Griffiths, David Barclay (1992) Confessions, Admissions and Declarations by Persons Accused of Crime Under Scots Law : a Historic and Comparative Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Taboo : why are real-life British serial killers rarely represented on film? EARNSHAW, Antony Robert Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Taboo: Why are Real-Life British Serial Killers Rarely Represented on Film? Antony Robert Earnshaw Sheffield Hallam University MA English by Research September 2017 1 Abstract This thesis assesses changing British attitudes to the dramatisation of crimes committed by domestic serial killers and highlights the dearth of films made in this country on this subject. It discusses the notion of taboos and, using empirical and historical research, illustrates how filmmakers’ attempts to initiate productions have been vetoed by social, cultural and political sensitivities. Comparisons are drawn between the prevalence of such product in the United States and its uncommonness in Britain, emphasising the issues around the importing of similar foreign material for exhibition on British cinema screens and the importance of geographic distance to notions of appropriateness. The influence of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) is evaluated. This includes a focus on how a central BBFC policy – the so- called 30-year rule of refusing to classify dramatisations of ‘recent’ cases of factual crime – was scrapped and replaced with a case-by-case consideration that allowed for the accommodation of a specific film championing a message of tolerance. -

Peter Manuel Beast of Birkenshaw

Peter Manuel Beast of Birkenshaw Information researched and summarized by: Jerry T. Atkins, Nicole Ballengee, & Kirsten Boyd Department of Psychology Radford University Radford, VA 24142-6946 Date Age Life Event 03/15/1927 0 Born in Misericordia Hospital, Manhattan, New York. Peter has an older brother, James who was born in 1925. 1932 5 Moved from U.S. to Motherwell, Scotland, due to father being terribly ill and mother wanting to be around family for help 1934 7 Sister Teresa is born. 1937 10 Attended Park St. Roman Catholic School in Motherwell, Scotland 1938 11 Family moved to Coventry, England 1939 12 First court appearance. Was bound for over 12 months for shoplifting, breaking and entering, and larceny 1942 15 Broke into his teacher’s house, attacked his wife by beating her with a candle stick holder, and then hid in the school’s nativity scene during the day. Charged with assault and breaking and entering. 06/24/1942 15 Went to Southport Juvenile Court on three charges of breaking into houses. 03/15/1943 16 Appeared in front of the Market Weighton Court and was committed to a borstal (youth prison) for two years. 1943 or 1944 (not Manuel was struck on the right side of his forehead by a piece of steel real clear) from an air raid bomb attack. He was knocked unconscious for few hours and was “blank minded” for a few days. 1944 Received an electric shock from his job that resulted in a loss of consciousness as well as burns – three e coworkers died in the incident. -

Readers Groups – Live Borders Book List

Readers Groups – Live Borders Book List The list of Readers Group titles below are available (on request) through your local Library and can be accessed for reading group purposes only. If you are currently part of a readers group affiliated with your local library, and there is a title your group would like to read and critique, feel free to request an appropriate quantity, within your local library. Please note – In most cases, we hold 12 copies of the listed titles. We welcome new stock suggestions, specifically for Readers Groups and this can also be done through your local library. If you are not yet part of a readers group, but you are interested in setting a new one up, please discuss further with library staff. Eyemouth Library on 01890 752767 or email: [email protected] Galashiels Library on 01896 664170 or email [email protected] Hawick Library on 01450 364640 or Email: [email protected] Peebles Library on Tel: 01721 726 333 or Email: [email protected] St Marys Mill (HQ) on 01750 726400 or Email: [email protected] 1 ALEXANDER, Dorothy - The Mauricewood Devils A meticulously researched, semi-fictionalised account the Mauricewood pit disaster near Edinburgh of 1889 related by seven year-old Martha and her step-mother Jess. Their accounts are given in the aftermath of the death of Martha's father and 62 others in the accident. With many of the miners families left destitute, the women of Mauricewood undertake a campaign for compensation and justice against the criminally negligent pit owners with key figures of the day, such as Keir Hardie and William Gladstone, playing roles in the cause celebre. -

DISCOVER NLS Answer to That Question Is ‘Plenty’! Our Nation’S Issue 24 WINTER 2013 Contribution to the Rest of Mankind Is Substantial CONTACT US and Diverse

LAW AND ORDER ON FILM Documenting the fight against crime The magazine of the National Library of Scotland www.nls.uk | Issue 24 Winter 2013 f t h Wha’s Like Us An A-Z of what Scotland has b given the world s j x p Best-selling Scots of Launching the NLS Field Marshal the 19th century Gaelic catalogue Haig’s war diary WELCOME Celebrating Scotland’s global contribution What has Scotland given to the world? The quick DISCOVER NLS answer to that question is ‘plenty’! Our nation’s ISSUE 24 WINTER 2013 contribution to the rest of mankind is substantial CONTACT US and diverse. We welcome all comments, For a small country we have more than pulled our questions, submissions and subscription enquiries. weight, contributing significantly to science, economics, Please write to us at the politics, the arts, design, food and philosophy. And there National Library of Scotland address below or email are countless other examples. Our latest exhibition, [email protected] Wha’s Like Us? A Nation of Dreams and Ideas, which is covered in detail in these pages, seeks to construct FOR NLS EDITOR-IN-CHIEF an alphabetical examination of Scotland’s role in Alexandra Miller shaping the world. It’s a sometimes surprising collection EDITORIAL ADVISER Willis Pickard of exhibits and ideas, ranging from cloning to canals, from gold to Grand Theft Auto. Diversity is also at the heart of Willis Pickard’s special CONTRIBUTORS Bryan Christie, Martin article in this issue. Willis is a valued member of the Conaghan, Jackie Cromarty, Library’s Board, but will soon be standing down from that Gavin Francis, Alec Mackenzie, Nicola Marr, Alison Metcalfe, position. -

Why Are Real-Life British Serial Killers Rarely Represented on Film?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive Taboo : why are real-life British serial killers rarely represented on film? EARNSHAW, Antony Robert Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version EARNSHAW, Antony Robert (2017). Taboo : why are real-life British serial killers rarely represented on film? Masters, Sheffield Hallam University. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Taboo: Why are Real-Life British Serial Killers Rarely Represented on Film? Antony Robert Earnshaw Sheffield Hallam University MA English by Research September 2017 1 Abstract This thesis assesses changing British attitudes to the dramatisation of crimes committed by domestic serial killers and highlights the dearth of films made in this country on this subject. It discusses the notion of taboos and, using empirical and historical research, illustrates how filmmakers’ attempts to initiate productions have been vetoed by social, cultural and political sensitivities. Comparisons are drawn between the prevalence of such product in the United States and its uncommonness in Britain, emphasising the issues around the importing of similar foreign material for exhibition on British cinema screens and the importance of geographic distance to notions of appropriateness. The influence of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) is evaluated. This includes a focus on how a central BBFC policy – the so- called 30-year rule of refusing to classify dramatisations of ‘recent’ cases of factual crime – was scrapped and replaced with a case-by-case consideration that allowed for the accommodation of a specific film championing a message of tolerance. -

The Serial Killer Files

CONTENTS Title Page Dedication Half Title Page Introduction ONE: WHAT IT MEANS Origin of the Term Definitions Categories of Carnage: Serial/Mass/Spree Psychopath vs. Psychotic Psychopaths: The Mask of Sanity “Moral Insanity” Psychotics: The Living Nightmare Beyond Madness TWO: WHO THEY ARE Ten Traits of Serial Killers Warning Signs How Smart Are Serial Killers? Male and Female Angels of Death Black Widows Deadlier Than the Male Black and White Young and Old Straight and Gay Bloodthirsty “Bi”s Partners in Crimes Folie à Deux Killer Couples The Family That Slays Together Married with Children Bluebeards Work and Play Uncivil Servants Killer Cops Medical Monsters Nicknames Serial Killers International THREE: A HISTORY OF SERIAL MURDER Serial Murder: Old as Sin Grim Fairy Tales Serial Slaughter Through the Ages FOUR: GALLERY OF EVIL—TEN AMERICAN MONSTERS Lydia Sherman Belle Gunness H. H. Holmes Albert Fish Earle Leonard Nelson Edward Gein Harvey Murray Glatman John Wayne Gacy Gary Heidnik Jeffrey Dahmer FIVE: SEX AND THE SERIAL KILLER Perversions Sadism The Man Who Invented Sadism Science Looks at Sadism Wilhelm Stekel de River and Reinhardt Disciples of De Sade Dominance Fetishism Transvestism Vampirism Cannibalism Necrophilia Pedophilia Gerontophilia The World’s Worst Pervert SIX: WHY THEY KILL Atavism Brain Damage Child Abuse Mother Hate Bad Seed Mean Genes Adoption Fantasy Bad Books, Malignant Movies, Vile Videos Pornography Profit Celebrity Copycats The Devil Made Me Do It SEVEN: EVIL IN ACTION Triggers Hunting Grounds Prey Targets of -

S.A.S.D. Bulletin 03

The Scottish Journal of Criminal Justice Studies The Journal of the Scottish Association for the Study of Delinquency Editor Jason Ditton Scottish Centre for Criminology, First Floor, 19 Kelvinside Gardens East, Glasgow, G20 6BE Tel: 0141-946 4325 Email: [email protected] Assistant Editor Michele Burman Sociology Department, Glasgow University, Adam Smith Building, Glasgow G12 8RT Tel: 0141-330 6983 Email: [email protected] Volume 9, July, 2003. 1 2 EDITORIAL This is the ninth volume of the Scottish Journal of Criminal Justice Studies. In this issue, our branch generated article was initially aired at a meeting of the Edinburgh Branch in March, 2003. For the first time in this volume, we reprint the content of posters that were on display at the Annual Conference. In the final section, we reprint a note on the Objects and Membership of SASD, list the Associations’ Office Bearers and Branch Secretaries and add a note on how to start a new Branch. In future volumes of the Journal, I hope to continue to publish as articles those papers presented at Branch Meetings or Day Conferences that Branch Secretaries think are worth offering to a wider audience. Original articles will also be considered for publication. There is no copy deadline. Branch Secretaries are invited to send suitable articles to me (in Word 2000 – or earlier versions - or in .rtf format) by attaching them to an email to me. Jason Ditton 3 4 CONTENTS Page Editorial ......................................................................................................................3 Keynote Article By Richard Simpson, MSP, Deputy Minister for Justice ..........................................7 Conference Report “Sentencing” SASD’s 33rd Annual Conference. -

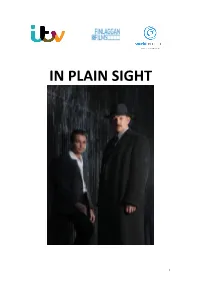

In Plain Sight

IN PLAIN SIGHT 1 Contents Press Release ....................................................................................................... Pages 3-4 Introduction by writer Nick Stevens ...................................................................... Page 5-6 Interview with Douglas Henshall (William Muncie) .......................................... Pages 7-10 Interview with Martin Compston (Peter Manuel) ........................................... Pages 11-14 Episode one synopsis ........................................................................................ Page 15-16 Cast and Production Credits ................................................................................... Page 21 2 IN PLAIN SIGHT In Plain Sight is a new three-part mini-series based on the true story of Lanarkshire detective William Muncie’s quest to bring to justice notorious Scottish killer Peter Manuel. Douglas Henshall (Collision, Shetland) takes the role of William Muncie whilst Peter Manuel is played by Martin Compston (Line of Duty). Produced by critically acclaimed, award winning producers World Productions (Line of Duty, Code of a Killer) and Finlaggan Films. After extensively researching the story, this is Nick Stevens’ TV writing debut. The mini-series is directed by John Strickland, who helmed the recent Line of Duty finale. Muncie first arrested Manuel in 1946 for housebreaking, but also successfully convicted him for a string of sexual assaults. Manuel vowed revenge. 3 Released from prison in 1955, Manuel embarked on a two-year -

Standing of Civil Society and Civil Liberties As Well As Duties, and to Reconstruct an Economy That Is Not Simply Dominated by Free Market Forces

Contents Editorial 3 New Scottish Poetry 5 (New) Media in / on Scotland 5 Education Scotland 7 Scottish Award Winners 9 Recent Publications 11 Book Review 48 Conference Report 50 Conference Announcements 53 3 Editorial Dear Subscriber / Reader, This issue of the Scottish Studies Newsletter will take up and continue what Professor Horst Drescher began in 1981, when he set up the 'Scottish Studies Centre' in the English Depart- ment of the Germersheim faculty of the Johannes Gutenberg-University of Mainz and started the Newsletter in 1984. There was some interruption in the output of issues after nos. 36 & 37 in 2008, mainly due to illness, but the new team of editors is now in a position to continue his excellent work with him as the main spiritus rector in their midst. There will be two issues each year, one in April, the other in October, passing on information on important developments in all areas of Scottish Studies we learn about. We, therefore, depend not only on our own work, but to a great extent, indeed even more, on what we get to know about from people in Scottish as well as international institutions, from practitioners, theorists, scholars, creative writers, artists, publishers, politicians, and everybody working in, on, or for Scotland. It is in this context that we strongly invite your support for our endeavour by sending us comments, contributions, information, publications, and everything else that will keep the Newsletter alive and intriguing for readers. The biggest section in this issue is the one dealing with new publications, a section we will probably have in all subsequent issues, too. -

The Beast of Birkenshaw: Life of Serial Killer Peter Manuel by Jack Smith

The Beast Of Birkenshaw: Life Of Serial Killer Peter Manuel By Jack Smith If you are looking for the ebook by Jack Smith The Beast of Birkenshaw: Life of Serial Killer Peter Manuel in pdf form, in that case you come on to right website. We furnish the complete option of this book in txt, PDF, doc, DjVu, ePub forms. You can read by Jack Smith online The Beast of Birkenshaw: Life of Serial Killer Peter Manuel either downloading. In addition, on our website you can reading manuals and different art eBooks online, or load their as well. We want to invite your regard that our website not store the eBook itself, but we grant ref to the site whereat you can load or read online. If need to download by Jack Smith pdf The Beast of Birkenshaw: Life of Serial Killer Peter Manuel, then you have come on to right site. We have The Beast of Birkenshaw: Life of Serial Killer Peter Manuel txt, doc, ePub, DjVu, PDF formats. We will be pleased if you return more. The beast of birkenshaw: life of serial killer peter The Beast of Birkenshaw: Life of Serial Killer Peter Manuel eBook: Jack Smith: Amazon.co.uk: Kindle Store [PDF] Oh Myyy!: There Goes The Internet.pdf Serial killer peter manuel and the incredible tale of his Serial killer Peter Manuel and the incredible tale of his naked sister and George Galloway. Manuel was called the Beast of Birkenshaw for the depravity of his [PDF] The Night Of The Swarm.pdf The beast of birkenshaw: life of serial killer peter manuel The Beast of Birkenshaw has 72 ratings and 5 reviews. -

Records Relating to the Trial and Execution of Peter Thomas Anthony Manuel

National Archives of Scotland Records Relating to the Trial and Execution of Peter Thomas Anthony Manuel Recent media interest has centred on the convicted murderer Peter Manuel who was executed in July 1958. Manuel was hanged in Barlinnie prison in Glasgow almost 50 years ago, following trial and conviction for the murder of seven people in the West of Scotland. He remains one of Scotland’s most notorious serial killers. The National Archives of Scotland (NAS) holds many records about the Manuel case, in particular the investigation by the police and his prosecution by the Crown Office, his trial at the High Court of Justiciary in Glasgow in May 1958, during which he dismissed his counsel and conducted his own defence, and Manuel’s prison files and execution. Most of these records have been open to the public for many years, though a small number remain exempt or restricted, and are therefore closed to public inspection. To facilitate further research on the Manuel case, we have published details about the records we hold and their current access status under either the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 or the Data Protection Act 1998. 1. Crown Office Records 2. High Court of Justiciary Records 3. Scottish Government Files National Archives of Scotland – Records Relating to the Trial and Execution of Peter Thomas Anthony Manuel 1 June 2008 http://www.nas.gov.uk National Archives of Scotland Records Relating to the Trial and Execution of Peter Thomas Anthony Manuel Part 1: Crown Office Records Crown Office files are subject to both the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 and the Data Protection Act 1998. -

Candidates Scotland

Page | 1 LIBERAL/LIBERAL DEMOCRAT CANDIDATES IN SCOTLAND 1945-2015 INCLUDING SDP CANDIDATES in the GENERAL ELECTIONS of 1983 and 1987 PREFACE The compilation of this Index has presented no special difficulty compared with some Regions. Few candidates listed have contested parliamentary elections outside Scotland, of whom only one individual stood in more than one region. This has made the process of cross-checking straightforward. Changes of names of constituencies over the years have caused some confusion. A helpful factor has been that many candidates, including long standing MPs, have presented themselves for election on multiple occasions. Scotland has been traditionally one of the party’s strongest regions though there was a bleak period, 1945-50, when there were no Scottish Liberal MPs. There were two for the brief interval 1950-51 but from 1951-64, Jo Grimond remained the sole Scottish Liberal MP at Westminster. The position improved considerably in 1964 and until the catastrophe of May 2015 there was always a strong Scottish contingent on the Liberal benches at Westminster, including a succession of four party leaders. Liberal/Liberal Democrat strength in Scotland has always centred upon the Highlands, Islands and rural areas. It was only in the last two decades before 2015 that seats were won in urban areas. Many constituencies in Glasgow and the Lowlands were left uncontested, in some instances from the 1920s. They remained neglected until the mid-1970s when candidates were at last selected for these ‘derelict’ constituencies. Recognition is made in some entries to ‘pioneer’ candidates who were the first to contest such constituencies.