Regional Formation and Development Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-Commencement-Program.Pdf

One Hundred and Sixty-Second Annual Commencement JUNE 19, 2020 One Hundred and Sixty-Second Annual Commencement 11 A.M. CDT, FRIDAY, JUNE 19, 2020 2982_STUDAFF_CommencementProgram_2020_FRONT.indd 1 6/12/20 12:14 PM UNIVERSITY SEAL AND MOTTO Soon after Northwestern University was founded, its Board of Trustees adopted an official corporate seal. This seal, approved on June 26, 1856, consisted of an open book surrounded by rays of light and circled by the words North western University, Evanston, Illinois. Thirty years later Daniel Bonbright, professor of Latin and a member of Northwestern’s original faculty, redesigned the seal, Whatsoever things are true, retaining the book and light rays and adding two quotations. whatsoever things are honest, On the pages of the open book he placed a Greek quotation from the Gospel of John, chapter 1, verse 14, translating to The Word . whatsoever things are just, full of grace and truth. Circling the book are the first three whatsoever things are pure, words, in Latin, of the University motto: Quaecumque sunt vera whatsoever things are lovely, (What soever things are true). The outer border of the seal carries the name of the University and the date of its founding. This seal, whatsoever things are of good report; which remains Northwestern’s official signature, was approved by if there be any virtue, the Board of Trustees on December 5, 1890. and if there be any praise, The full text of the University motto, adopted on June 17, 1890, is think on these things. from the Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Philippians, chapter 4, verse 8 (King James Version). -

Action Plan for Vidzeme Region

Cult ural Routes as Investments for Growth and Jobs Action Plan for Vidzeme Region December 2018 Cultural Routes as Investment for Growth and Jobs _________________________ © Cult-RInG Project Partnership and Vidzeme Tourism Association, Latvia This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Cult-RInG Project Communication and the respective partner: Vidzeme Tourism Association. Citation: Interreg Europe Project Cult-RInG Action Plan, Vidzeme Tourism Association, Latvia Cult-RInG project communication unit would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source on e-mail: [email protected] Disclaimer This document has been prepared with the financial support of Interreg Europe 2014-2020 interregional cooperation programme. The content of the document is the sole responsibility of Vidzeme Tourism Association and in no way reflect the views of the European Union institutions, nor the Managing Authority of the Programme. Any reliance or action taken based on the information, materials and techniques described within this document are the responsibility of the user. The Cult-RInG project partnership assumes no responsibility for any consequences arising from use of the information described within this document. December 2018 Action Plan 2 Cultural Routes as Investment for Growth and Jobs Interreg Europe Programme Interreg Europe Programme of interregional cooperation helps regional and local governments across Europe to develop and deliver better policy. -

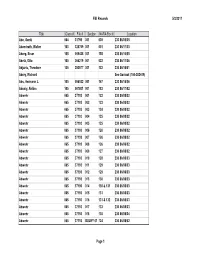

5/3/2011 FBI Records Page 1 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box

FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abe, Genki 064 31798 001 039 230 86/05/05 Abendroth, Walter 100 325769 001 001 230 86/11/03 Aberg, Einar 105 009428 001 155 230 86/16/05 Abetz, Otto 100 004219 001 022 230 86/11/06 Abjanic, Theodore 105 253577 001 132 230 86/16/01 Abrey, Richard See Sovloot (100-382419) Abs, Hermann J. 105 056532 001 167 230 86/16/06 Abualy, Aldina 105 007801 001 183 230 86/17/02 Abwehr 065 37193 001 122 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 002 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 003 124 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 004 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 005 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 006 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 007 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 008 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 009 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 010 128 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 011 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 012 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 013 130 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 014 130 & 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 015 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 016 131 & 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 017 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 018 135 230 86/08/04 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 01 124 230 86/08/02 Page 1 FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 20 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 35 134 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr -

Kent County Naturalization Name Index, Aalbers, A

Kent County Naturalization Name Index Last name First name Middle name Volume Page Fir Sec Aalbers Aalbers V62 4 Aalbers Aalbert V24 141 Aalddriks Antonie V16 75 Aalderink John K. V16 355 Aaldrick Matthew V16 308 Aardem Arie V16 304 Aardema Klaas V17 27 Aarnouds Pieter V6 8 Aarnoudse Marenus V15 503 Abagis Chas V30 130 Abbas Sain Allez V49 265 Abbelma Joseph B1 F5 Abbelma Joseph V2 564 Abbott Frank V27 92 Abbott John V45 36 Abbott John V68 33 Abdella Salik V46 117 Abdo Ahamad V29 1 Abdoo Mike V41 168 Abeaf Moses V17 391 Abeaf Moses V17 394 Abel Frederick FW B1 F1 Abel Gustav B1 F4 Abel Gustav V2 540 Abel John W. V5 70 Abel Ludwig V8 134 Friday, January 19, 2001 Page 1 of 1325 Last name First name Middle name Volume Page Fir Sec Abella Salih V68 85 Abezi Albert V25 76 Aboabsee Theab V74 40 Aboasee Theab V18 150 Abood N. B1 F5 Abood Nemy V3 90 Abraham John V17 381 Abrahamson Charles Y. B7 200 Abram John B1 F1 Abramson Morris B1 F3 Abraursz Abram Peter V27 159 Abromaitis Louis V27 381 Abromaitis Louis V67 90 Absmaier Carl V77 4 Accardi Guiseppe V50 79 Acheson John V16 616 Achille Minciotti V51 142 Achtenhof Jakob V15 145 Achter Jan V17 200 Achterhof Henri B1 F1 Achterhof Johannes V15 500 Achterhof Matheus B1 F1 Achtjes John B7 107 Ackermann Joseph V15 282 Acton John C. B7 222 Adair David G. V15 335 Adair Joseph V15 335 Adalphson Emil V18 197 Friday, January 19, 2001 Page 2 of 1325 Last name First name Middle name Volume Page Fir Sec Adam Frickartz Heinrich V41 279 Adama Jelle V22 176 Adamawiczus Baltris V37 155 Adamczak Peter V38 245 Adamczyk Wladyslaw V35 291 Adams Edward John V24 70 Adams Frank B1 F2 Adams George W. -

4 F\Ihli«N%D by the I Llhunntan Catholu* O Ra Ugi Ja Pro** Aoctt'u' 23.H So Ftakl*; A**

? MlOftEST 1. v£# 5721 COTTAGE ^-U1"1- CttlCAGd 57. 1LL. (JRATIS JUM D fc A U O A S t) H A tr O A S L^idSia Ueiuviy Katalike Iffta 1 » Tft. I ItliiumtaJt Daily Vtim4 f\ihli«n%d by the I llhunntan CatholU* O ra ugi Ja Pro** Aoctt'U' 23.H So ftakl*; A**. < Mo**., •. llllnoU 2231 Sn. Oaktry Are., CMcagn t. Kilnote T r teplione — \ Irglnla 7-A04O •41 N Telepttooo — Vlrfrinla 7-«4*0-4| Vienintelis tautinė* Ir tikybine* mlntl»s The tno«t lnflueatlal I.ithuanlan Daily h*imv%ų llenraitla pasaulyje THE LITHUANIAN DAILY, FRIEND tn America No. 232 Kaina 5 oeatal PIRMADIENIS, SPALIO (OCTOBER) 4, 1954 Priee 5 cente VOL. XXXVII • .-.. .. LONDONO KONFERENCIJOJE SUSITARTA i Formoza Peipingo žaidime Šį mėnesį rinksis dar keliose Indijos premjerą Nchru nepaprastai jaudina susišaudymai, vietose nutarimams tvarkyti kurie vyksta Quemoy — Amoy erdvėje tarp abiejų Kinijos vy riausybių karinių pajėgų. Nehru jaudinasi ne be pagrindo, nes jis, turbūt, goriausiai yra painformuotas apie Peipingo nuotai LONDON, spalio 4. — Devynių valstybių konferencija čia kas. baigėsi vakar pilnu susitarimu dėl V. Vokietijos apginklavimo, jai suverenumo grąžinimo ir jos įjungimo į Briuselio ir Atlanto Galop ir žinomi faktai nėra ~ '. ', raminą. Raudonoji Kinija ima Sią Savaitę SlltartlS paktus. telkti prieš Formozą karines Vakar susitarimai pasirašyti viena iš specialių JT organiza- ne kaip formalios sutartys, bet pajėgas (aviaciją ir parašiuti Triesto ginčui baigti . • . ,J... cijų, tačiau žinoma, kad jos yra kaip principų ir jų praktiško . :. ' ,J . ninkus), o JAV laivynas, dabar labai autonomiškosv , o atominės TRIESTE, sp. 4. — Po devy pritaikymo deklaracijos-proto- žymiai sustiprintas, plaukioja energijos organizacija tos auto nių mėnesių derybų Romoje, kolaj. -

Wayne Township Summer 2021

09/01/2021 Payment List Report FOR WAYNE TOWNSHIP Page: 1/40 11:04 AM All Records DB: Wayne Tax 2021 Special Population: Ad Valorem+Special Acts Summer Season, All parcels with or without payments Parcel No Name Tax Bill Payments Date 14-150-001-001-00 PASLEY DORTHA LIFE ESTATE 1,491.01 1,491.01 07/06/2021 14-150-001-002-02 MC DONALD LAND LLC 664.26 14-150-001-002-10 CLOUTIER BRADLEY 718.81 14-150-001-003-00 RANKIN DONALD D JR 87.65 14-150-001-004-00 MEAD AMANDA 849.98 849.98 08/23/2021 14-150-001-005-00 MURRAY LEON D & JANET L 818.30 818.30 07/19/2021 14-150-001-006-00 CARRINGTON DANIAL ET AL 294.65 14-150-001-007-00 BENSON DORTHA LIFE ESTATE 179.55 179.55 07/06/2021 14-150-001-008-00 PIKE LUMBER COMPANY INC 0.00 14-150-001-009-00 CERES FARMS LLC 72.84 14-150-001-010-00 HOUSENGER RICHARD 5.34 5.34 07/19/2021 14-150-001-011-00 EARL KENNETH D 99.79 14-150-001-012-00 PIKE LUMBER COMPANY INC 0.00 14-150-001-013-00 PIKE LUMBER COMPANY INC 0.00 14-150-001-014-00 FORD TODD B 374.24 14-150-001-015-00 MC DONALD LAND LLC 49.19 14-150-001-016-00 FORD TODD B 548.74 14-150-001-017-00 HOWELL DENNIS R ET AL 3.37 3.37 08/21/2021 14-150-001-018-00 KOVACS LANDON C 608.64 14-150-001-019-03 MIDDAUGH CHARLES A 716.42 14-150-001-019-11 PATZER BRAD & KAYLA 1,390.57 14-150-001-019-22 SPONSELLER HARRY & PHYLLIS 522.21 14-150-001-020-00 HOWELL DENNIS R ET AL 132.72 132.72 08/21/2021 14-150-001-021-00 HOWELL DENNIS R ET AL 215.10 215.10 08/21/2021 14-150-001-022-00 SCHROCK GRANT M & RHONDA K 958.42 958.42 07/27/2021 14-150-001-023-00 MC DONALD LAND LLC 201.09 14-150-001-024-00 -

Environmental Noise Management in Latvia

UNIVERSITY OF LATVIA FACULTY OF GEOGRAPHY AND EARTH SCIENCES Zanda Krūkle ENVIRONMENTAL NOISE MANAGEMENT IN LATVIA DOCTORAL THESIS Submitted for the scientific doctor's degree - doctor of science (Ph.D.) in earth sciences, physical geography, environmental sciences Scientific advisor: Assist. Prof., Dr. phys. Rūta Bendere Rīga, 2020 1 The doctoral thesis was carried out in the Department of Environmental Science, Faculty of Geography and Earth Sciences over the period from 2010 to 2020. Scientific advisor: Dr. phys., Assist. Prof. Rūta Bendere, University of Latvia Reviewers: Dr. geogr., Assoc. Prof. Iveta Šteinberga, University of Latvia Dr. sc. ing., Prof. Ritvars Sudārs, Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies Dr. techn., Prof. Linas Kliučininkas, Kaunas University of Technology Doctoral Committee: Dr. biol., Prof. Viesturs Melecis, University of Latvia, chairman of the Committee Dr. geogr., Prof. Oļģerts Nikodemus, University of Latvia Dr. habil. chem., Prof. Māris Kļaviņš, University of Latvia Dr. geogr., Assoc. Prof. Iveta Šteinberga, University of Latvia Dr. habil. paed., Prof. Raimonds Ernšteins, University of Latvia Dr. sc. ing., Prof. Gatis Bažbauers, Rīga Technical university Dr. geog., Assist. Prof. Oskars Purmalis, University of Latvia, secretary of the Committee The defence of the doctoral thesis will be held on the 12th of June, 2020 at 12:00 in a public session of the Doctoral Committee at the Faculty of Geography and Earth Sciences of the University of Latvia, 1 Jelgavas iela, Rīga. The dissertation is available at the Scientific Library of the University of Latvia, 4 Kalpaka blvd. References should be addressed to Dr. biol. Viesturs Melecis, University of Latvia, Faculty of Geography and Earth Sciences, 19 Raiņa blvd, LV-1586, Rīga. -

LITHUANIA NAME № YEAR Adomynas, Antanas & Ona; D

Righteous Among the Nations Honored by Yad Vashem by 1 January 2020 LITHUANIA NAME № YEAR Adomynas, Antanas & Ona; d. Natalija 7685 1997 Alekna, Povilas & Paulina 12424.2 2012 Aleknaviciene, Sofija & dght. Brone 10844.1 2006 Aleksandraviciene, Paulina 1858 1980 Andraitis, Antanas 5939 1994 Andriuskevicius, Petras & Joana 12229 2011 Anevicius, Jeronimas & Antanina, son Vytautas 11551 2009 Aneviciute, Juze 11551.1 2009 Antanaitis, Vincas & ch. Jonas, Stase 1459 1979 Anuzis, Ceslovas & Elena 9026.1 2000 Anuzis, Ignas & Elena 9026 2000 Arlauskas, Kazimieras & Veronika 11487 2009 Audejus, Juozas & Ona 601 1970 Augustinowicz, Ona & Juozas 7859.1 1998 Babarskis, Alfonsas & Jadviga 8832 2000 Babonas, Antanas 12002 2011 Bagdonavicius, Pranas 5215.1 1992 Bagurskas, Juozas & Marijona 13907 2019 Bajorinas, Pranas 2110.2 1982 Baksas Kazys & Maryte 10459 2004 Balcikonis, Antanas & Agota 6403 1994 Balcinas, Jonas & Barbora; sisters: Stefania & 6796 1995 Petronela Balciunas, Adomas & Anela 5956 1994 Baliutis, Adolfas & Ona 12718.2 2013 Balkene, Nina; sister Lidia Petrauskene 6114 1994 Baltutis, Vytas 1873 1980 Balutis, Juozas 12718.1 2013 Bartkevicius, Juozas & Stasia 1801 1980 Baublys, Dr. Petras 1183 1977 Baublys, Sergejus & Jadvyga 1183.1 1977 Beinaraviciai, Ursule 5446 1992 Beinaravicius, Vladas 5446 1998 Beinaris, Pranas & Kotryna 13607 2018 Beleckiene, Morta 9071.3 2000 Belskiene, Ona 7988 1998 Berciunas, Jurgis; sister Birute 7377 1996 Bernikiene, Petre 7029.1 1996 Bernotaite, Julija 11170 2007 Bielskis Aleksandras & Zose 10454 2004 Bila, Vincas -

800M Freestyle Women Results RANK SURNAME & NAME FED BORN 50 M 100 M 200 M 300 M 400 M 500 M 600 M 700 M FINAL TEAM CAT

SWIMMING 12 - 18 August 2019 Results Book 18th FINA World Masters Championships Gwangju 2019 800m Freestyle Women Results RANK SURNAME & NAME FED BORN 50 m 100 m 200 m 300 m 400 m 500 m 600 m 700 m FINAL TEAM CAT AGE GROUP 85-89 QUALIFYING STANDARD: 28:50.00 CR : 16:45.59 WR : 14:27.71 1 DICKEY Dorothy AUS 1930 55.83 2:02.63 4:23.46 6:45.77 9:09.74 11:33.06 13:58.29 16:23.71 18:44.88 DONCASTER DOLPHINS 85-89 1:06.80 2:20.83 2:22.31 2:23.97 2:23.32 2:25.23 2:25.42 2 BUSCH HERRERA Eliana Bea CHI 1934 58.48 2:09.13 4:36.35 7:06.30 9:34.30 12:03.46 14:33.43 17:02.59 19:20.38 Club Delfines de Las Condes 85-89 1:10.65 2:27.22 2:29.95 2:28.00 2:29.16 2:29.97 2:29.16 AGE GROUP 80-84 QUALIFYING STANDARD: 25:50.00 CR : 14:29.77 WR : 13:51.21 1 ROBERTSON Denise AUS 1935 51.80 1:48.75 3:42.92 5:39.02 7:34.93 9:31.52 11:28.03 13:23.06 15:15.20 MIAMI MASTERS SWIMMING CLUB INC 80-84 56.95 1:54.17 1:56.10 1:55.91 1:56.59 1:56.51 1:55.03 2 REICH Helga GER 1936 49.22 1:47.44 3:46.07 5:43.92 7:42.12 9:43.75 11:45.24 13:47.52 15:47.72 SC Wiking Herne 1921 80-84 58.22 1:58.63 1:57.85 1:58.20 2:01.63 2:01.49 2:02.28 3 PETRI Gisela GER 1937 1:03.35 2:12.25 4:38.29 7:07.52 9:33.67 12:02.09 14:32.58 17:01.78 19:27.96 Mainzer SV 01 80-84 1:08.90 2:26.04 2:29.23 2:26.15 2:28.42 2:30.49 2:29.20 4 MARUYAMA Fusae JPN 1938 1:09.31 2:25.24 4:54.91 7:31.81 10:04.35 12:40.94 15:17.53 17:56.96 20:33.59 MAINICHI MSC 80-84 1:15.93 2:29.67 2:36.90 2:32.54 2:36.59 2:36.59 2:39.43 AGE GROUP 75-79 QUALIFYING STANDARD: 23:55.00 CR : 13:00.65 WR : 12:58.94 1 KETELSEN Elisabeth -

GI Case Analysis Coastal Areas

TASK 4.1: IN-DEPTH CASE ANALYSIS – GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE IMPLEMENTATION AND EFFICIENCY – ENV.B.2./SER/2010/0059 PROJECT TEAM: IEEP, ECOLOGIC, GHK, SYZYGY, TAU, UNIVERSITY OF ANTWERP, VITO GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE IN-DEPTH CASE ANALYSIS THEME 3: MULTIFUNCTIONAL USE OF COASTAL AREAS Author: Marcelline Bonneau (GHK), [email protected], +32 2 2750123 1 Introduction The coast is the area where the land meets the sea and more particularly the “air-sea-land interface zone around continents and islands” (Firn Crichton Roberts Ltd and University of Strathclyde 2000). As such, it has a total length of 89,000 km in the EU. In addition, half the population of the Member States which have a coastline live within 50 km of the sea (European Commission, 2000). Coasts are defined by their richness in biodiversity elements (see,for example, European Environment Agency, 2002, and the INTERREG IIIC Deduce project). In particular, eight out of the 40 EU-listed priority habitats of wild fauna and flora fall into the coastal habitat. Also, a third of the EU's wetlands are located on the coast as well as more than 30% of the Special Protected Areas designated under the Birds Directive (79/409/EEC). In addition, the reproduction and nursery grounds of most fish and shellfish species of economic value also lie in coastal areas and account for almost half of the jobs in the fisheries sector (European Commission, 1997). At the same time, coasts play an important role in the development of local and regional economies. A study carried out by the University of the Aegean (2001), showed that the most important sectors in economic terms in the coastal zones were mostly tourism and leisure, agriculture and food, sea fisheries, ports and shipping, and residential housing. -

LITHUANIA at the CROSSROADS " - Edited by A

LITHUANIA AT THE CROSSROADS " - Edited by A. P. TASKUNAS and J. W. DOYLE LITHUANIA was the first republic LITHUANIA AT THE CROSSROADS to break away from the giant Soviet Union. On March 11, 1990, the newly elected Lithua nian Parliament restored the country's independence, and started off on the thorny road to freedom. Many in the West believed that the new Lithuania - with 31/z million people living in the same land area as Tasmania - would not be able to survive econo mically. But Lithuania has. By now, virtually all Western coun tries have recognised Lithuania as an independent state. This book offers an excellent insight into present-day Lithuania: a fascinating country about which insufficient is known. A panel of experts from the University of Tasmania discuss the legal, economic and environ mental challenges facing Lithuania now. There are also poems, a historical essay and a glimpse at the Lithuanian folk-art. Recommended Retail Price $7.50. ISSN 1031-3958 LITHUANIAN PAPERS • VOLUME 4 LITHUANIAAT THE CROSSROADS Selected Readings Edited by Algimantas P. TASKUNAS and John W. DOYLE Sandy Bay, Tasmania: T.U.U. Lithuanian Studies Society 1991 This book is Volume 4 (1990)n in the annual series, LITHUANIAN PAPERS published by the Tasmania Uiversity Union Lithuanian Studies Society, PO Box 777, Sandy Bay, Tasmania 7005, Australia. © 1991 by TUU Lithuanian Studies Society, Sandy Bay, Tasmania. All rights reserved, No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. -

The Soviet Counterinsurgency in the Western Borderlands Alexander Statiev Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76833-7 - The Soviet Counterinsurgency in the Western Borderlands Alexander Statiev Index More information Index Abakumov, Viktor, 247 Civil War, 24–25 Abwehr, 47–48, 56, 105 credibility, 204–207 Acción Democrática, 328 effectiveness as a counterinsurgency agrarian policies method, 195–196, 200–202 Agrarian Law of 1944, 144, 150, 151 German collaborators, 197–198 antihomestead campaign, 154–155 in 1941, 196 as a populist measure, 142, 144, 146, motivations, 196–198 161–162 scale, 198, 202 as motivation for resistance, 104, 161–163 Anders, Wladyslaw, 91 collectivization, 1929–33, 28 Andrusiak, Vasyl’, 237 collectivization, 1940–41, 41, 142–143 Antonov-Ovseenko, Vladimir, 18 collectivization, 1947–49, 157–161 Arajs, Viktors, 70 Decree on Land, 15, 24, 33, 141, 146 Arsenych, Mykola, 108, 238 persecution of kulaks, 28, 147–153, Atlantic Charter, 89 177–179 Audrini, 71 persecution of seredniaks, 153 Autocephalous Orthodox Church, Poland, reforms of 1939–40, 140–144 42, 43 reforms of 1944, 144–146, 156–157 Autocephalous Orthodox Church, Ukraine, resentment toward collectivization, 65–66, 84, 271 142–143, 158–159, 162–163 collaboration with Germany, 72, 73 strategy in the borderlands, 139–140 demise, 263 taxation, 143, 149–151, 155 Autonomous Orthodox Church, Ukraine, 66, Aizsargi, 39, 70, 76, 185, 276 84, 257, 263 AK (Armija Krajowa) Bataliony Chlopskie, 92 Bach-Zelewski, Erich von dem, 318, 331 cooperation with the Red Army, 118–119 Backe, Herbert, 63 ethnic violence, 87 Baltic region ideology, 49 agrarian