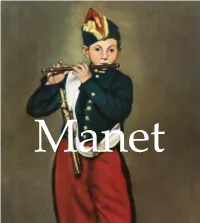

Édouard Manet (1832- 1883)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitchell Final4print.Pdf

VICTORIAN CRITICAL INTERVENTIONS Donald E. Hall, Series Editor VICTORIAN LESSONS IN EMPATHY AND DIFFERENCE Rebecca N. Mitchell THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Columbus Copyright © 2011 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mitchell, Rebecca N. (Rebecca Nicole), 1976– Victorian lessons in empathy and difference / Rebecca N. Mitchell. p. cm. — (Victorian critical interventions) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1162-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1162-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9261-7 (cd) 1. English literature—19th century—History and criticism. 2. Art, English—19th century. 3. Other (Philosophy) in literature. 4. Other (Philosophy) in art. 5. Dickens, Charles, 1812–1870— Criticism and interpretation. 6. Eliot, George, 1819–1880—Criticism and interpretation. 7. Hardy, Thomas, 1840–1928—Criticism and interpretation. 8. Whistler, James McNeill, 1834– 1903—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series: Victorian critical interventions. PR468.O76M58 2011 820.9’008—dc22 2011010005 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1162-5) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9261-7) Cover design by Janna Thompson Chordas Type set in Adobe Palatino Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materi- als. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS List of Illustrations • vii Preface • ix Acknowledgments • xiii Introduction Alterity and the Limits of Realism • 1 Chapter 1 Mysteries of Dickensian Literacies • 27 Chapter 2 Sawing Hard Stones: Reading Others in George Eliot’s Fiction • 49 Chapter 3 Thomas Hardy’s Narrative Control • 70 Chapter 4 Learning to See: Whister's Visual Averstions • 88 Conclusion Hidden Lives and Unvisited Tombs • 113 Notes • 117 Bibliography • 137 Index • 145 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1 James McNeill Whistler, The Miser (1861). -

H-France Review Vol. 12 (November 2012), No. 158 Therese Dolan, Ed., Perspectives On

H-France Review Volume 12 (2012) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 12 (November 2012), No. 158 Therese Dolan, ed., Perspectives on Manet. Surrey, U.K. and Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2012. xiii +230 pp. Illustrations, bibliography and index. $119.95 U.S. (cl). ISBN 978-1- 4094-2074-3. Review by Hollis Clayson, Northwestern University. A collection of essays on the work of the French and thoroughly Parisian artist, Édouard Manet (1832- 1883), has a built-in significance for art history that is somewhat concealed, even belied, by the unassuming “perspectives on” title of, and the neutral cast of the introduction to, Therese Dolan’s splendid anthology of nine new texts.[1] The interpretive stakes are high ipso facto because the history of modern art is rooted in Manet studies. As the influential scholar, Michael Fried, put it: “Manet is by common agreement the pivotal figure in the modern history of painting.”[2] Thus museum exhibitions of his art attract crowds as well as passionate scrutiny and debate, and pacesetting monographic studies are thick on the ground, appearing with increasing frequency since the centenary of the artist’s death.[3] Once upon a time not long ago (the 1980s), the axis of methodological range in Manet studies extended from radical formalism, at one end, to Marxist- and feminist-inflected social art history at the opposite pole. The history of that antipathy is too complex to delve into in an abbreviated review. Suffice it to note that that spectrum and its antitheses are not the principal hermeneutic frameworks of the scholarship gathered in the new anthology. -

L-G-0000349593-0002314995.Pdf

Manet Page 4: Self-Portrait with a Palette, 1879. Oil on canvas, 83 x 67 cm, Mr et Mrs John L. Loeb collection, New York. Designed by: Baseline Co Ltd 127-129A Nguyen Hue, Floor 3, District 1, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam © Sirrocco, London, UK (English version) © Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyrights on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case we would appreciate notification ISBN 978-1-78042-029-5 2 “He was greater than we thought he was.” — Edgar Degas 3 Biography 1832: Born Edouard Manet 23 January in Paris, France. His father is Director of the Ministry of Justice. Edouard receives a good education. 1844: Enrols into Rollin College where he meets Antonin Proust who will remain his friend throughout his life. 1848: After having refused to follow his family’s wishes of becoming a lawyer, Manet attempts twice, but to no avail, to enrol into Naval School. He boards a training ship in order to travel to Brazil. 1849: Stays in Rio de Janeiro for two years before returning to Paris. 1850: Returns to the School of Fine Arts. He enters the studio of artist Thomas Couture and makes a number of copies of the master works in the Louvre. 1852: His son Léon is born. He does not marry the mother, Suzanne Leenhoff, a piano teacher from Holland, until 1863. -

Manet the Modern Master

Manet the Modern Master ‘Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus’ Edouard Manet (1832-1883) oil on canvas, 111 x 70 cm Painted in 1868, the subject of the portrait is Fanny Claus, a close friend of Manet’s wife Suzanne Leenhoff. It was a preparatory study for ‘Le Balcon’ which now hangs in Musée d’Orsay. Originally the canvas was much larger, but Manet cut it up so that Berthe Morisot appears truncated on the right. He kept the painting in his studio during his lifetime. The artist John Singer Sargent then bought it at the studio sale following the artist’s death in 1884 and brought it to England. It stayed in the family until 2012 when it was put up for sale and The Ashmolean launched a successful fundraising campaign to save the painting from leaving the country. © Ashmolean Museum A modern portrait? Use of family and friends as models Manet’s ‘Portrait of Mlle Claus’ has an Manet broke new ground by defying traditional enigmatic quality that makes it very modern. techniques of representation and by choosing The remote and disengaged look on Fanny’s subjects from the events and circumstances face suggests a sense of isolation in urban of his own time. He also wanted to make society. The painting tells no story and its very a commentary on contemporary life and lack of narrative invites the viewer to construct frequently used family and friends to role play their own interpretations. It is a painting that has everyday (genre) scenes in his paintings. the ability to speak to us across the years. -

Page 70 H-France Review Vol. 3 (March 2003), No. 18 Carol

H-France Review Volume 3 (2003) Page 70 H-France Review Vol. 3 (March 2003), No. 18 Carol Armstrong, Manet Manette. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002. xviii, 400 pp. Figures, notes, and index. $50 U.S. (hb). ISBN 0-300-09658-5. Review by James Smalls, University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Just when you thought that everything has been said about the creative magnificence of Edouard Manet, a book such as Manet Manette by Carol Armstrong appears and provides a fresh approach and outlook. This hefty volume of 315 pages of text, in addition to sixty-three pages of explanatory endnotes, is intelligently illustrated and rich in art-historical and critical detail. Armstrong has not only harnessed and unpacked a great deal of information on Manet and his unique brand of modernism but also has done so with the art of many of his contemporaries. The book is ambitious in scope and divided into three interrelated parts, each of which has a successful outcome. Armstrong opens her text with a discussion of, what Clement Greenberg described as Manet’s “inconsistency,” that is, his sustained tendency not to paint in “connected series but in large ambitious singles.” This "inconsistency," according to Greenberg, is what sets him apart from other modernists who came before and after him (p. xvii) and was the significant aspect of his status as a unique modern artist. The first section of Armstrong’s book sets out to measure Manet’s “inconsistency” through the politics and poetics of his exhibition strategies. For the most part, Armstrong agrees with Greenberg and considers the “inconsistency,” “undecidability,” “irreducibility,” and the non-unified aspects of Manet’s brand of modernism as what makes him unique among his contemporaries. -

Issue Print Test | Nonsite.Org

ISSUE #14: NINETEENTH- CENTURY FRANCE NOW 14 nonsite.org is an online, open access, peer-reviewed quarterly journal of scholarship in the arts and humanities affiliated with Emory College of Arts and Sciences. 2015 all rights reserved. ISSN 2164-1668 1 EDITORIAL BOARD Bridget Alsdorf Ruth Leys James Welling Jennifer Ashton Walter Benn Michaels Todd Cronan Charles Palermo Lisa Chinn, editorial assistant Rachael DeLue Robert Pippin Michael Fried Adolph Reed, Jr. Oren Izenberg Victoria H.F. Scott Brian Kane Kenneth Warren FOR AUTHORS ARTICLES: SUBMISSION PROCEDURE Please direct all Letters to the Editors, Comments on Articles and Posts, Questions about Submissions to [email protected]. Potential contributors should send submissions electronically via nonsite.submishmash.com/Submit. Applicants for the B-Side Modernism/Danowski Library Fellowship should consult the full proposal guidelines before submitting their applications directly to the nonsite.org submission manager. Please include a title page with the author’s name, title and current affiliation, plus an up-to-date e-mail address to which edited text and correspondence will be sent. Please also provide an abstract of 100-150 words and up to five keywords or tags for searching online (preferably not words already used in the title). Please do not submit a manuscript that is under consideration elsewhere. ARTICLES: MANUSCRIPT FORMAT Accepted essays should be submitted as Microsoft Word documents (either .doc or .rtf), although .pdf documents are acceptable for initial submissions.. Double-space manuscripts throughout; include page numbers and one-inch margins. All notes should be formatted as endnotes. Style and format should be consistent with The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. -

Edouard Manet

Edouard Manet Edouard Manet (mah-NAY) 1832-1883 French Painter Edouard Manet was a transitional figure in 19th Vocabulary century French painting. He bridged the classical tradition of Realism and the new style of Impressionism—A style of art that originated in Impressionism in the mid-1800s. He was greatly 19th century France, which concentrated on influenced by Spanish painting, especially changes in light and color. Artists painted Velazquez and Goya. In later years, influences outdoors (en plein air) and used dabs of pure from Japanese art and photography also affected color (no black) to capture their “impression” of his compositions. Manet influenced, and was scenes. influenced by, the Impressionists. Many considered him the leader of this avant-garde Realism—A style of art that shows objects or group of artists, although he never painted a truly scenes accurately and objectively, without Impressionist work and personally rejected the idealization. Realism was also an art movement in label. 19th century France that rebelled against traditional subjects in favor of scenes of modern Manet was a pioneer in depicting modern life by life. generating interest in this new subject matter. He borrowed a lighter palette and freer brushwork Still life—A painting or drawing of inanimate from the Impressionists, especially Berthe Morisot objects. and Claude Monet. However, unlike the Impressionists, he did not abandon the use of black in his painting and he continued to paint in his studio. He refused to show his work in the Art Elements Impressionist exhibitions, instead preferring the traditional Salon. Manet used strong contrasts and Color—Color has three properties: hue, which is bold colors. -

Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet's Olympia to Matisse

Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet’s Olympia to Matisse, Bearden and Beyond Denise M. Murrell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2013 Denise M. Murrell All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet’s Olympia to Matisse, Bearden and Beyond Denise M. Murrell During the 1860s in Paris, Edouard Manet and his circle transformed the style and content of art to reflect an emerging modernity in the social, political and economic life of the city. Manet’s Olympia (1863) was foundational to the new manner of painting that captured the changing realities of modern life in Paris. One readily observable development of the period was the emergence of a small but highly visible population of free blacks in the city, just fifteen years after the second and final French abolition of territorial slavery in 1848. The discourse around Olympia has centered almost exclusively on one of the two figures depicted: the eponymous prostitute whose portrayal constitutes a radical revision of conventional images of the courtesan. This dissertation will attempt to provide a sustained art-historical treatment of the second figure, the prostitute’s black maid, posed by a model whose name, as recorded by Manet, was Laure. It will first seek to establish that the maid figure of Olympia, in the context of precedent and Manet’s other images of Laure, can be seen as a focal point of interest, and as a representation of the complex racial dimension of modern life in post-abolition Paris. -

T T-\Yf-T Dissertation U I V L L Information Service University Microfilms Intemational a Bell & Howell Information Company 300 N

INFORMATiOîi TO USERS This reproduction was made from .1 copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced te.:hnology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, tfje quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages in any manuscript may have indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been Aimed. The following explariation of techniques is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When it is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to indicate this. 3. Oversize materials (maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sec tioning the original, beginning at the upper left hand comer and continu ing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. E%ach oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or in black and white paper format. • 4. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or micro- Oche but lack clarity on xerographic copies made from the microAlm. Fbr an additional charge, all photographs are available in black and white standard 35mm slide format.* «For more information about black and white slides or enlarged paper reproductions, please contact the Dissertatlona Customer Services Department. T T-\yf-T Dissertation U i V l l Information Service University Microfilms Intemational A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 N. -

Naked People

© COPYRIGHT by Carmen D. Cain 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED NAKED PEOPLE BY Carmen D. Cain ABSTRACT Naked People is an original work of fiction. This collection of stories follows the main protagonist from adolescence to young adulthood where she decides at various points whether or not to fit in with her peers. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. iii GRANNY SQUARES ........................................................................................................ 1 FRIENDSHIP BRACELETS............................................................................................ 13 HEARTS ........................................................................................................................... 28 NAKED PEOPLE ............................................................................................................. 47 RAMBLES ........................................................................................................................ 67 SHARED HOUSING........................................................................................................ 84 iii GRANNY SQUARES Grandma Margaret cooked outrageous amounts of food for dinner: chicken or ham and once even a turkey with mashed potatoes and cranberry sauce, although it was July. For lunch she set out a bag of bread, a selection -

Manet's Contemporaries

MANET’S ‘COUP DE TÊTE’: THE SECRETS HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT O COUP DE TÊTE DE MANET: OS SEGREDOS ’: The Secrets Hidden in Plain Sight ESCONDIDOS EM PLENA LUZ DO DIA Coup de Tête Manet’s ‘ Manet’s Moyra Anne Ashford EL COUP DE TÊTE DE MANET: LOS SECRETOS ESCONDIDOS A MOYRA ANNE ASHFORD PLENA LUZ DEL DÍA ARS - N 40 ANO 18 126 ABSTRACT Modern art began with Édouard Manet’s The Picnic (Le Déjeuner sur L’Herbe, 1863). A small minority of scholars have ventured that Manet’s impetus for breaking from Artigo Inédito Moyra Anne Ashford* tradition stemmed from memories of his 1849 voyage to Brazil. This view is eschewed by the majority and the museum establishment, who hold to a French and classical origin. * Essayist and former journalist at The Sunday Through a close examination of early written sources, the paintings themselves and Times and The Daily Telegraph, United links to 19th century Rio, the author proposes that Manet worked distinct Rio memories Kingdom. DOI: 10.11606/issn.2178- into two pivotal paintings: The Picnic, which he set in the forests of Guanabara Bay; 0447.ars.2020.176216 Olympia (1863) was inspired not by a Parisian brothel, but by slave-owning, mid- nineteenth century Rio de Janeiro. This article recounts how the research unfolded. KEYWORDS Édouard Manet; Rio de Janeiro; Émile Zola; Olympia; Impressionism ’: The Secrets Hidden in Plain Sight RESUMO RESUMEN A arte moderna teve início com Le Déjeuner sur L’Herbe (1863), El arte moderno empezó con Le Déjeuner sur L’Herbe de Édouard Manet. -

A Comparative Study of Suzanne Valadon and William Bouguereau Mary Sheehy Coastal Carolina University

Coastal Carolina University CCU Digital Commons Honors College and Center for Interdisciplinary Honors Theses Studies Fall 12-15-2012 Challenging the Ideal: A Comparative Study of Suzanne Valadon and William Bouguereau Mary Sheehy Coastal Carolina University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/honors-theses Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Sheehy, Mary, "Challenging the Ideal: A Comparative Study of Suzanne Valadon and William Bouguereau" (2012). Honors Theses. 64. https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/honors-theses/64 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College and Center for Interdisciplinary Studies at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Introduction The female nude has been represented in art for millennia. From the Paleolithic Woman of Willendorf fertility symbol (22,000 to 24,000 BCE, Fig. 1), to Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538 Fig. 2), women have frequently been depicted as sexualized creatures. Standard ideal body types have been established for each era through the thousands of pieces of art picturing nude women. Archaic women were expected to have large breasts and hips in order to show their fertility. Medieval representations of Mary Magdalene were usually nude and provocative. Women were supposed to see these images of Mary Magdalene and remember to keep their chastity. Women in the Renaissance were thought to be beautiful if they were fleshy, soft, and curvy, like Titian’s Venus of Urbino.