Wrestling with the Prince of Persia: a Study on Daniel 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Most Common Jewish First Names in Israel Edwin D

Names 39.2 (June 1991) Most Common Jewish First Names in Israel Edwin D. Lawson1 Abstract Samples of men's and women's names drawn from English language editions of Israeli telephone directories identify the most common names in current usage. These names, categorized into Biblical, Traditional, Modern Hebrew, and Non-Hebrew groups, indicate that for both men and women over 90 percent come from Hebrew, with the Bible accounting for over 70 percent of the male names and about 40 percent of the female. Pronunciation, meaning, and Bible citation (where appropriate) are given for each name. ***** The State of Israel represents a tremendous opportunity for names research. Immigrants from traditions and cultures as diverse as those of Yemen, India, Russia, and the United States have added their onomastic contributions to the already existing Jewish culture. The observer accustomed to familiar first names of American Jews is initially puzzled by the first names of Israelis. Some of them appear to be biblical, albeit strangely spelled; others appear very different. What are these names and what are their origins? Benzion Kaganoffhas given part of the answer (1-85). He describes the evolution of modern Jewish naming practices and has dealt specifi- cally with the change of names of Israeli immigrants. Many, perhaps most, of the Jews who went to Israel changed or modified either personal or family name or both as part of the formation of a new identity. However, not all immigrants changed their names. Names such as David, Michael, or Jacob required no change since they were already Hebrew names. -

Angelology Angelology

Christian Angelology Angelology Introduction Why study Angels? They teach us about God As part of God’s creation, to study them is to study why God created the way he did. In looking at angels we can see God’s designs for his creation, which tells us something about God himself. They teach us about ourselves We share many similar qualities to the angels. We also have several differences due to them being spiritual beings. In looking at these similarities and differences we can learn more about the ways God created humanity. In looking at angels we can avoid “angelic fallacies” which attempt to turn men into angels. They are fascinating! Humans tend to be drawn to the supernatural. Spiritual beings such as angels hit something inside of us that desires to “return to Eden” in the sense of wanting to reconnect ourselves to the spiritual world. They are different, and different is interesting to us. Fr. J. Wesley Evans 1 Christian Angelology Angels in the Christian Worldview Traditional Societies/World of the Bible Post-Enlightenment Worldview Higher Reality God, gods, ultimate forces like karma and God (sometimes a “blind watchmaker”) fate [Religion - Private] Middle World Lesser spirits (Angels/Demons), [none] demigods, magic Earthly Reality Human social order and community, the Humanity, Animals, Birds, Plants, as natural world as a relational concept of individuals and as technical animals, plants, ect. classifications [Science - Public] -Adapted from Heibert, “The Flaw of the Excluded Middle” Existence of Angels Revelation: God has revealed their creation to us in scripture. Experience: People from across cultures and specifically Christians, have attested to the reality of spirits both good and bad. -

The Prince of Persia Returns

THE PRINCE OF PERSIA RETURNS ACTION-PACKED PRINCE OF PERSIA ® 2 (WORKING TITLE) BOASTS BRAND NEW FREE-FORM FIGHTING SYSTEM Paris, FRANCE - May 6, 2004 - Ubisoft, one of the world's largest video game publishers, today announced that the company‘s award-winning Montreal studio is currently developing Prince of Persia ® 2 (working title) , a follow-up to the most critically acclaimed game of 2003, Prince of Persia The Sands of Time™. The Prince has to embark upon a path of both carnage and mystery to defy his preordained death. His journey leads to the infernal core of a cursed island stronghold harboring mankind‘s greatest fears. Only through grim resolve, bitter defiance and the mastery of deadly new combat arts can the Prince rise to a new level of warriorship œ and emerge from this ultimate trial with his life. In order to accomplish his mission, the Prince benefits from a brand new free- form fighting system that allows gamers to channel his anger as they wage battle without boundaries. Each game fan will find his or her own unique fighting style as they manipulate their environment and control the Ravages of Time. You can dig into an arsenal of weapons that, when used in combination, create advanced arm attacks that verge on fatal artistry! Prince of Persia ® 2 promises that game fans will fight harder, and play longer, emerging from the experience as deadly-capable skilled masters of their own unique combat art form. —Prince of Persia The Sands of Time™ was the most critically acclaimed game of 2003,“ said Yves Guillemot, President and CEO of Ubisoft, —With Prince of Persia ® 2 , we intend to build on that masterpiece that will take Prince of Persia ® one step further to take over the action-combat genre. -

Inmate Release Report Snapshot Taken: 9/28/2021 6:00:10 AM

Inmate Release Report Snapshot taken: 9/28/2021 6:00:10 AM Projected Release Date Booking No Last Name First Name 9/29/2021 6090989 ALMEDA JONATHAN 9/29/2021 6249749 CAMACHO VICTOR 9/29/2021 6224278 HARTE GREGORY 9/29/2021 6251673 PILOTIN MANUEL 9/29/2021 6185574 PURYEAR KORY 9/29/2021 6142736 REYES GERARDO 9/30/2021 5880910 ADAMS YOLANDA 9/30/2021 6250719 AREVALO JOSE 9/30/2021 6226836 CALDERON ISAIAH 9/30/2021 6059780 ESTRADA CHRISTOPHER 9/30/2021 6128887 GONZALEZ JUAN 9/30/2021 6086264 OROZCO FRANCISCO 9/30/2021 6243426 TOBIAS BENJAMIN 10/1/2021 6211938 ALAS CHRISTOPHER 10/1/2021 6085586 ALVARADO BRYANT 10/1/2021 6164249 CASTILLO LUIS 10/1/2021 6254189 CASTRO JAYCEE 10/1/2021 6221163 CUBIAS ERICK 10/1/2021 6245513 MYERS ALBERT 10/1/2021 6084670 ORTIZ MATTHEW 10/1/2021 6085145 SANCHEZ ARAFAT 10/1/2021 6241199 SANCHEZ JORGE 10/1/2021 6085431 TORRES MANLIO 10/2/2021 6250453 ALVAREZ JOHNNY 10/2/2021 6241709 ESTRADA JOSE 10/2/2021 6242141 HUFF ADAM 10/2/2021 6254134 MEJIA GERSON 10/2/2021 6242125 ROBLES GUSTAVO 10/2/2021 6250718 RODRIGUEZ RAFAEL 10/2/2021 6225488 SANCHEZ NARCISO 10/2/2021 6248409 SOLIS PAUL 10/2/2021 6218628 VALDEZ EDDIE 10/2/2021 6159119 VERNON JIMMY 10/3/2021 6212939 ADAMS LANCE 10/3/2021 6239546 BELL JACKSON 10/3/2021 6222552 BRIDGES DAVID 10/3/2021 6245307 CERVANTES FRANCISCO 10/3/2021 6252321 FARAMAZOV ARTUR 10/3/2021 6251594 GOLDEN DAMON 10/3/2021 6242465 GOSSETT KAMERA 10/3/2021 6237998 MOLINA ANTONIO 10/3/2021 6028640 MORALES CHRISTOPHER 10/3/2021 6088136 ROBINSON MARK 10/3/2021 6033818 ROJO CHRISTOPHER 10/3/2021 -

Dr. Hanchen Huang's CV

Hanchen Huang Dean of Engineering & Lupe Murchison Foundation Chair Professor, UNT ([email protected]) Co-founder, MesoGlue Inc. ([email protected]); Cell phone: 860-771-0771 A. Scholarship ................................................................................................................................. 2 A.1 Science and Technology of Metallic Nanorods .................................................................... 2 A.2 Other Disciplines .................................................................................................................. 3 B. Leadership in Academia ............................................................................................................. 3 B.1 Leadership on University Campuses .................................................................................... 4 B.2 Leadership in Professional Societies .................................................................................... 4 C. Bio-sketch ................................................................................................................................... 5 D. Honors, Awards, and Recognitions ............................................................................................ 5 E. Work Experiences ....................................................................................................................... 6 F. Educational Background ............................................................................................................. 8 G. Research Grants ......................................................................................................................... -

Our Lady of the Assumption Parish 545 Stratfield Road Fairfield, CT 06825-1872 Tel

Our Lady of the Assumption Parish 545 Stratfield Road Fairfield, CT 06825-1872 Tel. (203) 333-9065 Fax: (203) 333-2562 Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.olaffld.org “Ad Jesum per Mariam” To Jesus through Mary. Clergy/Lay Leadership Rev. Peter A. Cipriani, Pastor Rev. Michael Flynn, Parochial Vicar Deacon Raymond John Chervenak Deacon Robert McLaughlin Michael Cooney, Director of Music Daniel Ford, Esq., Trustee Masses (Schedules subject to change) Saturday Vigil Mass: 4 PM Sunday Masses: 7:30 AM, 9 AM 10:30 AM and 12:00 PM (Subject to change) Morning Daily Mass: (Mon.-Sat.) 7:30 AM Evening Daily Mass: (Mon.-Fri.) 5:30 PM Holy Days: See Bulletin for schedule Sacrament of Reconciliation Saturday: 1:30– 2:30 PM or by appointment. Every Tuesday: 7-8:00 PM Rosary/Divine Mercy Chaplet 7 AM Monday-Saturday, Rosary 8 AM First Saturday of each month, Rosary 3 PM Monday-Friday, Divine Mercy Chaplet and Rosary Rite of Christian Initiation for Adults (RCIA) Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament Anyone interested in becoming a Roman Catholic becomes a part of this First Friday of each month from 8 AM process, as can any adult Catholic who has not received all the Sacraments of Friday to 7:15 AM Saturday. To volunteer initiation. For further information contact the Faith Formation office. contact Grand Knight, Michael Lauzon at (203) 817-7528. Sacrament of Baptism This Sacrament is celebrated on Sundays at 1:00 PM. It is required that Novenas parents participate in a Pre-Baptismal class. Classes are held on the third Miraculous Medal-8 AM. -

Ubisoft Studios

CREATIVITY AT THE CORE UBISOFT STUDIOS With the second largest in-house development staff in the world, Ubisoft employs around 8 000 team members dedicated to video games development in 29 studios around the world. Ubisoft attracts the best and brightest from all continents because talent, creativity & innovation are at its core. UBISOFT WORLDWIDE STUDIOS OPENING/ACQUISITION TIMELINE Ubisoft Paris, France – Opened in 1992 Ubisoft Bucharest, Romania – Opened in 1992 Ubisoft Montpellier, France – Opened in 1994 Ubisoft Annecy, France – Opened in 1996 Ubisoft Shanghai, China – Opened in 1996 Ubisoft Montreal, Canada – Opened in 1997 Ubisoft Barcelona, Spain – Opened in 1998 Ubisoft Milan, Italy – Opened in 1998 Red Storm Entertainment, NC, USA – Acquired in 2000 Blue Byte, Germany – Acquired in 2001 Ubisoft Quebec, Canada – Opened in 2005 Ubisoft Sofia, Bulgaria – Opened in 2006 Reflections, United Kingdom – Acquired in 2006 Ubisoft Osaka, Japan – Acquired in 2008 Ubisoft Chengdu, China – Opened in 2008 Ubisoft Singapore – Opened in 2008 Ubisoft Pune, India – Acquired in 2008 Ubisoft Kiev, Ukraine – Opened in 2008 Massive, Sweden – Acquired in 2008 Ubisoft Toronto, Canada – Opened in 2009 Nadeo, France – Acquired in 2009 Ubisoft San Francisco, USA – Opened in 2009 Owlient, France – Acquired in 2011 RedLynx, Finland – Acquired in 2011 Ubisoft Abu Dhabi, U.A.E – Opened in 2011 Future Games of London, UK – Acquired in 2013 Ubisoft Halifax, Canada – Acquired in 2015 Ivory Tower, France – Acquired in 2015 Ubisoft Philippines – Opened in 2016 UBISOFT PaRIS Established in 1992, Ubisoft’s pioneer in-house studio is responsible for the creation of some of the most iconic Ubisoft brands such as the blockbuster franchise Rayman® as well as the worldwide Just Dance® phenomenon that has sold over 55 million copies. -

Disruptive Innovation and Internationalization Strategies: the Case of the Videogame Industry Par Shoma Patnaik

HEC MONTRÉAL Disruptive Innovation and Internationalization Strategies: The Case of the Videogame Industry par Shoma Patnaik Sciences de la gestion (Option International Business) Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de maîtrise ès sciences en gestion (M. Sc.) Décembre 2017 © Shoma Patnaik, 2017 Résumé Ce mémoire a pour objectif une analyse des deux tendances très pertinentes dans le milieu du commerce d'aujourd'hui – l'innovation de rupture et l'internationalisation. L'innovation de rupture (en anglais, « disruptive innovation ») est particulièrement devenue un mot à la mode. Cependant, cela n'est pas assez étudié dans la recherche académique, surtout dans le contexte des affaires internationales. De plus, la théorie de l'innovation de rupture est fréquemment incomprise et mal-appliquée. Ce mémoire vise donc à combler ces lacunes, non seulement en examinant en détail la théorie de l'innovation de rupture, ses antécédents théoriques et ses liens avec l'internationalisation, mais en outre, en situant l'étude dans l'industrie des jeux vidéo, il découvre de nouvelles tendances industrielles et pratiques en examinant le mouvement ascendant des jeux mobiles et jeux en lignes. Le mémoire commence par un dessein des liens entre l'innovation de rupture et l'internationalisation, sur le fondement que la recherche de nouveaux débouchés est un élément critique dans la théorie de l'innovation de rupture. En formulant des propositions tirées de la littérature académique, je postule que les entreprises « disruptives » auront une vitesse d'internationalisation plus élevée que celle des entreprises traditionnelles. De plus, elles auront plus de facilité à franchir l'obstacle de la distance entre des marchés et pénétreront dans des domaines inconnus et inexploités. -

Ubisoft Unveils It's New Growth Plan for Québec

Ubisoft Expands its Quebec Operations • Plans 1000 New Jobs by 2013 • Opens a Studio Specialized in the Creation of Digital Cinema Content City, Country, February 9, 2007 – Ubisoft, one of the world’s largest video game publishers, announces today a new phase of development for its operations in Quebec, Canada. The company, which currently boasts more than 1,600 team members in the province, could invest up to an additional 295.6 million euros1 over the next six years with the goal of building up a team of 3,000 employees by 2013. This forecast exceeds current development objectives for 2005-2010 by an additional 1,000 jobs. To encourage the successful implementation of this third phase of the group’s expansion in the province, both the Quebec and Canadian governments will continue to strongly support Ubisoft. The plan for the creation of 1,000 new jobs revolves around two main objectives: • Firstly, the group has set a goal of creating 500 new video game positions in Quebec by 2013. • Secondly, Ubisoft will inaugurate a new production center, specialized in the creation of digital cinema content, i.e. computer generated images (CGI). The studio’s mission will be to produce short films whose inspiration is drawn from games based on Ubisoft brands. A first eight-minute short film will be based on the award-winning and highly anticipated game, Assassin’s Creed. By 2013, the new CGI studio should count 500 specialists. Today’s announcement was made by Mr. Yves Guillemot, Chief Executive Officer and Co- Founder of Ubisoft and Yannis Mallat, Chief Executive Officer of Ubisoft’s Montreal studio, in the presence of Mr. -

Ubisoft Announces Prince of Persia® Rival Swords for the Psp® System

UBISOFT ANNOUNCES PRINCE OF PERSIA® RIVAL SWORDS FOR THE PSP® SYSTEM The Prince of Persia Returns with New Multiplayer Feature Paris, FRANCE – SEPTEMBER 11, 2006 – Today Ubisoft, one of the world’s largest video game publishers, announced Prince of Persia® Rival Swords for the PSP® (PlayStation®Portable) system. Developed by Pipeworks Software, a division of Foundation 9 Entertainment, the game builds on last year’s console success’ Prince of Persia The Two Thrones™, and features original content such as additional levels and new multiplayer modes. The game is scheduled to ship for holiday 2006 in Europe and in 2007 in North America. In Prince of Persia Rival Swords, the Prince makes his way home to Babylon, bearing with him Kaileena, the enigmatic Empress of Time, and unspeakable scars from the Island of Time. But instead of the peace he longs for, he finds his kingdom ravaged by war and Kaileena the target of a brutal plot. When she is kidnapped, the Prince tracks her to the palace – only to see her murdered by a powerful enemy. Her death unleashes the Sands of Time, which strike the Prince and threaten to destroy everything he holds dear. Cast out on the streets, hunted as a fugitive, the Prince soon discovers that the Sands have tainted him, too. They have given rise to a deadly Dark Prince, whose spirit gradually possesses him. Key Features: • New multiplayer experience: Versus play in timed races as either the Prince or Dark Prince. Interrupt and impede your opponent’s progress by activating switches in your own level that will trigger traps and obstacles in their level. -

A Prophecy of the Christ!

A PROPHECY OF THE CHRIST! Gabriel’s Prophecy of the 70 Weeks (Daniel 9:24-27) Murray McLellan A Prophecy of the Christ! Gabriel’s Prophecy of the 70 Weeks (Daniel 9:24-27) Presented by Murray McLellan, an unworthy sinner upon whom grace unimaginable has been poured by the kindest of Kings. I do not claim to be, nor seek to be original in the following manuscript. I seek to magnify and exalt the Lord Jesus Christ, by whom the world has been crucifed to me, and I to the world. Unto him belong the glory and the dominion forever and ever. Amen. “Seventy weeks are determined for your people and for your holy city, To fnish the transgression, To make an end of sins, To make reconciliation for iniquity, To bring in everlasting righteousness, To seal up vision and prophecy, And to anoint the Most Holy. Know therefore and understand, that from the going forth of the command to restore and build Jerusalem until Messiah the Prince, there shall be seven weeks and sixty-two weeks; The street shall be built again, and the wall, even in troublesome times. And after the sixty-two weeks Messiah shall be cut off, but not for Himself; And the people of the prince who is to come shall destroy the city and the sanctuary. The end of it shall be with a food, and till the end of the war desolations are determined. Then he shall confrm a covenant with many for one week; but in the middle of the week He shall bring an end to sacrifce and offering. -

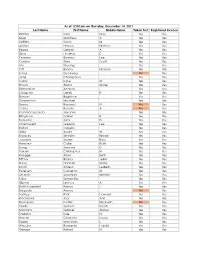

Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License

As of 12:00 am on Thursday, December 14, 2017 Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License Richter Sara May Yes Yes Silver Matthew A Yes Yes Griffiths Stacy M Yes Yes Archer Haylee Nichole Yes Yes Begay Delores A Yes Yes Gray Heather E Yes Yes Pearson Brianna Lee Yes Yes Conlon Tyler Scott Yes Yes Ma Shuang Yes Yes Ott Briana Nichole Yes Yes Liang Guopeng No Yes Jung Chang Gyo Yes Yes Carns Katie M Yes Yes Brooks Alana Marie Yes Yes Richardson Andrew Yes Yes Livingston Derek B Yes Yes Benson Brightstar Yes Yes Gowanlock Michael Yes Yes Denny Racheal N No Yes Crane Beverly A No Yes Paramo Saucedo Jovanny Yes Yes Bringham Darren R Yes Yes Torresdal Jack D Yes Yes Chenoweth Gregory Lee Yes Yes Bolton Isabella Yes Yes Miller Austin W Yes Yes Enriquez Jennifer Benise Yes Yes Jeplawy Joann Rose Yes Yes Harward Callie Ruth Yes Yes Saing Jasmine D Yes Yes Valasin Christopher N Yes Yes Roegge Alissa Beth Yes Yes Tiffany Briana Jekel Yes Yes Davis Hannah Marie Yes Yes Smith Amelia LesBeth Yes Yes Petersen Cameron M Yes Yes Chaplin Jeremiah Whittier Yes Yes Sabo Samantha Yes Yes Gipson Lindsey A Yes Yes Bath-Rosenfeld Robyn J Yes Yes Delgado Alonso No Yes Lackey Rick Howard Yes Yes Brockbank Taci Ann Yes Yes Thompson Kaitlyn Elizabeth No Yes Clarke Joshua Isaiah Yes Yes Montano Gabriel Alonzo Yes Yes England Kyle N Yes Yes Wiman Charlotte Louise Yes Yes Segay Marcinda L Yes Yes Wheeler Benjamin Harold Yes Yes George Robert N Yes Yes Wong Ann Jade Yes Yes Soder Adrienne B Yes Yes Bailey Lydia Noel Yes Yes Linner Tyler Dane Yes Yes