of communication after 1880 stimulated Kamalagundi silk cloths, dying materials produced the trade and commerce of the states. from the Kamalagundi tree, bamboo, mustard, til, molasses, myrobalan, nusevomica, hide, horns, The internal trade was carried on by means bones and a lot of minor forest produce, cotton, of pack bullocks, carts and country boats. The Mahua flower were the chief articles of which the external trade was carried on with Cuttack, Puri Daspalla State exported. -

Globally, the Travel, Tourism and Hospitality Industry Is One of The

Globally, the travel, tourism and hospitality industry is one of the largest service industries in terms of revenue generation and foreign exchange earnings, contributing over 9% to global GDP. It is also one of the largest employment generators in the world. An estimated 235 million people work directly or in related sectors, accounting for more than 8% of global employment. The industry had witnessed a slowdown in 2009 on account of the global financial meltdown. Low business and consumer confidence along with other concerns such as availability of credit, exchange rate fluctuation, H1N1 virus, terrorist attacks, etc aggravated the situation. Nevertheless, the industry witnessed a revival in the last quarter of 2009, largely led by recovery in Asia and the Middle East. India is one of the fastest growing tourism markets in the world today. Various policy measures undertaken by the Government have aided the Indian travel, tourism and hospitality industry¶s growth. Concerted efforts by both the private and public sectors will enable us position India as a global brand to take advantage of the burgeoning global travel trade and the vast untapped potential of India as a major tourist destination. Some of trends covered in this publication include: y India¶s travel and tourism industry directly and indirectly is expected to account for around 8.6% of the country¶s GDP in 2010. The direct contribution of the travel and tourism industry is expected to be around 3.1% of total GDP. y Foreign tourist arrivals in the country in 2009 were adversely impacted by the global economic slowdown and threat of terror attacks. -

Details of Para Legal Volunteers of District Legal Services Authority, Angul

DETAILS OF PARA LEGAL VOLUNTEERS OF DISTRICT LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY, ANGUL Sl No. Name of the PLV Age Gender Mobile Number Date of Empanelled in empanelment DLSA/ TLSC 1 Kausalya Muduli 38 Years Female 8658299890 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 2 Abanti Muduli 31 Years Female 8018391319 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 3 Jhunubala Sahu 38 Years Female 8018850439 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 4 Bijayeeni Sahu 44 Years Female 8658918552 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul Sarmistha Biswal 38 Years Female 9776454333 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 5 Sanghamitra Naik 23 Years Female 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 6 9556512700 Bikash Sasmal 23 Years Male 7077020304 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 7 Subhadra Sethi 29 Years Female 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 8 9348910431 9 Bibhu Charan Sahoo 40 Years Male 7894478755 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 10 Dipun Kumar Barik 25 Years Male 9938689679 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 11 Gopabandhu Naik 23 Years Male 7894548938 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 12 Puspanjali Pal 44 Years Female 9438072036 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul Jagannath Sahoo, Jagyaseni 45 Years Transgender 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 13 7894323217 Kinar 14 Kunirani Roul 58 Years Female 9078128575 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 15 Jhilli Behera 38 Years Female 9777916411 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 16 Bharati Garanaik 54 Years Female 9556529612 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul Dr. Satya Narayan Singh 60 Years Male 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 17 9853163931 Samant 18 Manasi Samal 37 Years Female 7504852540 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 19 Alekha Pradhan 36 Years Male 9337192960 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 20 Sita Pradhan 39 Years Female 9178409067 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 21 Puspalata Pradhan 34 Years Female 9078491627 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 22 Santilata Sahu 58 Years Female 9438327375 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul Askara sahoo 45 Years Female 8280417749 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 23 24 Bisikesan Naik 48 Years Male 8658400859 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 25 Ashok Kumar Pradhan 41 Years Male 9439349301 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 26 Prafulla Ch. -

Abdul En Bangladés Aguri En Bangladés Ahmadi En Bangladés

Ore por los No-Alcanzados Ore por los No-Alcanzados Abdul en Bangladés Aguri en Bangladés País: Bangladés País: Bangladés Etnia: Abdul Etnia: Aguri Población: 27,000 Población: 1,000 Población Mundial: 63,000 Población Mundial: 515,000 Idioma Principal: Bengali Idioma Principal: Bengali Religión Principal: Islam Religión Principal: Hinduismo Estatus: Menos Alcanzado Estatus: Menos Alcanzado Seguidores de Cristo: Pocos, menos del 2% Seguidores de Cristo: Pocos, menos del 2% Biblia: Biblia Biblia: Biblia www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net "Proclamen su gloria entre las naciones" Salmos 96:3 "Proclamen su gloria entre las naciones" Salmos 96:3 Ore por los No-Alcanzados Ore por los No-Alcanzados Ahmadi en Bangladés Akhandji en Bangladés País: Bangladés País: Bangladés Etnia: Ahmadi Etnia: Akhandji Población: 2,100 Población: 500 Población Mundial: 167,000 Población Mundial: 500 Idioma Principal: Bengali Idioma Principal: Bengali Religión Principal: Islam Religión Principal: Islam Estatus: Menos Alcanzado Estatus: Menos Alcanzado Seguidores de Cristo: Pocos, menos del 2% Seguidores de Cristo: Pocos, menos del 2% Biblia: Biblia Biblia: Biblia www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net "Proclamen su gloria entre las naciones" Salmos 96:3 "Proclamen su gloria entre las naciones" Salmos 96:3 Ore por los No-Alcanzados Ore por los No-Alcanzados Ansari en Bangladés Arakanés en Bangladés País: Bangladés País: Bangladés Etnia: Ansari Etnia: Arakanés Población: 1,241,000 Población: 195,000 Población Mundial: 16,505,000 Población Mundial: 241,000 -

Citizen Forum of WODC

DATA WODC SINCE INCEPTION TILL 05.08.2016 Project Released Sl No ID DISTRICT Executing Agency Name of the Project Amount Year Completion of Bauribandha Check Dam & Retaining Wall B.D.O., at Angapada, Angapada G.P. of 1 20350 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 500000 2014-2015 Constn. of Bridge Between Budiabahal to Majurkachheni, B.D.O., Kadalimunda G.P. of 2 20238 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 500000 2014-2015 Constn. of Main Building Ambapal Homeopathy B.D.O., Dispensary, Ambapal G. P. of 3 20345 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 500000 2014-2015 Completion of Addl. Class Room of Lunahandi High School Building, Lunahandi 4 19664 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. G.P. of Athmallik Block 300000 2014-2015 Constn. of Gudighara Bhagabat Tungi at Tentheipali, Kudagaon G.P. of 5 19264 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. Athmallik Block 300000 2014-2015 Constn. of Kothaghara at Tentheipali, Kudagaon G.P. of 6 19265 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. Athmallik Block 300000 2014-2015 Completion of Building and Water Supply to Radhakrishna High School, B.D.O., Pursmala, Urukula G.P. of 7 19020 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 700000 2014-2015 Completion of Pitabaligorada B.D.O., Bridge, Urukula G.P. of 8 19019 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 900000 2014-2015 Constn. of Bridge at Ghaginallah in between Ghanpur Serenda Road, B.D.O., Urukula G.P. of Kishorenagar 9 19018 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Block 1000000 2014-2015 Completion of Kalyan Mandap at Routpada, Kandhapada G.P. 10 19656 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. of Athmallik Block 200000 2014-2015 Constn. of Bhoga Mandap inside Maheswari Temple of 11 19659 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. -

REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932'

EAST INDIA (CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS) REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932' Presented by the Secretary of State for India to Parliament by Command of His Majesty July, 1932 LONDON PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from H^M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses Adastral House, Kingsway, London, W.C.2; 120, George Street, Edinburgh York Street, Manchester; i, St. Andrew’s Crescent, Cardiff 15, Donegall Square West, Belfast or through any Bookseller 1932 Price od. Net Cmd. 4103 A House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. The total cost of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) 4 is estimated to be a,bout £10,605. The cost of printing and publishing this Report is estimated by H.M. Stationery Ofdce at £310^ House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page,. Paras. of Members .. viii Xietter to Frim& Mmister 1-2 Chapter I.—^Introduction 3-7 1-13 Field of Enquiry .. ,. 3 1-2 States visited, or with whom discussions were held .. 3-4 3-4 Memoranda received from States.. .. .. .. 4 5-6 Method of work adopted by Conunittee .. .. 5 7-9 Official publications utilised .. .. .. .. 5. 10 Questions raised outside Terms of Reference .. .. 6 11 Division of subject-matter of Report .., ,.. .. ^7 12 Statistic^information 7 13 Chapter n.—^Historical. Survey 8-15 14-32 The d3masties of India .. .. .. .. .. 8-9 14-20 Decay of the Moghul Empire and rise of the Mahrattas. -

GIPE-017791-Contents.Pdf (2.126Mb)

OFFICIAL AG~NTS . FOR THE SALE OF GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. In India. MESSRS. THA.CXBK, SPINK & Co., Calcutta and Simla. · MESSRS. NEWKA.N & Co., Calcutta. MESSRS. HIGGINBOTHA.M & Co., Madras. MESSRS. THA.Ci:BB & Co., Ln., Bombay. MESSRS . .A.. J. CoHBRIDGB & Co., Bombay. THE SUPERINTENDENT, .A.M:ERICA.N BA.l'TIS'l MISSION PRESS, Ran~toon. Mas. R.l.DHA.BA.I ATKARA.M SA.aooN, Bombay. llissas. R. CA.HBRA.Y & Co., Calcutta. Ru SA.HIB M. GuL&B SINGH & SoNs, Proprietors of the Mufid.i-am Press, Lahore, Punjab. MEsSRS. THoMPSON & Co., Madras. MESSRS. S. MuRTHY & Co., Madras. MESSRS. GoPA.L NA.RA.YEN & Co., Bombay. AhssRs. B. BuiERlEB & Co., 25 Cornwallis Street,· Calcutta. MBssas. S. K. LA.HlRI & Co., Printers and Booksellers, College Street, Calcutta. MESSRS. V. KA.LYA.NA.RUIA. IYER & Co., Booksellers, &c., Madras. MESSRS. D. B. TA.RA.POREVA.LA., SoNs & Co., Booksellers, Bombay. MESSRS. G. A; NA.TESON & Co., Madras. MR. N. B. MA.THUR, Superintendent, Nazair Kanum Hind Press, AJlahabad. - TnB CA.LCUTTA. ScHOOL Boox SociETY. MR. SUNDER PA.NDURA.NG, Bombay. MESSRs. A.M. A.ND J. FERGusoN, Ceylon. MEssRsrTEMPI.B & Co., Madras. · MEssRs. CoHBRIDGB & Co., Madras •. MESSRS. A. R. PILLA.I & Co., Trivandrum. ~bssRs. A. CHA.ND &-Co., Lahore, Punjab. ·- .·· BA.Bu S. C. T.A.LUXDA.B, Proprietor, Students & Co., Ooocli Behar. ------' In $ng~a»a.~ AIR. E. A. • .ARNOLD, 41 & 43 -M.ddo:x:• Street, Bond Street, London, W. , .. MESSRS. CoNSTA.BLB & Co., 10 Orange· Sheet, Leicester Square, London, W. C. , MEssRs. GaiNDLA.Y & Co., 64. Parliament Street, London, S. -

Officename a G S.O Bhubaneswar Secretariate S.O Kharavela Nagar S.O Orissa Assembly S.O Bhubaneswar G.P.O. Old Town S.O (Khorda

pincode officename districtname statename 751001 A G S.O Khorda ODISHA 751001 Bhubaneswar Secretariate S.O Khorda ODISHA 751001 Kharavela Nagar S.O Khorda ODISHA 751001 Orissa Assembly S.O Khorda ODISHA 751001 Bhubaneswar G.P.O. Khorda ODISHA 751002 Old Town S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751002 Harachandi Sahi S.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Kedargouri S.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Santarapur S.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Bhimatangi ND S.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Gopinathpur B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Itipur B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Kalyanpur Sasan B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Kausalyaganga B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Kuha B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Sisupalgarh B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Sundarpada B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Bankual B.O Khorda ODISHA 751003 Baramunda Colony S.O Khorda ODISHA 751003 Suryanagar S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751004 Utkal University S.O Khorda ODISHA 751005 Sainik School S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751006 Budheswari Colony S.O Khorda ODISHA 751006 Kalpana Square S.O Khorda ODISHA 751006 Laxmisagar S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751006 Jharapada B.O Khorda ODISHA 751006 Station Bazar B.O Khorda ODISHA 751007 Saheed Nagar S.O Khorda ODISHA 751007 Satyanagar S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751007 V S S Nagar S.O Khorda ODISHA 751008 Rajbhawan S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751009 Bapujee Nagar S.O Khorda ODISHA 751009 Bhubaneswar R S S.O Khorda ODISHA 751009 Ashok Nagar S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751009 Udyan Marg S.O Khorda ODISHA 751010 Rasulgarh S.O Khorda ODISHA 751011 C R P Lines S.O Khorda ODISHA 751012 Nayapalli S.O Khorda ODISHA 751013 Regional Research Laboratory -

The Chitrakars in Naya: Emotion and the Ways of Remembrance

Words and Silences is the Digital Edition Journal of the International Oral History Association. It includes articles from a wide range of disciplines and is a means for the professional community to share projects and current trends of oral history from around the world. http://ioha.org Online ISSN 2222-4181 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA Words and Silences March 2018 “Oral History and Emotions” The Chitrakars in Naya: Emotion and the Ways of Remembrance Reeti Basu Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India [email protected] Introduction The Patuas are a community of painters living in the eastern part of India, West Bengal. Patuas or Chitrakars have been practicing patachitra or patashilpa for centuries. Patachitra or patashilpa is a form of scroll painting. Their diverse repertoire includes tales from Hindu mythology, tribal folklore, as well as Islamic tradition. They paint their stories on long scrolls and sing, as the scroll is unrolled frame by frame. The community of Patuas is spread over many districts of pre-partitioned Bengal: Mursidabad, Bankura, South Twenty-four-Parganas etc (including present-day Bangladesh). Today there are only a few practicing Patuas. Most of them live in the Indian districts of Medinipur and Birbhum (West Bengal). Even in Medinipur, the Patuas are giving up their art and taking to carpentry and farming. The market for pats has shrunk and the income has declined. -

Appellate Side DAILY CAUSELIST for Friday the 29Th January 2021

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Friday, 29th of January, 2021 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HON'BLE CHIEF JUSTICE THOTTATHIL B. 1 On 29-01-2021 1 RADHAKRISHNAN 1 DB -I At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 37 On 29-01-2021 2 12 HON'BLE JUSTICE MD. NIZAMUDDIN DB - III At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 29-01-2021 3 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE MD. NIZAMUDDIN DB - III At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 2 On 29-01-2021 4 15 HON'BLE JUSTICE BIBEK CHAUDHURI DB At 02:00 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 2 On 29-01-2021 5 16 HON'BLE JUSTICE KAUSIK CHANDA DB- IV At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 29-01-2021 6 27 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAVI KRISHAN KAPUR DB At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 29-01-2021 7 28 HON'BLE JUSTICE ANIRUDDHA ROY DB - V At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 11 On 29-01-2021 8 30 HON'BLE JUSTICE HIRANMAY BHATTACHARYYA DB - VI At 10:45 AM 11 On 29-01-2021 9 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 33 SB At 02:00 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 28 On 29-01-2021 10 36 HON'BLE JUSTICE TIRTHANKAR GHOSH DB - VII At 10:45 AM 28 On 29-01-2021 11 HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 49 SB - I At 03:00 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 4 On 29-01-2021 12 51 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUVRA GHOSH DB - VIII At 10:45 AM 4 On 29-01-2021 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 54 SB - II At 03:00 PM 6 On 29-01-2021 14 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE 58 SB At 10:45 AM 38 On 29-01-2021 15 HON'BLE JUSTICE ASHIS KUMAR CHAKRABORTY 66 SB - II At 10:45 AM 9 On 29-01-2021 16 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 67 SB - III At 10:45 AM 13 On 29-01-2021 17 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 70 SB - IV At 10:45 AM SL NO.