Soybean Aphids in Iowa—2007 by Marlin E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soybean Mosaic Virus

-- CALIFORNIA D EP AUM ENT OF cdfa FOOD & AGRICULTURE ~ California Pest Rating Proposal for Soybean mosaic virus Current Pest Rating: none Proposed Pest Rating: C Kingdom: Orthornavirae; Phylum: Pisuviricota Class: Stelpaviricetes; Order: Patatavirales Family: Potyviridae; Genus: Potyvirus Comment Period: 6/15/2020 through 7/30/2020 Initiating Event: On August 9, 2019, USDA-APHIS published a list of “Native and Naturalized Plant Pests Permitted by Regulation”. Interstate movement of these plant pests is no longer federally regulated within the 48 contiguous United States. There are 49 plant pathogens (bacteria, fungi, viruses, and nematodes) on this list. California may choose to continue to regulate movement of some or all these pathogens into and within the state. In order to assess the needs and potential requirements to issue a state permit, a formal risk analysis for Soybean mosaic virus is given herein and a permanent pest rating is proposed. History & Status: Background: The family Potyviridae contains six genera and members are notable for forming cylindrical inclusion bodies in infected cells that can be seen with light microscopy. Of the six genera, the genus Potyvirus contains by far the highest number of important plant pathogens Named after Potato virus Y, “pot-y-virus” particles are flexuous and filamentous and composed of ssRNA and a protein coat. Most diseases caused by potyviruses appear primarily as mosaics, mottling, chlorotic rings, or color break on foliage, flowers, fruits, and stems. Many cause severe stunting of young plants and drastically reduced yields with leaf, fruit, and stem malformations, fruit drop, and necrosis (Agrios, 2005). Soybean is one of the most important sources of edible oil and proteins for people and animals, and a source of biofuel. -

Role of Soybean Mosaic Virus–Encoded Proteins in Seed and Aphid Transmission in Soybean

Virology e-Xtra* Role of Soybean mosaic virus–Encoded Proteins in Seed and Aphid Transmission in Soybean Sushma Jossey, Houston A. Hobbs, and Leslie L. Domier First and second authors: Department of Crop Sciences, and third author: United States Department of Agriculture–Agricultural Research Service, Department of Crop Sciences, University of Illinois, Urbana 61801. Accepted for publication 2 March 2013. ABSTRACT Jossey, S., Hobbs, H. A., and Domier, L. L. 2013. Role of Soybean transmissibility of the two SMV isolates, and helper component pro- mosaic virus–encoded proteins in seed and aphid transmission in teinase (HC-Pro) played a secondary role. Seed transmission of SMV was soybean. Phytopathology 103:941-948. influenced by P1, HC-Pro, and CP. Replacement of the P1 coding region of SMV 413 with that of SMV G2 significantly enhanced seed transmis- Soybean mosaic virus (SMV) is seed and aphid transmitted and can sibility of SMV 413. Substitution in SMV 413 of the two amino acids cause significant reductions in yield and seed quality in soybean (Glycine that varied in the CPs of the two isolates with those from SMV G2, G to max). The roles in seed and aphid transmission of selected SMV-encoded D in the DAG motif and Q to P near the carboxyl terminus, significantly proteins were investigated by constructing mutants in and chimeric reduced seed transmission. The Q-to-P substitution in SMV 413 also recombinants between SMV 413 (efficiently aphid and seed transmitted) abolished virus-induced seed-coat mottling in plant introduction 68671. and an isolate of SMV G2 (not aphid or seed transmitted). -

Viral Diseases of Soybeans

SoybeaniGrow BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES Chapter 60: Viral Diseases of Soybeans Marie A.C. Langham ([email protected]) Connie L. Strunk ([email protected]) Four soybean viruses infect South Dakota soybeans. Bean Pod Mottle Virus (BPMV) is the most prominent and causes significant yield losses. Soybean Mosaic Virus (SMV) is the second most commonly identified soybean virus in South Dakota. It causes significant losses either in single infection or in dual infection with BPMV. Tobacco Ringspot Virus (TRSV) and Alfalfa Mosaic Virus (AMV) are found less commonly than BPMV or SMV. Managing soybean viruses requires that the living bridge of hosts be broken. Key components for managing viral diseases are provided in Table 60.1. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the symptoms, vectors, and management of BPMV, SMV, TRSV, and AMV. Table 60.1. Key components to consider in viral management. 1. Viruses are obligate pathogens that cannot be grown in artificial culture and must always pass from living host to living host in what is referred to as a “living or green” bridge. 2. Breaking this “living bridge” is key in soybean virus management. a. Use planting dates to avoid peak populations of insect vectors (bean leaf beetle for BPMV and aphids for SMV). b. Use appropriate rotations. 3. Use disease-free seed, and select tolerant varieties when available. 4. Accurate diagnosis is critical. Contact Connie L. Strunk for information. (605-782-3290 or [email protected]) 5. Fungicides and bactericides cannot be used to manage viral problems. 60-541 extension.sdstate.edu | © 2019, South Dakota Board of Regents What are viruses? Viruses that infect soybeans present unique challenges to soybean producers, crop consultants, breeders, and other professionals. -

Characterization of Seed Transmission of Soybean Mosaic Virus in Soybean

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-24-2015 12:00 AM Characterization of Seed Transmission of Soybean Mosaic Virus in Soybean Tanvir Bashar The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Aiming Wang The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Dr. Mark Bernards The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Biology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Science © Tanvir Bashar 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Virology Commons Recommended Citation Bashar, Tanvir, "Characterization of Seed Transmission of Soybean Mosaic Virus in Soybean" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2791. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2791 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARACTERIZATION OF SEED TRANSMISSION OF SOYBEAN MOSAIC VIRUS IN SOYBEAN (Thesis format: Monograph) by TANVIR BASHAR Graduate Program in Biology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Tanvir Bashar 2015 ABSTRACT Infection by Soybean mosaic virus (SMV) is recognized as a serious, long-standing threat in most soybean (Glyince max (L.)Merr.) producing areas of the world. The aim of this work was to understand how SMV transmits from infected soybean maternal tissues to the next generation by investigating the possible routes and amounts of seed transmission of SMV. -

Soybean Aphid Establishment in Georgia

Soybean Aphid Establishment in Georgia R. M. McPherson, Professor, Entomology J.C. Garner, Research Station Superintendent, Georgia Mountain Research and Education Center, Blairsville, GA P. M. Roberts, Extension Entomologist - Cotton & Soybean The soybean aphid, Aphis glycines Matsumura, has (nymphs) through parthenogenesis (reproduction by direct become a major new invasive pest species in North America. growth of egg-cells without male fertilization). Several It was first detected on Wisconsin soybeans during the generations of both winged and wingless female aphids are summer of 2000. By the end of the 2001 growing season, produced on soybeans during the summer. As soybeans begin soybean aphid populations were observed from New York to mature, both male and female winged aphids are produced. westward to Ontario, Canada, the Dakotas, Nebraska They migrate back to buckthorn where they mate and the and Kansas and southward to Missouri, Kentucky and females lay the overwintering eggs, thus starting the annual Virginia. By 2009 it had been detected in most of the cycle all over again. soybean-producing states in the U.S. On September 10 and October 1, 2002, during monthly field sampling of soybeans at the Georgia Mountain Research and Education Center in Blairsville, Ga., several small colonies of soybean aphids (eight to 10 aphids per leaf) were collected. Aphid identification was verified by Susan Halbert, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, Gainesville, Fla. Soybean aphids have been observed on soybeans in Union County, Ga., (Blairsville) Photo 1. Colony of soybean aphids on a every year since 2002 and in several other Georgia counties in soybean leaf. -

Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management Kelley Tilmon ([email protected]) Buyung Hadi ([email protected]) The soybean aphid (Aphis glycines) is a significant insect pest of soybean in the North Central region of the U.S., and if left untreated can reduce regional production values by as much as $2.4 billion annually (Song et al., 2006). The soybean aphid is an invasive pest that is native to eastern Asia, where soybean was first domesticated. The pest was first detected in the U.S. in 2000 (Tilmon et al., 2011) and in South Dakota in 2001. It quickly spread across 22 states and three Canadian provinces. Soybean aphid populations have the potential to increase rapidly and reduce yields (Hodgson et al., 2012). This chapter reviews the identification, biology and management of soybean aphid. Treatment thresholds, biological control, host plant resistance, and other factors affecting soybean aphid populations will also be discussed. Table 35.1 provides suggestions to lessen the financial impact of aphid damage. Table 35.1. Keys to reducing economic losses from aphids. • Use resistant aphid varieties; several are now available. • Monitor closely because populations can increase rapidly. • Soybean near buckthorn should be scouted first. • Adults can be winged or wingless • Determine if your field contains any biocontrol agents (especially lady beetles). • Control if the population exceeds 250 aphids/plant. CHAPTER 35: Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management 1 Description Adult soybean aphids can occur in either winged or wingless forms. Wingless aphids are adapted to maximize reproduction, and winged aphids are built to disperse and colonize other locations. -

![Genetic Analysis of Soybean Mosaic Virus (SMV) Resistance Genes in Soybean [Glycine Max (L.) Merr.] Mariola Klepadlo University of Arkansas, Fayetteville](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7212/genetic-analysis-of-soybean-mosaic-virus-smv-resistance-genes-in-soybean-glycine-max-l-merr-mariola-klepadlo-university-of-arkansas-fayetteville-1097212.webp)

Genetic Analysis of Soybean Mosaic Virus (SMV) Resistance Genes in Soybean [Glycine Max (L.) Merr.] Mariola Klepadlo University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 Genetic Analysis of Soybean Mosaic Virus (SMV) Resistance Genes in Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] Mariola Klepadlo University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Plant Breeding and Genetics Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons Recommended Citation Klepadlo, Mariola, "Genetic Analysis of Soybean Mosaic Virus (SMV) Resistance Genes in Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.]" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1451. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1451 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Genetic Analysis of Soybean Mosaic Virus (SMV) Resistance Genes in Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Crop, Soil, and Environmental Sciences by Mariola Klepadlo University of Szczecin, Poland Bachelor of Science in Biotechnology, 2007 University of Szczecin, Poland Master of Science in Biotechnology, 2009 The Mediterranean Agronomic Institute of Chania, Greece Master of Science in Horticultural Genetics and Biotechnology, 2011 May 2016 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ___________________________________ Dr. Pengyin Chen Dissertation Director ____________________________________ ___________________________________ Dr. Kenneth L. Korth Dr. Richard E. Mason Committee Member Committee Member ____________________________________ ___________________________________ Dr. Vibha Srivastava Dr. Ioannis E. Tzanetakis Committee Member Committee Member ABSTRACT Soybean mosaic virus (SMV) causes the most serious viral disease in soybean worldwide. -

Tracking the Role of Alternative Prey in Soybean Aphid Predation

Molecular Ecology (2007) 16, 4390–4400 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03482.x TrackingBlackwell Publishing Ltd the role of alternative prey in soybean aphid predation by Orius insidiosus: a molecular approach JAMES D. HARWOOD,* NICOLAS DESNEUX,†§ HO JUNG S. YOO,†¶ DANIEL L. ROWLEY,‡ MATTHEW H. GREENSTONE,‡ JOHN J. OBRYCKI* and ROBERT J. O’NEIL† *Department of Entomology, University of Kentucky, S-225 Agricultural Science Center North, Lexington, Kentucky 40546-0091, USA, †Department of Entomology, Purdue University, Smith Hall, 901 W. State Street, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907-2089, USA, ‡USDA-ARS, Invasive Insect Biocontrol and Behavior Laboratory, BARC-West, Beltsville, Maryland 20705, USA Abstract The soybean aphid, Aphis glycines (Hemiptera: Aphididae), is a pest of soybeans in Asia, and in recent years has caused extensive damage to soybeans in North America. Within these agroecosystems, generalist predators form an important component of the assemblage of natural enemies, and can exert significant pressure on prey populations. These food webs are complex and molecular gut-content analyses offer nondisruptive approaches for exam- ining trophic linkages in the field. We describe the development of a molecular detection system to examine the feeding behaviour of Orius insidiosus (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae) upon soybean aphids, an alternative prey item, Neohydatothrips variabilis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), and an intraguild prey species, Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Specific primer pairs were designed to target prey and were used to examine key trophic connections within this soybean food web. In total, 32% of O. insidiosus were found to have preyed upon A. glycines, but disproportionately high consumption occurred early in the season, when aphid densities were low. -

Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management

SoybeaniGrow BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES Chapter 35: Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management Kelley Tilmon Buyung Hadi The soybean aphid (Aphis glycines) is a significant insect pest of soybean in the North Central region of the U.S., and if left untreated can reduce regional production values by as much as $2.4 billion annually (Song et al., 2006). The soybean aphid is an invasive pest that is native to eastern Asia, where soybean was first domesticated. The pest was first detected in the U.S. in 2000 (Tilmon et al., 2011) and in South Dakota in 2001. It quickly spread across 22 states and three Canadian provinces. Soybean aphid populations have the potential to increase rapidly and reduce yields (Hodgson et al., 2012). This chapter reviews the identification, biology, and management of soybean aphid. Treatment thresholds, biological control, host plant resistance, and other factors affecting soybean aphid populations will also be discussed. Table 35.1 provides suggestions to lessen the financial impact of aphid damage. Table 35.1. Keys to reducing economic losses from aphids. • Use resistant aphid varieties; several are now available. • Monitor closely because populations can increase rapidly. • Soybean near buckthorn should be scouted first. • Adults can be winged or wingless • Determine if your field contains any biocontrol agents (especially lady beetles). • Control if the population exceeds 250 aphids/plant. 35-293 extension.sdstate.edu | © 2019, South Dakota Board of Regents Description Adult soybean aphids can occur in either winged or wingless forms. Wingless aphids are adapted to maximize reproduction, and winged aphids are built to disperse and colonize other locations. -

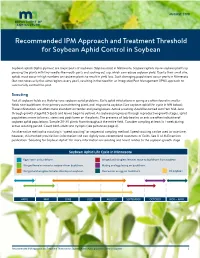

Recommended IPM Approach and Treatment Threshold for Soybean Aphid Control in Soybean

AUGUST 2018 Recommended IPM Approach and Treatment Threshold for Soybean Aphid Control in Soybean Soybean aphids (Aphis glycines) are major pests of soybeans (Glycines max) in Minnesota. Soybean aphids injure soybean plants by piercing the plants with tiny needle-like mouth parts and sucking out sap, which can reduce soybean yield. Due to their small size, aphids must occur in high numbers on soybean plants to result in yield loss. Such damaging populations occur yearly in Minnesota (but not necessarily the same regions every year), resulting in the need for an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) approach to successfully control this pest. Scouting Not all soybean fields are likely to have soybean aphid problems. Early aphid infestations in spring are often found in smaller fields near buckthorn, their primary overwintering plant, and migrate to soybean (See soybean aphid life-cycle in MN below). These infestations are often more abundant on tender and young leaves. Active scouting should be carried out from Mid-June through growth stage R6.5 (pods and leaves begin to yellow). As soybean progresses through reproductive growth stages, aphid populations move to leaves, stems and pods lower on the plants. The presence of lady beetles or ants are often indicative of soybean aphid populations. Sample 20-30 plants from throughout the entire field. Consider sampling at least 1x / week during active scouting period. Count both adults and nymphs (see picture on page 4). An alternative method to scouting is “speed scouting” or sequential sampling method. Speed scouting can be used to save time, however, this method provides less information and can slightly over-recommend treatment of fields. -

Aphid Transmission of Potyvirus: the Largest Plant-Infecting RNA Virus Genus

Supplementary Aphid Transmission of Potyvirus: The Largest Plant-Infecting RNA Virus Genus Kiran R. Gadhave 1,2,*,†, Saurabh Gautam 3,†, David A. Rasmussen 2 and Rajagopalbabu Srinivasan 3 1 Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA 2 Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27606, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Entomology, University of Georgia, 1109 Experiment Street, Griffin, GA 30223, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]. † Authors contributed equally. Received: 13 May 2020; Accepted: 15 July 2020; Published: date Abstract: Potyviruses are the largest group of plant infecting RNA viruses that cause significant losses in a wide range of crops across the globe. The majority of viruses in the genus Potyvirus are transmitted by aphids in a non-persistent, non-circulative manner and have been extensively studied vis-à-vis their structure, taxonomy, evolution, diagnosis, transmission and molecular interactions with hosts. This comprehensive review exclusively discusses potyviruses and their transmission by aphid vectors, specifically in the light of several virus, aphid and plant factors, and how their interplay influences potyviral binding in aphids, aphid behavior and fitness, host plant biochemistry, virus epidemics, and transmission bottlenecks. We present the heatmap of the global distribution of potyvirus species, variation in the potyviral coat protein gene, and top aphid vectors of potyviruses. Lastly, we examine how the fundamental understanding of these multi-partite interactions through multi-omics approaches is already contributing to, and can have future implications for, devising effective and sustainable management strategies against aphid- transmitted potyviruses to global agriculture. -

Insect Communities in Soybeans of Eastern South Dakota: the Effects

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska 2013 Insect communities in soybeans of eastern South Dakota: The effects of vegetation management and pesticides on soybean aphids, bean leaf beetles, and their natural enemies Jonathan G. Lundgren USDA-ARS, [email protected] Louis S. Hesler USDA-ARS Sharon A. Clay South Dakota State University, [email protected] Scott F. Fausti South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub Part of the Agriculture Commons Lundgren, Jonathan G.; Hesler, Louis S.; Clay, Sharon A.; and Fausti, Scott F., "Insect communities in soybeans of eastern South Dakota: The effects of vegetation management and pesticides on soybean aphids, bean leaf beetles, and their natural enemies" (2013). Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty. 1164. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub/1164 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Crop Protection 43 (2013) 104e118 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Crop Protection journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cropro Insect communities in soybeans of eastern South Dakota: The effects of vegetation management and pesticides on soybean aphids, bean leaf beetles, and their natural enemies Jonathan G. Lundgren a,*, Louis S. Hesler a, Sharon A. Clay b, Scott F.