Report Profundo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Next Jerusalem

The Next Introduction1 Jerusalem: Since the beginning of the Israeli-Palestinian Potential Futures conflict, the city of Jerusalem has been the subject of a number of transformations that of the Urban Fabric have radically changed its urban structure. Francesco Chiodelli Both the Israelis and the Palestinians have implemented different spatial measures in pursuit of their disparate political aims. However, it is the Israeli authorities who have played the key role in the process of the “political transformation” of the Holy City’s urban fabric, with the occupied territories of East Jerusalem, in particular, being the object of Israeli spatial action. Their aim has been the prevention of any possible attempt to re-divide the city.2 In fact, the military conquest in 1967 was not by itself sufficient to assure Israel that it had full and permanent The wall at Abu Dis. Source: Photo by Federica control of the “unified” city – actually, the Cozzio (2012) international community never recognized [ 50 ] The Next Jerusalem: Potential Futures of the Urban Fabric the 1967 Israeli annexation of the Palestinian territories, and the Palestinians never ceased claiming East Jerusalem as the capital of a future Palestinian state. So, since June 1967, after the overtly military phase of the conflict, Israeli authorities have implemented an “urban consolidation phase,” with the aim of making the military conquests irreversible precisely by modifying the urban space. Over the years, while there have been no substantial advances in terms of diplomatic agreements between the Israelis and the Palestinians about the status of Jerusalem, the spatial configuration of the city has changed constantly and quite unilaterally. -

Fact Sheet:Middle East and Africa ESG Screened Index Equity Sub

EMEA_INST Managed Pension Funds Limited Middle East and Africa ESG Screened Index Equity Sub-Fund Equities 30 June 2021 Fund Objective Performance ® The Sub-Fund aims to track the FTSE Developed Annualised Fund Benchmark Difference Middle East and Africa ex Controversies ex CW 1 Year (%) 23.30 23.28 0.01 Index, or its recognised replacement or equivalent. 3 Year (%) 4.75 4.84 -0.09 Investment Strategy 5 Year (%) 0.78 0.89 -0.11 The Sub-Fund primarily invests at all times in a Since Inception (%) 4.04 4.18 -0.14 sample of equities constituting the Index with such other securities as MPF shall deem it necessary Cumulative to capture the performance of the Index. Stock 3 Month (%) 11.54 11.51 0.04 index futures can be used for efficient portfolio 1 Year (%) 23.30 23.28 0.01 management. 3 Year (%) 14.95 15.24 -0.29 The following are excluded by the index provider from the index: Controversies (as defined by the ten 5 Year (%) 3.96 4.52 -0.56 principles of the UN Global Compact); Controversial Since Inception (%) 65.75 68.57 -2.81 weapons (including chemical & biological weapons, cluster munitions and anti-personnel landmines). Calendar 2021 (year to date) 9.74 9.71 0.03 Benchmark 2020 -1.28 -1.47 0.19 FTSE Developed Middle East and Africa ex 2019 10.82 11.07 -0.24 Controversies ex CW Index 2018 -0.47 -0.12 -0.35 Structure 2017 -10.77 -10.66 -0.12 Limited Company Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. -

Marah Al-Bakri (Website of 48Arab)

November 2, 2015 Initial Findings of the Profile of Palestinian Terrorists Who Carried Out Attacks in Israel in the Current Wave of Terrorism (Updated to October 25, 2015) The contagious effect of stabbing attacks: a notice posted to the Palestinian social networks, some of them affiliated with Hamas, reading "If you don't stand up for Jerusalem, who will?" It features recent postings written by terrorist operatives Muhannad Shafiq and Fadi Aloun, who were killed carrying out stabbing attacks in Jerusalem and became role models for terrorists who followed in their footsteps. Overview 1. The wave of Palestinian violence and terrorism currently plaguing Israel began during the most recent Jewish High Holidays. In retrospect, the ITIC has concluded it began with the stones thrown at the vehicle of Alexander Levlowitz near the Armon Hanatziv neighborhood of Jerusalem on September 14, 2015. Initially the wave of violence and terrorism focused on the Temple Mount and east Jerusalem and later spread throughout Jerusalem and to other sites inside Israel and various hotspots in Judea and Samaria (especially the region around Hebron). So far 12 1 Israelis and more than 70 Palestinians have been killed. 1 According to a spokesman of the Palestinian ministry of health so far 61 Palestinians have been killed (Voice of Palestine Radio, October 26, 2015). According to the written Palestinian media 71 Palestinians 179-15 2 2. The current wave of violence and terrorism is part of the overall "popular resistance" strategy adopted by the Palestinian Authority (PA) and Fatah at the Sixth Fatah Conference in August 2009.2 It is manifested by rising and falling levels of popular terrorism. -

Sur Bahir & Umm Tuba Town Profile

Sur Bahir & Umm Tuba Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Jerusalem Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Jerusalem Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, village, and town in the Jerusalem Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all villages in Jerusalem Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in the Jerusalem Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in the Jerusalem Governorate. -

The Economic Base of Israel's Colonial Settlements in the West Bank

Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute The Economic Base of Israel’s Colonial Settlements in the West Bank Nu’man Kanafani Ziad Ghaith 2012 The Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) Founded in Jerusalem in 1994 as an independent, non-profit institution to contribute to the policy-making process by conducting economic and social policy research. MAS is governed by a Board of Trustees consisting of prominent academics, businessmen and distinguished personalities from Palestine and the Arab Countries. Mission MAS is dedicated to producing sound and innovative policy research, relevant to economic and social development in Palestine, with the aim of assisting policy-makers and fostering public participation in the formulation of economic and social policies. Strategic Objectives Promoting knowledge-based policy formulation by conducting economic and social policy research in accordance with the expressed priorities and needs of decision-makers. Evaluating economic and social policies and their impact at different levels for correction and review of existing policies. Providing a forum for free, open and democratic public debate among all stakeholders on the socio-economic policy-making process. Disseminating up-to-date socio-economic information and research results. Providing technical support and expert advice to PNA bodies, the private sector, and NGOs to enhance their engagement and participation in policy formulation. Strengthening economic and social policy research capabilities and resources in Palestine. Board of Trustees Ghania Malhees (Chairman), Ghassan Khatib (Treasurer), Luay Shabaneh (Secretary), Mohammad Mustafa, Nabeel Kassis, Radwan Shaban, Raja Khalidi, Rami Hamdallah, Sabri Saidam, Samir Huleileh, Samir Abdullah (Director General). Copyright © 2012 Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) P.O. -

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: the Israeli Supreme Court

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: The Israeli Supreme Court rejects an appeal to prevent the demolition of the homes of four Palestinians from East Jerusalem who attacked Israelis in West Jerusalem in recent months. - Marabouts at Al-Aqsa Mosque confront a group of settlers touring Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 3: Palestinian MK Ahmad Tibi joins hundreds of Palestinians marching toward the Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Old City of Jerusalem to mark the Prophet Muhammad's birthday. Jan. 5: Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound while Israeli forces confiscate the IDs of Muslims trying to enter. - Around 50 Israeli forces along with 18 settlers tour Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 8: A Jewish Israeli man is stabbed and injured by an unknown assailant while walking near the Old City’s Damascus Gate. Jan. 9: Israeli police detain at least seven Palestinians in a series of raids in the Old City over the stabbing a day earlier. - Yedioth Ahronoth reports that the Israeli Intelligence (Shabak) frustrated an operation that was intended to blow the Dome of the Rock by an American immigrant. Jan. 11: Israeli police forces detain seven Palestinians from Silwan after a settler vehicle was torched in the area. Jan. 12: A Jerusalem magistrate court has ruled that Israeli settlers who occupied Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem may not make substantial changes to the properties. - Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound. Jan. 13: Israeli forces detained three 14-year old youth during a raid on Issawiyya and two women while leaving Al-Aqsa Mosque. Jan. 14: Jewish extremists morning punctured the tires of 11 vehicles in Beit Safafa. -

BULLETIN - JANUARY, 2012 Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol

The ERA BULLETIN - JANUARY, 2012 Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol. 55, No. 1 January, 2012 The Bulletin WELCOME TO OUR NEW READERS Published by the Electric Railroaders’ Association, For many of you, this is the first time that ing month. This month’s issue includes re- Incorporated, PO Box you are receiving The Bulletin. It is not a ports on transit systems across the nation. In 3323, New York, New new publication, but has been produced by its 53-year history there have been just three York 10163-3323. the New York Division of the Electric Rail- Editors: Henry T. Raudenbush (1958-9), Ar- roaders’ Association since May, 1958. Over thur Lonto (1960-81) and Bernie Linder For general inquiries, the years we have expanded the scope of (1981-present). The current staff also in- contact us at bulletin@ coverage from the metropolitan New York cludes News Editor Randy Glucksman, Con- erausa.org or by phone area to the nation and the world, and mem- tributing Editor Jeffrey Erlitz, and our Produc- at (212) 986-4482 (voice ber contributions are always welcomed in this tion Manager, David Ross, who puts the mail available). ERA’s website is effort. The first issue foretold the abandon- whole publication together. We hope that you www.erausa.org. ment of the Polo Grounds Shuttle the follow- will enjoy reading The Bulletin Editorial Staff: Editor-in-Chief: Bernard Linder THIRD AVENUE’S POOR FINANCIAL CONDITION LED News Editor: Randy Glucksman TO ITS CAR REBUILDING PROGRAM 75 YEARS AGO Contributing Editor: Jeffrey Erlitz This company, which was founded in 1853, the equipment was in excellent condition and was able to survive longer than any other was well-maintained. -

Public Companies Profiting from Illegal Israeli Settlements on Palestinian Land

Public Companies Profiting from Illegal Israeli Settlements on Palestinian Land Yellow highlighting denotes companies held by the United Methodist General Board of Pension and Health Benefits (GBPHB) as of 12/31/14 I. Public Companies Located in Illegal Settlements ACE AUTO DEPOT LTD. (TLV:ACDP) - owns hardware store in the illegal settlement of Ma'ale Adumim http://www.ace.co.il/default.asp?catid=%7BE79CAE46-40FB-4818-A7BF-FF1C01A96109%7D, http://www.machat.co.il/businesses.php, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/14/world/middleeast/14israel.html?_r=3&oref=slogin&oref=slogin&, http://investing.businessweek.com/research/stocks/snapshot/snapshot.asp?ticker=ACDP:IT ALON BLUE SQUARE ISRAEL LTD. (NYSE:BSI) - has facilities in the Barkan and Atarot Industrial Zones and operates supermarkets in many West Bank settlements www.whoprofits.org/company/blue- square-israel, http://www.haaretz.com/business/shefa-shuk-no-more-boycotted-chain-renamed-zol-b-shefa-1.378092, www.bsi.co.il/Common/FilesBinaryWrite.aspx?id=3140 AVGOL INDUSTRIES 1953 LTD. (TLV:AVGL) - has a major manufacturing plant in the Barkan Industrial Zone http://www.unitedmethodistdivestment.com/ReportCorporateResearchTripWestBank2010FinalVersion3.pdf (United Methodist eyewitness report), http://panjiva.com/Avgol-Ltd/1370180, http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/business/avgol- sees-bright-future-for-nonwoven-textiles-in-china-1.282397 AVIS BUDGET GROUP INC. (NASDAQ:CAR) - leases cars in the illegal settlements of Beitar Illit and Modi’in Illit http://rent.avis.co.il/en/pages/car_rental_israel_stations, http://www.carrentalisrael.com/car-rental- israel.asp?refr= BANK HAPOALIM LTD. (TLV:POLI) - has branches in settlements; provides financing for housing projects in illegal settlements, mortgages for settlers, and financing for the Jerusalem light rail project, which connects illegal settlements with Jerusalem http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/business/bank-hapoalim-to-lead-financing-for-jerusalem-light-rail-line-1.97706, http://www.whoprofits.org/company/bank-hapoalim BANK LEUMI LE-ISRAEL LTD. -

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Visitors Information

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Visitors Information Contact information Beer-Sheva | Marcus Family Campus Aya Bar-Hadas, Head, Visitors Unit, Dana Chokroon, Visits Coordinator, Office: 972-8-646-1750 Office: 972-8-642-8660 Fax: 972-8-647-2865 Fax: 972-8-647-2865 Cell: 972-52-579-3048 Cell: 972-52-879-5885 [email protected] [email protected] Efrat Borenshtain, Visits Coordinator, Hadas Moshe Bar-hat , Visits Coordinator, Office: 972-8-647-7671 Office: 972-8-646-1280 Fax: 972-8-647-2865 Fax: 972-8-647-2865 Cell: 972-50-202-9754 Cell: 972-50-686-3505 [email protected] [email protected] • When calling Israel from abroad dial: Exit code + 972 + x-xxx-xxxx o Example if call from a US number: 011-972-8-646-1750. • When calling from within Israel, replace the (972) with a zero. o Example: 08-646-1750. Directions To the Marcus Family Campus By train Take the train to Beer Sheva. Disembark the train at “Beer-Sheva North/University” station (this is the first of two stops in Beer-Sheva). Upon exiting the station, turn right onto the “Mexico Bridge” which leads to the Marcus Family Campus. (For on campus directions see map below). The train journey takes about 55 minutes (from Tel Aviv). For the train schedule, visit Israel Railways website: http://www.rail.co.il/EN/Pages/HomePage.aspx By car For directions, click here From Tel-Aviv (the journey should take about 1 hour 30 minutes, depending on traffic) If using WAZE to direct you to the Campus, enter the address as: Professor Khayim Khanani Street, Be'er Sheva. -

Great Tips for Travelling to Israel No One Ever Shared with You!

Great Tips for Travelling to Israel No One Ever Shared With You! By Ramael Ceo Hadur Travel and Tours Ltd www.smarttravelsuperfan.com Why Visit Israel? This e book will help you to learn why a visit to Jerusalem and the Holy Land of Israel is a Must Keep reading. A trip to Israel is more than exciting … It is life-changing! “Visit Israel –You’ll never be the same!” • Discover exclusive insider details you need to know before you decide to travel to Israel. • Amazing tips exposing all you ever need for easy touring of the Holy land. • Plus all the key attractions to look out for on your trip • Few Hebrew Phrases … and lots more www.smarttravelsuperfan.com Welcome! If you have ever had a strong desire to travel to Israel or have often wondered why anyone would ever want to travel to Israel then this guide is for you it will provide you with useful insights about all you need to know about the HOLY LAND of Israel. People’s single greatest expression when they return from a visit to Israel is, “I’ll never be the same.” Something about sailing on the Sea of Galilee, walking the streets of Jerusalem, and viewing the empty tomb creates an eternal change of heart and spirit. Wherever you go, you can sense God’s presence. When you visit Israel, God’s Word becomes clearer, your faith becomes deeper, and your passion for the Lord becomes stronger. We believe that, once you visit Israel, you’ll never be the same! Every detail you need to tour Israel is included in this guide. -

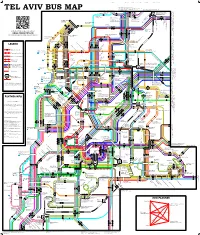

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

Excluded, for God's Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel

Excluded, For God’s Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel המרכז הרפורמי לדת ומדינה -לוגו ללא מספר. Third Annual Report – December 2013 Israel Religious Action Center Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism Excluded, For God’s Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel Third Annual Report – December 2013 Written by: Attorney Ruth Carmi, Attorney Ricky Shapira-Rosenberg Consultation: Attorney Einat Hurwitz, Attorney Orly Erez-Lahovsky English translation: Shaul Vardi Cover photo: Tomer Appelbaum, Haaretz, September 29, 2010 – © Haaretz Newspaper Ltd. © 2014 Israel Religious Action Center, Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism Israel Religious Action Center 13 King David St., P.O.B. 31936, Jerusalem 91319 Telephone: 02-6203323 | Fax: 03-6256260 www.irac.org | [email protected] Acknowledgement In loving memory of Dick England z"l, Sherry Levy-Reiner z"l, and Carole Chaiken z"l. May their memories be blessed. With special thanks to Loni Rush for her contribution to this report IRAC's work against gender segregation and the exclusion of women is made possible by the support of the following people and organizations: Kathryn Ames Foundation Claudia Bach Philip and Muriel Berman Foundation Bildstein Memorial Fund Jacob and Hilda Blaustein Foundation Inc. Donald and Carole Chaiken Foundation Isabel Dunst Naomi and Nehemiah Cohen Foundation Eugene J. Eder Charitable Foundation John and Noeleen Cohen Richard and Lois England Family Jay and Shoshana Dweck Foundation Foundation Lewis Eigen and Ramona Arnett Edith Everett Finchley Reform Synagogue, London Jim and Sue Klau Gold Family Foundation FJC- A Foundation of Philanthropic Funds Vicki and John Goldwyn Mark and Peachy Levy Robert Goodman & Jayne Lipman Joseph and Harvey Meyerhoff Family Richard and Lois Gunther Family Foundation Charitable Funds Richard and Barbara Harrison Yocheved Mintz (Dr.