Lower Snake River Dams Stakeholder Engagement Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AFS Policy Statement #32: STUDY REPORT on DAM REMOVAL for the AFS RESOURCE POLICY COMMITTEE (Full Text)

AFS Policy Statement #32: STUDY REPORT ON DAM REMOVAL FOR THE AFS RESOURCE POLICY COMMITTEE (Full Text) (DRAFT #7: 10/05/01, J. Haynes, Editor) (DRAFT #8: 02/23/03, T. Bigford) (DRAFT #9: 03/18/03, H. Blough) (DRAFT #10: 09/23/03, T. Bigford) (DRAFT #11: 09/25/03, T. Bigford) (DRAFT #12: 10/31/03, T. Bigford) (DRAFT #13: 1/9/04, T. Bigford) (DRAFT #14: 7/7/04, T. Bigford) (DRAFT #15: 7/18/04, T. Bigford) (DRAFT #16: 11/20/04, T. Bigford) 2003-2004 Resource Policy Committee Heather Blough, Co-Chair, Kim Hyatt, Co-Chair, Mary Gessner, Victoria Poage, Allan Creamer, Chris Lenhart, Jamie Geiger, Jarrad Rosa, Wilson Laney, Tom Bigford, Danielle Pender, Tim Essington with assistance from Jennifer Lowery 2002-2003 Resource Policy Committee Heather Blough, Co-Chair, Thomas E. Bigford, Co-Chair Allan Creamer, Bob Peoples, Chris Lenhart, Maria La Salete Bernardino Rodrigues, Jamie Geiger, Jarrad Rosa, Wilson Laney, Kim Hyatt, Danielle Pender 2001-2002 Resource Policy Committee Tom Bigford, Chair, Heather Blough, Vice Chair, Jim Francis, Bill Gordon, Judy Pederson, Larry Simpson, Jarrad Kosa, Jaime Geiger, Bob Peoples, Maria La Salete Bernardino Rodrigues, Chris Lenhart 2000-2001 Coordinating Committee James M. Haynes, Chair, R. Duane Harrell, Christine M. Moffitt (ex officio), tc "James M. Haynes, Chair, R. Duane Harrell, Christine M. Moffitt (ex officio), Gary E. Whelan, Maureen Wilson, James M. Haynes, Chair 1999-2000 Study Committee Larry L. Olmsted, Chair, Donald C. Jackson, Peter B. Moyle,Stephen G. Rideout November 20, 2004 Introduction This study report provides background information to support a recommendation by the American Fisheries Society’s (AFS) Resource Policy Committee to develop a Dam Removal Policy Statement for consideration by the Governing Board and the full membership. -

Environmental Benefits of Dam Removal

A Research Paper by Dam Removal: Case Studies on the Fiscal, Economic, Social, and Environmental Benefits of Dam Removal October 2016 <Year> Dam Removal: Case Studies on the Fiscal, Economic, Social, and Environmental Benefits of Dam Removal October 2016 PUBLISHED ONLINE: http://headwaterseconomics.org/economic-development/local-studies/dam-removal-case-studies ABOUT HEADWATERS ECONOMICS Headwaters Economics is an independent, nonprofit research group whose mission is to improve community development and land management decisions in the West. CONTACT INFORMATION Megan Lawson, Ph.D.| [email protected] | 406-570-7475 P.O. Box 7059 Bozeman, MT 59771 http://headwaterseconomics.org Cover Photo: Whittenton Pond Dam, Mill River, Massachusetts. American Rivers. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 MEASURING THE BENEFITS OF DAM REMOVAL ........................................................................................... 2 CONCLUSION ................................................................................................................................................. 5 CASE STUDIES WHITTENTON POND DAM, MILL RIVER, MASSACHUSETTS ........................................................................ 11 ELWHA AND GLINES CANYON DAMS, ELWHA RIVER, WASHINGTON ........................................................ 14 EDWARDS DAM, KENNEBEC RIVER, MAINE ............................................................................................... -

Marmot Dam Removal Geomorphic Monitoring & Modelling Project

MARMOT DAM REMOVAL GEOMORPHIC MONITORING & MODELING PROJECT ANNUAL REPORT June 2008 – May 2009 Prepared for: Sandy River Basin Watershed Council PO Box 868 Sandy OR 97055 Prepared by: Charles Podolak Johns Hopkins University Department of Geography & Environmental Engineering 3400 N. Charles St, Baltimore MD 21218 Smokey Pittman Graham Matthews & Associates P.O. Box 1516, Weaverville, CA, 96093 June 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to sincerely thank all who assisted with the Marmot Dam Removal Geomorphic Monitoring & Modeling Project: Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board – funding Johns Hopkins University & The National Center for Earth-surface Dynamics (NCED) Peter Wilcock Project Advisor Daniela Martinez Graduate Assistant NCED & National Science Foundation Research Experience for Undergraduates Kim Devillier Intern Dajana Jurk Intern Cecilia Palomo Intern Tim Shin Intern Katie Trifone Intern Graham Matthews & Associates Graham Matthews GMA Principle Investigator Logan Cornelius Streamflow and Sediment Sampling Cort Pryor Streamflow and Sediment Sampling Brooke Connell Topographic Surveys Keith Barnard Topographic Surveys/Survey Data Analysis Sandy River Basin Watershed Council Russ Plaeger Director U.S. Geological Survey Jon Major Jim O’Connor Rose Wallick Mackenzie Keith U.S. Forest Service Connie Athman Gordon Grant Portland General Electric David Heinzman John Esler Tim Keller Tony Dentel Metro Parks Bill Doran Landowners Mary Elkins David Boos MARMOT DAM REMOVAL GEOMORPHIC MONITORING & MODELING PROJECT – 2009 ANNUAL REPORT ii -

Fielder and Wimer Dam Removals Phase I

R & E Grant Application Project #: 13 Biennium 13-054 Fielder and Wimer Dam Removals Phase I Project Information R&E Project $58,202.00 Request: Match Funding: $179,126.00 Total Project: $237,328.00 Start Date: 4/26/2014 End Date: 6/30/2015 Project Email: [email protected] Project 13 Biennium Biennium: Organization: WaterWatch of Oregon (Tax ID #: 93-0888158) Fiscal Officer Name: John DeVoe Address: 213 SW Ash Street, Suite 208 Portland, OR 97204 Telephone: 503-295-4039 x1 Email: [email protected] Applicant Information Name: Bob Hunter Email: [email protected] Past Recommended or Completed Projects This applicant has no previous projects that match criteria. Project Summary This project is part of ODFW’s 25 Year Angling Plan. Activity Type: Passage Summary: The project is to solve the fish passage problems associated with Fielder and Wimer Dams by removing the aging structures. This grant will provide funding for the pre-implementation mapping, assessments, analyses, design work, permitting, construction drawings, and preparation of bid packages needed for removal of these two dams. This Phase I pre-implementation work will be followed by Phase II implementation of the dam removal and site restoration plans that will be developed in this first phase. Objectives: Fielder and Wimer Dams are located on Evans Creek, an important salmon and Project #: 13-054 Last Modified/Revised: 4/11/2014 3:16:13 PM Page 1 of 12 Fielder and Wimer Dam Removals Phase I steelhead spawning tributary of the Rogue River. Both dams are listed in the top ten in priority statewide on ODFW’s 2013 Statewide Fish Passage Priority List. -

Item F – Klamath Dam Removal - Contingency Funding March 9-10, 2021 Board Meeting

Kate Brown, Governor 775 Summer Street NE, Suite 360 Salem OR 97301-1290 www.oregon.gov/oweb (503) 986-0178 Agenda Item F supports OWEB’s Strategic Plan priority #3: Community capacity and strategic partnerships achieve healthy watersheds, and Strategic Plan priority 7: Bold and innovative actions to achieve health in Oregon’s watersheds. MEMORANDUM TO: Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board FROM: Meta Loftsgaarden, OWEB Executive Director Richard Whitman, DEQ Director SUBJECT: Agenda Item F – Klamath Dam Removal - Contingency Funding March 9-10, 2021 Board Meeting I. Introduction Removal of the four PacifiCorp dams along the Klamath River in Oregon and California that block fish passage has been a priority of multiple governors in both states for over a decade. After extensive work by the Klamath River Renewal Corporation and its contractors (in partnership with states, tribes, federal agencies, irrigators, conservation groups, and many others), there is now a clear path to completing dam removal in 2023. This staff report updates the board on the dam removal project and asks for a general indication of board support in the unlikely event that additional funding is needed to complete restoration work following dam removal. II. Background PacifiCorp owns and operates four hydro-electric dams on the Klamath River, three in California and one in Oregon. PacifiCorp has decided to that it is in the best interest of the company and its customers to stop operating the dams rather than spending substantial amounts on improvements likely to be needed if they were to continue generating power. PacifiCorp has agreed to transfer ownership of the dams to the Klamath River Restoration Corporation, which in turn has contracted with Kiewit Infrastructure -- one of the nation’s most experienced large project construction firms – which will remove the dams and restore the river to a free-flowing condition. -

Lesson 1 the Columbia River, a River of Power

Lesson 1 The Columbia River, a River of Power Overview RIVER OF POWER BIG IDEA: The Columbia River System was initially changed and engineered for human benefit Disciplinary Core Ideas in the 20th Century, but now balance is being sought between human needs and restoration of habitat. Science 4-ESS3-1 – Obtain and combine Lesson 1 introduces students to the River of Power information to describe that energy curriculum unit and the main ideas that they will investigate and fuels are derived from natural resources and their uses affect the during the eleven lessons that make up the unit. This lesson environment. (Clarification Statement: focuses students on the topics of the Columbia River, dams, Examples of renewable energy and stakeholders. Through an initial brain storming session resources could include wind energy, students record and share their current understanding of the water behind dams, and sunlight; main ideas of the unit. This serves as a pre-unit assessment nonrenewable energy resources are fossil fuels and fissile materials. of their understanding and an opportunity to identify student Examples of environmental effects misconceptions. Students are also introduced to the main could include loss of habitat to dams, ideas of the unit by viewing the DVD selection Rivers to loss of habitat from surface mining, Power. Their understanding of the Columbia River and the and air pollution from burning of fossil fuels.) stakeholders who depend on the river is deepened through the initial reading selection in the student book Voyage to the Social Studies Pacific. Economics 2.4.1 Understands how geography, natural resources, Students set up their science notebook, which they will climate, and available labor use to record ideas and observations throughout the unit. -

Snake River 1157 Wildlife Habitat Information to Inform the Plan- Ton, and Northeast Oregon

Snake River 1157 wildlife habitat information to inform the plan- ton, and northeast Oregon. +roughout its long ning decisions for renewable energy. history, volcanoes, flooding, and glaciers have Climate change impacts may be felt in the arid shaped the river and its shores. region; nitrogen deposits, atmospheric carbon +e Snake River plain was created by a volca- dioxide, and other changes will impact the grass- nic hotspot beneath Yellowstone National Park, lands. Climate change may impact the size of the which holds the headwaters and origin of the river. sagebrush areas, for example, which in turn con- Flooding as the glaciers retreated after the ice age stricts grouse and other birds and mammals liv- created the current landscape, including eroded ing in these habitats. canyons and valleys. Mountains and plains are typical terrain along the river. +e Snake River has P J. C more than 20 major tributaries, most of them in the mountains; Hells Canyon is the deepest river Further Reading gorge in North America. Cutright, Paul Russell. Lewis and Clark: Pioneering +e Snake River is home to salmon and steel- Naturalists . Lincoln: University of Nebraska head, which were central to the lives of the Nez Press, 2003. Perce and Shoshone, the dominant tribal nations Petersen, Keith C. River of Life, Channel of Death: before the Europeans came. People have lived Fish and Dams on the Lower Snake . Corvallis: along the Snake River for over 15,000 years. +e Oregon State University Press, 2001. Snake River may have been given its name by the Waring, Gwendolyn. L. A Natural History of Shoshones, as a hand signal made by the Shosho- the Intermountain West: Its Ecological and nes representing fish was misinterpreted by Euro- Evolutionary Story. -

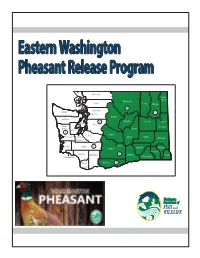

Eastern Washington Pheasant Release Program

Eastern Washington Pheasant Release Program Whatcom Pend Oreille Okanogan Skagit Ferry Stevens 2 Snohomish Clallam Mill Creek 1 Chelan Jeerson 4 Douglas Lincoln Spokane Kitsap King Grays Spokane Harbor Ephrata Mason 6 Kittitas Pierce Montesano Olympia Grant Adams Whitman Thurston Yakima Pacic Lewis 5 Franklin Yakima Gareld Columbia Cowlitz Skamania 3 Benton Asotin Wahkiakum Walla Walla Clark Klickitat 5 Vancouver EASTERN WASHINGTON PHEASANT ENHANCEMENT PROGRAM Over the past two decades Eastern Each year thousands of pheasants Eastern Washington Washington has been experiencing are released on lands accessible to Regional Offices: a decline in pheasant harvest. the public. The Eastern Washington Habitat loss has been identified as release sites are shown on the maps REGION 1 the leading factor for the decline. To in this pamphlet. Rooster pheasants (509) 892-1001 address the loss of habitat WDFW are released to supplement harvest. 2315 North Discovery Place initiated an aggressive habitat Birds are released for youth and Spokane Valley, WA 99216-1566 enhancement program. To fund general season openers. We do not this program the Legislature in 1997 provide other release dates because REGION 2 created the Eastern Washington we want to minimize crowding at (509) 754-4624 Pheasant Enhancement Fund. the release sites and promote hunter 1550 Alder St. NW ethics. Ephrata, WA 98823-9699 The Eastern Washington Pheasant Enhancement Fund is a dedicated To protect other wildlife species REGION 3 (509) 575-2740 funding source. The fund is including waterfowl and raptors, 1701 S 24th Ave. used solely for pheasant habitat non-toxic shot is required for all Yakima, WA 98902-5720 enhancement on public and private upland bird, dove and band-tailed lands and for the purchase of pigeon on all pheasant release sites REGION 5 rooster pheasants that are released statewide. -

History of Snake River Canyon Indicated by Revised Stratigraphy of Snake River Group Near Hagerman and King Hill, Idaho

History of Snake River Canyon Indicated by Revised Stratigraphy of Snake River Group Near Hagerman and King Hill, Idaho GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 644-F History of Snake River Canyon Indicated by Revised Stratigraphy of Snake River Group Near Hagerman and King Hill, Idaho By HAROLD E. MALDE With a section on PALEOMAGNETISM By ALLAN COX SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 644-F Lavaflows and river deposits contemporaneous with entrenchment of the Snake River canyon indicate drainage changes that provide a basis for improved understanding of the late Pleistocene history UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1971 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. A. Radlinski, Acting Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72-171031 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 40 cents (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-1128 CONTENTS Page page Abstract ___________________________________________ Fl Late Pleistocene history of Snake River_ _ F9 Introduction.______________________________________ 2 Predecessors of Sand Springs Basalt. 13 Acknowledgments --..______-__-____--__-_---__-_____ 2 Wendell Grade Basalt-________ 14 Age of the McKinney and Wendell Grade Basalts. _____ 2 McKinney Basalt. ____---__---__ 16 Correlation of lava previously called Bancroft Springs Bonneville Flood.________________ 18 Basalt_________________________________________ Conclusion___________________________ 19 Equivalence of pillow lava near Bliss to McKinney Paleomagnetism, by Allan Cox_________ 19 Basalt.._________________________ References cited._____________________ 20 ILLUSTRATIONS Page FIGURE 1. Index map of Idaho showing area discussed.______________________________________________________ F2 2. Chart showing stratigraphy of Snake River Group..____________________________._____--___-_-_-_-. -

Snake River Flow Augmentation Impact Analysis Appendix

SNAKE RIVER FLOW AUGMENTATION IMPACT ANALYSIS APPENDIX Prepared for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Walla Walla District’s Lower Snake River Juvenile Salmon Migration Feasibility Study and Environmental Impact Statement United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Pacific Northwest Region Boise, Idaho February 1999 Acronyms and Abbreviations (Includes some common acronyms and abbreviations that may not appear in this document) 1427i A scenario in this analysis that provides up to 1,427,000 acre-feet of flow augmentation with large drawdown of Reclamation reservoirs. 1427r A scenario in this analysis that provides up to 1,427,000 acre-feet of flow augmentation with reservoir elevations maintained near current levels. BA Biological assessment BEA Bureau of Economic Analysis (U.S. Department of Commerce) BETTER Box Exchange Transport Temperature Ecology Reservoir (a water quality model) BIA Bureau of Indian Affairs BID Burley Irrigation District BIOP Biological opinion BLM Bureau of Land Management B.P. Before present BPA Bonneville Power Administration CES Conservation Extension Service cfs Cubic feet per second Corps U.S. Army Corps of Engineers CRFMP Columbia River Fish Mitigation Program CRP Conservation Reserve Program CVPIA Central Valley Project Improvement Act CWA Clean Water Act DO Dissolved Oxygen Acronyms and Abbreviations (Includes some common acronyms and abbreviations that may not appear in this document) DREW Drawdown Regional Economic Workgroup DDT Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane EIS Environmental Impact Statement EP Effective Precipitation EPA Environmental Protection Agency ESA Endangered Species Act ETAW Evapotranspiration of Applied Water FCRPS Federal Columbia River Power System FERC Federal Energy Regulatory Commission FIRE Finance, investment, and real estate HCNRA Hells Canyon National Recreation Area HUC Hydrologic unit code I.C. -

Forest Plan Amendment No. 30 Clearwater National Forest Latah

Forest Plan AmendmentNo. 30 Clearwater National Forest Latah County, Idaho The purpose of Amendment No. 30 is to changethe water quality objectives in Appendix K of the Clearwater National Forest Plan for Little Boulder Creek, East Fork Potlatch River, and Ruby Creek, plus, add the Potlatch River. Currently the water quality objective for Little Boulder, East Fork Potlatch and Ruby Creek is "Minimum viable" and the fish speciesis listed as rainbow. Minimum Viable does not support the requirements of the Clean Water Act to provide fishable streams. It only provides a minimal population and does not reflect the listing of the species or importance of the area for spawning. Surveys have documented steelhead in Little Boulder, East Fork Potlatph Riyer, and Ruby Creek. Steelheadwas listed as a Threatened Species within the Snake River in 1997. The Potlatch River, a migratory channel for steelhead,had only been listed in Appendix K as a placeholder to indicate the watershed geography. Stream surveys have shown the river to have a C channel and steelheadas the fish species. Spawning occurs in the East Fork Potlatch, and rearing occurs in most of the tributaries of the Potlatch River. Since the Potlatch River is proposed as critical habitat for steelhead,the water quality objective is being changed from "Minimum Viable" to "High Fish" to follow the direction of the Clean Water Act and Endangered SpeciesAct. Also, as part of the high fish standard, threshold levels of sediment for the Potlatch River should not exceed 10 out of 30 years. Since the proposed changes are not significant, adoption of this amendmentwould not significantly change the forest-wide environmental impacts disclosed in the Clearwater National Forest Plan EIS. -

Chapter 7. Parks and Recreation Element

1 Chapter 7. Parks and Recreation Element 2 7.1. Introduction 3 Parks, recreational facilities, and open space are generally considered beneficial resources and 4 essential contributors to a community’s quality of life. Located within the County are a number 5 of different types of parks and recreational facilities. 6 The County has not traditionally served as a provider of park and recreation facilities. Local 7 cities, private agencies, federal agencies, and schools have an established history of furnishing 8 these services. 9 The purpose of this element is to evaluate parks and recreation facilities in the County and to 10 develop goals and policies that guide management and coordination of them. 11 7.1.1. Applicable Growth Management Act Goals 12 GMA planning goals that are applicable to the Parks and Recreation Element include the 13 following: 14 . Open space and recreation. Retain open space, enhance recreational opportunities, conserve 15 fish and wildlife habitat, increase access to natural resource lands and water, and develop 16 parks and recreation facilities (Revised Code of Washington [RCW] 36.70A.020(9)). 17 . Public facilities and services. Ensure that those public facilities and services necessary to 18 support development shall be adequate to serve the development at the time the development 19 is available for occupancy and use without decreasing current service levels below locally 20 established minimum standards (RCW 36.70A.020(12)). 21 . Historic preservation. Identify and encourage the preservation of lands, sites, and structures 22 that have historical or archaeological significance (RCW 36.70A.020(13)). 23 Goals described in the Shoreline Management Act (SMA) also support the Parks and Recreation 24 Element.