American Corporate Governance Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Structures in Australia

Business Structures in Australia 1. Introduction This paper presents an overview of the various types of business structures available in Australia – each of which necessarily attracts different legal and taxation consequences. 2. Sole Trader When a person conducts business as an individual, he or she is a sole trader. From a legal point of view there is no difference between the person and the business. As such, the liabilities of the business are the liabilities of the individual – he or she is personally liable for any and all business-related obligations, such as debts resulting from the purchase of goods or services or from court judgments and for the performance of warranty obligations in respect of goods supplied or work performed. It is possible for a sole trader to carry on business under a name other than his or her own name. In that case, the name must be registered as a business name. Until 30 June 2011, that will have to be done under the business names legislation in each of the state(s) and/or territory(ies) where the business is conducted. As from 1 July 2011, a notional business name registration system, administered by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), will be introduced. 3. Partnerships A partnership is where two or more individuals, corporate or other entities, agree to carry on business together with a view to profit. All partners in the partnership must have the same goals, and, so far as third parties are concerned, each partner is equally responsible for decisions made by the other partner or partners on behalf of the business. -

Australia Introduction

GLOBAL PRACTICEINTRODUCTION GUIDE AUSTRALIA Definitive global law guides offering comparative analysis from top ranked lawyers ContributingLAW AND PRACTICE: Editor p.p.2 ElizabethDaleContributed Cendali by Morony HerbertKingZhong & Lun Spalding Smith Law Freehills Firm CliffordKirklandThe ‘Law &Chance& EllisPractice’ LLPLLP sections provide easily accessible information Shareholders’on navigating the legal systemRights when conducting business & in the jurisdiction. Leading lawyers explain local law and practice at key Shareholdertransactional stages andActivism for crucial aspects of doing business. TRENDS AND DEVELOPMENTS: p.<?> Contributed by Hogan Lovells (CIS) The ‘Trends & Developments’ sections give an overview of current trends and developments in local legal markets. Leading lawyers analyse Australia particular trends or provide a broader discussion of key developments Herbert Smith Freehills in the jurisdiction. chambers.com INTRODUCTION LAW AND PRActice Law and Practice Contributed by Herbert Smith Freehills Contents 1. Shareholders’ Rights p.3 2. Shareholder Activism p.8 1.1 Types of Company p.3 2.1 Legal and Regulatory Provisions p.8 1.2 Type or Class of Shares p.4 2.2 Level of Shareholder Activism p.9 1.3 Primary Sources of Law and Regulation p.4 2.3 Shareholder Activist Strategies p.10 1.4 Main Shareholders’ Rights p.5 2.4 Targeted Industries / Sectors / Sizes of 1.5 Shareholders’ Agreements / Joint Venture Companies p.10 Agreements p.5 2.5 Most Active Shareholder Groups p.11 1.6 Rights Dependent Upon Percentage of Shares p.5 2.6 Proportion of Activist Demands Met in Full / 1.7 Access to Documents and Information p.5 Part p.11 1.8 Shareholder Approval p.6 2.7 Company Response to Activist Shareholders p.11 1.9 Calling Shareholders’ Meetings p.6 3. -

Doing Business in Australia Has Been Prepared for the DOING BUSINESS Use of Businesses Exploring the Opportunities of Establishing a Presence in Australia

ABSTRACT Doing Business in Australia has been prepared for the DOING BUSINESS use of businesses exploring the opportunities of establishing a presence in Australia. Given the ever-changing business landscape this document has been prepared as a guide and we IN AUSTRALIA recommend professional advice should be sought. Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................ 0 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Business structures ............................................................................................................................. 5 Tax Implications of Structures ......................................................................................................... 7 Sole Trader/ Sole Proprietorship ..................................................................................................... 7 Partnership ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Company .......................................................................................................................................... 8 Trust ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Accounting, Reporting and Audit requirements -

Limited Liability (S 9, 112) Limited by Shares (Public Or Proprietary)

TOPIC 1: INTRODUCTION – Types of Companies ‘Companies’ formed by registration under the Corporations Act as either public or proprietary companies; s 9 A company is EITHER a proprietary or a public company Proprietary (Pty Ltd) Public (Ltd) Shareholders Minimum 1 shareholder Minimum 1 shareholder s 45A(1); s 113 Maximum 50 non-employee No maximum shareholder Members Minimum 1 member Minimum 1 member s 114 No maximum Directors Minimum 1 director (resident) Minimum 3 directors (2 resident) + s 201A 1 company secretary Finance Cannot obtain funds from the public Can obtain funds from public s 45A(1); s 113 (w/disclosure document) Listing Cannot be listed Can be listed or unlisted s 45A(1); s 113 BUT not all public companies can be listed on the stock exchange (ASX) Type Limited by shares Limited by shares s 45A(1); s 112 Unlimited with share capital Limited by Guarantee Unlimited with share capital No Liability Company Registration ASIC Unlisted – ASIC, APRA Listed – ASIC, ASX, APRA • A public company, which adopts a constitution MUST lodge a copy with ASIC together with a copy of any special resolutions altering its provisions (ss 117(3), 136(5)). It is then publicly available. • A proprietary company, which adopts a constitution, need not lodge with ASIC but must send a copy to a member of the company upon request (s 139) Liability Limited Liability Unlimited Liability (s 9, 112) (s 9, 112) Limited by Shares Unlimited Limited by Guarantee No Liability (Public or proprietary) (Public or proprietary) (Public Companies) (Only public mining e.g. commercial e.g. -

Allianz Group SFCR 2016 Solvency an Condition R Allianz Group SFCR

Allianz Group SFCR 2016 Solvency and Financial Condition Report CONTENT Executive Summary 3 A Business and Performance 5 A.1 Business _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 7 A.2 Underwriting Performance __________________________________________________________________________________________________ 10 A.3 Investment Performance ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ 16 A.4 Performance of Other Activities ______________________________________________________________________________________________ 18 A.5 Any Other Information _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 19 B System of Governance 20 B.1 General Information on the System of Governance ________________________________________________________________________________ 23 B.2 Fit and Proper Requirements_________________________________________________________________________________________________ 37 B.3 Risk Management System including the Own Risk and Solvency Assessment ____________________________________________________________ 38 B.4 Internal Control System ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 45 B.5 Internal Audit Function _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 46 B.6 Actuarial Function _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

(2) Business Structures.Pdf

CA BUSINESS SCHOOL EXECUTIVE DIPLOMA IN BUSINESS AND ACCOUNTING SEMESTER 1: Preparation of Financial Statements Business Structures M B G Wimalarathna (ACA, ACMA, ACIM, SAT, ACPM)(MBA–PIM/USJ) Introduction As we discussed in chapter 01, every entity must identify & record business transactions for the given period and importantly such transaction (which are identified and recorded) should belongs to the given entity. An entity refers collection (pool) of interrelated group of people acting towards achieving common goal(s) and will be either one of the following; Sole Trader Partnership Company Non-profit motive organization Trust Period should be either a calendar year or an assessment year for local company. Sole Trader/Sole Proprietorship A Sole trader is a business owned by a person/an individual and control/manage by himself. Key features: Owner & controller is a same individual. Not a legal entity. Formation is not complex. Need to obtain BRN & TIN. For tax purpose, entity’s income is treated as individual’s income (owner) Advantages Disadvantages - Easy & inexpensive to form. - Unlimited liability since not - Not govern under strict rules & treated as separate legal entity. regulations. - Limited skills & capabilities. - Total autonomy over business - Cease the business when owner decisions. experience incapability. - Enjoy entire benefits. - Bear entire loss and liabilities. - Not charge tax on business profit. Partnership A Partnership is an association of two or more persons or entities that carry on business as partners with the common motive of earning profit. (how partnership differs from JV) A partnership could be form verbally, impliedly or in writing. Most of the partnerships carry on business in line with the provisions made in Partnership Agreement. -

19RU-004 When Large Becomes Small

When large becomes small Reporting Update 23 April 2019, 19RU-004 Highlights • Change to Corporations Regulations • Impact of change in thresholds • Practical considerations • KPMG comment Change to Corporations Regulations On 16 November 2018 the government released a public consultation Exposure Draft Corporations Amendments (Proprietary Company Thresholds) Regulations 2018. After stakeholder comment the government registered the Corporations Amendments (Proprietary Company Thresholds) Regulations 2019. Registration occurred on 5 April 2019. No changes have been made to the Regulations, as exposed, following the consultation process. The new regulation doubles the thresholds for determining whether a company is Small/large thresholds a large or small proprietary company for a financial year. A proprietary company is doubled large if it meets two of the three thresholds at the end of its financial year. Otherwise it is small. The table below outlines the three thresholds. Threshold Current From 1 July 2019 Consolidated revenue $25 million $50 million for the financial year * or more or more Consolidated gross assets at the end of $12.5 million $25 million the financial year * or more or more Employees^ of the company and the 50 FTE employees 100 FTE employees entities it controls or more or more *For the company and any controlled entities ^Part-time employees are counted as an appropriate fraction of the full-time equivalent (FTE) Under the Corporations Act 2001 (Corps Act), large proprietary companies are required to lodge an annual financial report, a director’s report and an auditor’s report with ASIC. Small proprietary companies have no such requirement to lodge (unless directed to by ASIC or directed by 5% or more of their shareholders) and are generally required to keep sufficient financial records. -

About Companies CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1 About Companies Introduction ¶1-001 What is a company? ¶1-050 Companies as a Form of Business Organisation Introduction ¶1-100 What are companies like? ¶1-120 What are listed companies, and who invests in them? ¶1-140 The Architecture of Companies Introduction ¶1-200 How is a company’s capital structured? ¶1-220 How is a company’s management structured? ¶1-240 What are a company’s key legal attributes? ¶1-260 The Historical Development of Companies How did companies develop? ¶1-300 What are corporations aggregate and joint stock, and when did these concepts develop? ¶1-320 When did the right to incorporate companies become generally available? ¶1-340 When was limited liability first introduced? ¶1-360 When were companies first used for small business? ¶1-380 Some Key Terms What do these terms mean? ¶1-500 Oxford University Press Sample Only Hanny 4pp.indb 3 11/26/2018 3:29:24 AM 4 About Companies [¶1-001] Introduction This book is about company law and how it works to create companies, to organise the relationships between participants in companies (including the directors and other corporate officers, and the company’s members), to facilitate the raising of capital by companies to carry on their activities, and to give legal effect to dealings between companies and others, such as their creditors and the people with whom they contract. Companies are the most significant form of business organisation in Australia and in most other developed economies. This Chapter introduces some of the basic features of companies. The first part looks at companies as a form of business association and explains the difference between public listed companies and unlisted (often privately owned) companies. -

Establishing a Business Entity in India

Fall 08 Fall 15 INTERNATIONAL LAWYERS NETWORK ESTABLISHING A BUSINESS ENTITY: AN INTERNATIONAL GUIDE ILN CORPORATE GROUP [ESTABLISHING A BUSINESS ENTITY] 2 This guide offers an overview of legal aspects of establishing an entity and conducting business in the requisite jurisdictions. It is meant as an introduction to these market places and does not offer specific legal advice. This information is not intended to create, and receipt of it does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship, or its equivalent in the requisite jurisdiction. Neither the International Lawyers Network or its employees, nor any of the contributing law firms or their partners or employees accepts any liability for anything contained in this guide or to any reader who relies on its content. Before concrete actions or decisions are taken, the reader should seek specific legal advice. The contributing member firms of the International Lawyers Network can advise in relation to questions regarding this guide in their respective jurisdictions and look forward to assisting. Please do not, however, share any confidential information with a member firm without first contacting that firm. This guide describes the law in force in the requisite jurisdictions at the dates of preparation. This may be some time ago and the reader should bear in mind that statutes, regulations and rules are subject to change. No duty to update information is assumed by the ILN, its member firms, or the authors of this guide. The information in this guide may be considered legal advertising. Each contributing law firm is the owner of the copyright in its contribution. All rights reserved. -

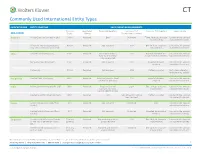

Commonly Used International Entity Types

Commonly Used International Entity Types COUNTRY/REGION ENTITY STRUCTURE BASIC FORMATION REQUIREMENTS Minimum Registered Corporate Secretary Minimum # of Minimum # of Directors Legal Liability ASIA-PACIFIC Capital Address Shareholders/Partners Australia Public Company (Limited or Ltd.) AUD 0 Required One Unlimited Three. At least 2 must be Limited to the amount local residents subscribed for shares Private or Proprietary Company AUD 0 Required Not required 1-50 One. At least 1 must be Limited to the amount (Pty. Ltd. or Proprietary Limited) local resident subscribed for shares China Limited Liability Company CNY 0 Required Not required. But a 1-50 Board of directors or a Limited to the amount local representative single executive director subscribed for shares may be required. Company Limited by Shares CNY 0 Required Not required 2-200 Board of directors Limited to the amount required subscribed for shares Partnership CNY 0 Required Not required 2-50 Partner managed Not a separate legal entity from its parent Hong Kong Limited Private Company HKD 0 Required Required, must be local 1-50 Board of directors Limited to the amount resident or company required subscribed for shares India Private Limited Company (Pvt Ltd) INR 0 Required Required if initial 2-200 Two. At least 1 must be Limited to the amount capital investment local resident subscribed for shares exceeds INR100 million Limited Liability Partnership (LLP) INR 0 Required N/A Two. At least 1 must be Partner managed Limited to the amount local resident subscribed for shares Japan General Corporation (Kabushiki JPY 1 Required Not required Unlimited One Limited to the amount Kaisha) subscribed for shares Limited Liability Company (Godo- JPY 1 Required Not required Unlimited Managed by managing Limited to the amount Kaisha) members subscribed for shares Singapore Private Limited Company (Private $1 in any Required Required and must be 1-50 One. -

Example Public Company Limited. Guide to Annual Reports

AUDIT Example Public Company Limited Guide to annual reports – illustrative disclosures 2015-16 November 2015 kpmg.com.au b | Example Public Company Limited – illustrative disclosures Concise, clear and informative financial reporting As evidenced in our publication A new era in corporate reporting, public companies in Australia continue to challenge themselves to prepare more relevant and user friendly financial reports. 2015 has seen a marked increase in companies de-cluttering their financial reports by reducing immaterial or irrelevant disclosures, reordering notes into more logical groupings and rewriting technical wording into plain English. With few new or amended standards or regulatory requirements to apply this year, now is the time to consider whether you too are reporting your financial information in the most meaningful way. This publication provides a large range of illustrative disclosures, for the most part without regard to materiality. We encourage you to be careful not to become buried in compliance to the detriment of relevance. Our Example Public Financial Statements website is designed to support you in this goal, providing access to our guidance and tools to assist you in the preparation of your annual report. As in recent years, due to Australia’s close alignment to IFRS, we have made minimal changes to the source document prepared by our international colleagues and built the Australian-specific disclosures around this guide. In addition, the publication covers both 31 December 2015 and 30 June 2016 annual financial year ends. The navigation bookmarks and links in our digital publication will assist you to identify the changes and disclosures you need in a quick and accessible manner. -

Applying Ria to Policy Making in the Area of Corporate Governance

APPLYING RIA TO POLICY MAKING IN THE AREA OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE This is a chapter taken from the publication Regulatory Impact Analysis: A Tool for Policy Coherence, published in September 2009. For more details of the complete publication, please use the following link: http://www.oecd.org/document/47/0,3343,en_2649_34141_43705007_1_1_1_1,00.html Corporate Affairs Division, Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2, rue André-Pascal, Paris 75116, France www.oecd.org/daf/corporateaffairs CHAPTER 5. APPLYING RIA TO POLICY MAKING IN THE AREA OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Chapter 5 looks at a study within the OECD of the application of RIA in the field of the regulation of corporate governance. Noting that the requirement to undertake RIA is an established part of the regulatory systems of OECD members, this chapter examines examples of the application of RIA by financial services regulators to strengthen their evidence-based policy-making. It draws on examples from OECD experience notably; Canada, Australia, the UK, US and the EU. It looks at how regulators have dealt with some of the challenges to effective RIA which include; defining the problem, undertaking effective consultation, and identifying and measuring costs and benefits. Introduction The general requirement to undertake Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) on new policy initiatives is becoming more commonplace in OECD jurisdictions. This development has been aided by the 2005 OECD Guiding Principles for Regulatory Quality and Performance (OECD, 2005) which promoted the use of RIA to assess impacts and review regulations systematically to ensure that they meet their objectives efficiently and effectively.