Assiniboine Park Pavilion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assiniboine Park Governance Study

Assiniboine Park Governance Study February 2006 (Revised) Prepared by The Acumen Group with HILDERMAN THOMAS FRANK CRAM Landscape Architecture • Planning 500-115 Bannatyne Avenue East, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3B 0R3 Telephone 204•944•9907 Facsimile 204•957•1467 Table of Contents Overview 1 Nature of the Assignment 5 Assiniboine Park in Retrospect 7 The Compelling Case for Change 13 Methodology 17 Current Governance Reality 19 Principles and Criteria for Good Governance 27 Lessons Learned 29 Governance Options 35 Recommendations 47 Appendix and References (Bound Separately) Figures Figure 1 - Assiniboine Park Map 9 Figure 2 - Assiniboine Park & Forest Map 11 Figure 3 - Current Organizational Structure 21 Figure 4 - Best Practices Matrix 31 Figure 5 - Conservancy Option I 39 Figure 6 - Conservancy Option II 43 Figure 7 - Criteria/Models Matrix 45 Assiniboine Park Governance Study - February 2006 (Revised) i Overview In April, 2005, Assiniboine Park Enterprise (“APE”) mandated The Acumen Group in collaboration with Hilderman Thomas Frank Cram, and their team (“the Project Team”) to complete a governance review regarding Assiniboine Park (“the Park”) and make recommendations on options for its future leadership and organization. This report is organized into nine sections, the principal seven of which include: • The Compelling Case for Change: while an attractive physical presence, the Park is long overdue for an updated strategic plan, contemporary fundraising program, and modernized organizational structure to revitalize its luster and status as a tourist destination for the city and the province. • Current Governance Reality: a summary of how the Park is organized now, including the role of the City of Winnipeg (“the City”) and its various functional contributors, the different not-for-profit organizations and their leadership roles within the Park, and a strengths/weaknesses/opportunities/threats (“SWOT”) analysis of the present governance situation. -

History of the Winnipeg Park Patrol 120 Years of Policing Winnipeg's Parks 1897-2017

HISTORY OF THE WINNIPEG PARK PATROL 120 YEARS OF POLICING WINNIPEG'S PARKS 1897-2017 Researched and written by Sergeant John Burchill(retired) Winnipeg has more parks per capita than any other city in North America. With over 900 residential parks and 12 major Regional parks, Winnipeg has more than 10,260 acres of parkland. Although Winnipeg has an abundance of green space, it still enjoys some of the safest parks throughout Canada, which can be attributable to the efforts of Winnipeg's Park Patrol, formerly known as the Park Police. Although they were never listed in the national police directory, with 14 sworn members at its height, Winnipeg's Park Park Police - 1987, John Burchill Police were at one time one of the larger quasi-municipal police services in Manitoba. Their members are fully trained, sworn peace officers, who meet the same hiring and training standards as members of the Winnipeg Police Service. In fact, all full-time members of the Park Police were graduates of the Winnipeg Police Academy. With offices formerly located in Assiniboine Park, Kildonan Park and Kings Park, the Winnipeg Park Police operated primarily as one-officer units and provided 7-days a week coverage to most of the major regional parks and operated on a 24-hour a day schedule out of Assiniboine Park. In addition to three marked cruiser cars and an unmarked traffic unit, the Winnipeg Park Police also operated a bike patrol during large special events. Today they are known as the Park Patrol however they can trace their history back 115 years to 1897 when the Public Parks Board hired their first Special Constable. -

MAKING Our MARK

MAKING our MARK 2016/2017 Annual Report 2 MAKING OUR MARK TABLE of CONTENTS 4 Message from the Board Chair 5 Message from the President & CEO 6 About Travel Manitoba 7 Manitoba Tourism Indicators Summary 9 Content Marketing Campaigns 12 Research and Market Intelligence – Key Findings 13 Making our Mark in International Markets 14 • United Kingdom 18 • Germany 22 • United States 25 • China 28 • Australia 30 • France 32 • Canada 35 Visitor Services 36 Digital Marketing Statistics 40 Fishing and Hunting 42 Campaign Recognition 43 Aligning Partners and Unifying the Tourism Industry 44 Our Partners 47 Meetings, Conventions, Events and Incentive Travel 48 Board of Directors 49 Travel Manitoba Staff 51 Financial Statements Cover photo: Clear Lake Country/Austin MacKay 2016/2017 ANNUAL REPORT 3 MESSAGE from the BOARD CHAIR There is an often coined phrase, “Build it and they will come”. The results speak for themselves in this report: consistently In the past several years, the Manitoba tourism industry has done higher traffic from the US into Manitoba; more experiences listed its part, with the opening of new, world class attractions like the with key trade operators; more consumer engagement on our Canadian Museum for Human Rights, Assiniboine Park’s Journey websites and social channels; all leading to increased visitation to Churchill, Thermëa Nordic spa, Upper Fort Garry and many to Manitoba and increased spending in our province. more. But that is only part of the equation. In tourism, once it is But there is much more we can do, and now, with sustainable built, it must also be marketed. -

2019 Annual Report Mission the Assiniboine Park Conservancy Exists to Enhance the Assiniboine Park Experience for Present and Future Generations

2019 Annual Report Mission The Assiniboine Park Conservancy exists to enhance the Assiniboine Park experience for present and future generations. 1 Vision 2 Capital Development and Refurbishment 3 Zoo News 4 New Initiatives 4 Awards and Recognition 6 Capital Campaign Highlights 7 Education Programs 8 Conservation and Research 9 Sustainability Initiatives 10 Community Events and Engagement PHOTOS, COVER - Family admires polar bear display at Zoo 11 Staff and Volunteer Resources Lights Festival; BELOW - Visitors enjoy summer entertainment 12 Financial Statements at the Lyric Theatre (Mike Peters, courtesy of Tourism 16 Donor Listing Winnipeg). OPPOSITE - Margaret Redmond (President & CEO) and Hartley Richardson (Chair, Board of Directors). CELEBRATING A DECADE OF TRANSFORMATION In 2009, the Assiniboine Park Conservancy unveiled a visionary redevelopment plan that has transformed Assiniboine Park and Zoo. Ten years later, as we look back on the decade, we are reminded of the many exciting milestones we have celebrated together, including: • January 2011 opening of the expanded Riley Family Duck Pond • May 2011 opening of the Nature Playground and Streuber Family Children’s Garden • June 2011 opening of the Shirley Richardson Butterfly Garden • November 2011 opening of the Qualico Family Centre and Park Café • January 2012 opening of the Leatherdale International Polar Bear Conservation Centre • February 2013 opening of the Tundra Grill and Polar Playground • October 2013 first orphaned polar bear cub (Aurora) arrives at the Zoo • July 2014 opening of the Journey to Churchill exhibit • August 2015 opening of the McFeetors Heavy Horse Centre • September 2016 re-opening of The Pavilion art galleries and launch of WAG@ThePark • July 2017 sod-turning for The Leaf and Canada’s Diversity Gardens, attended by Prime Minister Trudeau, Premier Pallister, and Mayor Bowman We are now in the final major phase of this historic redevelopment. -

Go…To the Waterfront, Represents Winnipeg’S 20 Year Downtown Waterfront Vision

to the Waterfront DRAFT Go…to the Waterfront, represents Winnipeg’s 20 year downtown waterfront vision. It has been inspired by Our Winnipeg, the official development and sustainable 25-year vision for the entire city. This vision document for the to the downtown Winnipeg waterfront is completely aligned with the Complete Communities strategy of Our Winnipeg. Go…to the Waterfront provides Waterfront compelling ideas for completing existing communities by building on existing assets, including natural features such as the rivers, flora and fauna. Building upon the principles of Complete Communities, Go…to the Waterfront strives to strengthen and connect neighbourhoods with safe and accessible linear park systems and active transportation networks to each other and the downtown. The vision supports public transit to and within downtown and ensures that the river system is incorporated into the plan through all seasons. As a city for all seasons, active, healthy lifestyles 2 waterfront winnipeg... a 20 year vision draft are a focus by promoting a broad spectrum of “quality of life” infrastructure along the city’s opportunities for social engagement. Sustainability waterfront will be realized through the inclusion of COMPLETE COMMUNITIES is also a core principle, as the vision is based on economic development opportunities identified in the desire to manage our green corridors along this waterfront vision. A number of development our streets and riverbank, expand ecological opportunities are suggested, both private and networks and linkages and ensure public access public, including specific ideas for new businesses, to our riverbanks and forests. Finally, this vision infill residential projects, as well as commercial supports development: mixed use, waterfront living, and mixed use projects. -

Is the Assiniboine Zoo Free on Canada Day

Is the assiniboine zoo free on canada day click here to download Celebrate our nation's birthday on July 1 at the Canad Inns Picinic in the Park. Enjoy live music and entertainment at the Lyric Theatre, free birthday cake and. Polar Bears International has created a new earth awareness day, Arctic Sea Ice Visit the Parks Canada outreach education team at the Assiniboine Park Zoo. Join us for GEOCACHING DAY at Assiniboine Park Zoo this Saturday, September Sat AM UTC · Assiniboine Park & Zoo · Winnipeg, MB, Canada. Canada Day Fireworks; Winnipeg Canada Day Weekend; Canada Day Celebrations . Crescent Drive Park, Crescent Dr, Winnipeg. Free. The Forks is boasting its biggest Canada Day celebration thanks to The first people in the zoo each day will get a free polar bear token. The Assiniboine Park Zoo is celebrating Canada's th birthday with Each day from July 1 to 3, the first visitors will receive a free polar. Canada Where to celebrate Canada Day in Winnipeg The Assiniboine Park Zoo is hosting events through the weekend including The St. Boniface Museum and Fort Gibraltar will have free admission and a number of. Canada Day? Read our Top Things to Do in Winnipeg on Canada Day article. Grant Park Shopping Centre, Saturday, July 1: Closed. In celebration of our great nation, Assiniboine Park Zoo will host Canada Day festivities on July long weekend. Visitors can enjoy a festive. Canada Day is being celebrated far and wide this year to mark the at the Assiniboine Park Zoo each day (July ) will receive a free. -

1. Assiniboine River Corridor Development Precedents

5.2 PHASE 2 BRAINSTORMING AND CONSENSUS BUILDING ASSINIBOINE RIVER CORRIDOR PRECEDENTS AND COMMUNITY INPUT RESULTS 1. ASSINIBOINE RIVER CORRIDOR DEVELOPMENT PRECEDENTS The following regional, national, and international precedents for sustainable and resilient waterfront development were used in the creation of the workshop slider worksheets and in the development of Master Plan ideas for the Brandon Assiniboine River Corridor Master Plan. Regional: Wascana Lake Waterfront (Regina), South Saskatchewan River Corridor (Saskatoon), Winter Cities Strategy (Edmonton), Go to the Waterfront Initiative Winnipeg (Red & Assiniboine Rivers) Bismarck River Corridor Parks System (Missouri River, North Dakota), Fargo River Corridor System (Red River North), Grand Forks River Corridor, Bois des Esprit (Seine River Management Plan Winnipeg), Minneapolis Riverfront Plan Rivers First Initiative (Mississippi River), Adrenaline Adventures and A Maze In Corn Adventure Sport Outfitters Winnipeg, Winnipeg Floodway 100 Year Management Plan. National: River Access Strategy Edmonton (North Saskatchewan River), Ottawa River Integrated Development Plan, Thunder Bay Waterfront Development, Guelph River Corridor Development, University of Waterloo Native Riverbank Corridor Regeneration Plan, Oakville Waterfront Plan. International: Ravensbourne River Corridor Improvement Plan (Thames/England), San Antonio River Corridor and Canals, Brent River Corridor Development Plan (Greater London), Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan, Oslo Waterfront, Seine River South Bank Redevelopment -

694 Academy Road Archibald & Mary Wright House

694 ACADEMY ROAD ARCHIBALD & MARY WRIGHT HOUSE City of Winnipeg Historical Buildings Committee Researcher: M. Peterson April 2008 694 ACADEMY ROAD – ARCHIBALD & MARY WRIGHT HOUSE Notes on Date of Construction: There is conflicting information about the actual construction date of this house – 1881, 1891 and 1912 – the earlier date comes from Historical Buildings Committee information from the 1970s, the middle date from the realtor’s website and the last date comes from the City of Winnipeg Assessment Department. The following information has been gleaned from various sources uncovered to date: • The house actually sits on what was originally River Lot 1 St. Charles. Archibald Wright arrived in the area in the late 1860s and it is known from Land Titles Office records that he and his wife Mary owned the land on which this building stands from the 1870s (River Lots 60-63 Parish of St. Boniface and River Lots 1 and 2 Parish of St. Charles). These records only describe land – buildings are not included; • City of Winnipeg Tax Roll information also shows the couple owning vacant River Lots 60, 62 and 63 and part of 61 Parish of St. Boniface in the 1880s and beyond. River Lots 1 and 2 St. Charles are outside the City boundaries. In 1913, Mary Wright is listed as the owner/occupant of a home and stable on Godfrey Avenue, Lots 14, 15 and 21/22, Plan 1374, Block 7, 60/63 St. Boniface (house actually sits on Lot 15); • Canada Census data from 1901, 1906 and 1911 all list Archibald Wright and his family as living in this area: “Assiniboia” (1901), “Parishes of St. -

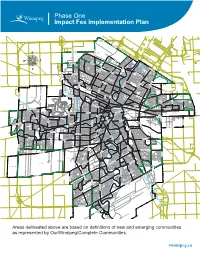

Impact Fee Implementation Plan

Phase One Impact Fee Implementation Plan ROSSER-OLD KILDONAN AMBER TRAILS RIVERBEND LEILA NORTH WEST KILDONAN INDUSTRIAL MANDALAY WEST RIVERGROVE A L L A TEMPLETON-SINCLAIR H L A NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL INKSTER GARDENS THE MAPLES V LEILA-McPHILLIPS TRIANGLE RIVER EAST MARGARET PARK KILDONAN PARK GARDEN CITY SPRINGFIELD NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL PARK TYNDALL PARK JEFFERSON ROSSMERE-A KILDONAN DRIVE KIL-CONA PARK MYNARSKI SEVEN OAKS ROBERTSON McLEOD INDUSTRIAL OAK POINT HIGHWAY BURROWS-KEEWATIN SPRINGFIELD SOUTH NORTH TRANSCONA YARDS SHAUGHNESSY PARK INKSTER-FARADAY ROSSMERE-B BURROWS CENTRAL ST. JOHN'S LUXTON OMAND'S CREEK INDUSTRIAL WESTON SHOPS MUNROE WEST VALLEY GARDENS GRASSIE BROOKLANDS ST. JOHN'S PARK EAGLEMERE WILLIAM WHYTE DUFFERIN WESTON GLENELM GRIFFIN TRANSCONA NORTH SASKATCHEWAN NORTH DUFFERIN INDUSTRIAL CHALMERS MUNROE EAST MEADOWS PACIFIC INDUSTRIAL LORD SELKIRK PARK G N LOGAN-C.P.R. I S S NORTH POINT DOUGLAS TALBOT-GREY O R C PEGUIS N A WEST ALEXANDER N RADISSON O KILDARE-REDONDA D EAST ELMWOOD L CENTENNIAL I ST. JAMES INDUSTRIAL SOUTH POINT DOUGLAS K AIRPORT CHINA TOWN C IVIC CANTERBURY PARK SARGENT PARK CE TYNE-TEES KERN PARK NT VICTORIA WEST RE DANIEL McINTYRE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NORTH ST. BONIFACE REGENT MELROSE CENTRAL PARK SPENCE PORTAGE & MAIN MURRAY INDUSTRIAL PARK E TISSOT LLIC E-E TAG MISSION GARDENS POR TRANSCONA YARDS HERITAGE PARK COLONY SOUTH PORTAGE MISSION INDUSTRIAL THE FORKS DUGALD CRESTVIEW ST. MATTHEWS MINTO CENTRAL ST. BONIFACE BUCHANAN JAMESWOOD POLO PARK BROADWAY-ASSINIBOINE KENSINGTON LEGISLATURE DUFRESNE HOLDEN WEST BROADWAY KING EDWARD STURGEON CREEK BOOTH ASSINIBOIA DOWNS DEER LODGE WOLSELEY RIVER-OSBORNE TRANSCONA SOUTH ROSLYN SILVER HEIGHTS WEST WOLSELEY A NORWOOD EAST STOCK YARDS ST. -

Celebrate 150 Spend Time in the Great Outdoors

150 Things to Do in Manitoba CELEBRATE 150 1. Unite 150 Head to the Manitoba Legislative Building this summer for an epic (and FREE) concert that celebrates Manitoba 150. There will be 3 stages with BIG acts from across Canada. Can’t make it? The entire spectacle will be streamed live across Manitoba. *BONUS: Download the Manitoba 150 app to explore new landmarks throughout the province, with the chance to win some amazing prizes. 2. Tour 150 The Winnipeg Art Gallery is hitting the road in 2020 to bring a mini- gallery on wheels to communities and towns throughout the province. SPEND TIME IN THE GREAT OUTDOORS Pinawa Channel 3. Float down the Pinawa Channel If floating peacefully down a lazy river seems appealing to you this summer, don’t miss the opportunity to take in the gorgeous scenery of the Pinawa Channel! There are two companies to rent from: Wilderness Edge Resort and Float & Paddle. 4. Learn to winter camp You may be a seasoned camper in the summer months - but have you tried it in the cold nights of winter? Wilderland Adventure Company is offering a variety of traditional winter camping experiences in Sandilands Provincial Forest, Whiteshell Provincial Park and Riding Mountain National Park. oTENTik at Riding Mountain National Park Pinawa Dam Photo Credit: Max Muench 5. Take a self-guided tour of Pinawa Dam Provincial Park Get a closer look at Manitoba’s first year-round generating plant on the Dam Ruins Walk in Pinawa Dam Provincial Park. There are 13 interpretive signs along the way! 6. -

Wonderful Winnipeg “Another Wonderful R&J Trip

Wonderful Winnipeg “Another wonderful R&J Trip. The variety of activities offer something for everyone. Everyone is so accommodating. I meet the greatest new friends on my R&J Trips!” Bonnie, Waite Park - Wonderful Winnipeg 2018 Winnipeg, Manitoba Winnipeg, Fort Gibraltar August 13 - 17, 2019 (5 days) MAP AT A GLANCE HIGHLIGHTS Manitoba Historic Fort Garry Hotel in Downtown Winnipeg Winnipeg Hutterite Colony Tour & Home-Cooked Lunch Minnesota Winnipeg City Tour with Local Expert Guide Live performance at the Outdoor Rainbow Stage of “Cinderella” Canadian Museum for Human Rights The Forks at Leisure The Royal Canadian Mint Polar Bear Exhibit A special visit to the Hutterite Colony Assiniboine Park Folklorama & Cultural Dinner English Gardens at Assiniboine Park Fort Gibraltar R&J extends a special invitation for YOU to come & see why we feel Winnipeg is truly a special gem of a city that is often overlooked! Join us, we promise you’ll be pleasantly surprised! 2018 R&J Group at “Journey to Churchill” at the Assiniboine Park Zoo 140 Experience 3 Folklorama Pavilions Polar Bear Hugs included!! “Journey to Churchill” Stay 4 nights at the Historic Fort Garry Hotel where fresh coffee is delivered to your room! Royal Canadian Mint - 2010 Vancouver Olympic Medals! Day 1 - Home to Winnipeg you may choose to visit the Forks, Winnipeg’s number one tourist With excitement, we’ll be on the way to Winnipeg and check into destination, located at the junction of the Assiniboine & mighty Red our hotel and freshen up before an included welcome dinner. For Rivers. The Forks has been a meeting place for over 6,000 years for the next four nights we are guests at the Historic Fort Garry Hotel early Aboriginal trading, fur trading, Scottish settlers, and tens of with modern-day style and conveniently located in the heart of thousands of immigrants. -

Becoming the Wolf Capital of the World

masterpiece that dominates Thompson’s landscape and can be seen a mile away. Within a year of the mural’s comple- tion, Spirit Way Inc. (SWI) was flooded with public interest and media attention from across Canada by people who have a love and fascination with wolves. Initially, SWI was © Volker Beckmann © Volker puzzled by the interest, but quickly realized there was an opportunity here for tourism and economic development, as well as a further cause: to protect a much maligned species. Thompson is surrounded by wilderness boreal forest and an unknown number of wolves. Thompson residents and homeowners living along lakes in the area are generally not bothered by wolves and have a tolerant attitude. After the wolf mural was completed, SWI created over 50 beauti- fully painted 7.5 ft-tall concrete wolf statues and situated them throughout Manitoba. A large rock-face sculpture of howling wolves was also carved in Thompson. The wolf theme is now clearly evident in the community. Becoming the Humans versus Wolves Wolf Capital of the World Throughout most of recorded history, human/wolf conflicts by 2015 have triggered culling and bounties in many countries, leading to near extermination by the late 1900s. As apex n 2004, a group of volunteers in Thompson, Manitoba predators, wolves compete with hunters and ranchers for decided to create a tourist attraction that would generate deer, elk, moose, reindeer and even cattle and sheep. new pride in the community. “Spirit Way”, a 2.5 km Canada’s boreal forest supports the largest grey wolf I population in the world with estimated numbers around walking pathway through the community with 16 points of interest would showcase various aspects of a northern 50,000.