Bodoland Movement: a Study Topu Choudhury Asst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6.Hum-RECEPTION and TRANSLATION of INDIAN

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN(E): 2321-8878; ISSN(P): 2347-4564 Vol. 3, Issue 12, Dec 2015, 53-58 © Impact Journals RECEPTION AND TRANSLATION OF INDIAN LITERATURE INTO BORO AND ITS IMPACT IN THE BORO SOCIETY PHUKAN CH. BASUMATARY Associate Professor, Department of Bodo, Bodoland University, Kokrajhar, Assam, India ABSTRACT Reception is an enthusiastic state of mind which results a positive context for diffusing cultural elements and features; even it happens knowingly or unknowingly due to mutual contact in multicultural context. It is worth to mention that the process of translation of literary works or literary genres done from one language to other has a wide range of impact in transmission of culture and its value. On the one hand it helps to bridge mutual intelligibility among the linguistic communities; and furthermore in building social harmony. Keeping in view towards the sociological importance and academic value translation is now-a-day becoming major discipline in the study of comparative literature as well as cultural and literary relations. From this perspective translation is not only a means of transference of text or knowledge from one language to other; but an effective tool for creating a situation of discourse among the cultural surroundings. In this brief discussion basically three major issues have been taken into account. These are (i) situation and reason of welcoming Indian literature and (ii) the process of translation of Indian literature into Boro and (iii) its impact in the society in adaption of translation works. KEYWORDS: Reception, Translation, Transmission of Culture, Discourse, Social Harmony, Impact INTRODUCTION The Boro language is now-a-day a scheduled language recognized by the Government of India in 2003. -

THE DYNAMICS of the DEMOBILIZATION of the PROTEST CAMPAIGN in ASSAM Tijen Demirel-Pegg Indiana University-Purdue University Indi

THE DYNAMICS OF THE DEMOBILIZATION OF THE PROTEST CAMPAIGN IN ASSAM Tijen Demirel-Pegg Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Abstract: This study highlights the role that critical events play in the demobilization of protest campaigns. Social movement scholars suggest that protest campaigns demobilize as a consequence of polarization within the campaign or the cooptation of the campaign leaders. I offer critical events as an alternative causal mechanism and argue that protest campaigns in ethnically divided societies are particularly combustible as they have the potential to trigger unintended or unorchestrated communal violence. When such violence occurs, elite strategies change, mass support declines and the campaign demobilizes. An empirical investigation of the dynamics of the demobilization phase of the anti-foreigner protest campaign in Assam, India between 1979 and 1985 confirms this argument. A single group analysis is conducted to compare the dynamics of the campaign before and after the communal violence by using time series event data collected from The Indian Express, a national newspaper. The study has wider implications for the literature on collective action as it illuminates the dynamic and complex nature of protest campaigns. International Interactions This is the author's manuscript of the article to be published in final edited form at: Demirel-Pegg, Tijen (2016), “The Dynamics of the Demobilization of the Protest Campaign in Assam,” International Interactions. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03050629.2016.1128430 Introduction The year 2014 was marked by intense protests against the police after the killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson and Eric Garner in New York and the subsequent failure to indict the police officers that killed them. -

Tribal Land Alienation and Ethnic Conflict: Efficacy of Laws and Policies in BTAD Area

Tribal Land Alienation and Ethnic Conflict: Efficacy of Laws and Policies in BTAD Area By Nirmalya Banerjee * Bimal Musahary was standing in front of his charred hut, staring at the only piece of his belonging that he could still recognize; a half-burnt fan hanging from the ceiling. Villagers of Puniyagaon had all fled to the relief camp at Mudaibori, Bimal himself was also taking shelter in the safety of the camp at night. It was after the riots that had rocked the Udalguri and Darrang districts of Assam in 2008. Inmates of the rather large relief camp at Mudaibori were a mixed bag; there were Bodos, Garos, Asomiyas as well as Bengali Hindus. This camp was in Udalguri district, while the Mulsims evicted by the riots were in different relief camps, near Dalgaon in Darrang district. About a month after the riots had ended, one afternoon a few farmers were harvesting standing crop on a plot of land by the side of national highway 52, not far from the Rowta crossing, an area hit by violence. A group of people stood at the edge of the plot, watching the men working on the field. Men of the group were members of a committee that had been formed in the village to ensure peaceful harvesting. Such committees comprised members of both Bodo and Muslim communities. They had been formed to oversee the process of harvesting, so that people from the two communities do not clash over harvesting rights. Many of the ethnic clashes that have rocked the north bank of Assam frequently, can be traced back to fight over land; displacing large numbers of people. -

1.How Many People Died in the Earthquake in Lisbon, Portugal? A

www.sarkariresults.io 1.How many people died in the earthquake in Lisbon, Portugal? A. 40,000 B. 100,000 C. 50,000 D. 500,000 2. When was Congress of Vienna opened? A. 1814 B. 1817 C. 1805 D. 1810 3. Which country was defeated in the Napoleonic Wars? A. Germany B. Italy C. Belgium D. France 4. When was the Vaccine for diphtheria founded? A. 1928 B. 1840 C. 1894 D. 1968 5. When did scientists detect evidence of light from the universe’s first stars? A. 2012 B. 2017 C. 1896 D. 1926 6. India will export excess ___________? A. urad dal B. moong dal C. wheat D. rice 7. BJP will kick off it’s 75-day ‘Parivartan Yatra‘ in? A. Karnataka B. Himachal Pradesh C. Gujrat D. Punjab 8. Which Indian Footwear company opened it’s IPO for public subscription? A. Paragon B. Lancer C. Khadim’s D. Bata Note: The Information Provided here is only for reference. It May vary the Original. www.sarkariresults.io 9. Who was appointed as the Consul General of Korea? A. Narayan Murthy B. Suresh Chukkapalli C. Aziz Premji D. Prashanth Iyer 10. Vikas Seth was appointed as the CEO of? A. LIC of India B. Birla Sun Life Insurance C. Bharathi AXA Life Insurance D. HDFC 11. Who is the Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh? A. Babulal gaur B. Shivraj Singh Chouhan C. Digvijaya Singh D. Uma Bharati 12. Who is the Railway Minister of India? A. Piyush Goyal B. Dr. Harshvardhan C. Suresh Prabhu D. Ananth Kumar Hegade 13. -

Jou: the Traditional Drink of the Boro Tribe of Assam and North East India

Journal of Scientific and Innovative Research 2014; 3 (2): 239-243 Available online at: www.jsirJournal.com Research Article Jou: the traditional drink of the Boro tribe of Assam ISSN 2320-4818 and North East India JSIR 2014; 3(2): 239-243 © 2014, All rights reserved Received: 14-12-2013 Tarun Kumar Basumatary*, Reena Terangpi, Chandan Brahma, Padmoraj Roy, Accepted: 15-04-2014 Hankhray Boro, Hwiyang Narzary, Rista Daimary, Subhash Medhi, Birendra Kumar Brahma, Sanjib Brahma, Anuck Islary, Shyam Sundar Swargiary, Sandeep Das, Ramie H. Begum, Sujoy Bose Tarun Kumar Basumatary, Reena Terangpi, Ramie H. Begum Abstract Department of Life Science & Bioinformatics, Assam University, Jou is an integral part of the socio-cultural life of the Boros. The Boro has an old age tradition Diphu Campus, Diphu, Karbi Anglong, Assam 782460, India of preparing Jou from fermented cooked rice (jumai) with locally prepared yeast cake called Amao. Jou is traditionally used in marriage, worship and in all social occasions and it is of three Chandan Brahma, Padmoraj kinds Jou- bidwi, finai and gwran (distilled alcohol from jumai). Amao is traditionally prepared Roy, Hankhray Boro Department of Biotechnology, from seven plants species- Oryza sativa L., Scoparia dulcis L., Musa paradisiaca, Artocarpus Bodoland University, Kokrajhar, heterophyllus Lamk., Ananas comosus (L). Merr., Clerodendron infortunetum L., Plumbago Assam 783370, India zeylancia L. Boro, an ethnic tribe in Kokrajhar district of Assam state, Northeast India is the Hwiyang Narzary, Rista material of the present study where elderly men and women were exclusively selected for the Daimary, Birendra Kumar interview. The research included participatory approach of unstructured and semi-structured Brahma interviews and group discussions. -

Adivasis of India ASIS of INDIA the ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR an MRG INTERNA

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R T The Adivasis of India ASIS OF INDIA THE ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR AN MRG INTERNA BY RATNAKER BHENGRA, C.R. BIJOY and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI THE ADIVASIS OF INDIA © Minority Rights Group 1998. Acknowledgements All rights reserved. Minority Rights Group International gratefully acknowl- Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- edges the support of the Danish Ministry of Foreign commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- Affairs (Danida), Hivos, the Irish Foreign Ministry (Irish mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. Aid) and of all the organizations and individuals who gave For further information please contact MRG. financial and other assistance for this Report. A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 897693 32 X This Report has been commissioned and is published by ISSN 0305 6252 MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the Published January 1999 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the Typeset by Texture. authors do not necessarily represent, in every detail and Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. in all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. THE AUTHORS RATNAKER BHENGRA M. Phil. is an advocate and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI has been an active member consultant engaged in indigenous struggles, particularly of the Naga Peoples’ Movement for Human Rights in Jharkhand. He is convenor of the Jharkhandis Organi- (NPMHR). She has worked on indigenous peoples’ issues sation for Human Rights (JOHAR), Ranchi unit and co- within The Other Media (an organization of grassroots- founder member of the Delhi Domestic Working based mass movements, academics and media of India), Women Forum. -

“Crisis of Political Leadership in Assam”

“Crisis of Political Leadership in Assam” A Dissertation submitted to Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth for the Degree of Master of Philosophy Degree in Political Science Submitted By Ms.Yesminara Hussain Under the guidance of Dr. Manik Sonawane Head, Dept. of Political Science. Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. March - 2015 i ACKNOWLEDGMENT I take this opportunity, to express my sincere gratitude and thanks to all those who have helped me in completing my dissertation work for M.Phil. Degree. Words seem to be insufficient to express my deep gratitude to my teacher, supervisor, philosopher, and mentor and guide Dr. Manik Sonawane, Head- Department of Political Science, Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth Pune for his patient guidance, co-operation and invaluable suggestions during this work. He was kind to extend all possible help to me. He has been a limitless source of inspiration to me in my endeavor to explore this area of study. I am extremely grateful to him for all the toil and trouble he had taken for me. I record my deep sense of gratitude to Dr. Karlekar, Dean, Moral and Social Sciences, and Dr. Manik Sonawane, Head, Department of Political Science, Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. I owe deep sense of gratitude to my father Mr.Mobarak Hussain and mother AleyaKhatun and friends for their encouragement right from the commencement to the completion of my work. Date: 16th Feb.2015 YesminaraHussian Place: Pune Researcher ii DECLARATION I, Yesminara Hussain, hereby declare that the references and literature that are used in my dissertation entitled, “Crisis of Political Leadership in Assam”are from original sources and are acknowledged at appropriate places in the dissertation. -

Autonomy Movement and Durable Solution: a Historical Interpretation of Bodo Movement

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 8, ISSUE 10, OCTOBER 2019 ISSN 2277-8616 Autonomy Movement And Durable Solution: A Historical Interpretation Of Bodo Movement Shikha Moni Borah Abstract-Mobilization and movement to reclaim lost identity and space as well as to carve out new one is a universal phenomenon. In North Eastern part of India ethnicity and identity are the root causes behind such mobilization. In western part of Assam, the Bodos have been fighting for the cause of a separate Bodoland. A historical understanding of the movement have brought into light different phases of the same: from moderate to militant phases out of its interplay with different factors. The response from the state is visible in different forms; sometimes through the means of suppression while on other times through political and constitutional solutions as evident in the creation of Bodoland Territorial Council. In understanding the same the paper seeks to understand the particular historical juncture at which different autonomy arrangement has been innovated and at the same time durability of such arrangement is critically analyzed. Index Terms: Bodo, autonomy movement, ethnicity, Assam movement, Bodoland Territorial Council, sixth schedule, peace accord.. ———————————————————— 1. INTRODUCTION polity, land alienation, discriminatory clauses of Assam The recent urgency to relook the Bodoland region emerged accord and social and economic backwardness fuelled by in the context of violent conflicts of 2014 between the illegal migration (Sanjib, 1999). It is against such injustices Bodos and non- Bodos over the prospect of winning the Lok that the frustrated educated Bodo elites and intellectuals Sabha election from the Kokrajhar constituency by a non- have been putting forward their demand for more autonomy Bodo. -

Monthly Multidisciplinary Research Journal

Vol 6 Issue 4 Jan 2017 ISSN No : 2249-894X ORIGINAL ARTICLE Monthly Multidisciplinary Research Journal Review Of Research Journal Chief Editors Ashok Yakkaldevi Ecaterina Patrascu A R Burla College, India Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Kamani Perera Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Lanka Welcome to Review Of Research RNI MAHMUL/2011/38595 ISSN No.2249-894X Review Of Research Journal is a multidisciplinary research journal, published monthly in English, Hindi & Marathi Language. All research papers submitted to the journal will be double - blind peer reviewed referred by members of the editorial Board readers will include investigator in universities, research institutes government and industry with research interest in the general subjects. Regional Editor Manichander Thammishetty Ph.d Research Scholar, Faculty of Education IASE, Osmania University, Hyderabad. Advisory Board Kamani Perera Delia Serbescu Mabel Miao Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Spiru Haret University, Bucharest, Romania Center for China and Globalization, China Lanka Xiaohua Yang Ruth Wolf Ecaterina Patrascu University of San Francisco, San Francisco University Walla, Israel Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Karina Xavier Jie Hao Fabricio Moraes de AlmeidaFederal Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), University of Sydney, Australia University of Rondonia, Brazil USA Pei-Shan Kao Andrea Anna Maria Constantinovici May Hongmei Gao University of Essex, United Kingdom AL. I. Cuza University, Romania Kennesaw State University, USA Romona Mihaila Marc Fetscherin Loredana Bosca Spiru Haret University, Romania Rollins College, USA Spiru Haret University, Romania Liu Chen Beijing Foreign Studies University, China Ilie Pintea Spiru Haret University, Romania Mahdi Moharrampour Nimita Khanna Govind P. Shinde Islamic Azad University buinzahra Director, Isara Institute of Management, New Bharati Vidyapeeth School of Distance Branch, Qazvin, Iran Delhi Education Center, Navi Mumbai Titus Pop Salve R. -

April 4, 2020 | Vol LV No 14

APRIL 4, 2020 Vol LV No 14 ` 110 A SAMEEKSHA TRUST PUBLICATION www.epw.in EDITORIALS Fighting COVID-19 India’s Public Health System on Trial? The long-term effects of the COVID-19 outbreak will not Survival and Mobility in the Midst only require political will and decisive actions of the of a Pandemic government for economic stimulus, but also the fostering FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK of social solidarity for community resilience. pages 10, 16 COVID-19 and the Question of Taming Social Anxiety Goal of Higher Education COMMENTARY Is the massification of higher education in India aimed Impact of COVID-19 and What Needs at providing knowledge for its sake, or to facilitate the to Be Done training of minds in a neo-liberal nationalist agenda of Fighting Fires: Migrant Workers in Mumbai economic development? page 21 Reducing the Spread of COVID-19 Politics of Scheduled Tribe Status in Assam Dynamics of Folk Music The Idea of a University in India An exploration of Assam’s Goalpariya folk form reveals BOOK REVIEWS that the dynamism in folk music is rendered through its A Shot of Justice: Priority-Setting for linkages with the themes of identity assertion, tradition, Addressing Child Mortality authenticity, and contexts of appropriation. page 30 A Multilingual Nation: Translation and Language Dynamic in India PERSPECTIVES Devolution vs Reforms Gender, Space and Identity in Goalpariya When economic reforms triumph over democratic Folk Music of Assam decentralisation, as evidenced in Gujarat, there arises a SPECIAL ARTICLES need for a minimum constitutionally guaranteed The Troubled Ascent of a Marine Ring Seine devolution to local governments to safeguard against Fishery in Tamil Nadu the vicissitudes of state-level politics. -

Customary Belief and Faiths of the Boros in Bwisagu Festival

International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies Volume 3, Issue 4, April 2016, PP 30-33 ISSN 2394-6288 (Print) & ISSN 2394-6296 (Online) Customary Belief and Faiths of the Boros in Bwisagu Festival Bipul Chandra Basumatary Assistant Professor, Commerce College, Kokrajhar P.O. & Dist.-Kokrajhar, BTAD, Assam. Research Scholar Bodoland University, Kokrajhar, BTC, Assam. India ABSTRACT The Boros are the largest tribal people of Assam. They are known in different names in different places. They have some define festivals that identify themselves as a rich community. All the racesand communities of the world have some belief and faiths relating with the festivals. The Boro people have also some customary belief and faiths. Some of their belief and faiths has become diminishing or become futile in present scientific age. Though their belief and faiths have no scientific proof yet it has tremendous significance in their society in ancient as well as modern age. Attempt has been made to focus on those faiths, better understanding and its significance in the Boro society in conveyance to Bwisagu festival for their neighbours. Keywords: Boros, Festival, Belief and Faiths, its significances. INTRODUCTION The habit of belief and faith linger in every race and community of people. In olden times, from beginning of the social life; the people depended on the mighty nature. They learn various lessons from nature in their life. Thus they acquired various experiences living in the nature. As such certain belief and faiths have come into existences with the experiences gathers from living and those are use as advice for the generation to generations. -

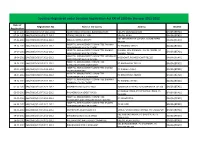

Ngos Registered in the State of Assam 2011-12.Pdf

Societies Registered under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the year 2011-2012 Date of Registration No. Name of the Society Address District Registration 06-04-2011 BAK/260/D/165 OF 2011-2012 GAON UNNAYAN SAMITI, BARSIMALUGURI VILL/PO BARSIMALUGURI BAKSA (BTAD) 07-04-2011 BAK/260/D/01 OF 2011-2012 STRING'S MUSICAL CLUB VILL/PO JALAH BAKSA (BTAD) VILL HAZUWA NEW COLONY, PO KAKLABARI- 07-04-2011 BAK/260/D/02 OF 2011-2012 MILIJULI MAHILA SAMITY BAKSA (BTAD) 781330 HOSPITAL MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE THAMNA 19-04-2011 BAK/260/D/03 OF 2011-2012 PO THAMNA-781377 BAKSA (BTAD) MINI PRIMARY HEALTH CENTRE HOSPITAL MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE BARBARI DHANBIL MINI PRIMARY HEALTH CENTRE, PO 19-04-2011 BAK/260/D/04 OF 2011-2012 BAKSA (BTAD) MINI PRIMARY HEALTH CENTRE DHANBIL-781343 HOSPITAL MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE MEDAGHAT 19-04-2011 BAK/260/D/05 OF 2011-2012 MEDAGHAT, PO MEDAGHAT-781355 BAKSA (BTAD) MINI PRIMARY HEALTH CENTRE HOSPITAL MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE 19-04-2011 BAK/260/D/06 OF 2011-2012 PO BARIMAKHA-781333 BAKSA (BTAD) BARIMAKHA STATE DISPENSARY HOSPITAL MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE DIGHELI 19-04-2011 BAK/260/D/07 OF 2011-2012 PO DIGHELI-781371 BAKSA (BTAD) STATE DISPENSARY HOSPITAL MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE 19-04-2011 BAK/260/D/08 OF 2011-2012 PO DEBACHARA-781333 BAKSA (BTAD) DEBACHARA STATE DISPENSARY HOSPITAL MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE BARAMA 19-04-2011 BAK/260/D/09 OF 2011-2012 PO BARAMA-781346 BAKSA (BTAD) PRIMARY HEALTH CENTRE 02-05-2011 BAK/260/D/10 OF 2011-2012 KARAMPATTAN SOCIETY NGO KUMARIKATA BAZAR, PO KUMARIKATA-781360 BAKSA (BTAD) HO BANGALIPARA, PO NIZ