TEXAS PUBLIC POLICY FOUNDATION Restorative Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Legislative Hearing 2 on 3 4 June 26, 2003 5

Redistricting Subcommittee Hearing in Lubbock Witness: - June 26, 2003 Page 1 1 LEGISLATIVE HEARING 2 ON 3 4 JUNE 26, 2003 5 ----------------------------------------------------------- 6 A P P E A R A N C E S 7 REPRESENTATIVE CARL ISETT 8 REPRESENTATIVE KENNY MARCHANT 9 REPRESENTATIVE KENT GRUSENDORF 10 ----------------------------------------------------------- 11 LEGISLATIVE PUBLIC HEARING ON CONGRESSIONAL REDISTRICTING PLAN TAKEN BEFORE LINDI REEVES, CERTIFIED 12 SHORTHAND REPORTER AND NOTARY PUBLIC IN AND FOR THE STATE OF TEXAS, AT 9:00 A.M., ON THE 26TH DAY OF JUNE, 2003. 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Hoffman Reporting & Video Service www.hoffmanreporting.com Redistricting Subcommittee Hearing in Lubbock Witness: - June 26, 2003 Page 2 1 REPRESENTATIVE MARCHANT: WHILE WE'RE 2 BEGINNING TO START THIS MORNING, LET ME GIVE YOU A LITTLE 3 INFORMATION. OUT ON THE FRONT DESK ARE SOME MAPS. WHAT IS 4 OUT FRONT ARE TWO MAPS. ONE OF THEM IS A MAP OF THE 5 CURRENT DISTRICTS AS THEY ARE NOW, AS ORDERED BY THE COURT, 6 AND THEN THERE IS ANOTHER MAP WHICH IS THE MAP THAT WAS 7 VOTED OUT OF THE HOUSE, THE REDISTRICTING COMMITTEE BACK IN 8 THE REGULAR SESSION. THOSE ARE THE TWO MAPS WE FEEL LIKE 9 ARE THE MOST IMPORTANT MAPS TO BE BROUGHT TODAY. 10 THERE ARE MANY, MANY MORE MAPS AVAILABLE ON THE 11 REDISTRICTING ON THE INTERNET, AND MANY OF YOU -- IF YOU 12 ARE INTERESTED IN THAT INFORMATION THE CLERKS WILL BE ABLE 13 TO TELL YOU, AND IT'S OUT FRONT, INFORMATION ON HOW TO GET 14 ON THE INTERNET AND GET INTO THOSE PROGRAMS, IT'S OUT AT 15 THE FRONT DESK. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 150 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, APRIL 1, 2004 No. 44—Part II House of Representatives TRANSPORTATION EQUITY ACT: A Mr. Chairman, I reserve the balance want to change the policy with this LEGACY FOR USERS—Continued of my time. new legislation. So this was not to b 1545 Mr. YOUNG of Alaska. Mr. Chair- side-step the courts but, rather, to man, I yield myself such time as I may keep the law the same. Now, undoubtedly, supersized trucks consume. Mr. YOUNG of Alaska. Mr. Chair- mean growing safety risks for highway I will say, though, I am usually in man, reclaiming my time, but the in- drivers and pedestrians on narrow favor of what occurs by State action, dustry or the plaintiff that filed the roads. According to the U.S. Depart- but what this amendment does, it al- suit is now being precluded from going ment of Transportation, an estimated lows the State of New Jersey to limit forth. If my colleague wants to do that, 5,000 Americans die each year in acci- large trucks and twin-trailer combina- have the court or New Jersey file an in- dents involving large trucks, and an tion trucks to the interstate system, junction against the court’s decision. additional 130,000 drivers and pas- not intrastate, the New Jersey Turn- Do not ask us to undo what a court has sengers are injured. New Jersey has a pike and the Atlantic City Expressway, ruled. -

Texas Legislative Black Caucus 1108 Lavaca St, Suite 110-PMB 171, Austin, TX 78701-2172

Texas Legislative Black Caucus 1108 Lavaca St, Suite 110-PMB 171, Austin, TX 78701-2172 Chairman, About Us Sylvester Turner The Texas Legislative Black Caucus was formed in 1973 and consisted of eight members. These founding District 139- Houston members were: Anthony Hall, Mickey Leland, Senfronia Thompson, Craig Washington, Sam Hudson, Eddie 1st Vice Chair Bernice Johnson, Paul Ragsdale, and G.J. Sutton. The Texas Legislative Black Caucus is a 501(c)(3) non-profit, Ruth McClendon non-partisan organization composed of 15 members of the Texas House of Representatives committed to District 120- San Antonio addressing the issues African Americans face across the state of Texas. Rep. Sylvester Turner is Chairman of the Texas Legislative Black Caucus for the 81st Session. State Senators Rodney Ellis and Royce West, the two 2nd Vice Chair Marc Veasey members who comprise the Senate Legislative Black Caucus, are included in every Caucus initiative as well. District 95- Fort Worth African American Legislative Summit Secretary In April 2009, the Texas Legislative Black Caucus, in conjunction with Prairie View A&M University and Texas Helen Giddings Southern University, hosted the 10th African American Legislative Summit in Austin at the Texas Capitol. District 109- Dallas Themed “The Momentum of Change,” the 2009 summit examined issues that impact African American Treasurer communities in Texas on a grassroots level and provided a forum for information-sharing and dialogue. The next Alma Allen African American Legislative Summit is set for February 28th – March 1st, 2011. District 131- Houston Recent Initiatives Parliamentarian Joe Deshotel Institute for Critical Urban Policy and Department of African & African Diaspora Studies District 22- Beaumont Chairman Turner spearheaded an effort with The University of Texas at Austin to establish the Institute for Critical Urban Policy and Black Studies Department, which will both launch in the fall of General Counsel 2010. -

Undergraduate Medical Academy Confident Achievers Reaching Excellence

Undergraduate Medical Academy Confident Achievers Reaching Excellence Reaching Excellence UMA sophomore, Sumit Jha was recently acknowledged IN THIS ISSUE for his academic achievements and excellence at the 2013 Reaching Excellence…pg1 PVAMU Celebration of Excellence Award Ceremony hosted 2013 African American by the Roy G. Perry College of Engineering. This ceremony Legislative Summit…. Pg2 recognizes the top students and staff throughout the 2013 Red Ball Luncheon & Fashion Show……pg3-4 engineering department who have exceeded expectations. Sumit was among 35 students including fellow UMA Fuller Trail Ride……….pg4 student, senior, Gavannie Beharie. The guest speaker of the evening was Colonel Christopher Sallese of the US Army UPCOMING EVENTS Corps of Engineers. On behalf of the UMA staff and students we would like Midterms to congratulate Sumit on his accomplishments. Keep up the March 4-8 great work! Spring Break March 11-15 Tuskegee Pre-Vet Trip March 20-24 Financial Literacy & Graduate Prep March 23 @9am-4pm AMEC/ SMNA Conference March 27-31 UNT TCOM April 5-6 Texas A&M April 12 2013 African American Legislative Summit- Austin, Texas LEFT TO RIGHT UMA student posing outside of the Texas State Capitol Junior, Jasmine Guidry with U.S. Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee UMA students with Wilhelmina Delco UMA students with Dennis Daniels, Dr. George C. Wright, U.S. Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee, Rep. Ruth McClendon, Dr. Thomas- Smith, & Rep Sylvester Turner Ceiling of the Texas State Capitol 2013 Red Ball Luncheon & Fashion Show – Flemings Steak House LEFT TO RIGHT Dr. & Mrs. Daniels with mistress of ceremony, Lily Jang Former UMA student, Renny Varghese, UMA staff member Kathleen Straker and guest UMA senior & Red Ball model Jordan Etters UMA juniors & Red Ball models Auja Smith and Lynh Ly. -

TJJD Today, January

Texas Juvenile Justice A PUBLICATION OF THE today TEXAS JUVENILE JUSTICE DEPARTMENT A Message From the Director El Paso County Takes To The Big Stage page 2 January has been busy at TJJD as we TJJD Implements Human Trafficking Course for All continue to move rapidly on a number Direct Care Staff in February page 3 of initiatives. On January 13, we again met with the Regionalization Task Force SPOTLIGHT: Vikki Reasor, Principal, Gainesville State as we move toward implementation this School page 4 a funding application for the regional TJJD Co-Hosts Strengthening Youth & Families diversionsummer. ofAt individualthis meeting, youth. we finalizedWe also Conference page 5 discussed the work being done within each David Reilly Judy Davis Honored as 2015 Outstanding Community region to identify regionalization opportunities. A number of Volunteer page 7 private providers shared details of how their services could be incorporated into the regionalization efforts. It was a productive Rep. Ruth McClendon Honored as 2015 Champion for meeting. I am particularly grateful to Travis County for hosting. Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention page 7 Our county partners are doing a great job of working within their regions to ensure services are available when we begin our Family Involvement Survey Demonstrates Agency diversion efforts in June. Gains page 8 We are continuing to look for avenues to expand our canine AMIKids-Rio Grande Valley: TJJD’s Residential Provider program – Pairing Achievement With Success (PAWS) – into of the Year! page 9 additional facilities. Last November, the PAWS program at our Harris County Juvenile Probation Department and Ron Jackson facility in Brownwood teamed with Service Dogs Disability Rights, Texas Form Partnership page 9 Inc., an organization that trains dogs to assist Texans living with hearing or mobility challenges. -

The Texas A&M University System, Meeting of the Board of Regents

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY SYSTEM HELD IN COLLEGE STATION, TEXAS December 5-6, 2002 (Approved January 23, 2003, Minute Order 33-2003) TABLE OF CONTENTS MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS December 5-6, 2002 CONVENE BOARD MEETING – THURSDAY, DECEMBER 5.................................................................................1 CHAIRMAN’S REMARKS..............................................................................................................................................1 INVOCATION ..................................................................................................................................................................2 CHANCELLOR’S REMARKS.........................................................................................................................................2 OTHER ITEMS .................................................................................................................................................................3 MINUTE ORDER 229-2002 (AGENDA ITEM 25) DESIGNATION OF THE REGENTS PROFESSOR SERVICE AWARDS AND THE REGENTS FELLOW SERVICE AWARDS FOR 2001-2002, THE TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY SYSTEM ................3 RECESS..............................................................................................................................................................................4 RECONVENE AND SPECIAL PRESENTATION........................................................................................................4 -

NBAF Final Environmental Impact Statement

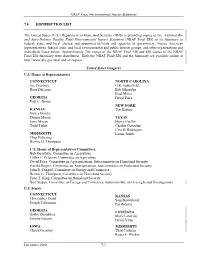

NBAF Final Environmental Impact Statement 7.0 DISTRIBUTION LIST The United States (U.S.) Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is providing copies of the National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility Final Environmental Impact Statement (NBAF Final EIS) or its Summary to federal, state, and local elected and appointed officials and agencies of government; Native American representatives; federal, state, and local environmental and public interest groups; and other organizations and individuals listed below. Approximately 700 copies of the NBAF Final EIS and 850 copies of the NBAF Final EIS Summary were distributed. Both the NBAF Final EIS and the Summary are available online at http://www.dhs.gov/nbaf and on request. United States Congress U.S. House of Representatives CONNECTICUT NORTH CAROLINA Joe Courtney G.K. Butterfield Rosa DeLauro Bob Etheridge Brad Miller GEORGIA David Price Paul C. Broun NEW YORK KANSAS Tim Bishop Nancy Boyda Dennis Moore TEXAS Jerry Moran Henry Cuellar Todd Tiahrt Charles Gonzalez Ciro D. Rodriguez MISSISSIPPI Lamar Smith Chip Pickering Bennie G. Thompson U.S. House of Representatives Committees Bob Goodlatte, Committee on Agriculture Collin C. Peterson, Committee on Agriculture David Price, Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Homeland Security Harold Rogers, Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Homeland Security John D. Dingell, Committee on Energy and Commerce Bennie G. Thompson, Committee on Homeland Security Peter T. King, Committee on Homeland Security Bart Stupak, Committee on Energy and Commerce, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations U.S. Senate CONNECTICUT KANSAS Christopher Dodd Sam Brownback Joseph Lieberman Pat Roberts GEORGIA LOUISANA Saxby Chambliss Mary Landrieu Johnny Isakson David Vitter IOWA MISSISSIPPI Chuck Grassley Thad Cochran Roger F. -

Congressional Record—House H2042

H2042 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE April 1, 2004 COMMEMORATING WOMEN’S find our rightful place in this body and Or let us take another signature HISTORY MONTH in our country. issue: the Violence Against Women The SPEAKER pro tempore. Under b 1845 Act. These programs are cut for next the Speaker’s announced policy of Jan- year $22 million over what was in the We certainly do not suffer, as many budget for this year. uary 7, 2003, the gentlewoman from the of our sisters do around the world. For District of Columbia (Ms. NORTON) is Mr. Speaker, I can only hope that example, in Kuwait, one of our allies, these programs that I am going to go recognized for 60 minutes as the des- women cannot even stand for election ignee of the minority leader. through get the attention of the Con- to any office. gress and the appropriators and that Ms. NORTON. Mr. Speaker, as March Mr. Speaker, I was a Member of the they come to their senses and put some slips away, a number of women in the House when the so-called ‘‘Year of the House did not want to let the year go of this money back. Woman’’ was informally proclaimed. Republicans have been grandstanding by without commemorating Women’s That was the year when the confirma- History Month. We recognize this is about an important issue that concerns tion of Justice Clarence Thomas all of us. I say ‘‘grandstanding’’ be- April 1. This is no April fool’s joke. brought women forward, given the con- cause the way to indicate that it mat- Women are a very serious concern of troversy surrounding his nomination, ters to you is, of course, to put just a the women who will come forward this that a man who had been accused of little money in it. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E454 HON

E454 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks March 16, 2005 citizens, namely African Americans, from inte- SOUTH PARK HIGH SCHOOL tors, William Reynolds and Elias Roberts, are grating into society after centuries of slavery, listed on the Monument among the victims of felon disenfranchisement laws prevent ex-of- HON. BRIAN HIGGINS the Wyoming Massacre. The first attempts to build a memorial date fenders from reintegrating into society after OF NEW YORK back to 1809. In the spring of 1841, the retribution. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Statistics on felon disenfranchisement indi- women of Luzeme County came together cate that Congressional action is clearly war- Tuesday, March 15, 2005 under the name Ladies Luzeme Monumental ranted. The Sentencing Project estimates that Mr. HIGGINS. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to Association and raised the money for the 4.7 million Americans, or 1 in 43 adults, have call your attention to the great South Park monument. In 1860, the State of Pennsylvania currently or permanently lost the right to vote High School in Buffalo, New York which this gave the title to the land to the Wyoming as a result of a felony conviction. 1.4 million year is celebrating 90 years of excellence in Monument Association. or 13 percent of African American men are educating Western New York’s young people. I was pleased to work with Betty in getting disenfranchised, a rate seven times the na- Ninety-one years ago this week, on St. Pat- the Wyoming Monument rightfully listed on the tional average. Given current rates of incarcer- rick’s Day, the people of South Buffalo broke National Register of Historic Places. -

William C. Velásquez Institute

William C. Velásquez Institute MEMORANDUM TO: Antonio Gonzalez, President, William C. Velasquez Institute, Concerned Parties FROM: Steven Ochoa, Director of Voting Rights Policy and Research, William C. Velasquez Institute DATE: July 10, 2007 Re: Analysis of Texas State House of Representative District Recent Registration Patterns and Targeted Potential Latino Influence Districts INTRODUCTION In the attached table and maps, you will find a general analysis of Texas House of Representative Districts. I did a comparison of the most detailed registration and turnout information, which dates from the November 2000 General Election to the 2006 November General Election. This data comes from the Texas Legislative Council. I included turnout information as well. Aside from growth and comparison figures, there is an attempt to measure potential Latino influence districts. A Latino influence district is described as having a Latino registration percentage between 25%-50%. A defined potential Latino influence district is defined by adding 10,000 Latino registered voters (and therefore adding 10,000 voters to the total registration) and determining what would be the district’s Latino registration percentage. If the potential Latino registration fell between 25%-50%, then the district was classified as a possible Latino influence district. GENERAL FINDINGS In the 6 years between 2000 and 2006, Texas gained 639,553 registered voters and 342,474 Latino registered voters. Latinos represented 53.55% of the Texas registration growth. Latinos outpaced total registration growth 17.10% to 6.23%. If Latinos are removed from the total registration, one notices that Latinos grew 17.10% in 6 years compared to non-Latinos growing 3.59%. -

Pensions & Investments

HOUSE COMMITTEE ON PENSIONS & INVESTMENTS TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES INTERIM REPORT 2004 A REPORT TO THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 79TH TEXAS LEGISLATURE REP. ALLAN RITTER CHAIRMAN COMMITTEE CLERK SHERRI WALKER Committee On Pensions & Investments November 24, 2004 Rep. Allan Ritter P.O. Box 2910 Chairman Austin, Texas 78768-2910 The Honorable Tom Craddick Speaker, Texas House of Representatives Members of the Texas House of Representatives Texas State Capitol, Rm. 2W.13 Austin, Texas 78701 Dear Mr. Speaker and Fellow Members: The Committee on Pensions & Investments of the Seventy-Eighth Legislature hereby submits its interim report including recommendations and drafted legislation for consideration by the Seventy-ninth Legislature. Respectfully submitted, _______________________ Rep. Allan Ritter _______________________ _______________________ Rep. Barry Telford Rep. Kent Grusendorf _______________________ _______________________ Rep. Patrick Rose Rep. Trey Martinez-Fischer _______________________ _______________________ Rep. Aaron Pena Rep. Ruth McClendon Rep. Kent Grusendorf Vice-Chairman Members: Rep. Barry Telford, Rep Patrick Rose, Rep. Trey Martinez-Fischer, Rep. Aaron Pena, Rep. Ruth McClendon TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 4 INTERIM STUDY CHARGES AND SUBCOMMITTEE ASSIGNMENTS............................... 5 PENSION OBLIGATION BONDS............................................................................................... -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

Case 1:11-cv-01303-RMC-TBG-BAH Document 230 Filed 08/28/12 Page 1 of 154 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) STATE OF TEXAS, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 11-1303 ) (TBG-RMC-BAH) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) and ERIC H. HOLDER, in his ) official capacity as Attorney General ) of the United States ) ) Defendants, and ) ) Wendy Davis, et. al., ) ) Intervenor-Defendants. ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION Before: GRIFFITH, Circuit Judge, COLLYER and HOWELL, District Judges. Opinion for the Court filed by Circuit Judge GRIFFITH, in which District Judge HOWELL joins and District Judge COLLYER joins all except section III.A.3. Separate opinion for the Court with respect to retrogression in Congressional District 25 filed by District Judge HOWELL, in which District Judge COLLYER joins. Dissenting opinion with respect to retrogression in Congressional District 25 filed by Circuit Judge GRIFFITH. Appendix filed by District Judges COLLYER and HOWELL, in which Circuit Judge GRIFFITH joins. Case 1:11-cv-01303-RMC-TBG-BAH Document 230 Filed 08/28/12 Page 2 of 154 Opinion for the Court by GRIFFITH, Circuit Judge: Table of Contents I. Background.............................................................................................................................. 3 II. Principles of Section 5 Analysis ............................................................................................. 5 A. Retrogression ....................................................................................................................